CHAPTER IX

JAPANESE HOSPITALITIES

Among Japanese virtues stands hospitality, but, until the adoption of foreign dress and customs by the court nobles, no Japanese allowed his wife to receive general visitors, or entertain mixed companies. The Japanese is, consequently, a born club-man, and makes the clubhouse a home. The Rokumeikwan, or Tokio Nobles' Club, is the most distinguished of these corporations. Its president is an imperial prince, and its members are diplomats, nobles, officials, rich citizens, and resident foreigners. The exquisite houses and gardens of the smaller, purely Japanese clubs, are perfect specimens of native architecture, decoration, and landscape gardening. By an arrangement of sliding screens, the houses themselves may afford one large room or be divided into many small ones, besides the tiny boxes in which are celebrated the rites of cha no yu, or ceremonial tea.

Their elaborate dinners, lasting for hours, with jugglers, dancers, and musicians between the courses, are very costly. Rich men display a Russian prodigality in entertaining, which was even greater in feudal times. A day or two after arriving in Japan it was my good-fortune to be a guest at one of these unique entertainments, given at the Koyokwan, or Maple Leaf Clubhouse, on the hill-side above the Shiba temples. We arrived at three o’clock, and were met at the door by a group of pretty nesans, or maids of the house, who, taking off our hats and shoes, led us, stocking-footed, down a shining corridor and up-stairs to a long, low room, usually divided into three by screens of dull gold paper. One whole side of this beautiful apartment was open to the garden beyond a railed balcony of polished cedar, and the view, across the maple-trees and dense groves of Shiba, to the waters of the Bay was enchanting. The decorations of the club-house repeat the maples that fill the grounds. The wall screens are painted with delicate branches, the ramma, or panels above the screens, are carved with them, and in the outer wall and balcony-rail are leaf-shaped openings. The dresses of the pretty nesans, the crape cushions on the floor, the porcelain and lacquer dishes, the sake bottles and their carved stands, the fans and bon-bons, all display the maple-leaf. In the tokonoma, or raised recess where the flower-vase and kakemono, or scroll picture, are displayed, and that small dais upon which the Emperor would sit if he ever came to the house, hung a shadowy painting, with a single flower in a bronze vase.

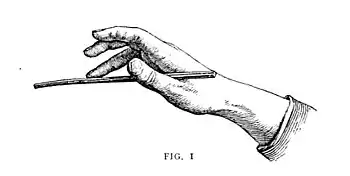

Before each guest were set the tabako bon, a tray holding a tiny hibachi with live coals lying in a cone of ashes, and a section of bamboo stem for an ash-receiver. Then came the tea and sweetmeats, inevitable prelude to all good cheer. Next the nesans set in front of each guest an ozen, or table, not four inches in height, on which stood a covered lacquered bowl containing the first course, a tiny cup of soy, or piquant bean sauce, in which to dip morsels of food, and a long envelope containing a pair of white pine chopsticks. The master of

FIG. 1

the feast broke apart his chopsticks, which were whittled in one piece and split apart for only half their length, to show that they were unused, and began a nimble play with them. In his fingers they were enchanted wands, and did his bidding promptly; in ours they wobbled, made x’s in the air, and deposited morsels in our laps

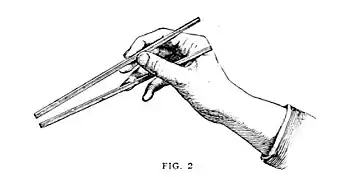

FIG. 2

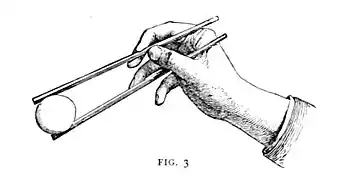

and upon the mats alternately. The nesans giggled, and the host almost forgot his Japanese decorum, but the company patiently taught us how to brace one chopstick firmly in the angle of the thumb and against the third finger. That stick is immovable, and the other, held like a pen with the thumb and first and second fingers, plays upon it, holding and letting go with a sureness and lightness hardly attained with any other implements. The supreme test of one’s skill is to lift and hold an egg, the round surface making a perfect balance and firm hold necessary, while too much force applied would cause disasters.

FIG. 3

Innumerable courses of dainty dishes followed, accompanied by cups of hot saké, which our host taught us to drink as healths, offered by each one of the company to the others in turn, rinsing, offering, filling, and raising the cup to the forehead in salutation, and emptying it in three prescribed sips. Custom even requires one to offer a health to the nesans, which they receive with a modest and charming grace.

Midway in the feast three charming girls in dark crape kimonos, strewn with bright maple-leaves, slipped the screens aside and knelt on the mats with the koto, samisen, and tsuzumi drum, on which they played a prelude of sad, slow airs. Then the gilded panels disclosed a troop of dazzling maiko in soft blue kimonos brocaded with brilliant maple-leaves and broad obis of gold brocade, the loops of their blue-black hair thrust full of golden flowers, and waving gold fans painted with gay maples. To the melancholy accompaniment of the geisha, they danced the song of the maple-leaf in measures that were only a slow gliding and changing from one perfect pose to another. Watching these radiant creatures in their graceful movements, we were even deaf to the soft booming of the temple bells at the sunset hour, and the answering croak of the mighty ravens.

These maiko and geisha, professional dancers and singers, are necessary to any entertainment, and are trained to amuse and charm the guests with their accomplishments, their wit, and sparkling conversation; lending that attraction, brightness, and charm to social life, which wives and daughters are permitted to do in the Occident. The maiko dances as soon as she is old enough to be taught the figures and to chant the poems which explain them; and when she begins to fade, she dons the soberer attire of the geisha, and, sitting on the mats, plays the accompaniments for her successors and pupils. Until this modern era, the geisha were the most highly educated of Japanese women, and many of them made brilliant marriages.

Long before the beautiful band had finished their poem and dance of the four seasons, twilight had fallen. Andons, or saucers of oil, burning on high stands inside square paper lantern frames, made Rembrandtesque effects. Everything was lost in shadow but the figures of the maiko moving over the shining mats. One tiny girl of thirteen, belonging to the house, slipped in and out with a bronze box and snuffers, and, kneeling before the andons, opened the paper doors to nip off bits of the wicks. The child, a miniature beauty, was grace itself, gentle and shy as a kitten, blushing and quaintly bowing when addressed.

It was six hours after the entrance of the tabako bons before the guests rose to depart. All the troop of maidens escorted us to the door, and after endless bows and farewells, sat on the mats In matchless tableaux, their sweet sayonaras ringing after us as our jinrikishas whirled us down the dark avenues of Shiba.

Cha no yu might well be a religious rite, from the reverence with which it is regarded by the Japanese, and a knowledge of its forms is part of the education of a member of the highest classes. Masters teach its minute and tedious forms, and schools of cha no yu, like the sects of a great faith, divide and differ. The cha no yu ceremony is hedged round with the most awesome, elaborate, and exalted etiquette of any custom in polite Japanese life. Weddings or funerals are simple affairs by comparison. The cha no yu is a complication of all social usages, and was perfected in the sixteenth century, when it was given its vogue by the Shogun Hideyoshi. Before that it had been the diversion of imperial abbots, monarchs retired from business, and other idle and secluded occupants of the charming villas and monasteries around Kioto. Hideyoshi, the Taiko, saw in its precise forms, endless rules, minutiae, and stilted conventionalities a means of keeping his daimios from conspiracies and quarrels when they came together. It was an age of buckram and behavior,_when solemnity constituted the first rule of politeness. Tea drinking was no trivial incident, and time evidently had no value. The daimios soon invested the ceremony with so much luxury and extravagance that Hideyoshi issued sumptuary laws, and the greatest simplicity in accessories was enjoined. The bowls in which the tea was made had to be of the plainest earthen-ware, but the votaries evaded the edict by seeking out the oldest Chinese or Korean bowls, or those made by some celebrated potter. Tea-rooms were to a certain size—six feet square; the entrance became a mere trap not three feet high; no servants were permitted to assist the host, and only four guests might take part in the six-hour or all-day-long ceremony. The places of the guests on the mats, with relation to the host, the door, and the tokonoma, or recess, were strictly defined. Even the conversation was ordered, the objects in the tokonoma were to be asked about at certain times, and at certain other times the tea-bowl and its accompaniments were gravely discussed. Not to speak of them at all would be as great an evidence of ill-breeding as

to refer to them at the wrong time.

The masters of cha no yu were revered above scholars and poets. They became the friends and intimates of Emperors and Shoguns, were enriched and ennobled, and their descendants receive honors to this day. Of the great schools and methods those of Senke, Yabunouchi, and Musanokoji adhere most closely to the original forms. Their first great difference is in the use of the inward or the outward sweep of the hand in touching or lifting the utensils. Upon this distinction the dilettanti separated, and the variations of the many schools of to-day arose from the original disagreement. To get some insight into a curious phase of Japanese social life, I took lessons in cha no yu of Matsuda, an eminent master of the art, presiding over the ceremonial tea rooms of the Hoishigaoka club-house in Tokio.

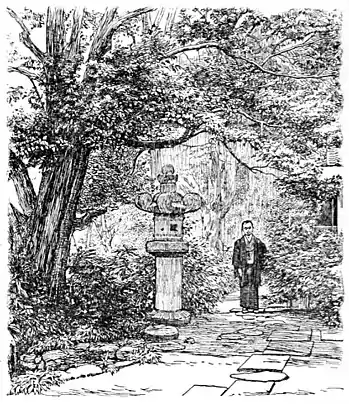

There could be no more charming place in which to study the etiquette of tea drinking, and the master was one of those mellow, gentle, gracious men of old Japan, who are the perfect flower of generations of culture and refinement in that most æsthetic country of the world. In the afternoon and evening the Hoishigaoka, on the apex of Sanno hill, is the resort of the nobles, scholars, and literary men, who compose its membership, but in the morning hours, it is all dappled shadow and quiet.

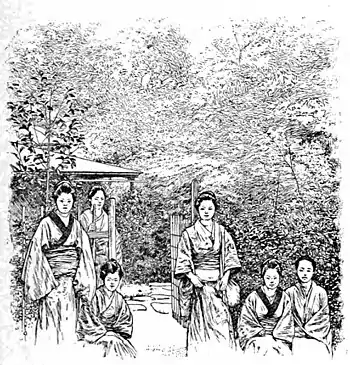

THE NESANS AT THE HOISHIGAOKA

The master was much pleased at having four foreign pupils. and all the hill side took an interest in our visits. We followed the etiquette strictly, first taking off our shoes—for one would as soon think of walking hobnailed across a piano-top, as of marring the polished woods of Japanese corridors, or the fine, soft mats of their rooms with heel-marks— and sitting on our heels, as long as our unaccustomed and protesting muscles and tendons permitted.

First, bringing in the basket of selected charcoal, with its pretty twigs of charred azalea coated with lime, Matsuda replenished the fire in the square hearth in the floor, dusted the edges with an eagle’s feather, and dropped incense on the coals. Then he placed the iron kettle, filled with fresh water from a porcelain jar, over the coals, and showed us how to fold the square of purple silk and wipe each article of the tea-service, how to scald the bowl, and to rinse the bamboo whisk. For cha no yu, tea-leaves are pounded to a fine powder, one, two, or three spoonfuls of this green flour being put in the bowl, as the guests may prefer a weak or a strong

MATSUDO, THE MASTER OF CHA NO YU

It is in the precise management of each implement, in each position of the fingers, in the deliberation and certainty of each movement, that the art of cha no yu lies, and its practice must be kept up throughout the lifetime of a devotee. Even with all the foreign fashions, the old ceremonial rites are as much in vogue with the upper classes as ever, and the youth of both sexes are carefully trained in their forms.

Much less pretentious and formal are the eel dinners with which Japanese hosts sometimes delight their foreign friends, as well as those of their own nationality. Even Sir Edwin Arnold has celebrated the delights of eels and rice at the Golden Koi, and there are other houses where the delicious dish may be enjoyed. When one enters such a tea-house, he is led to a tank of squirming fresh-water eels, and in all seriousness bidden to point out the object of his preference. Uncertain as the lottery seems, the cook, who stands by with a long knife in hand, quickly understands the choice made, and seizing the wriggling victim, carries it off to some sacrificial block in the kitchen. An eel dinner begins with eel-soup, and black eels and white eels succeed one another in as many relays as one may demand. The fish are cut in short sections, split and flattened, and broiled over charcoal fires. Black eels, so called, are a rich dark brown in reality, and the color is given them by dipping them in soy before broiling; and white eels are the bits broiled without sauces. Laid across bowls of snowy rice, the eels make as pretty a dish as can be served one, and many foreigners besides the appreciative English poet have paid tribute to their excellence. An eel dinner in a river-bank tea-house, with a juggler or a fow maiko to enliven the waits between the courses, is most delightful of Tokio feasts.