Lincoln's Last Day

NEW FACTS NOW TOLD FOR THE FIRST TIME

BY WILLIAM H. CROOK (HIS PERSONAL BODY GUARD)

COMPILED AND WRITTEN DOWN BY MARGARITA SPALDING GERRY

AS March 31, 1865, drew near, the President (then at City Point, Virginia) knew that Grant was to make a general attack upon Petersburg, and grew depressed. The fact that his own son was with Grant was one source of anxiety. But the knowledge of the loss of life that must follow hung about him until he could think of nothing else. On the 31st there was, of course, no news. Most of the first day of April Mr. Lincoln spent in the telegraph-office, receiving telegrams and sending them on to Washington. Toward evening he came hack to the River Queen, on which we had sailed from Washington to City Point.

There his anxiety became more intense. There had been a slight reverse during the day; he feared that the struggle might be prolonged. We could hear the cannon as they pounded away at Drury's Bluff up the river. We knew that not many miles away Grant was pouring fire into Lee's forces about Petersburg.

It grew dark. Then we could see the flash of the cannon. Mr. Lincoln would not go to his room. Almost all night he walked up and down the deck, pausing now and then to listen or to look out into the darkness to see if he could see anything. I have never seen such suffering in the face of any man as was in his that night.

On the morning of April 2d a message came from General Grant asking the President to come to his headquarters, some miles distant from City Point and near Petersburg. It was on Sunday. We rode out to the entrenchments, close to the battle-ground. Mr. Lincoln watched the life-and-death struggle for some time, and then returned to City Point. In the evening he received a despatch from General Grant telling him that he had pushed Lee to his last lines about Petersburg. The news made the President happy. He said to Captain Penrose that the end of the war was now in sight. He could go to bed and sleep now. I remember how cheerful was his "Good night, Crook."

On Monday, the 3d, a message came to the President that Petersburg was in possession of the Federal army, and that General Grant was waiting there to see him. We mounted and rode over the battle-field to Petersburg. As we rode through Fort Hell and Fort Damnation—as the men had named the outposts of the two armies which faced each other, not far apart—many of the dead and dying were still on the ground. I can still see one man with a bullet-hole through his forehead and another with both arms shot away. As we rode, the President's face settled into its old lines of sadness.

At the end of fifteen miles we reached Petersburg, and were met by Captain Robert Lincoln of General Grant's staff, who, with some other officers, escorted us to General Grant. We found him and the rest of his staff sitting on the piazza of a white frame house. Grant did not look like one's idea of a conquering hero. He didn't appear exultant, and he was as quiet as he had ever been. The meeting between Grant and Lincoln was cordial; the President was almost affectionate. While they were talking I took the opportunity to stroll through Petersburg. It seemed deserted, but I met a few of the inhabitants. They said they were glad that the Union army had taken possession; they were half starved. They certainly looked so. The tobacco warehouses were on fire, and boys were carrying away tobacco to sell to the soldiers. I bought a five-pound bale of smoking-tobacco for twenty-five cents. Just before we started back a little girl came up with a bunch of wild flowers for the President. He thanked the child for them kindly, and we rode away. Soon after we got back to City Point news came of the evacuation of Richmond.

In the midst of the rejoicing some Confederate prisoners were brought aboard transports at the dock near us. The President hung over the rail and watched them. They were in a pitiable condition, ragged and thin; they looked half starved. When they were on board they took out of their knapsacks the last rations that had been issued to them before capture. There was nothing but bread, which looked as if it had been mixed with tar. When they cut it we could see how hard it was and heavy; it was more like cheese than bread.

"Poor fellows!" Mr. Lincoln said. "It's a hard lot. Poor fellows—"

I looked up. His face was pitying and sorrowful. All the happiness had gone.

On the 4th of April, Admiral Porter asked the President to go to Richmond with him. At first the President did not want to go. He knew it was foolhardy. And he had no wish to see the spectacle of the Confederacy's humiliation. It has been generally believed that it was Mr. Lincoln's own idea, and he has been blamed for rashness because of it. I understand that when Mr. Stanton, who was a vehement man, heard that the expedition had started, he was so alarmed that he was angry against the President. "That fool!" he exclaimed. Mr. Lincoln knew perfectly well how dangerous the trip was, and, as I said, at first he did not want to go, realizing that he had no right to risk his life unnecessarily. But he was convinced by Admiral Porter's arguments. Admiral Porter thought that the President ought to be in Richmond as soon after the surrender as possible. In that way he could gather up the reins of government most readily and give an impression of confidence in the South that would be helpful in the reorganization of the government. Mr. Lincoln immediately saw the wisdom of this position and went forward, calmly accepting the possibility of death.

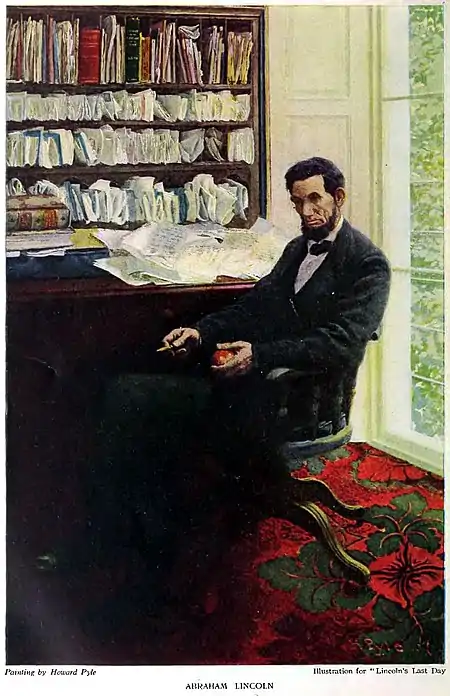

Mrs. Lincoln, by this time, had gone back to Washington. Mr. Lincoln, Taddie and I went up the James River on the River Queen to meet Admiral Porter's fleet. Taddie went down immediately to inspect the engine and talk with his friends the sailors; the President remained on deck. Near where Mr. Lincoln sat was a large bowl of apples on a table; there must have been at least half a peck. The President reached forward for one.

"These must have been put here for us," he said. "I guess I will sample them." We both began to pare and eat. Before we reached the Admiral's flag-ship every apple had disappeared—and the parings too. When the last one was gone the President said with a smile, "I guess I have cleaned that fellow out."

When we had met Admiral Porter's fleet the question of the best way to get to Richmond had to be decided. While some effort had been made to fish the torpedoes and other obstructions out of the water, but little headway had been made. The river was full of wreckage of all sorts, and torpedoes were floating everywhere. The plan had been to sail to Richmond in Admiral Porter's flag-ship Malvern, escorted by the Bat, and with the Columbus for the horses. But it was soon evident that it would not be possible to get so large a boat through at Drury's Bluff, where the naturally narrow and rapid channel was made impassable by a boat which had missed the channel and gone aground. It was determined to abandon the Malvern for the captain's gig, manned by twelve sailors. When the party, consisting of President Lincoln, Admiral Porter, Captain Penrose, Taddie and myself, were seated, a little tug, the Bat, which the President had used for his trips about City Point, came alongside and took us in tow. There were a number of marines on board the tug. We were kept at a safe distance from the tug by means of a long hawser, so that if she struck a torpedo and was blown up, the President and his party would be safe. Even with this precaution the trip was exciting enough. On either side dead horses, broken ordnance, wrecked boats, floated near our boat, and we passed so close to torpedoes that we could have put out our hands and touched them. We were dragged over one wreck which was so near the surface that it could be clearly seen.

Beyond Drury's Bluff, at a point where a bridge spans the water, the tug was sent back to help a steamboat which had stuck fast across the stream. It seems that it was the Allison, a captured Confederate vessel, and Admiral Farragut, who had taken it, was on board. The marines, of course, went with the tug. In the attempt to help the larger boat the tug was grounded. Then we went on with no other motive-power than the oars in the arms of the twelve sailors.

The shore for some distance before we reached Richmond was black with negroes. They had heard that President Lincoln was on his way—they had some sort of an underground telegraph, I am sure. They were wild with excitement and yelling like so many wild men: "Dar comes Massa Linkum, de Sabier ob de lan'—we is so glad to see him!" We landed at the Rocketts, over a hundred yards back of Libbey Prison. By the time we were on shore hundreds of black hands were outstretched to the President, and he shook some of them and thanked the darkies for their welcome. While we stood still a few minutes before beginning our walk through the city, we saw some soldiers not far away "initiating" some negroes by tossing them on a blanket. When they came down they were supposed to be transformed into Yankees. The darkies yelled lustily during the process, and came down livid under their black skins." But they were all eager for the ordeal. The President laughed boyishly—I heard him afterward telling some one about the funny sight.

We formed in line. Six sailors were in advance and six in the rear. They were armed with short carbines. Mr. Lincoln was in the centre, with Admiral Porter and Captain Penrose on the right and I on the left, holding Taddie by the hand. I was armed with a Colt's revolver. We looked more like prisoners than anything else as we walked up the streets of Richmond not thirty-six hours after the Confederates had evacuated.

At first, except the blacks, there were not many people on the streets. But soon we were walking through streets that were alive with spectators. Wherever it was possible for a human being to find a foothold there was some man or woman or boy straining his eyes after the President. Every window was crowded with heads. Men were hanging from tree-boxes and telegraph-poles. But it was a silent crowd. There was something oppressive in those thousands of watchers without a sound, either of welcome or hatred. I think we would have welcomed a yell of defiance. I stole a look sideways at Mr. Lincoln. His face was set. It had the calm in it that comes over the face of a brave man when he is ready for whatever may come. In all Richmond the only sign of welcome I saw, after we left the negroes at the landing-place and until we reached our own men, was from a young lady who was on a sort of bridge that connected the Spottswood House with another hotel across the street. She had an American flag over her shoulders.

We had not gone far when the blinds of a second-story window of a house on our left were partly opened, and a man dressed in gray pointed something that looked like a gun directly at the President. I dropped Tad's hand and stepped in front of Mr. Lincoln. Later the President explained it otherwise. But we were all so aware of the danger of his entrance into Richmond right on the heels of the army, with such bitterness of feeling on the part of the Confederates, the streets swarming with disorderly characters, that our nerves were not steady. It seems to me nothing short of miraculous that some attempt on his life was not made. It is to the everlasting glory of the South that he was permitted to come and go in peace.

We were glad when we reached General Weitzel's headquarters in the abandoned Davis mansion and were at last among friends. Every one relaxed in the generous welcome of the General and his staff. The President congratulated General Weitzel and a jubilation followed.

The Jefferson Davis home was a large house of gray stucco, with a garden at the back. It was a fine place, though everything looked dilapidated after the long siege. It was still completely furnished, and there was an old negro house-servant in charge. He told me that Mrs. Davis had ordered him to have the house in good condition for the Yankees.

"I am going out into the world a wanderer without a home," she had said when she bade him good-by.

I was glad to know that he was to have everything "in good condition," for I was thirsty after so much excitement, and surely his orders must have included something to drink. I put the question to him. He said,

"Yes, indeed, boss, there is some fine old whiskey in the cellar."

In a few minutes he produced a long, black bottle. The bottle was passed around. When it came back it was empty. Every one had taken a pull except the President, who never touched anything of the sort.

An officer's ambulance was brought to the door, and President Lincoln, Admiral Porter, General Weitzel with some of his staff. Captain Penrose, and Taddie took their seats. There was no room for me.

"Where is the place for Crook?" Mr. Lincoln asked. "I want him to go with me." Then they provided me with a saddle-horse, and I rode by the side on which Mr. Lincoln sat. We went through the city. Everywhere were signs of war, hundreds of homes had been fired, in some places buildings were still burning. It was with difficulty that we could get along, the crowd was so great. We passed Libbey Prison. The only place that we entered was the Capitol. We were shown the room that had been occupied by Davis and his cabinet. The furniture was completely wrecked; the coverings of desks and chairs had been stripped off by relic-hunters, and the chairs were hacked to pieces.

The ambulance took us back to the wharf. Admiral Porter's flag-ship Malvern had by this time made her way up the river, and we boarded her. It was with a decided feeling of relief that we saw the President safe on board.

We did not start back until the next morning, so there was time for several rumors of designs against the President's life to get abroad. But although he saw many visitors, there was no attempt against him. Nothing worse happened than the interview with Mr. Duff Green.

Duff Green was a conspicuous figure at the time. He was a newspaper man, an ardent rebel. He always carried with him a huge staff, as tall as he was himself—and he was a tall man. Admiral Porter published an account of the interview in the New York Tribune of January, 1885, which was not altogether accurate. What really happened was this:

As Mr. Green approached him, the President held out his hand. Mr. Green refused to take it, saying, "I did not come to shake hands." Mr. Lincoln then sat down; so did Mr. Green. There were present at the time General Weitzel, Admiral Porter, one or two others, and myself. Mr. Green began to abuse Mr. Lincoln for the part he had taken in the struggle between the North and the South. His last words were:

"I do not know how God and your conscience will let you sleep at night after being guilty of the notorious crime of setting the niggers free."

The President listened to his diatribe without the slightest show of emotion. He said nothing. There was nothing in his face to show that he was angry. When Mr. Green had exhausted himself, he said,

"I would like, sir, to go to my friends."

The President turned to General Weitzel and said, "General, please give Mr. Green a pass to go to his friends." Mr. Green was set ashore and was seen no more.

That night Taddie and I were fast asleep, when I was startled into wakefulness. Something tall and white and ghostly stood by my berth. For a moment I trembled. When I was fairly awake I saw that it was Mr. Lincoln in his long white nightgown. He had come in to see if Taddie was all right. He stopped to talk a few minutes.

He referred to Mr. Duff Green: "The old man is pretty angry, but I guess he will get over it." Then he said, "Good night and a good night's rest, Crook," and he went back to his stateroom.

Our return trip to City Point was in the Malvern, and quiet enough in comparison with the approach to Richmond. When we reached the "Dutch Gap Canal," which was one of the engineering features of the day, the President wanted to go through it. Admiral Porter lowered a boat, and in it we passed through the canal to the James below. The canal cuts off a long loop of the river. We had to wait some time for the Malvern to go round.

Mrs. Lincoln had returned to City Point with a party which included Senator Sumner and Senator and Mrs. Harlan. They made a visit to Richmond, accompanied by Captain Penrose, while the President remained at City Point, the guest of Admiral Porter, until the 8th. Then, having heard of the injury to Secretary Seward when he was thrown from his carriage in a runaway accident, he felt that he must go back to Washington. He had intended to remain until Lee surrendered.

We reached home Sunday evening, the 9th. The President's carriage met us at the wharf. There Mr. Lincoln parted from Captain Penrose; he took the captain by the hand and thanked him for the manner in which he had performed his duty. Then he started for the White House.

The streets were alive with people, all very much excited. There were bonfires everywhere. We were all curious to know what had happened. Tad was so excited he couldn't keep still. We halted the carriage and asked a bystander,

"What has happened?"

He looked at us in amazement, not recognizing Mr. Lincoln:

"Why, where have you been? Lee has surrendered."

There is one point which is not understood, I think, about the President's trip to City Point and Richmond. I would like to tell here what my experience has made me believe. The expedition has been spoken of almost as if it were a pleasure trip. Some one says of it, "It was the first recreation the President had known." Of course in one sense this was true. He did get away from the routine of office work. He had pleasant associations with General Grant and General Sherman and enjoyed genial talks in the open over the camp-fire. But to give the impression that it was a sort of holiday excursion is a mistake. It was a matter of executive duty, and a very trying and saddening duty in many of its features. The President's suspense during the days when he knew the battle of Petersburg was imminent, his agony when the thunder of the cannon told him that men were being cut down like grass, his sight of the poor torn bodies of the dead and dying on the field of Petersburg, his painful sympathy with the forlorn rebel prisoners, the revelation of the devastation of a noble people in ruined Richmond—these things may have been compensated for by his exultation when he first knew the long struggle was over. But I think not. These things wore new furrows in his face. Mr. Lincoln never looked sadder in his life than when he walked through the streets of Richmond and knew it saved to the Union, and himself victorious.

Although I reported early at the White House on the morning after our return from City Point, I found the President already at his desk. He was looking over his mail, but as I came in he looked up and said pleasantly:

"Good morning. Crook. How do you feel?"

I answered: "First rate, Mr. President. How are you?"

"I am well, but rather tired," he said.

Then I noticed that he did look tired. His worn face made me understand, more clearly than I had done before, what a strain the experiences at Petersburg and Richmond had been. Now that the excitement was over, the reaction allowed it to be seen.

I was on duty near the President all that day. We settled back into the usual routine. It seemed odd to go on as if nothing had happened; the trip had been such a great event. It was a particularly busy day. Correspondence had been held for Mr. Lincoln's attention during the seventeen days of absence; besides that, his office was thronged with visitors. Some of them had come to congratulate him on the successful outcome of the war; others had come to advise him what course to pursue toward the conquered Confederacy; still others wanted appointments. One gentleman, who was bold enough to ask aloud what everybody was asking privately, said,

"Mr. President, what will you do with Jeff Davis when he is caught?"

Mr. Lincoln sat up straight and crossed his legs, as he always did when he was going to tell a story.

"Gentlemen," he said, "that reminds me"—at the familiar words every one settled back and waited for the story—"that reminds me of an incident which occurred in a little town in Illinois where I once practised law. One morning I was on my way to the office, when I saw a boy standing on the street corner crying. I felt sorry for the woebegone little fellow. So I stopped and questioned him as to the cause of his griefs. He looked into my face, the tears running down his cheeks, and said, 'Mister, do you see that coon?—pointing to a very poor specimen of the coon family which glared at us from the end of the string. 'Well, sir, that coon has given me a heap of trouble. He has nearly gnawed the string in two—I just wish he would finish it. Then I could go home and say he had got away.' "

Everybody laughed. They all knew quite well what the President would like to do with Jeff Davis—when Jeff Davis was caught.

Later in the morning a great crowd came marching into the White House grounds. Every man was cheering and a band was playing patriotic airs. The workmen at the Navy-Yard had started the procession, and by the time it had reached us it was over two thousand strong. Of course they called for the President, and he stepped to the window to see his guests. When the cheering had subsided he spoke to them very kindly and good-naturedly, begging that they would not ask him for a serious speech.

"I am going to make a formal address this evening," he said, "and if I dribble it out to you now, my speech to-night will be spoiled." Then, with his humorous smile, he spoke to the band:

"I think it would be a good plan for you to play 'Dixie.' I always thought that it was the most beautiful of our songs. I have submitted the question of its ownership to the Attorney-General, and he has given it as his legal opinion that we have fairly earned the right to have it back." As the opening bars of "Dixie" burst out, Mr. Lincoln disappeared from the window. The crowd went off in high good humor, marching to the infectious rhythm of the hard-won tune.

On the afternoon of the same day, about six o'clock, a deputation of fifteen men called. Mr. Lincoln met them in the corridor just after they had entered the main door. They were presented to the President, and then the gentleman who had introduced them made a speech. It was a very pretty speech, full of loyal sentiments and praise for the man who had safely guided the country through the great crisis. Mr. Lincoln listened to them pleasantly. Then a picture was put into his hands. When he saw his own rugged features facing him from an elaborate silver frame a smile broadened his face.

"Gentlemen," he said, "I thank you for this token of your esteem. You did your best. It wasn't your fault that the frame is so much more rare than the picture."

On the evening of the 11th the President made the speech which he had promised the day before. Had we only known it, this was to be his last public utterance. The whole city was brilliantly illuminated that night. The public buildings were decorated and, from the Capitol to the Treasury, the whole length of Pennsylvania Avenue bore witness, with flags and lights, to the joy everybody felt because the war was over. Streaming up Pennsylvania Avenue, which was the one great thoroughfare then, the only paved street, and from every other quarter of the city, came the people. In spite of the unpleasant drizzle which fell the whole evening and the mud through which every one had to wade, a great crowd cheered Mr. Lincoln when he appeared at an upper window. From another window Mrs. Lincoln bowed to the people and was greeted enthusiastically. The President immediately began his speech, which had been in preparation ever since his return from City Point. The care which he had taken to express himself accurately was shown from the fact that the whole address was written out. Inside, little Tad was running around the room while "papa-day" was speaking. As the President let the sheets of manuscript fall, Taddie gathered them up and begged his father to let them go faster.

The President spoke with reverence of the cause for thanksgiving that the long struggle was over. He passed rapidly to that question which he knew the whole nation was debating—the future policy toward the South. In discussing his already much-debated "Louisiana Policy" he expressed the two great principles which were embodied in it: the mass of the Southern people should be restored to their citizenship as soon as it was evident that they desired it; punishment, if punishment there be, should fall upon those who had been proved to be chiefly instrumental in leading the South into rebellion. These principles were reiterated by Senator Harlan, the Secretary of the Interior to be, who spoke after the President; they were reiterated, of course, by the President's desire. During President Andrew Johnson's long struggle with a bitter Northern Congress, I have often recalled the simplicity and kindliness of Abraham Lincoln's theory.

During the next three days—as, in fact, since the fall of Richmond—Washington was a little delirious. Everybody was celebrating. The kind of celebration depended on the kind of person. It was merely a question of whether the intoxication was mental or physical. Every day there was a stream of callers who came to congratulate the President, to tell how loyal they had been, and how they had always been sure he would be victorious. There were serenades; there were deputations of leading citizens; on the evening of the 13th there was another illumination. The city became disorderly with the men who were celebrating too hilariously. Those about the President lost somewhat of the feeling, usually present, that his life was not safe. It did not seem possible that, now that the war was over and the government—glad to follow General Grant's splendid initiative—had been so magnanimous in its treatment of General Lee, after President Lincoln had offered himself a target for Southern bullets in the streets of Richmond and had come out unscathed, there could be danger. For my part, I had drawn a full breath of relief after we got out of Richmond and had forgotten to be anxious since.

Because of the general joyousness, I was surprised when, late on the afternoon of the 14th, I accompanied Mr. Lincoln on a hurried visit to the War Department, I found that the President was more depressed than I had ever seen him and his step unusually slow. Afterward Mrs. Lincoln told me that when he drove with her to the Soldiers' Home earlier in the afternoon he had been extremely cheerful, even buoyant. She said that he had talked of the calm future that was in store for them, of the ease which they had never known, when, his term over, they would go back to their home in Illinois. He longed, a little wistfully, for that time to come with its promise of peace. The depression I noticed may have been due to one of the sudden changes of mood to which I have been told the President was subject. I had heard of the transitions from almost wild spirits to abject melancholy which marked him. I had never seen anything of the sort, and had concluded that all this must have belonged to his earlier days. In the time when I knew him his mood, when there was no outside sorrow to disturb him, was one of settled calm. I wondered at him that day and felt uneasy.

In crossing over to the War Department we passed some drunken men. Possibly their violence suggested the thought to the President. After we had passed them, Mr. Lincoln said to me:

"Crook, do you know, I believe there are men who want to take my life?" Then, after a pause, he said, half to himself, "And I have no doubt they will do it."

The conviction with which he spoke dismayed me. I wanted to protest, but his tone had been so calm and sure that I found myself saying instead, "Why do you think so, Mr. President?"

"Other men have been assassinated," was his reply, still in that manner of stating something to himself.

All I could say was, "I hope you are mistaken, Mr. President."

We walked a few paces in silence. Then he said, in a more ordinary tone:

"I have perfect confidence in those who are around me, in every one of you men. I know no one could do it and escape alive. But if it is to be done, it is impossible to prevent it."

By this time we were at the War Department, and he went in to his conference with Secretary Stanton. It was shorter than usual that evening. Mr. Lincoln was belated. When Mrs. Lincoln and he came home from their drive he had found friends awaiting him. He had slipped away from dinner, and there were more people waiting to talk to him when he got back. He came out of the Secretary's office in a short time. Then I saw that every trace of the depression, or perhaps I should say intense seriousness, which had surprised me before had vanished. He talked to me as usual. He said that Mrs. Lincoln and he, with a party, were going to the theatre to see Our American Cousin.

"It has been advertised that we will be there," he said, "and I cannot disappoint the people. Otherwise I would not go. I do not want to go."

I remember particularly that he said this, because it surprised me. The President's love for the theatre was well known. He went often when it was announced that he would be there; but more often he would slip away, alone or with Tad, get into the theatre, unobserved if he could, watch the play from the back of the house for a short time, and then go back to his work. Mr. Buckingham, the doorkeeper of Ford's Theatre, used to say that he went in just to "take a laugh." So it seemed unusual to hear him say he did not want to go. When we had reached the White House and he had climbed the steps he turned and stood there a moment before he went in. Then he said,

"Good-by, Crook."

It startled me. As far as I remember he had never said anything but "Good night, Crook," before. Of course it is possible that I may be mistaken. In looking back, every word that he said has significance. But I remember distinctly the shock of surprise and the impression, at the time, that he had never said it before.

By this time I felt queer and sad. I hated to leave him. But he had gone in, so I turned away and started on my walk home. I lived in a little house on "Rodbird's Hill." It was a long distance from the White House—it would be about on First Street now in the middle of the block between L and M streets. The whole tract from there to North Capitol Street belonged either to my father-in-law or to his family. He was an old retired sea-captain named Rodbird; he had the hull of his last sailing-vessel set up in his front yard.

The feeling of sadness with which I left the President lasted a long time, but after a while—I was young and healthy, I was going home to my wife and baby, and, the man who followed me on duty having been late for some reason, it was long past my usual dinner-time, and I was hungry. By the time I had had my dinner I was sleepy, so I went to bed early. I did not hear until early in the morning that the President had been shot. It seems incredible now, but it was so.

My first thought was—If I had been on duty at the theatre, I would be dead now. My next was to wonder whether Parker, who had gone to the theatre with the President, was dead. Then I remembered what the President had said the evening before. Then I went to the house on Tenth Street where they had taken him.

They would not let me in. The little room where he lay was crowded with the men who had been associated with the President during the war. They were gathered around the bed watching, while, long after the great spirit had flown, life, little by little, loosened its hold on the long, gaunt body. Among them, I knew, were men who had contended with him during his life or who had laughed. Charles Sumner stood at the very head of the bed. I know that it was to him that Robert Lincoln, who was only a boy for all his shoulder-straps, turned in the long strain of watching. And on Charles Sumner's shoulder the son sobbed out his grief. But the room was full, and they would not let me in.

After the President had died they took him back to the White House. It was to the guest-room with its old four-poster bed that they carried him. I was in the room while the men prepared his body to be seen by his people when they came to take their leave. It was hard for me to be there. It seemed fitting that the body should be there, where he had never been in life. I am glad that his own room could be left to the memory of his living presence.

The days during which the President lay in state before they took him away for his long progress over the country he had saved were even more distressing than grief would have made them. Mrs. Lincoln was almost frantic with suffering. Some women spiritualists in some way gained access to her. They poured into her ears pretended messages from her dead husband. Mrs. Lincoln was so weakened that she had not force enough to resist the cruel cheat. These women nearly crazed her. Mr. Robert Lincoln, who had to take his place now as the head of the family, finally ordered them out of the house.

After the President's remains were taken from the White House, the family began preparations for leaving, but they were delayed a month by Mrs. Lincoln's illness. The shock of her husband's death had brought about a nervous disorder. Her physician, Dr. Stone, refused to allow her to be moved until she was somewhat restored. During the whole of the time while she was shut up in her room Mrs. Gideon Welles, the wife of the Secretary of the Navy, was in almost daily attendance upon her. Mrs. Welles was Mrs. Lincoln's friend, of all the women in official position, and she did much with her kindly ministrations to restore the President's widow to her normal condition. It was not until the 23d of May, at six o'clock, that Mrs. Lincoln finally left for Chicago.

Captain Robert Lincoln accompanied her, and a colored woman, a seamstress, in whom she had great confidence, went with the party to act as Mrs. Lincoln's maid. They asked me to go with them to do what I could to help. But no one could do much for Mrs. Lincoln. During most of the fifty-four hours that we were on the way she was in a daze; it seemed almost a stupor. She hardly spoke. No one could get near enough to her grief to comfort her. But I could be of some use to Taddie. Being a child, he had been able to cry away some of his grief, and he could be distracted with the sights out of the car window. There was an observation-car at the end of our coach. Taddie and I spent a good deal of time there, looking at the scenes flying past. He began to ask questions.

It had been expected that Mrs. Lincoln would go back to her old home in Illinois. But she did not seem to be able to make up her mind to go there. She remained for some time in Chicago at the old Palmer House.

I went to a friend who had gone to Chicago to live from Washington and remained with him for the week I was in the city. I went to the hotel every day. Mrs. Lincoln I rarely saw. Taddie I took out for a walk almost every day and tried to interest him in the sights we saw. But he was a sad little fellow and mourned for his father.

At last I went back to Washington and to the White House. President Johnson had established his offices there when I got back.

Now that I have told the story of my three months' association with Abraham Lincoln, there are two things of which I feel that I must speak. The first question relates to the circumstances of the assassination of President Lincoln. It has never been made public before.

I have often wondered why the negligence of the guard who accompanied the President to the theatre on the night of the 14th has never been divulged. So far as I know, it was never even investigated by the police department. Yet, had he done his duty, I believe President Lincoln might not have been murdered by Booth. The man was John Parker. He was a native of the District, and had volunteered, as I believe each of the other guards had done, in response to the President's first call for troops from the District. He is dead now and, as far as I have been able to discover, all of his family. So it is no unkindness to speak of the costly mistake he made.

It was the custom for the guard who accompanied the President to the theatre to remain in the little passageway outside the box—that passageway through which Booth entered. Mr. Buckingham, who was the doorkeeper at Lord's Theatre, remembers that a chair was placed there for the guard on the evening of the 14th. Whether Parker occupied it at all I do not know—Mr. Buckingham is of the impression that he did. If he did, he left it almost immediately; for he confessed to me the next day that he went to a seat at the front of the first gallery so that he could see the play. The door of the President's box was shut; probably Mr. Lincoln never knew that the guard had left his post.

Mr. Buckingham tells that Booth was in and out of the house five times before he finally shot the President. Each time he looked about the theatre in a restless, excited manner. I think there can be no doubt that he was studying the scene of his intended crime, and that he observed that Parker, whom he must have been watching, was not at his post. To me it is very probable that the fact that there was no one on guard may have determined the time of his attack. Booth had found it necessary to stimulate himself with whiskey in order to reach the proper pitch of fanaticism. Had he found a man at the door of the President's box armed with a Colt's revolver, his alcohol courage might have evaporated.

However that may be, Parker's absence had much to do with the success of Booth's purpose. The assassin was armed with a dagger and a pistol. The story used to be that the dagger was intended for General Grant when the President had been despatched. That is absurd. While it had been announced that General and Mrs. Grant would be in the box, Booth, during one of his five visits of inspection, had certainly had an opportunity to observe that the General was absent. The dagger, which was noiseless, was intended for any one who might intercept him before he could fire. The pistol, which was noisy and would arouse pursuit, was for the President. As it happened, since the attack was a complete surprise, Major Rathbone, who, the President having been shot, attempted to prevent Booth's escape, received the dagger in his arm.

Had Parker been at his post at the back of the box—Booth still being determined to make the attempt that night—he would have been stabbed, probably killed. The noise of the struggle—Parker could surely have managed to make some outcry—would have given the alarm. Major Rathbone was a brave man, and the President was a brave man and of enormous muscular strength. It would have been an easy thing for the two men to have disarmed Booth, who was not a man of great physical strength. It was the suddenness of his attack on the President that made it so devilishly successful. It makes me feel rather bitter when I remember that the President had said, just a few hours before, that he knew he could trust all his guards. And then to think that in that one moment of test one of us should have utterly failed him! Parker knew that he had failed in duty. He looked like a convicted criminal the next day. He was never the same man afterward.

The other fact that I think people should know has been stated before in the President's own words: President Lincoln believed that it was probable he would be assassinated.

The conversation that I had with him on the 14th was not the only one we had on that same subject. Any one can see how natural it was that the matter should have come up between us—my very presence beside him was a reminder that there was danger of assassination. In his general kindliness he wanted to talk about the thing that constituted my own particular occupation. He often spoke of the possibility of an attempt being made on his life. With the exception of that last time, however, he never treated it very seriously. He merely expressed the general idea that, I afterwards learned, he had expressed to Marshal Lamon and other men: if any one was willing to give his own life in the attempt to murder the President, it would be impossible to prevent him.

On that last evening he went further. He said with conviction that he believed that the men who wanted to take his life would do it.. As far as I know, I am the only person to whom President Lincoln made such a statement. He may possibly have spoken about it to the other guards, but I never heard of it, and I am sure that had he done so I would have known of it.

More than this, I believe that he had some vague sort of a warning that the attempt would be made on the night of the 14th. I know that this is an extraordinary statement to make, and that it is late in the day to make it. I have been waiting for just the proper opportunity to say this thing; I did not care to talk idly about it. I would like to give my reasons for feeling as I do. The chain of circumstances is at least an interesting thing to consider.

It is a matter of record that on the morning of the 14th, at a cabinet meeting, the President spoke of the recurrence the night before of a dream which, he said, had always forerun something of moment in his life. In the dream a ship under full sail bore down upon him. At the time he spoke of it he felt that some good fortune was on its way to him. He was serene, even joyous, over it. Later in the day, while he was driving with his wife, his mind still seemed to be dwelling on the question of the future. It was their future together of which he spoke. He was almost impatient that his term should be over. He seemed eager for rest and peace. When I accompanied him to the War Department, he had become depressed and spoke of his belief that he would be assassinated. When we returned to the White House, he said that he did not want to go to the theatre that evening, but that he must go so as not to disappoint the people. In connection with this it is to be remembered that he was extremely fond of the theatre, and that the bill that evening, Our American Cousin, was a very popular one. When he was about to enter the White House he said "Good-by," as I never remember to have heard him say before when I was leaving for the night.

These things have a curious interest. President Lincoln was a man of entire sanity. But no one has ever sounded the spring of spiritual insight from which his nature was fed. To me it all means that he had, with his waking on that day, a strong prescience of coming change. As the day wore on, the feeling darkened into an impression of coming evil. The suggestion of the crude violence we witnessed on the street pointed to the direction from which that evil should come, he was human; he shrank from it. But he had what some men call fatalism; others, devotion to duty; still others, religious faith. Therefore he went open-eyed to the place where he met, at last, the blind fanatic. And in that meeting the President, who had dealt out justice with a tender heart, who had groaned in spirit over fallen Richmond, fell.

More and more, people who have heard that I was with Mr. Lincoln come to me asking,

"What was he like?"

These last years, when, at a Lincoln birthday celebration or some other memorial gathering, they ask for a few words from the man who used to be Abraham Lincoln's guard, the younger people look at me as if I were some strange spectacle—a man who lived by Lincoln's side. It has made me feel as if the time had come when I ought to tell the world the little that I know about him. Soon there will be nothing of him but the things that have been written.

Yet, when I try to say what sort of a man he seemed to me, I fail. I have no words. All I can do is to give little snatches of reminiscences—I cannot picture the man. I can say:

He is the only man I ever knew the foundation of whose spirit was love. That love made him suffer. I saw him look at the ragged, hungry prisoners at City Point, I saw him ride over the battle-field at Petersburg, the man with the hole in his forehead and the man with both arms shot away lying accusing before his eyes. I saw him enter into Richmond, walking between lanes of silent men and women who had lost their battle. I remember his face. ... And yet my memory of him is not of an unhappy man. I hear so much to-day about the President's melancholy. It is true no man could suffer more. But he was very easily amused. I have never seen a man who enjoyed more anything pleasant or funny that came his way. I think the balance between pain and pleasure was fairly struck, and in the last months when I knew him he was in love with life because he found it possible to do so much. ... I never saw evidence of faltering. I do not believe any one ever did. Prom the moment he, who was all pity, pledged himself to war, he kept straight on.

I can follow Secretary John Hay and say: He was the greatest man I have ever known—or shall ever know.

That ought to be enough to say, and yet—nothing so merely of words seems to express him. Something that he did tells so much more.

I remember one afternoon, not long before the President was shot, we were on our way to the War Department, when we passed a ragged, dirty man in army clothes, lounging just outside the White House enclosure. He had evidently been waiting to see the President, for he jumped up and went toward him with his story. He had been wounded, was just out of the hospital—he looked forlorn enough. There was something he wanted the President to do; he had papers with him. Mr. Lincoln was in a hurry, but he put out his hands for the papers. Then he sat down on the curbstone, the man beside him, and examined them. When he had satisfied himself about the matter, he smiled at the anxious fellow, reassuringly, and told him to come back the next day. Then he would arrange the matter for him. A thing like that says more than any man could express. If I could only make people see him as I did—see how simple he was with every one; how he could talk with a child so that the child could understand and smile up at him; how you would never know, from his manner to the plainest or poorest or meanest, that there was the least difference between that man and himself; how, from that man to the greatest, and all degrees between, the President could meet every man square on the plane where he stood and speak to him, man to man, from that plane—if I could do that, I would feel that I had told something of what he was. For no one to whom he spoke with his perfect simplicity ever presumed to answer him familiarly, and I never saw him stand beside any man—and I saw him with the greatest men of the day—that I did not feel there again President Lincoln was supreme. If I had only words to tell what he seemed to me!

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1939, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 80 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.