MRS. TREDICK'S HUSBAND

By Ralph D. Paine

Illustrations by W. J. Aylward

HE vastly admired his wife and was even more afraid of her. This, in a word, was the situation whenever Captain Charles Tredick came home from sea and briefly tarried between voyages in the neat white house on an upper reach of the Penobscot. He was a little man, shy and reticent, who had plodded up and down in the coastwise trade for years as master of schooners owned in Bath. They were old vessels, of no great size, but he sailed them on shares and managed to earn a modest profit even when freights were low.

At forty he had offered himself and his worldly goods to a blooming, vigorous spinster, somewhat younger, who was tired of teaching elocution in the endowed academy. She regarded the mariner as a proper husband because he was so seldom under foot. Contentedly she lived alone and dominated the Civic League and the Ladies' Aid of the highly organized village community.

A meeting of which she was chairman had detained her one autumn afternoon when Captain Tredick swung briskly into a quiet street from whose arching trees the last brown leaves had drifted. This vista was never bleak to him and he gazed in hope of seeing his wife, who was too busy, no doubt, to come to the station. Scrupulously well dressed, the clipped mustache just turning gray, he suggested rather the competent merchant than the veteran seafarer as he turned in at his own gate and set down the suitcase.

At finding the door locked he trudged around to the wood-shed, methodically raised the lid of the ice-box, and discovered a key with which he entered the kitchen and passed through into the front of the house. It was so immaculate and so lonely that he retreated like an intruder, lighting his pipe and strolling in the garden until he sighted the stately Mrs. Tredick in the offing. His bronzed face glowed with the ardor of youth as he kissed her cheek, homage which she graciously accepted as her due.

"Your telegram from Portland came at noon, Charles," said she, in her measured manner, "but an election of officers made it necessary"

"Of course; I understand, Sadie Marion," he interrupted, a little nervously. "A fine run from Norfolk, with a regular snoozer of a fair wind, brought us in two or three days earlier than I had reckoned."

"Isn't that nice! I must rest a few minutes while you tell me about it. You are looking so well, Charles."

"Why not? Just twiddled my thumbs and let the James K. Haskell jam her cargo of coal along. You are a very handsome woman, my dear, and growing more so. This being away from you makes me mighty unhappy."

This was an unusual display of feeling, but Sadie Marion ignored its tragic aspect, responding with a shade of criticism.

"But you cannot retire and live ashore. That is out of the question unless you can lay up money faster than this. With more push and ambition, Charles, would you be so resigned to remaining in a small four-master?"

This silenced him, and his wife relaxed to recover strength in a favorite chair. He had often tried to persuade her to live aboard the vessel with him, or at least make a voyage now and then, but her refusal was absolute. He followed a life apart, solitary, detached, of which she had not the slightest comprehension, in which she manifested no sympathetic interest. With a sigh he went into the kitchen and filled the wood-box, swept up the chips, and performed other routine tasks with habitual deftness.

At supper Sadie Marion, her mood refreshed, talked of her own engrossing affairs while he listened with reverent attention. Social aspirations disquieted her. She desired a house more pretentious, a hired girl, and had visions of driving her own runabout.

"I have done pretty well with the James K. Haskell," observed Captain Tredick, in mild extenuation; "better than the other skippers that had her. But she can't earn us a fortune, that's a fact. I own a sixteenth of her and I guess I can sell it to raise ready cash if you really need it."

"That is an investment, Charles, and I do not propose to spend our capital," she curtly replied. "You say the schooner is slow and leaky, and needs repairs so often that it seriously reduces her earnings. Have you honestly tried to find another position?"

"Owners know me and my reputation," was the patient answer. "They don't seem to tumble over themselves to snatch me out of the Haskell. So you are actually invited to read a paper at the woman's State convention, Sadie Marion! Well, I call it wonderful, and I am prouder of you than ever."

"I consider it my duty to grasp at opportunity," she roundly informed him, again the elocutionist. "My subject is to be 'The Problem of the Home.' I shall be writing until quite late this evening, Charles. If you will get breakfast"

"Certainly, Sadie Marion," he replied with a smile. "Eggs and toast and coffee? And I plan to tackle the wood-pile and rake up the yard while I'm home."

"Thank you. Please run over to the post-office before it closes. You will have to go right away."

He bolted a cup of tea, caught up his hat, and vanished at a trot, a zealous, unresentful errand-boy who expected no thanks. As a problem of the home he was the negligible factor. The post-master, greeting him warmly, hastened to add:

"Your 'phone is out of order, Cap'n Charles, tho' mebbe you don't know it yet, and central has been ringin' up the line off an' on since sundown. I was about to step over and tell you that Portland seems powerful anxious to get hold of you."

"Portland?" cried the shipmaster, instantly alert. "Something wrong aboard my vessel?"

"Better ask for a connection from here," advised the other.

Behind the partition Captain Tredick cocked his head and blinked incredulously when, at length, there came to his ear a resonant voice which announced itself to be that of Marvin Ellsworth, the patriarch of coastwise shipping, managing owner of the Ellsworth fleet of great schooners, the noblest sailing craft that survived to fly the Stars and Stripes. He was saying:

"Can't you hear me, Captain Tredick? Her master has quit to go in steam. Get that? The Fannie Ellsworth! Yes, she is here now, discharging. What's the matter? Repeat it? I want you to take her, customary wages and primage, five per cent of the gross freight. We can talk details if you will be in Portland to-morrow morning."

Captain Charles Tredick backed away from the instrument, still clutching the receiver, and mopped a dripping brow. He was breathing hard with excitement and needed a moment's respite. The Fannie Ellsworth, six-master, one of the finest of the fleet, stowing five thousand tons of coal beneath her hatches, the envy of a hundred skippers! Honestly believing himself unworthy of this singular distinction, he returned to the interview and unsteadily exclaimed:

"Are you sure it's me you have in mind, Mr. Ellsworth? Tredick of the James K. Haskell?"

"What kind of a fool do you think I am?" shouted the lord of sail. "I know all about you and your record for twenty years. Oh, damn the rotten old basket of a James K. Haskell! You are too conscientious. You won't be leaving her in the lurch. I fixed that up with your owners to-day. They are delighted to see you shove ahead and they've found a man to go in her. You accept? All right. At my office, nine o'clock sharp to-morrow. Good-night, Captain Tredick."

Disregarding the curious postmaster, he hurried into the darkness and halted to collect his thoughts. This would be great news for Sadie Marion, but his native caution warned him to withhold it until confirmed beyond a chance of doubt. Marvin Ellsworth was a tyrant with a sudden temper and there were matters to discuss. Already, however, it was like a revelation that he was a better man in the eyes of others than he had ever dreamed possible. It colored his feeling for Sadie Marion, who held him in such low esteem. When he entered the house with less timidity than usual, she spoke up.

"You knew I was waiting for the mail, Charles. Where have you been all this time?"

"I stopped to talk. I have friends who are glad to see me ashore," he answered. "There were no letters."

"Are you sure? Where is The Lewiston Journal?"

"By George, I clean forgot it, my dear. I am afraid Silas has shut up shop."

With an impatient gesture she turned to the desk in the sitting-room, while Charles tiptoed into the kitchen and washed the dishes. Later he sat by an open fire and meditatively sucked at an empty pipe, for smoking annoyed Sadie Marion. The bonds of his loving servitude chafed him and the sensation was so novel that it painfully absorbed his attention. He perceived a glimpse of the truth—that the most admirable of women, whose companionship he craved, had never tried to understand him.

At daylight next morning he stole down-stairs without awakening her and wrote this note:

"I have to catch the early train for Portland to look after some business. Very sorry about breakfast, but the fire is ready to light. Hope to be home again before sailing.

"Your loving

Charles

With an hour to spare when he reached the city, he steered for the coal wharf where the six topmasts of the Fannie Ellsworth soared skyward. A boyish elation made his heart beat faster as he climbed aboard and surveyed three hundred feet of deck that swept in a mighty sheer from bow to stern. All her proportions seemed colossal. Undismayed, however, he walked aft and encountered the first mate, a tall, deep-chested figure

of a sailor with a powerful voice. He was in the prime of middle age, ruddy and genial, and his smile suggested a tolerant amusement as he looked down at little Captain Tredick and exclaimed:

"Good morning! What can I do for you? The old man has gone ashore. Something from the office?"

The visitor stiffened and his chin went up as he crisply replied:

"Show me the ship, if you please. I expect to go as master. Your name?"

The mate stepped back, his rich complexion mottled with angry surprise, his disappointment betraying itself as he ejaculated:

"You take the Fannie Ellsworth? This is the first I've heard of it. I—I am Mr. Staunton."

"Figured on getting her yourself, did you, Mr. Staunton? Well, you guessed wrong. You can stay if you like. I'll try you out for a voyage, anyhow."

Slightly dazed, the mate gulped and rubbed his cheek while Captain Tredick entered the after-house. The cabin, with its mahogany finish and leather chairs, the cosey dining-room, the spare state-rooms, the tiled bath and steam heat, his own spacious sleeping-quarters and carved four-poster fairly dazzled his simple tastes and instantly appealed to him as a home afloat fitted for and worthy of his queenly Sadie Clarion. In a daydream he forgot the presence of the crestfallen mate and reluctantly went on deck to scrutinize the sails and rigging.

At nine o'clock old Marvin Ellsworth, rumpling his white beard and roaring at his clerks, clapped a hand on Captain Tredick's shoulder and rammed him into a chair, inquiring:

"Dodged aboard to look her over, did you? I saw you cross the street. Sure you can handle such a walloper of a schooner?"

"Yes, sir," quietly said the shipmaster, "but you will have to spend some money before she goes to sea—new canvas and running-gear."

"Humph! So that's your style," snorted the owner. "I am hiring you to make money in her. The other man found no fault."

"He let her run down, Mr. Ellsworth. Winter is coming on and I take no chances with worn-out stuff. Quick passages mean dividends, and I understand she hasn't been earning them."

"What if I tell you to go to the devil with your extravagant nonsense. Captain Tredick?"

"Then you can look for another skipper, sir," was the sharp retort.

"You'll do," boomed Marvin Ellsworth. "A bantam with spurs, hey? Just between us, coastwise freights will soon feel this European war. They're bound to jump, and you'll see two-dollar coal from Norfolk before Christmas. So go to it, and clean up six or seven hundred a month for yourself. Married, are you?"

"Yes, Mr. Ellsworth," pensively answered Charles. "I wish I could coax my wife to go with me. Any objection?"

"Not a bit. Now let's get things under way as fast as the Lord will let us. I have a charter-party waiting."

Anxious to supervise the work. Captain Tredick remained three days with his vessel before he was satisfied to return to Sadie Marion. He wrote, but reserved the glad tidings as a surprise. It was strange how his buoyant spirits ebbed and his courage lost its fine edge as the train drew near the village. With the old timidity he walked into his own house and found his wife at the piano. The crashing chords subsided and she said abruptly:

"You made such a mystery of going to Portland, Charles, that I hope you are ready to explain. Why didn't you tell me the night before instead of leaving that silly note?"

He beamed with honest delight as he laughed and replied:

"It sounded too good to be true. I really didn't dare give it away. You can have the hired girl and the automobile, my dear. I am promoted to the Fannie Ellsworth and there's no Yankee skipper afloat that has the best of me. What do you think of that?"

"Why, how perfectly absurd it is!" she started to exclaim, but repented of the cruel slur and lamely concluded: "I mean, I took it for granted you would have to stay in the Haskell and—and I couldn't believe my ears. I have heard you mention the Ellsworth vessels, of course. How in the world did it happen?"

This thoughtless assumption that there was no merit in him, that his splendid fortune was undeserved cut him to the heart. It was the saddest moment of his married life. His lip quivered and his eyes were suffused as he gently told her:

"A man in my trade has to win such an honor without any pull or favor. I was hoping you'd like to run down with me in the morning and look the ship over. And she is so elegant and comfortable that a trip to Norfolk would be a regular holiday for us."

"Go to sea in a coal-schooner? Why, Charles, how can you suggest it? Think of the discomforts!"

"This isn't a bit like the Haskell," he persisted. "It's more like living aboard a liner. And we are liable to have a fine spell of weather in November."

Stubbornly unheeding his affectionate argument, Sadie Marion exclaimed:

"I dislike the sea, Charles. As for going to Portland to-morrow, have you forgotten the State convention and my paper?"

"Sure enough! 'The Problem of the Home,' " murmured the skipper unconsciously ironical. "Well, it seems as if we had charted separate courses. Too bad; I'll say no more about it."

He drifted out and sauntered to the post-office, where a dozen neighbors shook his hand in congratulation. The evening mail contained a letter for Mrs. Charles Tredick which he regarded with some slight curiosity before tucking it in his pocket. It bore a Portland postmark and was addressed in a masculine hand, legible but raggedly scrawled. Sadie Marion's correspondents were mostly women, but he saw no cause for comment when he gave her the letter in her own room and returned down-stairs to wind up his accounts with the owners of the Haskell.

Mrs. Charles Tredick was singularly robust, a stranger to hysteria; but her bosom heaved and her glance was wild as, for the third time, she read the disclosure blazoned on a page of cheap note-paper. An anonymous letter!! She whispered these sinister words and moved quickly to bolt the door. The message ran:

"A friend warns you to he careful of your husband. There is a woman in the case. He has been devoted to her for some time. That is where his money goes. She may meet him in Norfolk next trip. He sees her as often as he can and you are foolish to keep your eyes shut."

The unselfish single-mindedness of Captain Tredick was utterly forgotten. The serpent of suspicion reared its horrid head. His urgent invitation had been a ruse to mislead her. Some other woman had tricked and flattered his simple wits and he might be planning to run away with the—with the "wretched paramour"—that was the phrase. Perhaps they had been together in Portland no longer ago than yesterday. The elocutionist, whose readings from Shakespeare had been so warmly applauded, was capable of dissembling emotion in this crisis. Pale but superbly calm, she descended to find her erring husband, who looked up from a bundle of vouchers to inform her:

"I'll be on deck to get breakfast without fail, my dear."

"No more sneaking off to Portland on mysterious errands while I am asleep?" she searchingly demanded.

"Well, I turned the trick, didn't I, Sadie Marion? It looks like good-by if you have to go to Augusta for the convention. I shall be ready for sea some time to-morrow."

In a flash she read her duty clear, but delayed announcing it until she had asked:

"Did you make any enemies while you were in the Haskell, Charles? There is no one who might cause trouble between you and your new owner? It's natural to wonder, you know. There is apt to be jealousy, isn't there?"

"Barring a sailor or two that needed the toe of a boot, the docket is clear," he innocently assured her. "I don't like the mate in the Fannie Ellsworth. I sized him up as a counterfeit and he took a prejudice to me. But first impressions may be wrong."

Sadie Marion bit her lip and made use of her superior intelligence. This hostile mate might have heard the scandalous story and used it for his own ends. At any rate, she had discovered that Charles had an enemy with a grievance. True or false, she could not afford to be indifferent to the ominous warning. As a devoted wife and helpmeet she proposed to safeguard her own interests in saving her husband from himself. In a softer voice, almost caressingly, she astonished him by saying:

"May I change my mind? Would it please you very much to have me go to Norfolk with you?"

"Thunder and guns! You bet it would!" he cried, leaping to his feet. "I was set all aback when you even refused to consider it. Why, my dear, it would be a honeymoon! I'll sign on a cabin-boy as an extra hand and you will think you are aboard your own yacht."

His eagerness was so genuine that her doubts seemed base and she blushed for shame, but a poisoned mind is hard to heal.

"Perhaps my problem should begin at home, Charles," said she. "Isn't that how you have felt about it? But you were too kind to hurt me by telling me so. I can send my paper to the secretary and let her read it to the convention. Shall I pack a trunk to-night?"

This was to him an event more momentous than taking command of the Fannie Ellsworth. The puckered lines of care beneath his eyes were magically erased. Of course, she had not meant to wound him. He must have misunderstood. Until midnight they toiled in preparation and Captain Tredick's wife found that she was not altogether pretending a youthful zestfulness. The excitement of the adventure caused her to forget herself. They were ready to close the house, leave the cat next door, and depart for Portland in the earliest morning train. The shipmaster gratefully reflected that his luck had turned.

The stately six-master had finished discharging coal, and the negro sailors, with hose and broom, had cleaned the decks and the white houses of dust and grime. In the cabin the elderly steward had scrubbed and polished, making up the beds with fresh linen. Everywhere the ship displayed the painstaking attention and order of the nautical routine, and it came as an amazing discovery to Mrs. Tredick, who had hitherto disdained to set foot on one of her husband's vessels. He had telephoned certain instructions from the office and there were bowls of roses upon the tables, a row of new books, a pile of magazines. The luxury and convenience of it all, the realization that she was the mistress with servants to wait on her, made the village home seem poor and shabby.

"But I didn't know, Charles," she tremulously reiterated.

"You wouldn't listen, Sadie Marion," he smiled, an arm about her waist.

He left her below and sent for a tug, for the wind had suddenly shifted to the westward and he was anxious to take advantage of it. Mr. Staunton, the mate, was in a surly humor and his breath smelt of liquor, but he kept the men busy and Captain Tredick refrained from comment. Riding high and empty, the towering bulk of the Fannie Ellsworth floated through the narrow fairway, seeming to shoulder smaller craft out of her path. Off the red light-ship the tall sails began to creep up the masts as the steam-winches gripped the halyards. Standing near the wheel, Mrs. Tredick, expecting much bustle and confusion, saw a few sailors moving without haste and her husband idling, with hands in his pockets. Very quietly the Fannie Ellsworth dropped the tug and filled away on her course to the southward.

Mr. Staunton lived aft, according to custom, and he joined them at dinner, his burly presence making the captain appear oddly insignificant. His manner toward Sadie Marion was floridly gallant, his stories well told and ranging over many seas in deep-water ships before he had sailed coastwise. She was impressed. He was the ideal sailor of romance. Captain Tredick glumly looked on, fingering his clipped mustache. At length he suggested:

"If you have finished eating, Mr. Staunton, suppose you relieve the second mate. He may be hungry, too."

"If you have finished eating, Mr. Staunton, suppose you relieve the second mate."

With an injured air the officer obeyed, while Mrs. Tredick frowned at her husband's marked discourtesy. He had nothing to say until she observed:

"Mr. Staunton was a captain himself until square-rigged ships went out of fashion. I think you ought to be more careful of his feelings."

"If I don't like his manners he can get his grub in the mess-room for'ard," was the emphatic rejoinder, which so disconcerted Sadie Marion that she gasped for breath. Never before had he asserted himself. The afternoon was warm and clear, the breeze steady, and with top-sails set the schooner did her six knots. The last traces of disorder were removed and Captain Tredick seemed to have nothing whatever to do. This perplexed his wife, who had imagined him as drudging through laborious days and nights. He strolled with her, read a magazine aloud, took a nap, and operated the phonograph.

"But you are more like a passenger, Charles," she uneasily expostulated when darkness closed down and the chill air made the warm cabin inviting. "You have not commanded as large a ship as this and some of the duties must be new to you. I should think you ought to be on deck at night."

"In good weather? What are the mates hired for? Oh, I run up now and then and take a look around. That's the dickens of it—a loafer's job—too much time on my hands. It explains why I wanted you as a shipmate, my dear."

It was too soon for her to discern that his was the master mind, disciplined, profoundly experienced, which ruled this complex fabric and its turbulent men. What new respect he had gained in her sight was due to his affluent environment. The impressive Mr. Staunton was far more convincing as a figure of authority.

For several days the voyage was placidly uneventful. It was, indeed, more like a yachting-cruise. Punctually a black sailor took another's place at the wheel, the meals were served at the stroke of the bell, and the watch on duty trimmed the sheets or worked at such odd jobs as splicing, painting, carpentry. Occasionally Captain Tredick consulted his charts, pencilled a straight line with ruler and dividers, or squinted at the sun through a sextant and covered a sheet of paper with figures. He gave the mates almost no orders, besides the courses to steer, and seldom went forward of the quarter-deck.

It was otherwise with Mr. Staunton, whose activity was incessant. His voice thundered in the bullying accents of the rough old school as he tramped to and fro. In the cabin, however, he was rather subdued, watching Captain Tredick from a corner of his eye and trying to fathom what kind of man he was. Sadie Marion thought him fascinating. In her heart was the instinctively feminine worship of physical strength and courage. She could fancy this hale, broad-shouldered viking amid peril of wreck and storm or beating down a mutinous crew. Continually tormenting her was the anonymous letter, but now it seemed impossible that the heroic Mr. Staunton should have employed so cowardly a weapon. It was evident, nevertheless, that he bitterly disliked Captain Tredick, scarcely veiling his contempt.

At the first opportunity she had furtively ransacked her husband's room for sign or token of another woman, but, baffled, she resolved to ply the mate with adroit hints. They of ten walked together on deck during the daylight watches, his breezy loquacity contrasting with the skipper's contented silences.

"A sweetheart in every port, they say of you sailors, Mr. Staunton," she began, with heightened color.

"Are they always to blame, Mrs. Tredick? It's a lonely life and we are a sentimental lot. A married man, now—that's another matter, but I've known the best of 'em to slip the tow-rope."

"How shocking!" she exclaimed. "I can't believe it. When they are young and reckless, I presume."

"Not always, ma'am. There is a soft streak that sometimes shows when a man passes forty. I have known cases of it. They sort of forget their bearings and tack into trouble. Then it's time for their wives to stand lookout. Nothing personal intended, Mrs. Tredick. I am stating a general proposition."

She could not help glancing at the master of the Fannie Ellsworth, who stood at the taffrail examining the dial of the log. The mate smiled to himself and waited until she said:

"Wouldn't it be a kindness to warn a wife, Mr. Staunton?"

"Perhaps so," he gravely answered. "Excuse me, while I slack off the fore-sheet."

That night the pleasant wind which had carried the vessel beyond the capes of the Delaware veered uncertainly, then died to a calm obscured by fog. A long swell heaved in from seaward and Captain Tredick frequently noted the barometer. During these visits below he seemed preoccupied, almost unaware of his wife's questions. When he delayed to put on oilskins she nervously insisted on knowing why, but he merely advised her to stop worrying and go to bed. Wide-eyed, she was rolled to and fro in her bunk, while the deck above her head resounded to the banging of blocks, the thump of boots, and the harsh noise of the winches. The untroubled monotony of the voyage had not prepared her to face an emergency.

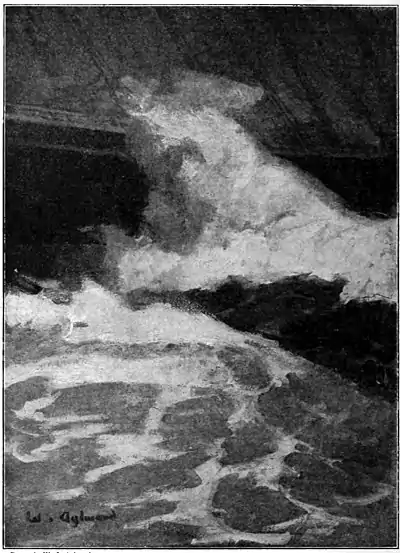

The northeast gale, presaged by Captain Tredick, swept down at dawn in blinding clouds of sleet and spray. Its devastating violence found the schooner with canvas reduced to three of her unwieldy lower sails and a couple of jibs. With no ballast in her cavernous hold she was the more difficult to handle. Little Captain Tredick peered rather sadly into the gray murk, reflecting that this was apt to be an unpleasant experience for his wife. It threatened to be what he called a "hoister" of a storm, such as strewed the coast with wreckage and had wiped two big schooners from the Ellsworth list during the preceding winter.

All his knowledge of tidal currents, soundings, drift, and leeway, added to the sailor's sixth sense, was brought into play to conjecture the position of the vessel since he had last seen a shore light. It was vital to know how many miles she was from the beach. Clinging to the rail, benumbed with cold, he watched the seas rear and break across the deck amidships. He had no fear of foundering, but to have his sails blown away was another matter.

The negro sailors, unfitted for such an ordeal as this, had fled into the fore-castle and were isolated by cataracts of water. A little while and the reefed mainsail split and was whirled away in streaming tatters. The wind was steadily increasing.

There was no getting aft with breakfast and Captain Tredick dived below to munch bread and cheese in the cabin pantry. His wife had managed to dress and was huddled upon the divan, deafened by the creaking and groaning of the woodwork, trembling to the shock of the hammering seas. To the unspoken appeal in her white face he shouted, tenderly holding her hand:

"A hard blow for you to be caught in, but we'll weather it, my dear."

She shook her head despairingly, with small faith in his ability to do the right thing at a time like this. He stood swaying to the giddy motion of the floor, the yellow oilskins dripping, a taut, reliant figure whose composure was flawless. He was absently staring at Sadie Marion, his mind engaged with a crucial decision, when Mr. Staunton tumbled down the stairs and announced in his stentorian voice:

"She will never work offshore at this rate, sir. We must get more sail on her somehow."

"I was trying to hold her where she was up to now," snapped Captain Tredick. "Work her offshore? What do you think you're in? I am going to let this vessel drive straight for the beach and anchor her in thirty fathom of water."

The mate's jaw dropped. His bewilderment was comic. Then he laughed derisively and bent over to shout in the captain's ear:

"Pile her up on a shoal? Drive for the beach instead of standin' off to get sea-room? That's one sure way to send us all to hell. If your ground-tackle don't hold"

"It was made to hold," interrupted the skipper, without heat. "You don't know what to do with a big schooner like this, Mr. Staunton. You have only sailed a few fair-weather voyages in her. It's sure disaster for one of 'em to be blown offshore in a gale like this."

"You never set foot in an Ellsworth schooner until this trip," truculently boomed the mate. "Anchor in thirty fathom? I'll have my say about that. All these lives at stake"

Captain Tredick raised a warning hand. It was an imperative gesture. He pursed his lips as though whistling softly. At this moment his distracted wife intervened. The habit of dominating Charles compelled her to speak. Clutching the table, she cried imploringly:

"Oh, you must listen to Mr. Staunton's advice! He knows best, I am sure. Please don't"

It was a transformed Captain Tredick that whirled to face her and brutally exclaimed:

"Not a word, Sadie Marion, not another word or I'll lock you in your room."

She babbled something, but he cut it short by seizing her arm in a bruising grip and pushing her ahead of him across the threshold. Turning the key, he thrust it in his pocket and returned to the mate, whose indignation provoked him to say:

"Mishandle a woman as well as a ship, eh? My turn next for giving you the plain truth?"

"Your turn next, you big, ignorant lubber," challenged Captain Charles Tredick. "Jump on deck. Go for'ard and drag out enough men to wear ship and steer the course I set. Shall I show you how?"

"Anchor with the lee shore under our bow, in a murderin' gale of wind?" growled the other.

A light chair was lashed against the wall with twine. The sinewy hands of Captain Tredick plucked it loose and, as a bludgeon, he swung it in a sidelong blow. It crashed and splintered against the head of Mr. Staunton, who fell sprawling. Slowly he scrambled to his knees, blood trickling from a cut above the ear. He was sick and dizzy. Captain Tredick stood over him, a leg of the chair in his fist, and declaimed:

"Do you want any more, you drunken tramp? I took your measure the first day out. Get a bandage-roll from the medicine-closet and tie yourself up. Then come a-running."

"Do you want any more, you drunken tramp?"

A wail from the imprisoned Sadie Marion punctuated the cowed silence of the mate. Captain Tredick raced on deck and the two weary negroes at the wheel turned their eyes to him in pathetic hopefulness. He stretched a line forward as far as he dared venture unaided and waited for Mr. Staunton, who presently emerged from the hatchway. Together they fought the cruel weight of water that poured over the smashed bulwarks, and, tumbling into the fore-castle, they pulled sailors from their bunks and tossed them on deck to sink or swim.

It was the intrepid soul of Captain Tredick waging a contest against tremendous odds. Before nightfall the Fannie Ellsworth, with no more than a rag of canvas left, was riding to her ponderous anchors within two miles of the Virginia beach. Her cables had been forged and welded for such peculiar stress as this. The gale screamed in the rigging and the combers broke over her bows, but it was with a sense of serene security that Captain Tredick went below to change his clothes. Mr. Staunton had found lodgings at the other end of the ship. With this discord removed, the husband of Mrs. Tredick attempted reconciliation. It was a task to dishearten a mariner less indomitable. The print of his fingers was black and blue on her arm. The insult was even more poignant. To make it absolutely unforgivable, he expressed no regrets.

Before nightfall the Fannie Ellsworth ... was ... within two miles of the Virginia beach.

His demeanor was affectionate, solicitous, but never humble. Until the gale spent its force, two days later, she stayed in bed, watching him through the doorway as he read and smoked with his heels on the table. It dawned upon her, as a curious phenomenon, that she was afraid of him. Certainly she had learned to respect him. This gave her much to think about.

There was still a barrier of constraint between them when the Fannie Ellsworth set her spare sails and resumed the voyage to Norfolk over an ocean sparkling and friendly. Mrs. Tredick sought a sheltered nook on deck, with rugs and pillows, and the buoyant air revived her. With vision no longer blinded, she studied her husband, the ship, the crew. And little by little she came to perceive that his quiet personality was all-pervasive, his mastery of his trade implicitly acknowledged. He was wiser and stronger than all the rest, and old Marvin Ellsworth had not blundered in choosing him.

During the last evening at sea they sat in the cabin together. The swinging lamp cast a cheery illumination. The room was very homelike. Sadie Marion was loath to forsake it. Was her companionship really dear to him? What about the other woman? She was in a mood to make confession, but would he be as frank with her? Timidly she exclaimed:

"I was greatly mistaken in the character of Mr. Staunton, Charles. I believe he would stoop to tell a lie to satisfy a grudge."

"That cheap hound?" was the careless comment. "I intend to throw his duds on the wharf as soon as we make fast. He fooled you, Sadie Marion, but women are built that way. He is a grand-looking object, no doubt about it."

"Supposing he had lied about you in a letter to me," she bravely resumed.

"In a letter? Well, I'd make him eat it, for one thing. But you would take no stock in such nonsense, so what's the difference?"

"But perhaps I did, Charles, and it has made me too dreadfully miserable for words. I have been a selfish, stupid, unfeeling woman."

"You are an angel and always were," devoutly exclaimed Captain Tredick. "It makes me blue to feel that you won't care to sail with me again, after that gale o' wind and the rumpus in the cabin."

"In all weather, fair and foul, if you will only ask me," was the wistful response.

"I'm perfectly delighted. You see, my dear, your only chance to get really acquainted with me was aboard my vessel."

"You are a very wonderful man afloat," was her final surrender. "But you will be angry, and maybe abuse me again, when you know the motive that changed my mind about coming in the schooner. I—I will get the letter and read it to you, and will you look me right in the eyes and say whether it is true or false?"

"I'll swear it on a stack of Bibles as high as the cross-trees if that will be any comfort to you," declared her husband.

She fumbled in her hand-bag and produced the sheet of paper, which was creased with many readings. Captain Tredick's countenance was austere and inscrutable. Unsteadily she recited, halting between the hateful sentences:

"A friend warns you to be careful of your husband. There is a woman in the case. He has been devoted to her for some time. That is where his money goes. She may meet him in Norfolk next trip. He sees her as often as he can, and you are foolish to keep your eyes shut."

Silence followed the indictment. The very sound of it moved Sadie Marion to tears. Captain Tredick shifted in his chair, drew a long breath, gazed up at the skylight, and deliberately affirmed:

"It is all true, so help me, Sadie Marion."

"All true?" she faintly echoed.

"Of course it is. There was no other way to budge you. I wrote it myself."

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1925, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 95 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.