CHAPTER IX

WHEN H. M. S. PHOENIX DROVE ASHORE

Where Blake and mighty Nelson fell

Your manly hearts shall glow,

As ye sweep through the deep,

While the stormy winds do blow!

While the battle rages loud and long

And the stormy winds do blow.

IT was a British admiral, Sir Lewis Bayly, who told the officers of the American destroyers operating out of Queenstown, "To work with you is a pleasure, to know you is to know the best traits of the Anglo-Saxon race." In the same spirit it is generous to recall the enduring traditions of the English Navy, which were welded through many centuries of courageous conflict with the sea and the enemy. The wooden frigates and the towering ships of the line gave place to the steel-walled cruiser and the grim, squat dreadnought, but for the men behind the guns the salty lineage was unbroken. As Beatty and his squadrons kept watch and ward in the misty Orkneys, so had Nelson maintained his uneasy vigil off Toulon.

Among the annals of the vanished days of the old navies, of the tarry, pigtailed seamen with hearts of oak, the story of a shipwreck has been preserved in a letter written to his mother by a lieutenant of the frigate Phoenix in the year 1780. He tells her about the tragic episode as though he had actually enjoyed it, scribbling the details with a boyish gusto which conveys to us, in a manner exceedingly vivid, how ships and men lived and toiled in the age of boarding-pikes, hammock-nettings, and single topsails. Few young men write such long letters to their mothers nowadays, and even in that era of leisurely and literary correspondence a friend who was permitted to read the narrative was moved to comment:

"Every circumstance is detailed with feeling and powerful appeals are continually made to the heart. It must likewise afford considerable pleasure to observe the devout heart of a seaman frequently bursting forth and imparting sublimity to the relation."

This stilted admiration must not frighten the modern reader away, for Lieutenant Archer held his old-fashioned piety well under control, and was as brisk, slangy, and engaging a young officer as you could find afloat in a skittish destroyer of the present day. The forty-four-gun frigate Phoenix was commanded by Captain Sir Hyde Parker, who later became an admiral, and under whose orders Nelson served for a time. His name has a flavor of interest for Americans because he took part in the British naval attack on New York in 1776 and later joined in harassing Savannah. With almost no naval strength in the War of the Revolution, the United States had only its audacious privateers to molest the enemy's commerce and was helpless to convoy or protect its merchant shipping, which was largely destroyed. The British squadron to which the Phoenix was attached, finding little American booty afloat in 1780, turned its attention to the Spanish foe and cruised in the waters of the Caribbean.

On August 2d the frigate sailed from Port Royal, Jamaica, escorting two store-ships to Pensacola, and then loafed about in the Gulf and off the Cuban coast for six weeks in quest of Spanish prizes. It was a hot, wretchedly uncomfortable business, this beating about in the tropics in a ship of a hundred and forty years ago. The bluejackets were frequently flogged by way of making them fond of the service, and many of them had been hauled into this kind of maritime slavery by the brutal press-gangs which raked the English ports. Somehow they managed to survive the chronic hardships of life at sea and to keep their ardor bright, so that in a gale of wind or against a hostile fleet they stubbornly did their duty as long as two planks held together. The bulldog strain made them heroic.

In the ward-room of the Phoenix, where the officers perspired and grumbled and cursed their luck, they kept an ingenious lottery going to vary the monotony of an empty sea. Every man put a Spanish dollar into a canvas bag and set down his guess of the date of sighting a sail. No two gamblers were to name the same date. Whenever a man lost, he dropped another dollar into the bag. It was growing heavy, for one week stretched into another without a gleam of royals or topgallant-sails from Vera Cruz to Havana. Like a good sportsman. Captain Sir Hyde Parker paid his stake into the dollar bag and squinted through his long brass spy-glass as he grumpily trudged the quarterdeck.

It was off Cape San Antonio, at the western end of Cuba, that the man at the masthead shouted down:

"A sail upon the weather bow."

"Ha! ha! Mr. Spaniard, I think we have you at last," jubilantly exclaimed the captain. "Turn out all hands! Make sail! All hands give chase!"

A midshipman scrambled aloft and blithely reported:

"A large ship standing athwart us and running right before the wind."

"Larboard! Keep her away! Set the studding-sails!" was the order, and two hundred nimble seamen raced to their stations on deck and in the tops and swarmed out along the yards.

Up from below came the little doctor, rubbing his hands and crying:

"What, ho! I have won the dollar bag!"

"The devil take you and your bag!" roared Lieutenant Archer. "Look yonder! That will fill all our money-bags."

"Two more sail on the larboard beam," came from aloft. "A whole fleet of twenty sail coming before the wind."

"Confound the luck of it!" growled the captain of the frigate, "this is some convoy or other; but we must try to snap up two or three of them. Haul in the studding-sails. Luff her. Let us see what we can make of them."

They were discovered to be twenty-five sail of Spanish merchantmen, under convoy of three lofty line-of-battle ships, one of which set out in chase of the agile Phoenix, which soon showed her heels. A frigate had no business to linger too close to the hundred guns of a ponderous three-decker. The huge Spanish man-of-war lumbered back to the convoy and herded them watchfully while the British nosed about until dark, but found no stray prizes that could be cut out from the flock. In the starlight three ships seemed to be steering a course at some distance from the Spanish fleet, so the frigate gave chase, and came up with a heavy vessel mounting twenty-six guns.

"Archer, every man to his quarters," said the captain. "Light the battle-lanterns and open the gun-ports. Show this fellow our force, and it may prevent his firing into us and killing a man or two."

Across the intervening water rang the challenge from the Phoenix:

"Ho, the ship ahoy! Lower your sails and bring to instantly, or I will sink you."

Amid the clatter of blocks and creaking of spars the other ship laid her mainyard aback and hung plunging in the wind while to the sharp interrogation her skipper bawled through his trumpet:

"This is the British armed merchant ship Polly, from Jamaica to New York. What ship are you?"

"His Majesty's forty-four gun frigate Phoenix," was the reply, at which the honest sailors of the merchantman let go three rousing cheers; but a glum old shell-back of the frigate's crew was heard to mutter:

"Oh, damn your huzzas! We took you to be something else."

The Polly had fallen in with the Spanish fleet that same morning, as it turned out, and had been chased all day, wherefore the frigate stood by her until they had run clear of danger. It was the courtesy of the sea, but Lieutenant Archer was unconsoled and he fretfully jotted down in writing to his mother:

"There I was, from being worth thousands in imagination, reduced to the old four and sixpence a day. The little doctor won the most prize money of us all, for the bag contained between thirty and forty dollars."

After almost running ashore in a thick night and clawing off by good seamanship, the Phoenix ran over to Jamaica for fresh water, and then sailed in company with two other frigates. The verdant mountains of that lovely island were still visible when the sky became overcast. By eleven o'clock that night, "it began to snuffle, with a monstrous heavy appearance from the eastward." Sir Hyde Parker sent for Lieutenant Archer, who was his navigating officer, and exclaimed:

"What sort of weather have we? It blows a little and has a very ugly look. If in any other quarter but this I should say we were going to have a smart gale of wind."

"Aye, sir," replied the lieutenant, "it looks so very often here when there is no wind at all. However, don't hoist topsails until it clears a little."

Next morning it was dirty weather, blowing hard, with heavy squalls, and the frigate laboring under close-reefed lower sails.

"I doubt whether it clears," said the frowning captain. "I was once in a hurricane in the East Indies, and the beginning of it had much the same appearance as this. So be sure we have plenty of sea room."

All day the wind steadily increased in violence, and the frigate, spray-swept and streaming, rolled in the passage between Jamaica and Cuba, in peril of foundering if she stayed at sea and of fetching up on the rocks if she tried to run for shelter. There was nothing to do but to fight it out. I shall let Lieutenant Archer describe something of the struggle in his own words, old sea lingo and all, because he depicts it with a spirit so high-hearted and adventurous, quite as you would expect it of a true-blue young sailorman.

At ten o'clock I thought to get a little sleep; came to look into my cot; it was full of water, for every seam, by the straining of the ship had begun to leak and the sea was also flooding through the closed gun-ports. I stretched myself, therefore, upon the deck between two chests and left orders to be called, should the least thing happen. At twelve a midshipman came up to me:

"Mr. Archer, we are just going to wear ship, sir."

"Oh, very well, I '11 be up directly. What sort of weather have you got?"

"It blows a hurricane, sir, and I think we shall lose the ship."

Went upon deck and found Sir Hyde there. Said he:

"It blows damned hard, Archer."

"It does indeed, sir."

"I don't know that I ever remember it blowing so hard before, Archer, but the ship makes a very good weather of it upon this tack as she bows the sea; but we must wear her, as the wind has shifted to the south-east and we are drawing right down upon Cuba. So do you go forward and have some hands stand by; loose the lee yard-arm of the foresail and when she is right before the wind, whip the clew-garnet close up and roll up the sail."

"Sir, there is no canvas that can stand against this a moment. If we attempt to loose him he will fly into ribands in an instant, and we lose three or four of our people. She will wear by manning the fore shrouds."

"No, I don't think she will, Archer."

"I 'll answer for it, sir. I have seen it tried several times on the coast of America with success."The captain accepted the suggestion, and Archer considered it "a great condescension from such a man as Sir Hyde." Two hundred sailors were ordered to climb into the fore-rigging and flatten themselves against the shrouds and ratlines where the wind tore at them and almost plucked them from their desperate station. Thus arranged, their bodies en masse made a sort of human sail against which the hurricane exerted pressure enough to swing the bow of the struggling ship, and she very slowly wore, or changed direction until she stood on the other tack. It was a feat of seamanship which was later displayed during the historic hurricane in the harbor of Samoa when British, German, and American men-of-war were smashed by the tremendous fury of wind and sea, and the gallant old steam frigates Vandalia, Trenton, and Nipsic faced destruction of the Stars and Stripes gallantly streaming and the crews cheering the luckier British ship that was able to fight its way out to sea.

The hapless Phoenix endured it tenaciously, but the odds were too great for her. When she tried to rise and shake her decks free of the gigantic combers, they smashed her with incessant blows. The stout sails were flying out of the gaskets that bound them to the yards. The staunch wooden hull was opening like a basket. The ship was literally being pounded to pieces. Sir Hyde Parker, lashed near the kicking wheel, where four brawny quartermasters sweated as they endeavored to steer the dying frigate, was heard to shout:

"My God! To think that the wind could have such force!"

There was a terrific racket below decks, and fearing that one of the guns might have broken adrift from its tackles, Lieutenant Archer clambered into the gloomy depths, where a marine officer hailed him, announcing:

"Mr. Archer, we are sinking. The water is up to the bottom of my cot. All the cabins are awash and the people flooded out."

"Pooh! pooh!" was the cheery answer, "as long as it is not over your mouth you are well off. What the devil are you making all this noise about?"

The unterrified Archer found much water between decks, "but nothing to be alarmed at," and he told the watch below to turn to at the pumps, shouting at them:

"Come pump away, my lads! Will you twiddle your thumbs while she drowns the lot of you? Carpenters, get the weather chain-pump rigged."

"Already, sir."

"Then man it, and keep both pumps going. The ship is so distressed that she merely comes up for air now and then. Everything is swept clean but the quarterdeck."

Presently one of the pumps choked, and the water gained in the hold, but soon the bluejackets were swinging at the brakes again, while Lieutenant Archer stood by and cheered them on. A carpenter's mate came running up to him with a face as long as his arm and shouted:

"Oh, sir, the ship has sprung a leak in the gunner's room."

"Go, then, and tell the carpenter to come to me, but don't say a word about it to any one else."

When the carpenter came tumbling aft he was told:

"Sir, there is nothing there," announced the trusty carpenter, a few minutes later. "‘T is only the water washing up between the timbers that this booby has taken for a leak."

"Oh, very well, go upon deck and see if you can keep the water from washing down below."

"Sir, I have four people constantly keeping the hatchways secure, but there is such a weight of water upon the deck that nobody can stand it when the ship rolls."Just then the gunner appeared to add his bit of news.

"I thought some confounded thing was the matter, and ran directly," wrote Lieutenant Archer.

" Well, what is the trouble here?"

"The ground tier of powder is spoiled," lamented the faithful gunner, "and I want to show you, sir, that it is not because of any carelessness of mine in stowing it, for no powder in the world could be better stowed. Now, sir, what am I to do? If you don't speak to Sir Hyde in my behalf, he will be angry with me."

Archer smiled to see how easily the gunner took the grave danger of the ship and replied:

"Let us shake off this gale of wind first and talk of the damaged powder later."

At the end of his watch below, Archer thought that the toiling gangs at the pumps had gained on the water a little. When he returned to the deck

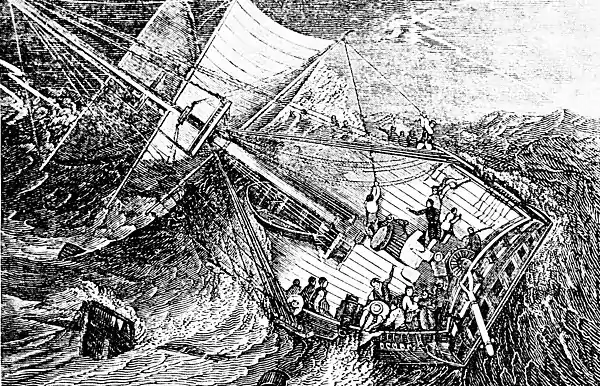

PERILOUS SITUATION OF THE SHIP

"I am not in the least afraid of that," said the captain. "I have commanded her for six years and have had many a gale of wind in her, so that her iron work, which always gives way first, is pretty well tried. Hold fast, Archer, that was an ugly sea. We must lower the yards, for the ship is much pressed."

"If we attempt it, sir, we shall lose them, for a man aloft can do nothing; besides, their being down would ease the ship very little; the mainmast is a sprung mast; I wish it were overboard without carrying everything with it, but that can soon be done. The gale cannot last forever. 'T will soon be daylight now."

Found by the master's watch that it was five o'clock, glad it was so near dawn and looked for it with much anxiety. Cuba, thou are much in our way! Sent a midshipman to fetch news from the pumps. The ship was filling with water despite all their labor. The sea broke halfway up the quarterdeck, filled one of the cutters upon the booms and tore her all to fragments. The ship lying almost upon her beam ends and not attempting to right again. Word from below that the water had gained so fast they could no longer stand to the pumps. I said to Sir Hyde:

"This is no time, sir, to think of saving the masts. Shall we cut away?"

"Aye, Archer, as fast as you can."

I accordingly went into the chains with a pole-axe to cut away the lanyards; the boatswain went to leeward, and the carpenters stood by the mast. We were already when a very violent sea broke right on board of us, carried away everything that was left on deck, filled the ship with water, the main and mizzen-masts went, the ship righted but was in the last struggle of sinking under us. As soon as we could shake our heads above water Sir Hyde exclaimed:

"We are gone at last, Archer,—foundered at sea."

"Yes, sir. And the Lord have mercy upon us."The unlucky crew of the Phoenix frigate, more than three hundred souls, had behaved with disciplined fortitude. The captain, who had commanded her for six years, knew his ship and her people, and they had stood the test. In this weltering chaos of wind and sea, which extended far over the Caribbean, twelve other ships went down, all of them flying the white ensign of the Royal Navy, and more than three thousand seamen perished. Maritime disasters were apt to occur on a tremendous scale in those olden days when ships sailed in fleets and convoys.

It was not ordained that the brave and dogged ship's company of the Phoenix should be entirely swallowed by the sea. While they fought the last fight for life in the broken, sinking hulk, the keel thumped and ground along the back of a reef. Lieutenant Archer and Captain Sir Hyde Parker were floundering about together and had given themselves up for lost. The lieutenant was filled with reflections profoundly religious, as well as with salt water, and he took pains to expound them at length in writing to his mother, and these were a great solace, no doubt, to the good woman who waited for infrequent tidings in a home of green England. Sir Hyde Parker was swearing and spluttering at his men who were crying, "Lord have mercy on us!"

"Keep to the quarter-deck, my boys, when she goes to pieces," he yelled. "’T is your best chance."

The shattered remnants of the frigate were being flailed upon the Cuban reef, but the boatswain and the carpenter rallied volunteers who cut away the foremast, which dragged five men to their death when it fell. All this was in the black, bewildering darkness just before the stormy day began to break; but the crew held on until they were able to see the cruel ledges and the mountainous coast which was only a few hundred feet away. Lieutenant Archer was ready to undertake the perilous task of trying to swim ashore with a line, but after he had kicked off his coat and shoes he said to himself:

This won't do, for me to be the first man out of the ship, and the senior lieutenant at that. We may get to England again and people may think I paid a great deal of attention to myself and not much to anybody else. No, that won't do; instead of being the first, I 'll see every man, sick and well, out of her before me.

Two sailors managed to fetch the shore, and a hawser was rigged by means of which all of the survivors succeeded in reaching the beach. True to his word. Archer was the last man to quit the wreck. Sir Hyde Parker was a man of more emotion than one might infer, and the scene is appealing as the lieutenant describes it.

The captain came to me, and taking me by the hand was so affected that he was scarcely able to speak. "Archer, I am happy beyond expression, to see you on shore but look at our poor Phoenix." I turned about but could not say a single word; my mind had been too intensely occupied before; but everything now rushed upon me at once, so that I could not contain myself, and I indulged for a full quarter of an hour in tears.

The resourceful bluejackets first entrenched themselves and saved what arms they could find in the ship, for this was no friendly and hospitable coast. They were on Spanish soil, and it was not their desire to be marched off to the dungeons of Havana as prisoners of war. Tents and huts were speedily contrived, provisions rafted from the wreck, fires built, fish caught, and the camp was a going concern in two or three days. Archer proposed that the handy carpenters mend one of the boats and that he pick a crew to sail to Jamaica and find rescue. This was promptly done and he says:

In two days she was ready and I embarked with four volunteers and a fortnight's provisions, hoisted English colors as we put off from the shore and received three cheers from the lads left behind, having not the least doubt that, with God's assistance, we should come and bring them all off. Had a very squally night and a very leaky boat so as to keep two buckets constantly baling. Steered her myself the whole night by the stars and in the morning saw the coast of Jamaica distant twelve leagues. At eight in the evening arrived at Montego Bay.

This dashing lieutenant was not one to let the grass grow under his feet, and he sent a messenger to the British admiral, another to the man-of-war, Porcupine, and hustled off to find vessels on his own account. All the frigates of the station were at sea, but Archer commandeered three fishing craft and a little trading brig and put to sea with his squadron. Four days after he had left his shipwrecked comrades he was back again, and they hoisted him upon their shoulders and so lugged him up to Sir Hyde Parker's tent as the hero of the occasion. The Porcupine arrived a little later, so there was plenty of help for the marooned British tars. Two hundred and fifty of them were carried to Jamaica. Of the others "some had died of the wounds they received in getting on shore, some of drinking rum, and a few had straggled off into the country."

Lieutenant Archer was officially commended for the part he had played, and was promoted to command the frigate Tobago after a few months of duty on the admiral's staff. You will like to hear, I am sure, how he wound up the long letter home which contained the story of the last cruise of the Phoenix.