CHAPTER XXV

THE PALACES AND CASTLE

Kioto remains faithful to its traditions, and yields but slowly to the foreign fashions which absorb Tokio. Tokio has nineteenth-century political troubles, even demagogues and hare-brained students, that unruly young element, the soshi, keep it in a state of agitation, and sometimes appeal to the old two-handed sword, the dagger, and the cowardly bomb. But Kioto, devoted to its old order, maintains the reign of peace, while the arts flourish.

For the thousand years during which this ancient Saikio remained the home of the Emperor, and of his nominal subject, the Shogun, its western half was crowded with the life centering about the two rulers. The ancient Emperors were hidden within the vast palace enclosure, the centre of other large demesnes, whose yellow walls were marked with the five horizontal white lines which indicate imperial possessions. This collection of palaces and the yashikis of the kuges, or court nobles, were then surrounded by one exterior wall and moat, making an immense imperial reservation—a small isolated city. Within a few years this exterior wall has been destroyed, streets have been opened, and much of the space has been turned into a public park. The imperial palace buildings cover ten acres of ground, and are surrounded by twenty-six acres of ornamental park. In each of the four yellow outer walls is a richly roofed and gabled gate-way, as stately as a temple, the ends of the beams, the ridges, and eaves decorated with golden chrysanthemum crests. The great gate, opened only for the Emperor and his train, and through whose central passage only the sacred being himself may be borne, faces south, as does the throne, in accordance with the old superstitions of the East. The evil influences always threatening from the north-east are guarded against by many temples beyond that side of the palace.

In these days of departed greatness only the Daidokoro Mon (the august kitchen gate), a fine gabled structure in the western wall, is used. After the visitor presents the elaborate official permit, obtained by his legation from the Imperial Household Department of Tokio, and stamped after a personal inspection of the holder by the Kioto bureau of that department, there is much running to and fro of ancient officials, much restamping and recording, before he is led through the precinct by an attendant. Even with this guarantee, the severe and stately old guardians, in their ancient dress and tonsure, seem to look on the intruder with suspicion.

The Japanese gosho is not exactly translated by the word “palace,” and is merely a greater yashiki, or spread-out house, constituting the sovereign’s residence. This gosho consists of so many separate roofed, one-story wooden buildings as to make a small village. Each room, or suite of rooms, occupies a distinct building, its outside gallery or veranda forming the corridor, and its sliding screens the inner walls. Each building has the great sweeping roof of a temple, the belief in the divinity of the Emperor, and his headship of the Shinto faith, requiring that his actual dwelling should be a temple, rigidly simple as a Shinto shrine, with thatched roof and unpainted woods. These clustered houses are the survival of the old nomad camps of Asia, as the upward curving gables of the roof are a permanent form of their sagging tent-tops. The palace has suffered from many fires, the last occurring in 1854, but each rebuilding has followed the original models, and the gosho looks just as it did centuries ago. The same straw mats, open charcoal braziers, and loose saucers of oil in paper lamp-frames, inviting a conflagration there as in the humblest Japanese home.

The walk around the outer galleries and connecting corridors takes half an hour, and one must go stocking-footed, or in the curious slippers furnished by the guardians. In summer the recessed and sunless apartments are cool and dim, but winter makes them bitterly cold and forlorn. Except for two thrones, there is nothing to be called furniture in the palace. The silk-bordered mats of the floor, the paintings on the sliding screens, the fine metal plates on all the wood-work, the irregularly-shelved recesses, quaint windows, curious lattices, and richly-panelled ceilings constitute its adornments. All the wonderful kakemonos, vases, and curios were stored in godowns when the Emperor left Kioto, and the seals have not since been broken. On the screens in the private apartments are many autograph poems, written by court poets or imperial improvisators. The tea-rooms and the garden tea-houses show how important were the long-drawn ceremonies of cha no yu in those leisurely days of the past.

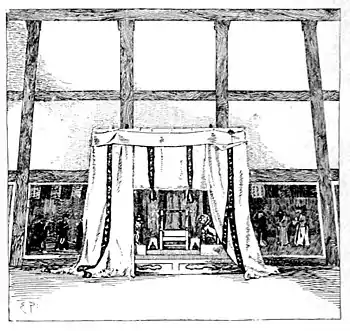

The courts surrounding the state apartments are sanded quadrangles, their surfaces scratched over in fine patterns by the gardeners’ bamboo rakes for the easy detection of strange footprints. In the court-yard before the old audience hall a cherry-tree, a wild orange-tree, and a sacred bamboo, all emblematic, grow at either side of the broad steps. In the middle of the wide, temple-like apartment commanding this court stands the sacred white throne of past centuries, a square tent or canopy of white silk, with rich red borders at the edges of the overlapping curtains. Two antique Chinese dogs guard the throne. On New-year’s Day, and at rare intervals when the Emperor gave audience to his vassal jailer, the Shogun, he sat on a silk cushion within the closed tent, and only his voice was heard, speaking in the quavering, long-drawn tones still used by the actors in the No dance. The imperial princes stood at either side of the throne, the kugé and officials of the highest rank knelt on the steps, and the lowest officials in attendance, the jige or “down to the earth” subjects, prostrated themselves on the sands of the court, while the mournful and muffled tones of the sacred voice sounded.

When the Emperor gave his first audiences after the Restoration, in 1868, he occupied a newer throne in the Shishinden, a large audience hall with a lofty ceiling supported by round wooden columns. On the lower part of the rear wall are some very old screens painted with groups of Chinese and Korean sages. The floor is of polished cedar, and the throne is like that of his ancestors, but with the curtains rolled up from the front and two sides. It stands on a dais, guarded by the Chinese dogs brought as trophies from Korea, and holds

THE THRONE OF 1868.

within it a simple lacquered chair, with lacquer stands for the sacred sword and seal. After those audiences of 1868 the Emperor travelled to Tokio in a gold-lacquered norimon, or closed litter, guarded by a train clad in the picturesque dress and armor of centuries before, and equipped with curious old weapons. He, himself, wore voluminous silk robes and a stiff lacquer hat, and the faithful kugés were attired in gorgeous brocades and silks. When the Emperor and court returned to Kioto in 1878, to open the railway to the seaport of Hiogo-Kobé, he was dressed like a European sovereign, alighted publicly from his railway car, and drove to the palace in a smart brougham, escorted by troops with western uniforms and weapons.

The Shiro, or Nijo castle, half a mile south of the palace, where the Shoguns flaunted their wealth and power, is a splendid relic of feudal days. The broad moat, drawbridge, strong walls, and tower- topped gate-ways and angles date from the middle of the sixteenth century. The great gate-way inside the first wall is a mass of elaborate metal ornament, from the sockets of the corner posts to the ridge-pole, but the many trefoils of the Tokugawas have been everywhere covered by the imperial chrysanthemum. All the rooms, but especially the two splendid audience- chambers, with a broad dais before each tokonoma, are marvels of decorative art, rich in gilded screens, with exquisite paintings and fine metal work, wonderfully carved ramma, and sunken ceiling panels, ornamented with flower circles, crests, and geometric designs. But, alas! a hideous Brussels carpet, a round centre-table, and a ring of straight-backed chairs have crowded their vulgar way into these stately rooms, as into every government building and office, large shop, and tea-house in Kioto.

The Shoguns had the Kinkakuji, the Ginkakuji, and other suburban villas to which they might resort, and in which many of them ended their days as abbots and priests. The Emperors had only the exquisite Shugakuin gardens at the foot of Mount Hiyeizan for their pleasurings, until the Restoration gave all such rebel property to the crown. The Kinkakuji (the gold-covered pavilion) and the Ginkakuji (the silver-covered pavilion) stand at opposite sides of the city, each surrounded with landscape-gardens, from which nearly all Japanese gardens are copied. Both are as old as the Ashikaga Shoguns, and both are now monasteries. The Kinkakuji is the larger, and was even more splendid before it was despoiled of so many rare and historic stones and garden ornaments, but the place is still a paradise. Yoshimitsu, third of the Ashikaga Shoguns, built the Kinkakuji, and thither the great Ashikaga retired to end his life. This refuge figures in the many novels of the time of the Ashikagas, when the War of the Chrysanthemums, the Japanese War of the Roses, raged, and the Emperors with the kuges suffered actual want and privation. The memory of this third Ashikaga is abhorred, because he paid tribute to China and accepted from that country in return the title of “King of Japan;” but he so fostered luxury and art that some of his other sins are forgiven him. The pretty little palace at the lake’s edge, with its golden roof and lacquered walls, has successfully withstood the centuries, and is still intact. In the monastery buildings near the gate-way are shown many wonderful kakemonos and screens, and in one court is a pine-tree trained in the shape of a junk, hull, mast, and sail perfectly reproduced in the feathery, living green needles of the tree. It is most interesting to see how the patient gardeners have bent, interlaced, tied, weighted down, and propped up the limbs and twigs to produce this model, with the slow labor of a century.

To the Ginkakuji retired the dignified Yoshimasa, eighth of the Ashikaga Shoguns, to found a monastery and to meditate, until with Murata Shinkio, the priest, and Soami, the painter, he evolved the minute and elaborate ceremonies of cha no yu. The weather-beaten boards and finely thatched roof of the first ceremonial tea-house in Japan, built before Columbus set sail for the Zipangu of Marco Polo, are greatly revered by Japanese visitors. Beautiful is the way to the Ginkakuji, past the high walls and gate-ways of monasteries, past the towering gates of countless temples, up their long shaded avenues, and on by bamboo groves and terraced rice fields. You buy wooden admission tickets for ten sen, which you give to a little acolyte, who opens the inner gate-way. This chisai bonze san (small priest) might have been twelve years old, but looked not more than five when I first knew him, and from shaven head to sandaled foot he was a Buddhist priest in miniature. This Shinkaku, leading the way to the lake with solemn countenance and hands primly clasped before him, suddenly broke forth into a wild, sing-song chant, which recited the names of the donors of the rocks and lanterns to the great Ashikaga Yoshimasa. He made us take off our shoes and creep up the steep and ancient stair-way of the Ginkakuji to see a blackened and venerable image of Amida. Morning, noon, and night service is said before the altar in the little old temple by the lake, and this small priest burns incense, passes the sacred books, and assists the wrinkled and aged priests in the observances of the Zen sect of Buddhists. Back of the monastery buildings is a lotus pond, where the great pink flower-cups fill the air with perfume, and every morning are set fresh before Buddha’s shrine.

Going westward from Kioto the traveller crosses rice fields, skirts a long bamboo hedge, and comes to the summer palace of Katsura no Miya, a relic of the Taiko’s days. An aunt of the Emperor occupied it until her recent decease, and to that is probably due its perfect preservation. An ancient samurai with shaven crown and silken garments receives, with a dozen bows, the handful of official papers that constitute a permit to visit the imperial demesne. Dropping his shoes at the steps, the visitor wanders through a labyrinth of little rooms, each exquisite, simple, and charming, with its golden screens and gold-flecked ceilings. The irregularly shelved recesses, the chigai dana of each room, the ramma, the lattices and windows, are perfect models of Japanese taste and art; and the Taiko’s crest is wrought in silver, gold, and bronze on all the mountings, and is painted and carved everywhere. The open rooms look upon a lovely garden, and paths of flat-topped stones lead through the tiny wilderness of lake, forest, thicket, and stream; over old stone bridges, stained and lichen-covered, to picturesque tea-houses and pavilions, overhanging the lake. Stone Buddhas and stone pagodas stand in shadowy places, and stone lanterns under dwarf pine-trees are reflected in the curve of every tiny bay. It is an ideal Japanese garden, with the dew of a midsummer morning on all the spider webs, and only the low note of the grasshoppers to break the stillness.

Although all tourists spend a day in shooting the rapids of the Oigawa, it seems to me a waste of precious Kioto time and a performance out of harmony with the spirit of the place, although in May the blooming azaleas cause that wild and narrow canon to blaze with color. The flat-bottomed boats dart through the seven-mile gorge and dash from one peril of shipwreck to another, just saved by a dextrous touch of the boatmen’s poles, which fit into holes in the rocks that they themselves have worn. The flooring of the boats is so thin as to rise and fall with the pressure of the water, in a way that seems at first most alarming. The passage ends at Arashiyama, a steep hill clothed with pine, maple, and cherry-trees, which in cherry-blossom time, or in autumn, is the great resort of all Kioto, whose pleasurings there form the theme of half the geisha’s songs and the accompanying dances. From the tea-house on the opposite bank the abrupt mountain-side shows a mat of densest foliage. A torii at the river's edge, stone steps and lines of lanterns lead to a temple on the summit, and down through the forest float the soft, slow beats of a temple-bell. The tea-house is famous for its fish-dinners, where tai, fresh from the cool, green river, are cooked as only the Japanese can cook them, and the lily bulbs, rice sandwiches, omelettes, and sponge-cake are so good that the place is always crowded.

Katsura no Miya is just below Arashiyama, and after one morning spent in the little palace, with its restful shade and stillness, our half-naked coolies ran with us through the glaring sunlight to the tea-house beside the cool waters of the Oigawa. They barely waited for us to step out of the jinrikishas before they plunged, laughing and frolicking, down the bank and leaped into the river, splashing and swimming there like so many frogs. They had run ten miles that morning, half of the way under a baking sun, the perspiration streaming from their bodies, and they plunged into the river as they were, taking off their one cotton garment and washing it, while they cooled themselves in the rushing waters. Then, lying down quite uncovered in their own quarters of the tea-house, they ate watermelon and cucumber, drank tea and smoked, until they dropped asleep in the scorching noonday of a cholera summer. In the late afternoon, when it was time to begin the long ride back to Maruyama, they limped out to us, lame and stiff in every joint and muscle, coughing and croaking like ravens. We felt that they must die in the shafts, but exercise soon relieved the cramped and stiffened limbs, and they trotted on as nimbly as ever over the hills to Kioto.

The coolie and his ways are matters of much interest to foreigners, but after a time one ceases to be amazed at their endurance or their recklessness. After the most violent exercise, ninsoku, the coolie, will take off his one superfluous garment and sit in summer ease in his decorated skin. Back, breast, arms, and thighs are often covered with elaborate tattooed pictures in blue, red, and black on the raw-umber ground. His philosophy of dress is a simple one. When the weather is too hot to wear clothes they are left off, and a wisp of straw for the feet, a loin-cloth, and a huge flat hat, a yard in diameter, weighing less than a feather, are enough for him. When there is no money to buy raiment he tattoos himself with gorgeous pictures, which he would never hide were there not watchful policemen and Government laws to compel him into some scanty covering.

The diet of these coolies seems wholly insufficient for the tremendous labor they perform—rice, pickled fish, fermented radish, and green tea affording the thin nutriment of working-days. Yet the most splendid specimens of physical health are reared and kept in prize-fighting condition on what would reduce a foreigner to invalidism in a week. I remember that while resting one hot morning under Shinniodo’s great gate-way, my coolie, who by an unusually early start had been interrupted in his breakfast of one green apple, asked for some tea-money. I watched the hungry pony while he treated his companions to a substantial repast of tea and watermelon. Strengthened and recuperated, he came back, shouldered camera and tripod, and as he walked down the hot flagging, complacently picked his teeth with the sharp point of one tripod stick—a toothpick four feet long!