CHAPTER I

THE SINGULAR FATE OF THE BRIG P0LLY

"Oh, night and day the ships come in,

The ships both great and small.

But never one among them brings

A word of him at all.

From Port o' Spain and Trinidad,

From Rio or Funchal,

And along the coast of Barbary."

STEAM has not banished from the deep sea the ships that lift tall spires of canvas to win their way from port to port. The gleam of their topsails recalls the centuries in which men wrought with stubborn courage to fashion fabrics of wood and cordage that should survive the enmity of the implacable ocean and make the winds obedient. Their genius was unsung, their hard toil forgotten, but with each generation the sailing ship became nobler and more enduring, until it was a perfect thing. Its great days live in memory with a peculiar atmosphere of romance. Its humming shrouds were vibrant with the eternal call of the sea, and in a phantom fleet pass the towering East Indiaman, the hard-driven Atlantic packet, and the gracious clipper that fled before the Southern trades.

A hundred years ago every bay and inlet of the New England coast was building ships which fared bravely forth to the West Indies, to the roadsteads of Europe, to the mysterious havens of the Far East. They sailed in peril of pirate and privateer, and fought these rascals as sturdily as they battled with wicked weather. Coasts were unlighted, the seas uncharted, and navigation was mostly by guesswork, but these seamen were the flower of an American merchant marine whose deeds are heroic in the nation's story. Great hearts in little ships, they dared and suffered with simple, uncomplaining fortitude. Shipwreck was an incident, and to be adrift in lonely seas or cast upon a barbarous shore was sadly commonplace. They lived the stuff that made fiction after they were gone.

Your fancy may be able to picture the brig Polly as she steered down Boston harbor in December, 1811, bound out to Santa Cruz with lumber and salted provisions for the slaves of the sugar plantations. She was only a hundred and thirty tons burden and perhaps eighty feet long. Rather clumsy to look at and roughly built was the Polly as compared with the larger ships that brought home the China tea and silks to the warehouses of Salem. Such a vessel was a community venture. The blacksmith, the rigger, and the calker took their pay in shares, or "pieces." They became part owners, as did likewise the merchant who supplied stores and material; and when the brig was afloat, the master, the mate, and even the seamen were allowed cargo space for commodities that they might buy and sell to their own advantage. A voyage directly concerned a whole neighborhood.

Every coastwise village had a row of keel-blocks sloping to the tide. In winter weather too rough for fishing, when the farms lay idle, the Yankee Jack of all trades plied his axe and adz to shape the timbers and peg together such a little vessel as the Polly, in which to trade to London or Cadiz or the Windward Islands. Hampered by an unfriendly climate, hard put to it to grow sufficient food, with land immensely difficult to clear, the New-Englander was between the devil and the deep sea, and he sagaciously chose the latter. Elsewhere, in the early days, the forest was an enemy, to be destroyed with great pains. The pioneers of Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine regarded it with favor as the stuff with which to make stout ships and the straight masts they "stepped" in them.

Nowadays, such a little craft as the Polly would be rigged as a schooner. The brig is obsolete, along with the quaint array of scows, ketches, pinks, brigantines, and sloops which once filled the harbors and hove their hempen cables short to the clank of windlass or capstan-pawl, while the brisk seamen sang a chantey to help the work along. The Polly had yards on both masts, and it was a bitter task to lie out in a gale of wind and reef the unwieldy single topsails. She would try for no record passages, but jogged sedately, and snugged down when the weather threatened.

On this tragic voyage she carried a small crew. Captain W. L. Cazneau, a mate, four sailors, and a cook who was a native Indian. No mention is to be found of any ill omens that forecasted disaster, such as a black oat, or a cross-eyed Finn in the forecastle. Two passengers were on board, "Mr. J. S. Hunt and a negro girl nine years old." We know nothing whatever about Mr. Hunt, who may have been engaged in some trading "adventure" of his own. Perhaps his kinsfolk had waved him a fare-ye-well from the pier-head when the Polly warped out of her berth.

The lone piccaninny is more intriguing. She appeals to the imagination and inspires conjecture. Was she a waif of the slave traffic whom some benevolent merchant of Boston was sending to Santa Cruz to find a home beneath kindlier skies? Had she been entrusted to the care of Mr. Hunt? She is unexplained, a pitiful atom visible for an instant on the tide of human destiny. She amused the sailors, no doubt, and that austere, copper-hued cook may have unbent to give her a doughnut when she grinned at the galley-door.

Four days out from Boston, on December 15, the Polly had cleared the perilous sands of Cape Cod and the hidden shoals of the Georges. Mariners were profoundly grateful when they had safely worked offshore in the winter-time and were past Cape Cod, which bore a very evil repute in those days of square-rigged vessels. Captain Cazneau could recall that somber day of 1802 when three fine ships, the Ulysses, Brutus, and Volusia, sailing together from Salem for European ports, were wrecked next day on Cape Cod. The fate of those who were washed ashore alive was most melancholy. Several died of the cold, or were choked by the sand which covered them after they fell exhausted.

As in other regions where shipwrecks were common, some of the natives of Cape Cod regarded a ship on the beach as their rightful plunder. It was old Parson Lewis of Wellfleet, who, from his pulpit window, saw a vessel drive ashore on a stormy Sunday morning. "He closed his Bible, put on his outside garment, and descended from the pulpit, not explaining his intention until he was in the aisle, and then he cried out, 'Start fair' and took to his legs. The congregation understood and chased pell-mell after him."

The brig Polly laid her course to the southward and sailed into the safer, milder waters of the Gulf Stream. The skipper's load of anxiety was lightened. He had not been sighted and molested by the British men-of-war that cruised off Boston and New York to hold up Yankee merchantmen and impress stout seamen. This grievance was to flame in a righteous war only a few months later. Many a voyage was ruined, and ships had to limp back to port short-handed, because their best men had been kidnapped to serve in British ships. It was an age when might was right on the sea.

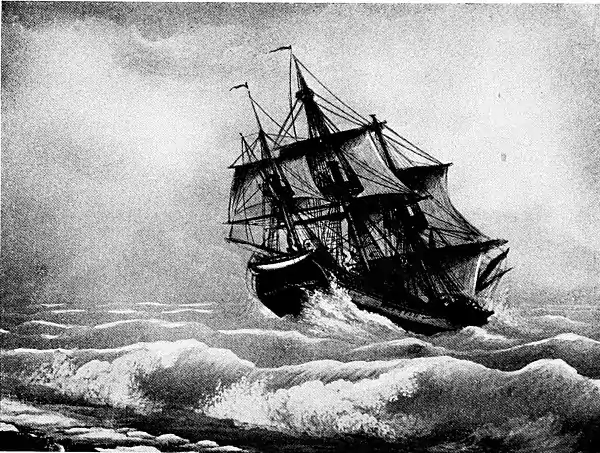

The storm which overwhelmed the brig Polly came out of the southeast, when she was less than a week on the road to Santa Cruz. To be dismasted and water-logged was no uncommon fate. It hapens often nowadays, when the little schooners creep along the coast, from Maine and Nova Scotia ports, and dare the winter blows to earn their bread.

SEAMANSHIP WAS HELPLESS TO WARD OFF THE ATTACK OF THE STORM THAT LEFT THE BRIG A SODDEN HULK

Seamanship was helpless to ward off the attack of the storm that left the brig a sodden hulk. Courageously her crew shortened sail and made all secure when the sea and sky presaged a change of weather. These were no green hands, but men seasoned by the continual hazards of their calling. The wild gale smote them in the darkness of night. They tried to heave the vessel to, but she was battered and wrenched without mercy. Stout canvas was whirled away in fragments. The seams of the hull opened as she labored, and six feet of water flooded the hold. Leaking like a sieve, the Polly would never see port again.

Worse was to befall her. At midnight she was capsized, or thrown on her beam-ends, as the sailor's lingo has it. She lay on her side while the clamorous seas washed clean over her. The skipper, the mate, the four seamen, and the cook somehow clung to the rigging and grimly refused to be drowned. They were of the old breed, "every hair a rope-yarn and every finger a fish-hook." They even managed to find an ax and grope their way to the shrouds in the faint hope that the brig might right if the masts went overside. They hacked away, and came up to breathe now and then, until foremast and mainmast fell with a crash, and the wreck rolled level. Then they slashed with their knives at the tangle of spars and ropes until they drifted clear. As the waves rush across a half-tide rock, so they broke over the shattered brig, but she no longer wallowed on her side.

At last the stormy daylight broke. The mariners had survived, and they looked to find their two passengers, who had no other refuge than the cabin. Mr. Hunt was gone, blotted out with his affairs and his ambitions, whatever they were. The colored child they had vainly tried to find in the night. When the sea boiled into the cabin and filled it, she had climbed to the skylight in the roof, and there she clung like a bat. They hauled her out through a splintered gap, and sought tenderly to shelter her in a corner of the streaming deck, but she lived no more than a few hours. It was better that this bit of human flotsam should flutter out in this way than to linger a little longer in this forlorn derelict of a ship. The Polly could not sink, but she drifted as a mere bundle of boards with the ocean winds and currents, while seven men tenaciously fought off death and prayed for rescue.

The gale blew itself out, the sea rolled blue and gentle, and the wreck moved out into the Atlantic, having veered beyond the eastern edge of the Gulf Stream. There was raw salt pork and beef to eat, nothing else, barrels of which they fished out of the cargo. A keg of water which had been lashed to the quarter-deck was found to contain thirty gallons. This was all there was to drink, for the other water-casks had been smashed or carried away. The diet of meat pickled in brine aggravated the thirst of these castaways. For twelve days they chewed on this salty raw stuff, and then the Indian cook, Moho by name, actually succeeded in kindling a fire by rubbing two sticks together in some abstruse manner handed down by his ancestors. By splitting pine spars and a bit of oaken rail he was able to find in the heart of them wood which had not been dampened by the sea, and he sweated and grunted until the great deed was done. It was a trick which he was not at all sure of repeating unless the conditions were singularly favorable. Fortunately for the hapless crew of the Polly, their Puritan grandsires had failed in their amiable endeavor to exterminate the aborigine.

The tiny galley, or "camboose," as they called it, was lashed to ring-bolts in the deck, and had not been washed into the sea when the brig was swept clean. So now they patched it up and got a blaze going in the brick oven. The meat could be boiled, and they ate it without stint, assuming that a hundred barrels of it remained in the hold. It had not been discovered that the stern-post of the vessel was staved in under water and all of the cargo excepting some of the lumber had floated out.

The cask of water was made to last eighteen days by serving out a quart a day to each man. Then an occasional rain-squall saved them for a little longer from perishing of thirst. At the end of forty days they had come to the last morsel of salt meat. The Polly was following an aimless course to the eastward, drifting slowly under the influence of the ocean winds and currents. These gave her also a southerly slant, so that she was caught by that vast movement of water which is known as the Gulf Stream Drift. It sets over toward the coast of Africa and sweeps into the Gulf of Guinea.

The derelict was moving away from the routes of trade to Europe into the almost trackless spaces beneath the tropic sun, where the sea glittered empty to the horizon. There was a remote chance that she might be descried by a low-hulled slaver crowding for the West Indies under a mighty press of sail, with her human freightage jammed between decks to endure the unspeakable horrors of the Middle Passage. Although the oceans were populous with ships a hundred years ago, trade flowed on habitual routes. Moreover, a wreck might pass unseen two or three miles away. From the quarter-deck of a small sailing ship there was no such circle of vision as extends from the bridge of a steamer forty or sixty feet above the water, where the officers gaze through high-powered binoculars.

The crew of the Polly stared at skies which yielded not the merciful gift of rain. They had strength to build them a sort of shelter of lumber, but whenever the weather was rough, they were drenched by the waves which played over the wreck. At the end of fifty days of this hardship and torment the seven were still alive, but then the mate, Mr. Paddock, languished and died. It surprised his companions, for, as the old record rims,

he was a man of robust constitution who had spent his life in fishing on the Grand Banks, was accustomed to endure privations, and appeared the most capable of standing the shocks of misfortune of any of the crew. In the meridian of life, being about thirty-five years old, it was reasonable to suppose that, instead of the first, he would have been the last to fall a sacrifice to hunger and thirst and exposure, but Heaven ordered it otherwise.

Singularly enough, the next to go was a young seaman, spare and active, who was also a fisherman by trade. His name was Howe. He survived six days longer than the mate, and "likewise died delirious and in dreadful distress." Fleeting thunder-showers had come to save the others, and they had caught a large shark by means of a running bowline slipped over his tail while he nosed about the weedy hull. This they cut up and doled out for many days. It was certain, however, that unless they could obtain water to drink they would soon be all dead men on the Polly.

Captain Cazneau seems to have been a sailor of extraordinary resource and resolution. His was the unbreakable will to live and to endure which kept the vital spark flickering in his shipmates. Whenever there was strength enough among them, they groped in the water in the hold and cabin in the desperate hope of finding something to serve their needs. In this manner they salvaged an iron tea-kettle and one of the captain's flint-lock pistols. Instead of flinging them away, he sat down to cogitate, a gaunt, famished wraith of a man who had kept his wits and knew what to do with them.

At length he took an iron pot from the galley, turned the tea-kettle upside down on it, and found that the rims failed to fit together. Undismayed, the skipper whittled a wooden collar with a seaman's sheath-knife, and so joined the pot and the kettle. With strips of cloth and pitch scraped from the deck-beams, he was able to make a tight union where his round wooden frame set into the flaring rim of the pot. Then he knocked off the stock of the pistol and had the long barrel to use for a tube. This he rammed into the nozzle of the tea-kettle, and calked them as well as he could. The result was a crude apparatus for distilling sea-water, when placed upon the bricked oven of the galley.

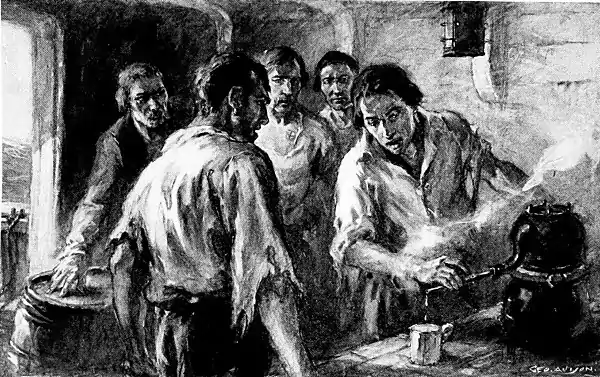

Imagine those three surviving seamen and the stolid redskin of a cook watching the skipper while he methodically tinkered and puttered! It was absolutely the one and final chance of salvation. Their lips were black and cracked and swollen, their tongues lolled, and they could no more than wheeze when they tried to talk. There was now a less precarious way of making fire than by rubbing dry sticks together. This had failed them most of the time. The captain had saved the flint and steel from the stock of his pistol. There was tow or tarry oakum to be shredded fine and used for tinder. This smoldered and then burst into a tiny blaze when the sparks flew from the flint, and they knew that they would not lack the blessed boon of fire.

Together they lifted the precious contrivance of the pot and the kettle and tottered with it to the galley. There was an abundance of fuel from the lumber, which was hauled through a hatch and dried on deck. Soon the steam was gushing from the pistol-barrel, and they poured cool salt water over the up-turned spout of the tea-kettle to cause condensation. Fresh water trickled from the end of the pistol-barrel, and they caught it in a tin cup. It was scarcely more than a drop at a time, but they stoked the oven and lugged buckets of salt water, watch and watch, by night and day. They roused in their sleep to go on with the task with a sort of dumb instinct. They were like wretched automatons.

So scanty was the allowance of water obtained that each man was limited to "four small wine glasses" a day, perhaps a pint. It was enough to permit them to live and suffer and hope. In the warm seas which now cradled the Polly the barnacles grew fast. The captain, the cook, and the three seamen scraped them off and for some time had no other food. They ate these shell-fish mostly raw, because cooking interfered with that tiny trickle of condensed water.

The faithful cook was the next of the five to succumb. He expired in March, after they had been three months adrift, and the manner of his death

FRESH WATER TRICKLED FROM THE END OF THE PISTOL-BARREL, AND THEY CAUGHT IT IN A TIN CUP

On the 15th of March, according to their computation, poor Moho gave up the ghost, evidently from want of water, though with much less distress than the others, and in the full exercise of his reason. He very devoutly prayed and appeared perfectly resigned to the will of God who had so sorely afflicted him.

The story of the Polly is unstained by any horrid episode of cannibalism, which occurs now and then in the old chronicles of shipwreck. In more than one seaport the people used to point at some weather-beaten mariner who was reputed to have eaten the flesh of a comrade. It made a marked man of him, he was shunned, and the unholy notoriety followed him to other ships and ports. The sailors of the Polly did cut off a leg of the poor, departed Moho, and used it as bait for sharks, and they actually caught a huge shark by so doing.

It was soon after this that they found the other pistol of the pair, and employed the barrel to increase the capacity of the still. By lengthening the tube attached to the spout of the tea-kettle, they gained more cooling surface for condensation, and the flow of fresh water now amounted to "eight junk bottles full" every twenty-four hours. Besides this, wooden gutters were hung at the eaves of the galley and of the rough shed in which they lived, and whenever rain fell, it ran into empty casks.

The crew was dwindling fast. In April, another seaman, Johnson by name, slipped his moorings and passed on to the haven of Fiddler's Green, where the souls of all dead mariners may sip their grog and spin their yarns and rest from the weariness of the sea. Three men were left aboard the Polly, the captain and two sailors.

The brig drifted into that fabled area of the Atlantic that is known as the Sargasso Sea, which extends between latitudes 16° and 38° North, between the Azores and the Antilles. Here the ocean currents are confused and seem to move in circles, with a great expanse of stagnant ocean, where the seaweed floats in tangled patches of red and brown and green. It was an old legend that ships once caught in the Sargasso Sea were unable to extricate themselves, and so rotted miserably and were never heard of again. Columbus knew better, for his caravels sailed through these broken carpets of weed, where the winds were so small and fitful that the Genoese sailors despaired of reaching anywhere. The myth persisted and it was not dispelled until the age of steam. The doldrums of the Sargasso Sea were the dread of sailing ships.

The days and weeks of blazing calms in this strange wilderness of ocean mattered not to the blindly errant wreck of the Polly. She was a dead ship that had outwitted her destiny. She had no masts and sails to push her through these acres of leathery kelp and bright masses of weed which had drifted from the Gulf and the Caribbean to come to rest in this solitary, watery waste. And yet to the captain and his two seamen this dreaded Sargasso Sea was beneficent. The stagnant weed swarmed with fish and gaudy crabs and mollusks. Here was food to be had for the mere harvesting of it. They hauled masses of weed over the broken bulwarks and picked off the crabs by hundreds. Fishing gear was an easy problem for these handy sailormen. They had found nails enough; hand-forged and malleable. In the galley they heated and hammered them to make fish-hooks, and the lines were of small stuff "unrove" from a length of halyard. And so they caught fish, and cooked them when the oven could be spared. Otherwise they ate them raw, which was not distasteful after they had become accustomed to it. The natives of the Hawaiian Islands prefer their fish that way. Besides this, they split a large number of small fish and dried them in the hot sun upon the roof of their shelter. The sea-salt which collected in the bottom of the still was rubbed into the fish. It was a bitter condiment, but it helped to preserve them against spoiling.

The season of spring advanced until the derelict Polly had been four months afloat and wandering, and the end of the voyage was a long way off. The minds and bodies of the castaways had adjusted themselves to the intolerable situation. The most amazing aspect of the experience is that these men remained sane. They must have maintained a certain order and routine of distilling water, of catching fish, of keeping track of the indistinguishable procession of the days and weeks. Captain Cazneau's recollection was quite clear when he came to write down his account of what had happened. The one notable omission is the death of another sailor, name unknown, which must have occurred after April. The only seaman who survived to keep the skipper company was Samuel Badger.

By way of making the best of it, these two indomitable seafarers continued to work on their rough deck-house, "which by constant improvement had become much more commodious." A few bundles of hewn shingles were discovered in the hold, and a keg of nails was found lodged in a corner of the forecastle. The shelter was finally made tight and weather-proof, but, alas! there was

"VOLUSIA" OFF SALEM, BUILT AT PLYMOUTH MASS., 1801, AND WRECKED AT CAPE COD IN 1908

From a painting in Marine Room, Peabody, Museum, Salem

The brig was drifting toward an ocean more frequented, where the Yankee ships bound out to the River Plate sailed in a long slant far over to the African coast to take advantage of the booming trade-winds. She was also wallowing in the direction of the route of the East Indiamen, which departed from English ports to make the far-distant voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. None of them sighted the speck of a derelict, which floated almost level with the sea and had no spars to make her visible. Captain Cazneau and his companion saw sails glimmer against the sky-line during the last thousand miles of drift, but they vanished like bits of cloud, and none passed near enough to bring salvation.

June found the Polly approaching the Canary Islands. The distance of her journey had been about two thousand miles, which would make the average rate of drift something more than three hundred miles a month, or ten miles per day. The season of spring and its apple blossoms had come and gone in New England, and the brig had long since been mourned as missing with all hands. It was on the twentieth of June that the skipper and his companion—two hairy, ragged apparitions—saw three ships which appeared to be heading in their direction. This was in latitude 28° North and longitude 13° West, and if you will look at a chart you will note that the wreck would soon have stranded on the coast of Africa. The three ships, in company, bore straight down at the pitiful little brig, which trailed fathoms of sea-growth along her hull. She must have seemed uncanny to those who beheld her and wondered at the living figures that moved upon the weather-scarred deck. She might have inspired "The Ancient Mariner."

Not one ship, but three, came bowling down to hail the derelict. They manned the braces and swung the main-yards aback, beautiful, tall ships and smartly handled, and presently they lay hove to. The captain of the nearest one shouted a hail through his brass trumpet, but the skipper of the Polly had no voice to answer back. He sat weeping upon the coaming of a hatch. Although not given to emotion, he would have told you that it had been a hard voyage. A boat was dropped from the davits of this nearest ship, which flew the red ensign from her spanker-gaff. A few minutes later Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger, able seaman, were alongside the good ship Fame of Hull, Captain Featherstone, and lusty arms pulled them up the ladder. It was six months to a day since the Polly had been thrown on her beam-ends and dismasted.

The three ships had been near together in light winds for several days, it seemed, and it occurred to their captains to dine together on board the Fame. And so the three skippers were there to give the survivors of the Polly a welcome and to marvel at the yarn they spun. The Fame was homeward bound from Rio Janeiro. It is pleasant to learn that Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger "were received by these humane Englishmen with expressions of the most exalted sensibility." The musty old narrative concludes:

Here the curtain falls. I for one should like to hear more incidents of this astonishing cruise of the derelict Polly and also to know what happened to Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger after they reached the port of Boston. Probably they went to sea again, and more than likely in a privateer to harry British merchantmen, for the recruiting officer was beating them up to the rendezvous with fife and drum, and in August of 1812 the frigate Constitution, with ruddy Captain Isaac Hull walking the poop in a gold-laced coat, was pounding the Guerrière to pieces in thirty minutes, with broadsides whose thunder echoed round the world.

"Ships are all right. It is the men in them," said one of Joseph Conrad's wise old mariners. This was supremely true of the little brig that endured and suffered so much, and among the humble heroes of blue water by no means the least worthy to be remembered are Captain Cazneau and Samuel Badger, able seaman, and Moho, the Indian cook.