LECTURE XXVI.

"You're glad of it?

"Well, you must have a heart to say that. I declare to you, Caudle, as true as I'm an ill-used woman, if it wasn't for the dear children far away in blessed England—if it wasn't for them, I'd never go back with you. No: I'd leave you in this very place. Yes; I'd go into a convent; for a lady on board told me there was plenty of 'em here. I'd go and be a nun for the rest of my days, and—I see nothing to laugh at, Mr. Caudle; that you should be shaking the bed-things up and down in that way. But you always laugh at people's feelings; I wish you'd only some yourself. I'd be a nun, or a Sister of Charity.

"Impossible?

"Ha! Mr. Caudle, you don't know even now what I can be when my blood's up. You've trod upon the worm long enough; some day won't you be sorry for it!

"Now, none of your profane cryings out! You needn't talk about Heaven in that way: I'm sure you're the last person who ought. What I say is this. Your conduct at the Custom House was shameful—cruel! And in a foreign land, too! But you brought me here that I might be insulted; you'd no other reason for dragging me from England. Ha! let me once get home, Mr. Caudle, and you may wear your tongue out before you get me into outlandish places again.

"What have you done?

"There, now; that's where you're so aggravating. You behave worse than any Turk to me,—what?

"You wish you were a Turk?

"Well, I think that's a pretty wish before your lawful wife! Yes—a nice Turk you'd make, wouldn't you? Don't think it.

"What have you done?

"Well, it's a good thing I can't see you, for I'm sure you must blush. Done, indeed!

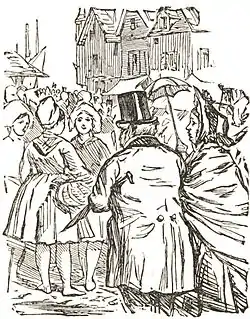

"Why, when the brutes searched my basket at the Custom House!

"A regular thing, is it?

"Then if you knew that, why did you bring me here?

No man who respected his wife would. And you could stand by, and see that fellow with mustachios rummage my basket; and pull out my night-cap and rumple the borders, and—well! if you'd had the proper feelings of a husband, your blood would have boiled again. But no! There you stood looking as mild as butter at the man, and never said a word; not when he crumpled my

"THE BRUTES SEARCHED MRS. CAUDLE'S BASKET AT THE CUSTOM HOUSE."

night-cap—it went to my heart like a stab—crumpled it as if it were any duster. I dare say if it had been Miss Prettyman's night-cap—oh, I don't care about your groaning—if it had been her night-cap, her hair-brush her curl-papers, you'd have said something then. Oh, anybody with the spirit of a man would have spoken out if the fellow had had a thousand swords at his side. Well, all I know is this: if I'd have married somebody I could name, he wouldn't have suffered me to be treated in that way, not he!

"Now, don't hope to go to sleep, Mr. Caudle, and think to silence me in that manner. I know your art, but it won't do. It wasn't enough that my basket was turned topsy-turvy, but before I knew it, they spun me into another room, and ——

"How could you help that?

"You never tried to help it. No; although it was a foreign land, and I don't speak French—not but what I know a good deal more of it than some people who give themselves airs about it—though I don't speak their nasty gibberish, still you let them take me away, and never cared how I was ever to find you again. In a strange country, too! But I've no doubt that that's what you wished: yes, you'd have been glad enough to have got rid of me in that cowardly manner. If I could only know your secret thoughts, Caudle, that's what you brought me here for, to lose me. And after the wife I've been to you!

"What are you crying out?

"For mercy's sake?

"Yes; a great deal you know about mercy! Else you'd never have suffered me to be twisted into that room. To be searched, indeed! As if I'd anything smuggled about me. Well, I will say it, after the way in which I've been used, if you'd the proper feelings of a man, you wouldn't sleep again for six months. Well, I know there was nobody but women there; but that's nothing to do with it. I'm sure, if I'd been taken up for picking pockets, they couldn't have used me worse. To be treated so—and 'specially by one's own sex!—it's that that aggravates me.

MR. CAUDLE ADMIRES THE FISH-WOMEN. |

"What could you do?

"Why, break open the door; I'm sure you must have heard my voice: you shall never make me believe you couldn't hear that. Whenever I shall sew the strings on again, I can't tell. If they didn't turn me out like a ship in a storm, I'm a sinner! And you laughed!

"You didn't laugh?

"Don't tell me; you laugh when you don't know anything about it; but I do.

"And a pretty place you have brought me to! A most respectable place, I must say! Where the women walk about without any bonnets to their heads, and the fish-girls with their bare legs—well, you don't catch me eating any fish while I'm here.

"Why not?

"Why not,—do you think I'd encourage people of that sort?

"What do you say?

"Good-night?

"It's no use your saying that—I can't go to sleep so soon as you can. Especially with a door that has such a lock as that to it. How do we know who may come in? What?

"All the locks are bad in France?

"The more shame for you to bring me to such a place, then. It only shows how you value me.

"Well, I dare say you are tired. I am! But then, see what I've gone through. Well, we won't quarrel in a barbarous country. We won't do that. Caudle, dear,—what's the French for lace? I know it, only I forget it. The French for lace, love? What?

"Dentelle?

"Now, you're not deceiving me?

"You never deceived me yet?

"Oh! don't say that. There isn't a married man in this blessed world can put his hand upon his heart in bed and say that. French for lace, dear? Say it again.

"Dentelle?

"Ha! Dentelle! Good-night, dear. Dentelle! Den—telle."

"I afterwards," writes Caudle, "found out to my cost wherefore she inquired about lace. For she went out in the morning with the landlady to buy a veil, giving only four pounds for what she could have bought in England for forty shillings!"