MADE IN GERMANY

By Temple Bailey

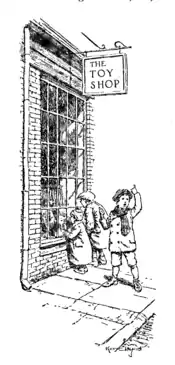

DOROTHEA'S little shop was at the very edge of the residence district, on the boundary line, as it were, of business. At first she had sold only needles and pins and thread and collar bones and embroidery silks and ruching and ink and paper and post-cards. Then one Christmas she had added a few toys, and since then her small place had been known quite prominently as the Toy Shop.

For Dorothea was a genius at discovering toys that the youngsters wanted. She was so much of a child herself, in spite of the silver threads which shone faintly through her fair hair, and in spite of the tiny wrinkles which encroached on the pink-and-white of her complexion.

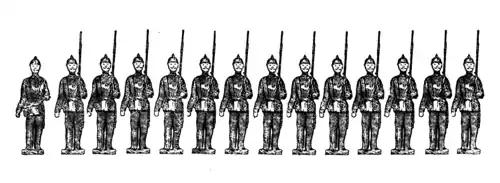

The needles and pins and ink and collar bones were side issues now, for the little shop overflowed with lead soldiers and woolly sheep and furry cats and things that had to be wound up, and things that barked when you pulled a string, or mewed when you tipped them upside down, or ran on wheels when you put them on the floor. And all the cases were crowded with dolls that talked and dolls that walked, and dolls that went to sleep, and dolls that simply smiled and did nothing. And there were little china dishes heaped with such natural-looking food that you really couldn't believe that the spinach and the eggs and the puddings and the pies and the sausages and the salads weren't ready to eat on the spot! There were little iron cook-stoves, and houses with all the furniture in them to the very last footstool, and with bathtubs and electric lights; and there were railroads that led up to the most wonderful tin mountains, with tin trains that stopped at tin stations, and with tin signals and bridges.

And every one of these wonderful toys was "made in Germany."

Dorothea, coming in one dull September morning, surveyed her stock for the first time without a smile on her face.

In her hand she held a newspaper. She had read it on the trolley, and what she read had sickened her. For the paper told of the things which Germany was doing on the other side of the water, and which had nothing to do with dolls or tin tracks or lead soldiers. But they had to do with real soldiers and with big guns and with death and destruction. For Germany, it seemed, was at war with all the world, and Germany was to blame.

At least, it looked that way to Dorothea. It had always seemed to her before that the toys had welcomed her. To people without imagination, toys are inanimate things, but to Dorothea they were as alive as the people who bought them. She never sold a pussy-cat without hoping that it would get a good home; she never parted with a wistful bisque baby without some anxiety as to the kind of mother it was to acquire. And as for her white elephants, she always saw them go with a heavy heart, fearing that their almost pathetic mildness might place them at the mercy of some boyish tyrant.

There was only one white elephant left and there would be no others. Making toys was one of the arts of peace, and Germany was at war!

Dorothea pulled up the shades of the big window. Every morning she set forth in that window the toys which were to act as a lure for the public eye. Even in these early fall days there were those who, passing through on their way from north-shore resorts, patronized the little place which was noted for its uniqueness.

It was quite the usual thing for Dorothea to give her white elephant the place of honor in the window. But this morning she would have none of him. The lead soldiers seemed to offer themselves obtrusively. The Prussian troops positively swaggered as Dorothea turned a stern eye upon them. For a moment she surveyed them, then she shut the cover of the box tightly, hiding the spectacle of their triumphant insolence.

She put some books in the window, and a row of Kewpie post-cards. These, with a few boxes of letter-paper and some half-dozen tubes of library paste, made a strictly American and neutral display. The books were published in Boston, the paper and paste were Middle West, and the Kewpies were irreproachably United States.

It was while she was giving the last touches to this somewhat sombre display that a man opened the door and entered. He was a small man with an upstanding halo of gray hair. But he was not old. Like Dorothea, his hair was older than his face, and his face was older than his heart. He limped a little, and in his hand he, too, carried a newspaper,

"Dear lady," he said, "good morning."

Dorothea turned and faced him. "It is not good morning, Herr von Puttkamer, it is bad morning. What do you think of your country now?"

"It is my country."

"And you still defend it?"

"It needs no defense."

"Not for this last awful thing?"

"War always brings awful things."

"But not such things as this—the shooting of non-combatants—of women and of children"

He was very pale. "These things are not proved." Then, softly: "Dear lady, are we to quarrel over this?"

She had been all ready to quarrel with him. Yet he was her friend. He had a little studio over the Toy Shop. He gave lessons in German and he did some translating.

Their friendship had begun when she had carried up to him a letter from a firm in Nuremberg. He had helped her with that, and had since helped her with others. Now and then, on dull days when customers were few, he would come down and sit in her little shop and talk to her. It was then that she learned of his younger brother, Franz. Franz was in the German army, and was big and blond and beautiful. When Otto spoke of him, it was as one speaks of one's beloved.

As their friendship had progressed, they had walked together in the summer evenings, in the Public Gardens and across the Common. They had even taken a few adventuring rides in the swan-boats. They had come back to the shop quite late after one of these rides, and Dorothea had made coffee in her little electric percolator. At another time they had gone down to Marblehead, and had had lobster sandwiches at the Pirate House, and had looked at the sea by moonlight.

The memory of these things stopped the words which cried for expression. Dorothea was of New England, and prone to say the things which were on her mind. But the soft voice of the little man was again protesting: "Dear lady, surely we are not to quarrel."

"I don't want to quarrel," Dorothea told him, "but how can I help it when you defend this dreadful unnecessary thing? Why, every time I look at my toys I think: 'There won't be any more. There won't be any more lead soldiers or lovely dolls or white elephants.'"

Otto laid his hand on the head of the meek white beast. "So, my friend," he said quietly, "it is you and I who are to blame, because we are of the—Fatherland, and presently she will sell you, and quarrel with me, and then?"

"I shall never sell him," Dorothea flared. "I shall keep him always as a monument to the folly of your country."

And now the fire in her seemed to light some fire in him. "It is not folly, but a woman cannot understand these things."

He could have said nothing worse. As I have said, Dorothea Dwight was of New England. In spite of the modishness of her blue-serge frock, in spite of the French twist to her hair and the silk-stockinged slenderness of her feet, she was the product of a civilization which sets women side by side with men mentally. The point of view of Otto von Puttkamer seemed to her as mediæval as the war which his country was waging.

"I understand this," she flung back at him, " that a few weeks ago you said that the women of England because they destroyed a few pictures and threw a few bombs were too hysterical to rule; yet your Kaiser, your generals, the men of your country, have burned libraries, and this morning there's the cathedral"

"There were signalmen in the towers"

"It is useless to argue"—her cheeks were flaming—"the whole thing is of the Middle Ages. It is cruel, cowardly. I'm sorry to say it, but I must, because I believe it, and there isn't any use in being hypocritical about it, is there?"

"No," he said, "no. But there is tragedy in this—that you should say these things—to me."

He turned toward the door, and it was not until he had crossed the threshold that Dorothea called him back. "Please," she said, "I'm sorry"

But her apology came too late. He stood quite stiffly and formally beyond the door, and said: "Good-by."

II

Mary Barnes, who helped in the shop, arriving late and breathless, was swept by Dorothea into a perfect vortex of house-cleaning.

"We might as well do it this morning, Mary," Dorothea said. "I can't get my mind down to anything else."

It was noon before Dorothea finished her housewifely task. Everything glittered and shone. The dolls in the cases smiled through the clear, clean glass. A row of pussy-cats on the counter seemed positively to purr with contentment.

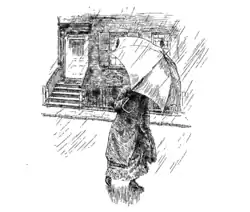

But Dorothea did not partake of the general effulgence. She was nervous and tired. It was raining, and as she stood by the window looking out on the sodden streets, she was conscious of her deep depression. She knew that she had hurt and offended Otto von Puttkamer, and he was the very best friend that she had in the whole wide world. To be sure, she had other friends, nice staid people whom she had always known, and whose mothers and fathers had known her mother and father, and whose grandfathers and grandmothers had known her grandfathers and grandmothers, and so on, down to the early days of the Massachusetts colony when everybody had known everybody else.

It was these friends who conceded to her, her proper place as a competent business woman and as a brainy one, and who invited her to dine with them on Thanksgiving, and to sup with them on Sundays, and who sent her tickets to the play, and who took her to ride in their limousines, and who were altogether considerate and kind in a pleasant, middle-aged manner. But it was Otto who gave to friendship the effect of youth and romance. It was Otto who left flowers for her in the most unexpected places—a rose fresh and nodding from a keyhole, a bunch of violets on the bayonet of a tin soldier, the cart of the little gray donkey heaped high with crocuses, a spray of hyacinths adorning the brow of the white elephant.

And no one but Otto took her adventuring. No one but Otto knew how to play.

And she should miss her playmate!

In the midst of her doleful reflections, she was aware that there had come suddenly within the line of her vision a big umbrella. Beneath the umbrella she could see little feet and a held-up black skirt. The umbrella turned toward the shop, and was lost in the outer entrance-hall. The door of Dorothea's shop opened into this hall, and a stairway led above.

But it was not up the stairway that the umbrella was going, for suddenly the door of the shop opened and the umbrella came in, precipitately. It was revealed in that moment that the little feet belonged to a little old lady, who, dropping the umbrella, shut the door, turned, and peered through the ground glass.

Baffled by its opaqueness, she darted to the window.

"There," she said triumphantly, "I did not let myself meet him. He was coming down the stairs, and if I had met him, Mees Dwight, I might have been rude. I did not want to speak to him, for one should not be rude—if one can avoid! So when I saw him, I quite rushed in here quickly!"

She had rushed in so quickly that she was breathless. Dorothea was conscious that Otto von Puttkamer was passing the window. He glanced neither to the right nor to the left, but went on.

The little old lady was very small and very fragile. Her little lovely feet were matched by little lovely hands. She was in simple and almost severe black. But the lace scarf which protected her throat, the little flat black hat which framed the oval of her high-bred face, were worn with the air which belongs only to the women of France.

"I should not care to quarrel with him," she said, with a catch of her breath, "but this morning I have on my heart the great cathedral—" Her voice faltered and stopped.

"I know," Dorothea said. "Dear Madame Papin, I have just quarrelled with him myself."

Madame Papin sat down in the low chair which Dorothea had placed for her, and folded her little hands. "That is more serious," she said; "he loves you, chérie."

Dorothea flushed. "Please," she protested.

Madame Papin leaned forward. "I know you do not talk of these things, as we talk of them. You are waiting for him to tell you—when his eyes are telling it, and his voice, and there's no need for words"

"Oh, please!" Dorothea protested again. To her Puritan self-consciousness Madame Papin's Gallic frankness was appalling.

Madame Papin laughed. Her laugh was the trill of a bird. "We will not talk of it, then," she said; "but I shall think of it, deep in my heart, and I shall think how you can make up your quarrel."

"If we make this up, we shall quarrel again," Dorothea said. "Oh, Madame Papin, I would never have believed that I could hate any one as I hate the Germans."

The little lady shrugged. "They are beasts," she said calmly. Then she leaned forward and looked straight into the eyes of the meek white elephant, upon whose dangling tag was blazoned forth the damning device—"Made in Germany."

"I hate you!" said little Madame Papin to the white elephant.

III

"All the things in my window this morning were made in America," Dorothea said. "It may seem silly, but I couldn't help it."

"And now you will have my little boxes to show," cried Madame Papin, "and the dinner-cards with the little roses."

Everything that Madame Papin painted had little roses, blushing on little china dishes, budding on little china boxes, wreathed on dinner-cards, rioting on bowls and vases and perfume bottles.

"I've lots of orders for you," Dorothea said as Madame Papin opened her bag and brought forth her rosy treasures; "it will keep you busy until Christmas, madame."

"I want to be busy," said the little lady. "It is hard work which keeps the heart from aching. Dear Mees Dwight, there are four nephews fighting in France. I am afraid to look at the papers—I am—I am afraid."

And this was war which made women afraid! Dorothea's hand went across the counter to clasp that of the little old lady. And presently she said: "Dear Madame Papin, stay and have a cup of tea with me in my little office. Mary shall get us something to eat with it, and then I'll send her home and we can have a visit together."

And thus it happened that the window display was changed that afternoon, and it was changed by Madame Papin.

And now who so gay as the little French soldiers in the window! Line upon line, with flags flying, they seemed to march toward victory. And back of them were Madame Papin's rosy boxes, and rose-wreathed cards, with the Kewpies pushed quite into a corner, and the tubes of paste totally obscured!

With this accomplished, madame sat down to knit on gray wool scarfs for the Belgians, and again to discuss the sins of Dorothea's neighbor.

"It was a week ago," she related with a sort of quivering indignation, "a week ago I met him, Mees Dwight, when I was coming in here with the dinner-cards, and we spoke of the war. I did not want to speak of the war. But he said, most politely: 'Ah, madame, it grieves me that your country and mine should be at war.' And I said: 'Monsieur, my heart weeps for France, as yours weeps for Germany.' And he said: 'Yes, our hearts weep,' and then, as we walked on together, I said, quite with innocence: 'And my heart weeps for the poor Belgians.' Then he spoke with such sharpness, Mees Dwight: 'But, madame, the Belgians were so obstinate.' I gave him just one little look and I left him, and since then I have not cared to speak to him. Would you call it obstinate, Mees Dwight, if some one came to you and said: 'Give me your white elephant and your lead soldiers and your little pussycats'? You would say: 'They are mine—you are a robber.' And now it is Germany that robs. If I had met Herr von Puttkamer this morning I might have told him—that"

Outside, the wet pavements, illumined by the street lamps, glimmered in a golden mist. Dorothea had not lighted the little shop. On an afternoon of rain there would be no customers. The toys were shadow shapes in the dusk. Dorothea dropped down on the stool which she had placed for Madame Papin's little feet.

"Madame," she said, "there was Waterloo, you know, and you hated the English"

"They were our enemies."

"And now you hate the Germans."

"They are our enemies."

The little lady's needles clicked in the ensuing silence. Dorothea's brain was busy. She had been nourished, as it were, in childhood on stories of the tea which had been tumbled into Boston harbor; on the midnight ride, the lights in the old North Church, and the embattled farmers. She had been saturated with pride at the part which Massachusetts had played in the struggle for independence.

In that struggle England had been wrong, dead wrong. And as for France, had there ever been any war-madness to equal the war-madness of Napoleon! Should Germany stand alone among the nations in the scarlet of military sins? And of Herr von Puttkamer was there not this to be said: that he would have been less of a man if he had not loved his country?

She rose and moved restlessly about the shop, and presently she set a music-box playing. It tinkled out, quite consistently, a little tune from "The Magic Flute."

"There," said Madame Papin, "even the music is their music"

"Herr von Puttkamer says," Dorothea stated, "that the music of his country, the literature, should show us that they would not fight for an unjust cause. He says that for this if for nothing else we should love Germany."

"Mon Dieu!" said the little lady from among the shadows. "Mon Dieu! Herr von Puttkamer is like the little lead soldiers, he was made in Germany. And when he speaks of love, he is thinking of you."

Dorothea, flushing, turned on the light, and went to the door to answer the postman's knock. Outside on the hall table a letter had been left for Otto von Puttkamer. It was a big letter with a foreign postmark and with an official look.

As Dorothea shut the door, Madame Papin cried: "Come quickly—Herr von Puttkamer this minute passed the window."

And now they heard his step in the hall.

"If he comes in here," said the sparkling little lady, "if he comes in here, Mees Dwight, my little French soldiers shall shoot him!"

They heard his slow steps going up the stairs, and presently they heard him coming down again. The door opened!

Their enemy was upon them!

This was no triumphant enemy, but an enemy agonized and pale. In his hand he held the letter with the official stamp.

He did not seem to see Madame Papin. His eyes were seeking Dorothea's. "I could not bear it alone," he said brokenly. "Dear lady, my brother—mein Brüderchen!"

O little lead soldiers, be glad that you have no hearts to break! O meek white elephant, be glad that your head is stuffed with sawdust, so that you have no mind to meditate on this monstrous murderous thing: War!

The hands of Madame Papin were very still. Her eyes were deep wells of tears. But Dorothea felt suddenly that here was something too deep for tears.

"Dear lady," Otto was saying, "surely you cannot hate me—now."

She went toward him swiftly, her hand outheld.

"It is—your country," she said softly. "Right or wrong—it is your country."

He took her hands in his and bent his face upon them, while all the little things which had been made in Germany stared at the man who had given to Germany the thing that, next to this woman who stood with her hands in his, he loved more than anything else in the whole wide world.

And now it was Madame Papin who broke the silence. She rose from her chair and touched Otto on the arm. He raised his head and looked down at her.

"Listen," she said with great earnestness; "listen, my friend. She will comfort you. She loves you. And where death is—there are no—enemies."

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1953, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 60 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.