LECTURE XXX.

"I'm sure a woman might as well be buried alive as live here. In fact, I am buried alive; I feel it. I stood at the window three hours this blessed day, and saw nothing but the postman. No: it isn't a pity that I hadn't something better to do; I had plenty: but that's my business, Mr. Caudle. I suppose I'm to be mistress of my own house? If not, I'd better leave it.

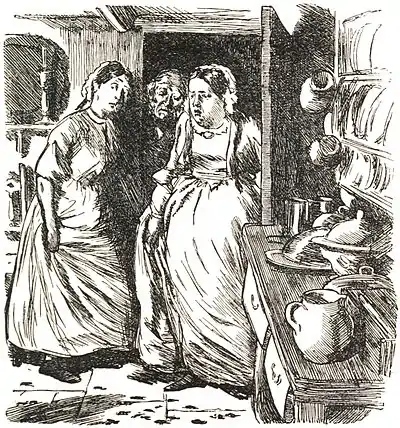

MRS. CAUDLE VISITS THE KITCHEN—"MILLIONS OF BLACK-BEETLES!"

"And the very first night we were here, you know it, the black-beetles came into the kitchen. If the place didn't seem spread all over with a black cloth, I'm a story-teller. What are you coughing at, Mr. Caudle? I see nothing to cough at. But that's just your way of sneering. Millions of black-beetles! And as the clock strikes eight, out they march. What?

"They're very punctual?

"I know that. I only wish other people were half as punctual: 'twould save other people's money and other people's peace of mind. You know I hate a black-beetle! No: I don't hate so many things. But I do hate black-beetles, as I hate ill-treatment, Mr. Caudle. And now I have enough of both, goodness knows!

"YOU KNOW I HATE A BLACK-BEETLE!" |

"Why don't I poison 'em?

"A pretty matter, indeed, to have poison in the house! Much you must think of the dear children. A nice place, too, to be called the Turtle Dovery!

"Didn't I christen it myself?

"I know that,—but then, I knew nothing of the black-beetles. Besides, names of houses are for the world outside; not that anybody passes to see ours. Didn't Mrs. Digby insist on calling their new house 'Love-in-Idleness,' though everybody knew that that wretch Digby was always beating her? Still, when folks read 'Rose Cottage' on the wall, they seldom think of the lots of thorns that are inside. In this world, Mr. Caudle, names are sometimes quite as good as things.

"That cough again! You've got a cold, and you'll always be getting one—for you'll always be missing the omnibus as you did on Tuesday,-and always be getting wet. No constitution can stand it, Caudle. You don't know what I felt when I heard it rain on Tuesday, and thought you might be in it. What?

"I'm very good?

"Yes, I trust so: I try to be so, Caudle. And so, dear, I've been thinking that we'd better keep a chaise.

"You can't afford it, and you won't?

"Don't tell me: I know you'd save money by it. I've been reckoning what you lay out in omnibuses; and if you'd a chaise of your own—besides the gentility of the thing—you'd be money in pocket. And then, again, how often I could go with you to town,—and how, again, I could call for you when you liked to be a little late at the club, dear! Now you're obliged to be hurried away, I know it, when, if you'd only a carriage of your own, you could stay and enjoy yourself. And after your work you want enjoyment. Of course, I can't expect you always to run home directly to me: and I don't, Caudle; and you know it.

"A nice, neat, elegant little chaise. What?

"You'll think of it?

"There's a love! You are a good creature, Caudle; and 'twill make me so happy to think you don't depend upon an omnibus. A sweet little carriage, with our own arms beautifully painted on the panels. What?

"Arms are rubbish; and you don't know that you have any?

"Nonsense: to be sure you have—and if not, of course they're to be had for money. I wonder where Chalkpit's, the milkman's arms, came from? I suppose you can buy 'em at the same place. He used to drive a green cart; and now he's got a close yellow carriage, with two large tortoise-shell cats, with their whiskers as if dipped in cream, standing on their hind legs upon each door, with a heap of Latin underneath. You may buy the carriage if you please, Mr. Caudle; but unless your arms are there, you won't get me to enter it. Never! I'm not going to look less than Mrs. Chalkpit.

"Besides, if you haven't arms, I'm sure my family have, and a wife's arms are quite as good as a husband's. I'll write to-morrow to dear mother, to know what we took for our family arms. What do you say? What?

"A mangle in a stone kitchen proper?

"Mr. Caudle, you're always insulting my family—always: but you shall not put me out of temper to-night. Still, if you don't like our arms, find your own. I daresay you could have found 'em fast enough, if you'd married Miss Prettyman. Well, I will be quiet; and I won't mention that lady's name. A nice lady she is! I wonder how much she spends in paint! Now, don't I tell you I won't say a word more, and yet you will kick about!

"Well, we'll have the carriage and the family arms? No, I don't want the family legs too. Don't be vulgar, Mr. Caudle. You might, perhaps, talk in that way before you'd money in the Bank; but it doesn't at all become you now. The carriage and the family arms! We've a country house as well as the Chalkpits! and though they praise their place for a little paradise, I dare say they've quite as many blackbeetles as we have, and more too. The place quite looks it!

"Our carriage and our arms! And you know, love, it won't cost much—next to nothing—to put a gold band about Sam's hat on a Sunday. No: I don't want a full-blown livery. At least, not just yet. I'm told that Chalkpits dress their boy on a Sunday like a dragon-fly; and I don't see why we shouldn't do what we like with our own Sam. Nevertheless, I'll be content with a gold band, and a bit of pepperand-salt. No: I shall not cry out for plush next; certainly not. But I will have a gold band, and ——

"You won't; and I know it?

"Oh yes! that's another of your crotchets, Mr Caudle; like nobody else—you don't love liveries. I suppose when people buy their sheets, or their tablecloths, or any other linen, they've a right to mark what they like upon it, haven't they? Well, then? You buy a servant, and you mark what you like upon him, and where's the difference? None, that I can see."

"Finally," says Caudle, "I compromised for a gig; but Sam did not wear pepper-and-salt and a gold band."