XIII.

THE DESTRUCTION OF

MEDIÆVAL LEICESTER.

THE destruction of mediæval Leicester began with the passing of the Plantagenets and the dismantling of Leicester Castle. Fifty or sixty years later, the zeal of the religious reformer swept away many of the most characteristic and beautiful monuments of mediæval art. Other lingering remains of the Middle Age were afterwards allowed to fall into decay, and, within the last 150 years, many have been deliberately destroyed, under the blind pressure of growing life. Only a few are still to be found.

The Castle of Leicester, the great "Palace of the Midlands during the most splendid period of the Middle Ages," may be said to have passed its meridian glory in the lifetime of John of Gaunt. But long after his death it retained its old prestige. On the 18th of February, 1425-6, the Parliament of England assembled in its great Hall, and again met there, in all probability, on the 29th of April, 1450, when they had adjourned to Leicester from Westminster in consequence of the insalubrity of the Thames air. The last authentic record of its occupation seems to be a letter written by Richard the Third to the King of France, which is dated August 18th, 1483, "from my Castle of Leicester." In the reign of Henry VII it fell into disuse. When John Leland saw it, sometime about the year 1536, it had already lost its ancient pride. "The Castle," he wrote, "standing near the West Bridge, is at this time a thing of small estimation." Royal Commissioners, appointed by Henry VIII, reported that it was rapidly deteriorating; and, although a Constable of the Castle was nominated, little was done to prevent its decay.[1] The only part preserved was the great Hall. The spacious yard of the Castle, which so many a time had been gay with the flower of England's chivalry, began to be made use of as a pound for

A hundred years later, a survey of the Castle was made, from which it appears that the Hall, a great Chamber, a Parlour, a great Kitchen, a larder and a dungeon, with out-offices, were then standing, in very bad repair.

The siege of Leicester in 1645 did further damage to the ruined fabric; and, early in the following century, the eastern side of the Hall was taken down and replaced by a brick front. At the same time the Kitchen was converted into a coach-house. The division of the great Hall into two separate Courts — a civil and criminal court, with an entrance lobby between them and a grand jury room above it — was effected, according to Thompson, in the year 1821, involving, as he remarked, "an entire sacrifice of all the historic and venerable associations of the fabric," The old Castle House was then entirely demolished. There remain at the present day (1) the ancient Norman Hall, almost entirely concealed beneath a modern disguise; (2) the Tudor Gateway and Porter's Lodge, near the North door of St. Mary's Church; (3) the Dungeon, or Cellar;[2] (4) the Turret Gateway leading into the Newarke, which is said to have been reduced to its present ruinous condition during a tempestuous election in 1832; and (5) Part of Southern defence. About the middle of the 16th century, the outward appearance of Leicester suffered a remarkable change The fine old church of the Abbey, and most of the monastic buildings, were dismantled; the three great religious Houses of the town were levelled with the ground; the churches were stripped of their ornaments and images, and all other "monuments of superstition," and the lovely Collegiate church of the Newarke was utterly destroyed. Before the end of the century, the Berehill Cross, and most of the other Town Crosses, were pulled down, the ancient Hospital of St. John was converted into a WoolHall, and the property of all the religious Guilds and Colleges was taken away from them, and passed, in many cases, into the hands of speculators.

The effects of the 16th century cataclysm may be summarised thus:—

Two old churches had then already fallen into disuse; St. Michael's had disappeared, and St. Peter's was fast becoming a ruin. Five other parish churches in the town, those of St. Nicholas, St. Margaret, All Saints, St. Mary and St. Martin, survived the storm, stripped almost bare and impoverished, but structurally intact, and they still exist. The little church of St. Leonard survived for about a hundred years more.

The church of the Abbey, the church of the Grey Friars, the church of St. Clement, the church of the Austin Friars and the Newarke church were all dismantled or destroyed. The chapel of St. Sepulchre, or St. James, and the chapel of St. John in Belgravegate were left to decay, and fell into ruins. The little chapel on the West Bridge was converted into a dwellinghouse. The Hospital of St. John, after the failure of the WoolHall, was replaced by new almshouses, and the adjoining church of the Hospital made room for a Town Prison. The fate of Wigston's Hospital has been related already. The Hall and Chantry Houses of the Guild of Corpus Christi were bought by the Town, and are still in existence.

Some parts of the ancient walls of the Abbey may yet be seen, and particularly the brick wall in Abbey Lane, built by Bishop John Penny, at the beginning of the 16th century, which still bears his initials, wrought in ornamental brickwork, and one lonely niche, long bereft of its tutelary image. And it is probable that Penny's alabaster tomb, now in the chancel of St. Margaret's Church, was moved thither from the Lady Chapel of the Abbey, though on this point antiquarians differ.

The only existing relic of the Friars' houses may be a small portion of the boundary wall of the Grey Friars' monastery, to which Mr. Henry Hartopp has called attention. This is a red brick wall which stands in Peacock Lane, opposite the site of the chapel of Wigston's Hospital. It is of the same date as Bishop Penny's wall, or possibly rather earlier, and it must, therefore, it would seem, have formed part of the northern boundary of the Grey Friars' property. It is possible that some fragments of the southern wall may also survive, for it is only seventy years since Mr. Stockdale Hardy called attention to some "slight and dispersed portions of the boundary walls," and stated that "the chambers of a few houses in what is still called Friars' Lane now rest upon some of them." Fragments of St. Mary's College seem to survive about Bakehouse Lane.

Little of the ancient Newarke is now left. Throsby said that the foundations and ruins of the College were finally demolished about the year 1690. The following buildings are existing at the present day:—

(1) The massive 14th century entrance Gate of the College, now known as the Magazine Gateway, remains practically unaltered within, although the exterior has been recased. Until 1904 all the traffic to and from the Newarke passed under this archway, but in that year it was diverted to a new road on the north side of the Gate.

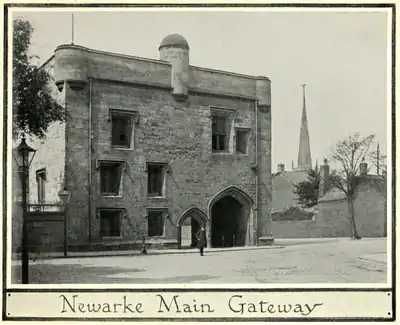

(2) The Turret Gateway, before referred to. A drawing of this Gateway was made by John Flower before its partial destruction in 1832, an engraving of which will be found in the Literary Remains of John Stockdale Hardy. Mr. Hardy, who died in 1849, occupied a neighbouring house, and he is said to have sustained "the structure of this ancient gateway at his own expense," thus preserving to Leicester "one of the few existing memorials of its former state."

(3) The Trinity Hospital. The original house was first restored about 1776. In recent years it has been almost entirely re-built, only part of the old building being left. The chapel, however, yet remains, enriched by several objects salved from various wrecks, such as the recumbent effigy taken from the Collegiate Church, and the carved oak fronts of seats and altar rails removed from Wigston's Hospital.

(4) The 14th century house which is now used as St. Mary's Vicarage was probably at one time the residence of the Dean of Newarke College. Externally this dwelling retains much of its ancient appearance.

(5) Portions of the West, South and East boundary walls of the Newarke enclosure were standing in recent years, and fragments of "Rupert's Tower," as the South Gate has been named, may yet be found. There are traces of walls in Bonner's Lane, built into several cottages and into a warehouse or engineer's shop. Some good illustrations of the old boundary walls of the Newarke, as they appeared in 1838, and a view of Rupert's Tower in 1821, will be found in Mr. J. F. Hollings' pamphlet on "Leicester during the great Civil War," which was published at Leicester in 1840.

(6) The dwelling-house erected in 1512 by William Wigston near the Turret Gateway, has lately escaped destruction. It was the chantry-house of the two priests of Wigston's Chantry in the Collegiate Church of the Newarke, and bears above its door-way the arms of the founder. When its destruction was threatened, about ten years ago, a determined effort to save it was made on the initiative of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society, with the active co-operation of Mr. Sydney A. Gimson, who was then Chairman of the Leicester Museum and Art Gallery Committee. Nearly £3,600 were then subscribed, and the chantry house and two adjoining Jacobean houses with their gardens were assigned to ten gentlemen who had secured an option of purchasing them for the benefit of the town, upon the understanding that, as soon as the property could be freed from all burden of debt, it should be transferred to the Corporation of Leicester, to be preserved as an historical memorial of the past, and in the hope that it would be used as a Leicester and County Museum, dealing specially with matters of local interest. There is still a debt of £5,500 on the property, which must be cleared off before this excellent scheme can be completed but one may feel confident that some of Leicester's patriotic and prosperous citizens will quickly grasp this remarkable opportunity of doing a lasting service to their City.

(7) Two pointed arches, which form part of the cellar wall of an old house now standing on part of the site of the Church of Our Lady of the Newarke, and the effigy of a lady removed to the chapel of Trinity Hospital, are all that remain from the wreck of the Collegiate Church.

The mediaeval Walls of Leicester were originally kept in repair at the expense of the community, and with the help of murage tolls. During the 13th century they were maintained in good order. In the following century also, as the Borough Records show, they were from time to time repaired. A pit, for example, on one of the walls, in which corn grew up, was filled in with sand and gravel; and trees that had grown up in the Town Ditches were cut down. But the stones were tempting to builders, and the broad ditches under the walls' shelter offered desirable ground for the cultivation of fruit and vegetables. Long before 1500 the old fortifications began to assume a picturesque and peaceful aspect. The crumbling walls and the slopes of the outer ditches, which varied in width from 40 to 47 feet, were parcelled out, by the year 1492, in small plots among some eighty different holders. They were used mainly as gardens and orchards, but on some parts of the wall, and in the ditches, houses and barns had been built. Upon one strip of land, 40 feet wide and 430 feet long, between the Town Wall and Churchgate, were two pairs of butts, held by the "commons of Leicester," for the practice of archery. In 1587 the walls were described by the Town Clerk as "ruinous"; and in 1591 an order was made that no stone should be taken from the Town Walls without the license of a common hall. Queen Elizabeth paid a keeper of the walls £4 5s. 4d. annually, but this "Wallership," which concerned the Castle and Newarke walls only, may have been a sinecure. A lady who visited Leicester towards the end of the 17th century, wrote in her Diary:— "Ye walls now are only to secure gardens that are made of ye ruined places that were buildings of strength." A few of these gardens that were sheltered by the mediæval stone walls of the town survived into modern times, but the walls have now disappeared, and only a few scattered fragments remain. Portions of the East Wall may perhaps yet be seen between East Bond Street and Churchgate; and near Cumberland Street, out of which runs a "City Wall Street," may be traced some relics of the old North Wall.

The ditches outside the town Walls were not entirely filled up for some centuries. One day in 1714 or 1715, a certain Mrs. Dickman, when walking home from St. Margaret's Church along Churchgate, was unexpectedly rescued from oblivion by a sudden storm of wind, which carried her off her feet, and "blew her into the Town Ditch." This ditch remained till the middle of the 18th century.

Most of the other walls in the town were made of mud. When saltpetre was urgently required in the reign of Queen Elizabeth for the manufacture of gunpowder, it was proposed that all the mud walls within the borough should be broken down in order that supplies might be obtained. The Mayor then stated that, if this proposal were carried out, the damage done to the town would amount to "1,000 marks or thereabouts," that is to say, between £650 and £700 of that day's money, and many thousands of pounds of ours. There must therefore have been a very considerable number of mud walls. Only a few of them lasted into our own times, which old inhabitants will remember, such as the remnants which lingered on the boundary of the old shooting butts in Butt Close Lane, and a wall which was standing within recent memory in Newarke Street.

The four Gates, or Gatehouses, of the town were kept in better repair than the walls, and they remained standing until the year 1774. They were then all pulled down to meet modern requirements, having been sold by auction at the Three Crowns Hotel, in four lots, as building material. But the width of the entrances was not altered for some years. Throsby complained that only "the humble roofs of the Gates were sold in 1774, being considered as obstacles to the passage of a lofty load of hay or straw. The walls which supported these roofs were left standing in general."

Of the old stone Bridges, which served the needs of the town for many centuries, one, the North Bridge, was washed away by a flood in 1795. The other three were demolished in the 19th century, as they then proved insufficient to carry the constantly increasing traffic.

The Houses of Leicester, throughout the Middle Ages, were built of wood and plaster, and either thatched or, in some cases, covered with Swithland slates. Stone was used occasionally in a few important buildings, but brick was hardly, if at all, employed in the construction of houses at Leicester until the end of the 17th century. In the Town Chamberlains' Accounts bricks are never mentioned before the year 1586, when "lyme, ston, and brycke" were used for building the conduit head in St. Margaret's Field. When John Leland visited the town about 1536, he remarked that "the whole town of Leicester at this time is builded of timber;" and, more than a hundred years later, it presented very much the same appearance to John Evelyn, who calls it in his Diary "the old and ragged city of Leicester." At the end of the 17th century another visitor described the town as "old timber building, except one or two of brick."

The most interesting examples of domestic architecture, besides the Wigston Chantry House, and the old Vicarage of St. Mary's, which survived into modern times were the following:(1) An old house in High Cross Street, now known as Wigston House.

(2) The old "Parliament House," in Redcross Street.

(3) The Blue Boar Inn.

(4) An old house in St. Nicholas Street associated both with Bunyan and Wesley.

(5) The "Lord's Place," in the present High Street, with the Porter's Lodge and Gardener's Cottage.

(6) The Old Barn, in Horsefair Street.

(7) The Confratery of Wigston's Hospital.

(8) Some old timbered houses in Little Lane and Highcross Street.

(1) This house was formerly supposed to have been a Chantry House of the Guild of St. George, The original front was taken down in 1796, and the ancient stained glass, which then filled the long range of windows that look on to the courtyard of the house, was taken away. This glass has been carefully preserved, having been for many years in the possession of the Leicestershire Archaeological Society, and it is now displayed in the City Museum. It has been reproduced in colour in the Transactions of the Society, which at the same time published an elaborate description of the various panels, written by Thomas North. The Hall of the Guild of St. George stood on the eastern side of St. Martin's Church, beyond the Maiden Head Inn, and it is very doubtful if the house in the old High Street was ever owned by that Guild. It is thought now that it was the dwelling-place of some wealthy burgess. The original building and the stained glass seem both to belong to the reign of Henry VII, and it is conjectured (mainly on account of the initials R. W. inscribed on two of the pieces of glass), that the house may have been built and occupied by Roger Wigston, who was Mayor of Leicester in 1465, 1472 and 1487, and M.P. for Leicester in 1473 and 1488. He died in 1507, and was buried in the Lady Chapel of St. Martin's Church.

(2) This old house was always called the "Parliament House," on account of a tradition which maintained that Parliament had once met there. It was pulled down, unfortunately, in the last century, but there is a very good illustration of it, showing the heraldic devices displayed upon its front, in Mrs. Fielding Johnson's "Glimpses of Ancient Leicester." It is on record that Parliament met on February 18th, 1425-6, in the great Hall of Leicester Castle. Both Lords and Commons there listened to a speech of Cardinal Beaufort, Bishop of Winchester and Chancellor of England, after which the Commons were directed by the Chancellor to assemble "in quadam bassa camera," to elect a Speaker. The accommodation provided by the "Parliament House" would answer to this description, and as the house stood hard by the Castle, one might reasonably accept the local tradition, and conclude that the Commons really met in the "low chamber" of this ancient dwelling-place.

(3) The Blue Boar Inn remained in existence, although not used as an Inn, until 1836. "The Blue Boar," wrote James Thompson in 1844, in his Handbook of Leicester, "was taken down a few years since by a speculating builder to erect some modern houses upon its site. Whilst its previous owner (Miss Simons, a lady of the old school) was alive, it was preserved from the hand of the destroyer; but on her death no one was found to rescue this relic of national interest from its destruction."

(4) This old house, in which John Bunyan lodged, according to local tradition, in the reign of Charles II, and which John Wesley occupied in the next century, was standing in St. Nicholas Street not many years ago, but has now disappeared.

(5) A house in the Swinesmarket, known as "Reynold's House," was purchased by the Earl of Huntingdon in 1569, and thenceforth, under the name of "Lord's Place," became the town-house of his family. Several royal visitors were there entertained, including Mary Queen of Scots and Charles I. The house itself, though perhaps not all the grounds, belonged at one time to the family of Reynolds, who provided Leicester with so many Mayors. It was bought in 1540 by Nicholas Reynold, who was Mayor in 1531 and 1539. On the East it was bounded by the George, on the West by a messuage belonging to the King, and it extended on the North as far as Soapers' Lane. The grounds of Lord Huntingdon's house seem to have been more extensive; and it is thought that an old house called "The Porter's Lodge," formerly standing at the corner of South and East Bond Streets, lay at the north-east entrance of his property. An old building, still to be seen at the junction of Free School Lane and West Bond Street, and known as "The Gardener's Cottage," may also have belonged to the Place. One of the lofty stone turrets of this mansion, concealed in 18th century brickwork, survived until the year 1902, when the premises to which it belonged were demolished.

(6) Among the real estate granted to the Mayor and Burgesses of Leicester by Queen Elizabeth's Charter of 1589 was "an old Barn with the Barn-yard in Horsefair Street." This ancient building may perhaps have been the "Fermerie" of the Grey Friars, in which the Commons met in 1414. After many generations, it was adapted to another use, being converted, in the year 1752, into a place of worship for Methodists. Twenty years later, John Wesley preached in the great building to very large congregations. It was taken down in 1787.

(7) The very picturesque old house of the Confrater of Wigston's Hospital stood in High Cross Street, and was destroyed in 1875.

(8) A few old timbered houses of ancient date are to be found in High Cross Street, at the corner of Red Cross Street, and in Little Lane. The White Lion Inn, between Cank Street and the Market Place, probably dates from the reign of Queen Elizabeth, but has been much altered.

The Free Grammar School, built in 1573 out of the ruins of St. Peter's church, was closed as a school in 1841. It is still standing, at the corner of High Cross Street and Free School Lane, being now used as a carpet warehouse. The arms of Queen Elizabeth and those of the Borough of Leicester are united upon its front. It is a plain structure of little beauty. There are, in fact, in modern Leicester scarce half a dozen buildings left, apart from the five old churches, in which the genuine spirit of the Middle Age is still able to charm.

- ↑ The Constable's Salary was only £3 0s. 4d, a year, less than that of any other Castle Keeper in England.

- ↑ Mr. A. Hamilton Thompson writes: "I suppose this may be the 'dungeon' referred to in the 17th century survey, at a date when the term had long been applied to vaults of a prison-like appearance. But 'dungeon,' in surveys and technical documents of an earlier date, is habitually used in the proper sense of 'donjon,' as equivalent to the great tower or keep of a castle. The word dunio is applied primarily to the earthen mount of a castle, then to the buildings of wood or stone upon it, and then to the keep, whether built on a mount or standing by itself. The term 'dungeon,' in the sense of prison, seems to arise from the presence of vaults, not necessarily prisons, in such towers. I rather wonder whether, at the date of the survey, the keep on the mount may not have been standing still in bad repair."