CHAPTER XV

THE BRISK YARN OF THE SPEEDWELL PRIVATEER

CAPTAIN GEORGE SHELVOCKE was one of many seamen adventurers unknown to fame who sought a quick and bloody road to fortune by laying violent hands on the golden ingots in the Spanish galleons of Mexico and Peru. A state of war made this a lawful pastime for lawless men, and such were those that sailed from Plymouth on February 13, 1720, in the little armed ship Speedwell, bound out from England to South America with a privateering commission. She was of two hundred tons burden, and there could have been no room to swing a cat by the tail, what with eighteen six-pounders mounted between-decks, a fourteen-oar launch stowed beneath the hatches, provisions for a long voyage, and a crew of a hundred men. Most of these were landlubbers, wastrels of the taverns and the waterside, who were so terrified by the first gale of wind that seventy of them "were resolved on bearing away for England to make a complaint against the ship. They alleged that she was so very crank that she would never be able to encounter a voyage to the South Seas."

The fact that the seventy objectors were unanimously seasick delayed the mutiny; besides which, Captain Shelvocke talked to them, and he was a persuasive man whenever he used a pair of flintlock pistols to make his meaning clear. With calmer weather the seventy recalcitrants plucked up spirit to renew the argument, and went so far as to seize the helm and trim the yards on a course toward England. The captain was now seriously vexed. With a dozen officers behind him, he overruled the majority, tied two of them in the rigging, and ordered them handsomely flogged, and consented to forgive the others on promise of good behavior. "Nevertheless," remarks a commentator, "it occasioned him great uneasiness to find himself with a ship's company likely to occasion such trouble and vexation."

The Speedwell almost foundered before she was a fortnight at sea, the pumps going, crew praying, and some of her provisions and gunpowder spoiled by salt water; but Captain George Shelvocke shoved her along for the South Sea, half a world away, and set it down as all in the day's work. Sea-faring in the early eighteenth century was not a vocation for children or weaklings.

Seeking harbor on the coast of Brazil to obtain wood and water, the Speedwell fell in with a French man-of-war whose commander and officers were invited aboard the privateer for dinner. The crew was inconsiderate enough to touch off another mutiny, which interrupted the pleasant party; but the French guests gallantly sailed into the ruction, and their swords assisted in restoring order, after which dinner was finished. Captain Shelvocke apologized for the behavior of his crew, and explained that "it was the source of melancholy reflection that he, who had been an officer thirty years in the service should now be continually harassed by the mutiny of turbulent people." Most of them were for deserting, but he rounded them up ashore and clubbed them into the boats, and the Speedwell sailed to dare the Cape Horn passage.

For two long months she was beating off Terra del Fuego and fighting her way into the Pacific, spars and rigging sheathed in ice, the landlubbers benumbed and useless, decks swept by the Cape Horn combers; but Captain George Shelvocke had never a thought in his head of putting back and quitting the golden adventure. He finally made the coast of Chile, at the island of Chiloé, and when the Spanish governor of the little settlement refused to sell him provisions, he went ashore and

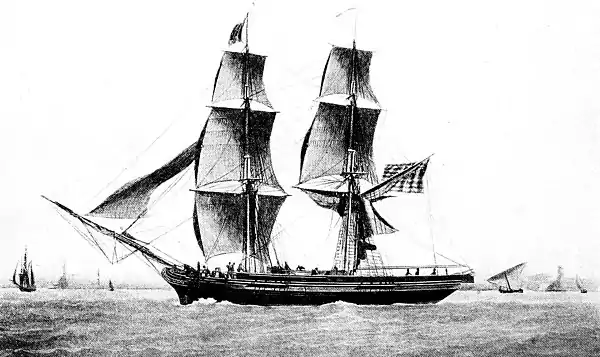

THE BRIG "OLINDA," OF SALEM, BUILT IN 1825

From the by original by François Roux of Marseilles, in the Marine Room, Peabody Museum, Salem.

The Speedwell next captured the town of Payta and put the torch to it after the governor had refused to contribute ten thousand pieces of eight. While the crew was ashore, a heavily armed ship came sailing in, and the flag at her yard proclaimed that a Spanish admiral was in command. In the privateer were left only the sailing-master, Mr. Coldsea, and nine men; but they served the guns with so much energy that the admiral cleared for action and reckoned he had met up with a tough antagonist. While they were banging away at each other. Captain Shelvocke was hustling his men into the boats and pulling off from shore; but before they had reached their own ship, the Spanish admiral had ranged within pistol-shot and was letting go his broadside. The situation was ticklish in the extreme, but the narrative explains it quite calmly:

Captain Shelvocke then cut his cable, when the ship falling the wrong way, he could just clear the admiral; but there was a great damp cast on the spirits of his people, at seeing a ship mounting fifty-six guns, with four hundred and twenty men, opposed to the Speedwell which had only twenty then mounted, with seventy-three white men and eleven negroes. Some of them in coming off, were for leaping into the water and swimming ashore, which one actually did.

Drifting under the admiral's lee, the Speedwell was becalmed for an hour, while the powder-smoke obscured them both, the guns flamed, and the round shot splintered the oak timbers. Captain Shelvocke's ensign was shot away, and the Spanish sailors swarmed upon their high forecastle and cheered as they made ready to board; but another British ensign soared aloft, and then a breeze drew the privateer clear, and she bore for the open sea. Her rigging was mostly shot away, there was a cannon-ball in the mainmast, the stern had been shattered, guns were dismounted, and the launch had been blown to match-wood by the explosion of a pile of powder-bags; but she clapped on sail somehow and ran away from the Spanish flag-ship, which came lumbering out after her.

The Speedwell was chased next day by another man-of-war, but dodged after nightfall by means of the expedient of setting a lighted lantern adrift in a tub and so deluding the enemy. It was the sensible conclusion of Captain Shelvocke that there might be better hunting on the coast of Mexico. South American waters seemed to be rather uncomfortable for gentlemen adventurers.

The privateer stood away for the island of Juan Fernandez to refit and rest her crew. They needed a respite by the time the island was sighted, for they were six weeks on the way, and the ship sprang a leak where a Spanish shot had lodged in her bow, and they pumped until they dropped in their tracks. Eleven years earlier Alexander Selkirk, who was the real Robinson Crusoe, had been rescued from his solitary exile on Juan Fernandez, where Captain Dampier's expedition had marooned him. With his garden and his flock of wild goats and his Holy Bible he had passed four years of an existence so satisfactory

So beneficial were the results that it might have improved the morals and the manners of Alexander Selkirk's shipmates if they had been marooned with him. This was the fate, indeed, which happened to the crew of the Speedwell. While they were filling the water-casks, a gale drove the ship hard ashore. The disaster came so suddenly that "their surprise at this unexpected event is not to be described; and in a very few minutes the ship was full of water and almost everything destroyed. All the people, however, except one man were saved."

As was to be expected. Captain George Shelvocke proceeded to make the best of it. He managed to raft ashore most of the gunpowder, some bread and beef, the nautical instruments and compasses, and was careful to see that his precious privateering commission was safely in his pocket. It will be inferred from this that he had no intention of letting so small a trifle as a shipwreck interfere with his plans of disturbing the peace of the viceroys of Spain. A little village of tents and huts was promptly built near a stream of fresh water, and when the castaways had sufficiently rested their weary bones, the captain called them together and announced that they would have to build a small vessel if they did not wish to spend the rest of their days on this desolate island. He was not one to be content with devotional exercises and a household of dancing goats and cats. His crew replied that they were anxious to build some sort of craft if he would show them how, and accordingly they pulled the wreck of the Speedwell apart and piled the timbers on the beach.

Keel-blocks were set up, and they began to put together what they called a bark. It was to be only forty feet long, with a depth of seven feet, by no means large enough to hold a hundred men, but material was difficult to obtain and skilled labor scarce. The armorer directed the work, being a man of skill and industry; but after two months of toil the fickle company tired of the job and sought entertainment in mutiny. Captain Shelvocke was a harsh, masterful person, so a conspiracy deposed him from the command, and a new set of articles was drawn up which organized a company of free adventurers who purposed to do things in their own way. They took possession of the muskets and pistols and wandered off inland to waste the ammunition in shooting goats.

The sight of a large Spanish ship in the offing put a check on this nonsense. If captured, they would certainly be hanged; so they flocked in to urge Captain Shelvocke to resume the command and prepare a scheme of defense. As soon as the hostile ship disappeared, however, they were brewing trouble afresh, one party voting to elect the first lieutenant as captain, another standing by Captain Shelvocke, and a third, perhaps a dozen in number, deciding to quit the crew and remain on the island. This group of deserters drifted away and built a camp of their own and were a good riddance. The captain got the upper hand of the rest, and the labor of finishing the tiny bark was taken up again.

When it came to planking the bottom, the only material was what could be ripped off the deck of the wrecked Speedwell. The stuff was so old and brittle that it split into small pieces, and great pains were required to fit it to the frames of the bark. Then the seams were calked as tight as possible, and water poured in to test them. Alas! there were leaks from stem to stern, and the discouraged seamen swore to one another that she was no better than a damned sieve. They were ready to abandon the enterprise, but Captain Shelvocke bullied and coaxed them into picking up their tools again.

They patched and calked and tinkered until it was agreed that the bark might possibly be kept afloat. The cooper made wooden buckets enough for every man to have one to bale with, and one of the ship's pumps was mended and fitted into the hold. Two masts were set up and rigged, canvas patched for sails, and a launching day set to catch the spring tide of October. Meanwhile the cooper was getting casks ready for provisions. These consisted of two thousand conger-eels which had been dried in smoke, seal-oil to fry them in, one cask of beef, five or six of flour, and half a dozen live hogs.

When they tried to launch the bark, the blocks gave way, and she fell upon her side and stuck fast. Again the faint-hearted seamen were for giving up the game as lost, but the competent armorer rigged purchases and tackles and lifted the craft, and she slid into the water on the next tide. Captain Shelvocke duly christening her the Recovery. For an anchor and cable they had to use a large stone and a light rope; so before she could drift ashore they stowed themselves aboard, leaving a dozen who preferred to live on Juan Fernandez and several negroes who could shift for themselves. There had been deaths enough to reduce the number of officers and men to fifty as the complement of the forty-foot bark, which ran up the British ensign and wallowed out into the wide Pacific.

It was then found that one pump constantly working would keep the vessel free. In distributing the provisions, one of the conger eels was allowed to each man in twenty-four hours, which was cooked on a fire made in a half tub filled with earth; and the water was sucked out of a cask by means of a musket barrel. The people on board were all uncomfortably crowded together and lying on the bundles of eels, and in this manner was the voyage resumed.

The plans of Captain George Shelvocke were direct and simple—to steer for the Bay of Concepción as the nearest port, in the hope of capturing some vessel larger and more comfortable than his own. In a moderate sea the bark "tumbled prodigiously," and all hands were very wet because the only deck above them was a grating covered with a tarpaulin; but the captain refused to bear away and ease her. At some distance from the South American coast a large ship was sighted in the moonlight. The desperate circumstances had worn the line between privateering and piracy very thin, but in the morning it was discovered that the ship was Spanish and therefore a proper prize of war. She did not like the looks of the little bark and its wild crew, and edged away with all canvas set. Captain Shelvocke crowded the Recovery in chase of her, and when it fell calm, his men swung at the oars.

The audacious bark had no battery of guns, mind you, for they had been left behind in the wreck of the Speedwell. One small cannon had been hoisted aboard, but the men were unable to mount it, and were therefore obliged to let it lie on deck and fire it, jumping clear of the recoil and hitching it fast with hawsers to prevent it from hopping over the side. For ammunition they had two round shot, a few chain-bolts and bolt-heads, the clapper of the Speedwell's brass bell, and some bags of stones which had been gathered on the beach. It appeared that they would have to carry the big Spanish ship by boarding her, if they could fetch close enough alongside, though they were also in a very bad way for small arms. A third of the muskets lacked flints, and there were only three cutlasses in the crew.

Captain Shelvocke ignored these odds, and held on after the ship until a four-hour chase brought him within a few hundred feet of her, so near that the Spanish sailors could be heard calling them English dogs and defying them to come on board. Along with the curses flew a volley of great and small shot, which killed the Recovery's gunner and almost carried away her foremast.

With several officers and men wounded, the errant little bark wandered northward, raiding the coast for provisions and riding out one gale after another, until another large ship was encountered. This was the stately merchantman, St. Francisco Palacio of seven hundred tons. By way of comparison. Captain Shelvocke estimated his bark as measuring about twenty tons. The Recovery rowed up to her in a calm and fought her for six hours, when the sea roughened, and there was no hope of closing in. It was a grievous disappointment, for the St. Francisco Palacio was so deeply laden with rich merchandise that as she rolled the water ran through her scuppers across the upper deck, and her poop towered like a wooden castle.

The second failure to take a prize made the unsteady crew discontented, and several of them stole the best boat and ran away with it. Mutiny was forestalled by an encounter with a Spanish vessel called the Jesus Maria in the roadstead of Pisco. Preparations were made to carry her by storm, as Captain Shelvocke concluded that she would suit his requirements very nicely and his bark was unfit to keep the sea any longer. The Recovery was jammed alongside after one blast of scrap-iron and other junk from the prostrate cannon, and the boarders tumbled over the bulwarks, armed with the three cutlasses and such muskets as could be fired. The Spanish captain and his officers had no stomach to resist such stubborn visitors as these. Doffing their hats, they bowed low and asked for quarter, which Captain Shelvocke was graciously pleased to grant. The Jesus Maria was found to be laden with pitch, tar, copper, and plank, and her captain offered to ransom her for sixteen thousand dollars.

Captain Shelvocke needed the ship more than he did the money, so he transferred his crew to the stout Jesus Maria and bundled the Spaniards into the Recovery and wished them the best of luck. The shipwreck at Juan Fernandez and all the other misfortunes were forgotten. The adventurers were in as good a ship as the lost Speedwell and needed only more guns to make a first-class fighting privateer of her. They now carried out the original intention of cruising to Mexico, and in those waters captured a larger ship, the Sacra Familia of six guns and seventy men. Again Captain Shelvocke shifted his flag and left the Jesus Maria to his prisoners. On board of his next capture, the Holy Sacrament, he placed a prize crew, but the Spanish sailors rose and killed all the Englishmen, and the number of those who had sailed from England in the Speedwell was now reduced to twenty-six.

Off the coast of California sickness raged among them until only six or seven sailors were fit for duty. Then Captain Shelvocke did the boldest thing of his career, sailing the Holy Sacrament all the way across the Pacific until he reached the China coast and found refuge in the harbor of Macao. Then this short-handed crew worked the battered ship to Canton, where the captains of the East Indiamen expressed their amazement at the ragged sails, the feeble, sea-worn men, and the voyage they had made. Captain George Shelvocke by this feat alone enrolled himself among the great navigators of the eighteenth century. He had found no Spanish galleons to plunder, and his adventure was a failure, but as a master of men and circumstances he had won a singular success.

He saw that his few men were safely embarked in an East Indiaman bound to London, and after a vacation in Canton he, too, went home as a passenger, completing a journey around the globe. Three and a half years had passed since he sailed from Plymouth in the Speedwell with a mutinous crew of landlubbers and high hopes of glittering fortune. Almost every officer had died, including the sailing-master, the first lieutenant, the gunner, the armorer, and the carpenter, and of the original company, a hundred strong, no more than a dozen saw England again. Nothing more is known of the seafaring career of Captain Shelvocke, but he was no man to idle on a quay or loaf in a tap-room, and it is safe to say that he lived other stories that would be vastly entertaining.