BRIDGE.

This is a recent development of the grand old game of Whist. Though differing widely in many particulars from its prototype, it is still essentially Whist, the innovations, while introducing a new speculative element, affording even larger opportunities for the exercise of the judgment and skill which Whist proper demands; and the best proof of its merit lies in the fact that even by the "old stagers" of the London clubs it is now generally played in preference to the classic game.

The main elements of novelty in Bridge, as distinguished from Whist, may be classed under the following heads:—

1. The manner of deciding the trump suit.

2. Different values of tricks and honours according to the suit made trumps.

3. Licence to each party in turn to double and re-double the normal value of tricks.

4. The dealer playing two hands, his partner becoming a "dummy."

Before proceeding to the Laws in detail, it should be premised that Bridge, like ordinary Whist, is played by four persons, two against two, with the full pack of fifty-two cards (two such packs being used alternately). The players cut for partners and for deal; the cards are shuffled, cut, and dealt in the usual way, thirteen to each player; but no card is turned up, the trump suit being named by the dealer, or by his partner, as hereafter explained.

Before perusing the following general remarks, the reader should study the Club code of Laws, which will be found at the end of this chapter, and which contains full particulars as to naming the trump suit, doubling and re-doubling, revoke penalty, mode of reckoning up points, &c.

The Score in Actual Practice.

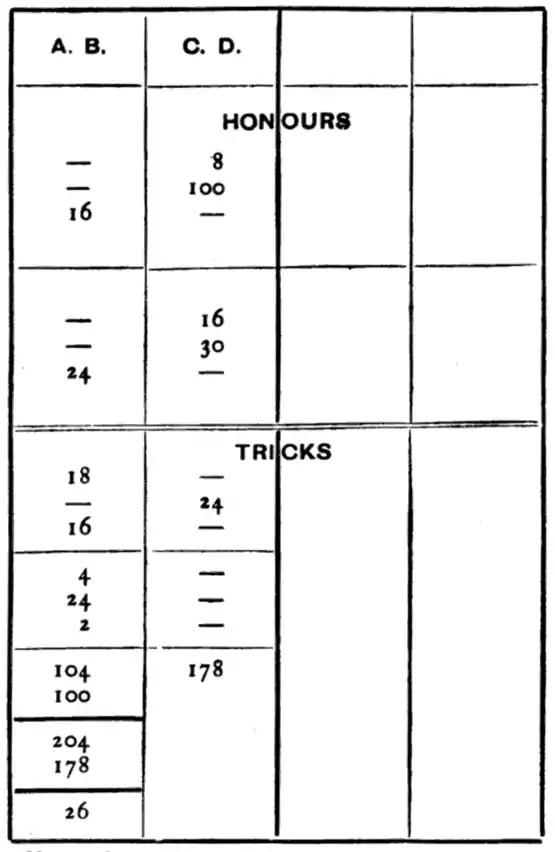

This is usually kept upon a scoring block, ruled as shown upon the following page. Each column is intended to receive the score of one rubber. It will be observed that the column is divided midway by a horizontal line. The portion below this is for recording the value of the tricks won; the portion above for the scoring of honours and the other subsidiary elements affecting the ultimate value of the rubber.

A practical example will best illustrate the working of the plan. A and B, we will suppose, are playing against C and D. Diamonds have been declared to be trumps, and A and B have won in the first deal nine tricks. The value of each trick, when diamonds are trumps, being 6 points, A and B score in their own column, immediately below the central line, 18. They have also together held four honours, value in diamonds, 24. They accordingly mark 24 above the line.

Bridge Scoring Block.

- Note.—Scoring Blocks of this pattern, but usually of larger size, are issued by all card-making stationers at low prices.

The next deal is played sans atout. C and D are the winners by two tricks, and between them hold three aces. The value of the two tricks is 24, which is scored below the line, and the value of the three aces 30, which is scored above the line.

In the third deal, hearts are trumps. A and B win two tricks, value 16 points. This, added to their previous 18, makes them 32, and therefore gives them the game. But C and D hold three honours, value in hearts 16: these they score above their previous 30. The points are not yet added up, but a pencil line is drawn above and below the scores of both parties, to indicate that they represent a completed game.

In the next deal, clubs are trumps. A and B win the odd trick, value 4 points. They have also four honours (divided), value in clubs 16.

The next hand is played sans atout. A and B win two tricks, value 24, but D holds four aces, value 100.

In the next hand, spades are trumps, and A and B make the odd trick, value 2 points. This makes them game, giving them the rubber as well, but C and D hold between them four honours, value in spades 8, which number is accordingly placed to their credit.

We are now in a position to assess the value of the rubber. Each column is added up. The total of A and B's score is 104, while that of C and D is 178. But the 100 points for the rubber have yet to be taken into consideration. These are accordingly added to the score of A and B, bringing it up to 204. From this total is deducted the 178 standing to the credit of C and D, and the difference, 26, is the number of points by which A and B are the gainers.

As the points at Bridge frequently run into high figures, it is as well to keep their individual value small, or a loser may find himself let in for an amount which he had not intended risking.

Hints for Play.

So far as the science of the game is concerned, the main point, in so far as it differs from Whist, is to be able to judge correctly what suit should be made trumps; whether to play without trumps; or, lastly, whether to pass the option to one's partner. Hands are, of course, capable of almost infinite variety, and it is difficult to lay down rules which shall govern all cases. The novice may, however, safely take to heart the following maxims:—

1. Holding four aces, the dealer plays sans atout, inasmuch as he thereby secures four certain tricks, besides one hundred for his aces.

2. Holding three aces, he should do likewise, unless he has a strong red suit, giving assurance of a high score without risk, while the No-trump call involves dangerous weakness in one suit. In this case, the strong red suit should be declared.

3. Early in the game, if he cannot safely declare No-trumps or a red suit, and is not exceptionally strong in clubs, he should pass the option to his partner.

4. When the score of the dealer and his partner is approaching game, if the dealer can make game a certainty by declaring a black suit trumps, he should usually do so.

For more detailed advice as to Bridge tactics, the reader may be referred to two handy little works by W. Dalton, entitled Bridge at a Glance and Bridge Abridged, published by Messrs. De la Rue & Co. By the courtesy of these gentlemen, we are enabled to reprint the authoritative Laws of the game, as revised by a joint committee of the Portland and Turf Clubs. It will be observed that they follow very closely the Laws of Whist; but the special features of Bridge have been minutely considered and provided for, and a careful study of the Laws will form the best possible introduction to a knowledge of the game.

THE LAWS OF BRIDGE (1904).

(Reprinted, by permission, verbatim from the Club Code.)

The Rubber.

1. The Rubber is the best of three games. If the first two games be won by the same players, the third game is not played.

Scoring.

2. A game consists of thirty points obtained by tricks alone, exclusive of any points counted for Honours, Chicane, Or Slam.

3. Every hand is played out, and any points in excess of the thirty points necessary for the game are counted.

4. Each trick above six counts two points when spades are trumps, four points when clubs are trumps, six points when diamonds are trumps, eight points when hearts are trumps, and twelve points when there are no trumps.

5. Honours consist of ace, king, queen, knave, and ten of the trump suit. When there are no trumps they consist of the four aces.

6. Honours in trumps are thus reckoned:

If a player and his partner conjointly hold—

- I. The five honours of the trump suit, they score for honours five times the value of the trump suit trick.

- II. Any four honours of the trump suit, they score for honours four times the value of the trump suit trick.

- III. Any three honours of the trump suit, they score for honours twice the value of the trump suit trick.

If a player in his own hand holds—

- I. The five honours of the trump suit, he and his partner score for honours ten times the value of the trump suit trick.

- II. Any four honours of the trump suit, they score for honours eight times the value of the trump suit trick. In this last case, if the player's partner holds the fifth honour, they also score for honours the single value of the trump suit trick.

The value of the trump suit trick referred to in this Law is its original value, e.g. two points in spades and six points in diamonds; and the value of honours is in no way affected by any doubling or re-doubling that may take place under Laws 53 to 56.

7. Honours, when there are no trumps, are thus reckoned:

If a player and his partner conjointly hold—

- I. The four aces, they score for honours forty points.

- II. Any three aces, they score for honours thirty points.

If a player in his own hand holds—

- The four aces, he and his partner score for honours one hundred points.

8. Chicane is thus reckoned:

- If a player holds no trump, he and his partner score for Chicane twice the value of the trump suit trick. The value of Chicane is in no way affected by any doubling or re-doubling that may take place under Laws 53 to 56.

9. Slam is thus reckoned:

If a player and his partner make, independently of any tricks taken for the revoke penalty—

- I. All thirteen tricks, they score for Grand Slam forty points.

- II. Twelve tricks, they score for Little Slam twenty points.

10. Honours, Chicane, and Slam are reckoned in the score at the end of the rubber.

11. At the end of the rubber, the total scores for tricks, honours, Chicane and Slam obtained by each player and his partner are added up; one hundred points are added to the score of the winners of the rubber, and the difference between the two scores is the number of points won, or lost, by the winners of the rubber.

12. If an erroneous score affecting tricks be proved, such mistake may be corrected prior to the conclusion of the game in which it occurred, and such game is not concluded until the last card of the following deal has been dealt, or, in the case of the last game of the rubber, until the score has been made up and agreed.

13. If an erroneous score affecting honours, Chicane, or Slam be proved, such mistake may be corrected at any time before the score of the rubber has been made up and agreed.

Cutting.

14. The ace is the lowest card.

15. In all cases, every player must cut from the same pack.

16. Should a player expose more than one card, he must cut again.

Formation of Table.

17. If there are more than four candidates, the players are selected by cutting, those first in the room having the preference. The four who cut the lowest cards play first, and again cut to decide on partners; the two lowest play against the two highest; the lowest is the dealer, who has choice of cards and seats, and, having once made his selection, must abide by it.

18. When there are more than six candidates, those who cut the two next lowest cards belong to the table, which is complete with six players; on the retirement of one of those six players, the candidate who cut the next lowest card has a prior right to any after-comer to enter the table.

19. Two players cutting cards of equal value, unless such cards are the two highest, cut again; should they be the two lowest, a fresh cut is necessary to decide which of those two deals.

20. Three players cutting cards of equal value cut again; should the fourth (or remaining) card be the highest, the two lowest of the new cut are partners, the lower of those two the dealer; should the fourth card be the lowest, the two highest are partners, the original lowest the dealer.

Cutting Out.

21. At the end of a rubber, should admission be claimed by any one, or by two candidates, he who has, or they who have, placed a greater number of consecutive rubbers than the others is, or are, out; but when all have played the same number, they must cut to decide upon the out-goers; the highest are out.

Entry and Re-entry.

22. A candidate, whether he has played or not, can join a table which is not complete by declaring in at any time prior to any of the players having cut a card, either for the purpose of commencing a fresh rubber or of cutting out.

23. In the formation of fresh tables, those candidates who have neither belonged to nor played at any other table have the prior right of entry; the others decide their right of admission by cutting.

24. Any one quitting a table prior to the conclusion of a rubber may, with consent of the other three players, appoint a substitute in his absence during that rubber.

25. A player joining one table, whilst belonging to another, loses his right of re-entry into the latter, and takes his chance of cutting in, as if he were a fresh candidate.

26. If any one break up a table, the remaining players have the prior right to him of entry into any other; and should there not be sufficient vacancies at such other table to admit all those candidates, they settle their precedence by cutting.

Shuffling.

27. The pack must neither be shuffled below the table, nor so that the face of any card be seen.

28. The pack must not be shuffled during the play of the hand.

29. A pack, having been played with, must neither be shuffled by dealing it into packets, nor across the table.

30. Each player has a right to shuffle once only (except as provided by Law 33) prior to a deal, after a false cut, or when a new deal has occurred.

31. The dealer's partner must collect the cards for the ensuing deal, and has the first right to shuffle that pack.

32. Each player, after shuffling, must place the cards, properly collected and face downwards, to the left of the player about to deal.

33. The dealer has always the right to shuffle last; but should a card or cards be seen during his shuffling, or whilst giving the pack to be cut, he may be compelled to re-shuffle.

The Deal.

34. Each player deals in his turn; the order of dealing goes to the left.

35. The player on the dealer's right cuts the pack, and, in dividing it, must not leave fewer than four cards in either packet; if in cutting, or in replacing one of the two packets on the other, a card be exposed, or if there be any confusion of the cards, or a doubt as to the exact place in which the pack was divided, there must be a fresh cut.

36. When a player, whose duty it is to cut, has once separated the pack, he cannot alter his intention; he can neither re-shuffle nor re-cut the cards.

37. When the pack is cut, should the dealer shuffle the cards, the pack must be cut again.

38. The fifty-two cards shall be dealt face downwards. The deal is not completed until the last card has been dealt face downwards. There is no misdeal.

A New Deal.

39. There must be a new deal—

- I. If, during a deal, or during the play of a hand, the pack be proved to be incorrect or imperfect.

- II. If any card be faced in the pack.

- III. Unless the cards are dealt into four packets, one at a time and in regular rotation, beginning at the player to the dealer's left.

- IV. Should the last card not come in its regular order to the dealer.

- V. Should a player have more than thirteen cards, and any one or more of the others less than thirteen cards.

- VI. Should the dealer deal two cards at once, or two cards to the same hand, and then deal a third; but if, prior to dealing that card, the dealer can, by altering the position of one card only, rectify such error, he may do so.

- VII. Should the dealer omit to have the pack cut to him, and the adversaries discover the error prior to the last card being dealt, and before looking at their cards; but not after having done so.

40. If, whilst dealing, a card be exposed by either of the dealer's adversaries, the dealer or his partner may claim a new deal. A card similarly exposed by the dealer or his partner gives the same claim to each adversary. The claim may not be made by a player who has looked at any of his cards. If a new deal does not take place, the exposed card cannot be called.

41. If, in dealing, one of the last cards be exposed, and the dealer completes the deal before there is reasonable time to decide as to a fresh deal, the privilege is not thereby lost.

42. If the dealer, before he has dealt fifty-one cards, look at any card, his adversaries have a right to see it, and may exact a new deal.

43. Should three players have their right number of cards—the fourth have less than thirteen, and not discover such deficiency until he has played any of his cards, the deal stands good; should he have played, he is as answerable for any revoke he may have made as if the missing card or cards had been in his hand; he may search the other pack for it, or them.

44. If a pack, during or after a rubber, be proved incorrect or imperfect, such proof does not alter any past score, game, or rubber; that hand in which the imperfection was detected is null and void; the dealer deals again.

45. Any one dealing out of turn, or with the adversary's cards, may be stopped before the last card is dealt, otherwise the deal stands good, and the game must proceed as if no mistake had been made.

46 A player can neither shuffle, cut, nor deal for his partner without the permission of his opponents.

Declaring Trumps.

47. The dealer, having examined his hand, has the option of declaring what suit shall be trumps, or whether the hand shall be played without trumps. If he exercise that option, he shall do so by naming the suit, or by saying "No trumps."

48. If the dealer does not wish to exercise his option, he may pass it to his partner by saying "I leave it to you, Partner," and his partner must thereupon make the necessary declaration, in the manner provided in the preceding Law.

49. If the dealer's partner make the trump declaration without receiving permission from the dealer, the eldest hand may demand:

- I. That the declaration so made shall stand.

- II. That there shall be a new deal.

But if any declaration as to doubling or not doubling shall have been made, or if a new deal is not claimed, the declaration wrongly made shall stand. The eldest hand is the player on the left of the dealer.

50. If the dealer's partner pass the declaration to the dealer, the eldest hand may demand:

- I. That there shall be a new deal.

- II. That the dealer's partner shall himself make the declaration.

51. If either of the dealer's adversaries makes the declaration, the dealer may, after looking at his hand, either claim a fresh deal or proceed as if no such declaration had been made.

52. A declaration once made cannot be altered, save as provided above.

Doubling and Re-doubling.

53. The effect of doubling and re-doubling, and so on, is that the value of each trick above six is doubled, quadrupled, and so on.

54. After the trump declaration has been made by the dealer or his partner, their adversaries have the right to double. The eldest hand has the first right. If he does not wish to double, he shall say to his partner, "May I lead?" His partner shall answer, "Yes," or "I double."

55. If either of their adversaries elect to double, the dealer and his partner have the right to re-double. The player who has declared the trump shall have the first right. He may say, "I re-double," or "Satisfied." Should he say the latter, his partner may re-double.

56. If the dealer or his partner elect to re-double, their adversaries have the right to again double. The original doubler has the first right.

57. If the right-hand adversary of the dealer double before his partner has asked "May I lead?" the declarer of the trump shall have the right to say whether or not the double shall stand. If he decide that the double shall stand, the process of re-doubling may continue as described in Laws 55, 56, 58.

58. The process of re-doubling may be continued until the limit of 100 points is reached—the first right to continue the re-doubling on behalf of a partnership belonging to that player who has last re-doubled. Should he, however, express himself satisfied, the right to continue the re-doubling passes to his partner. Should any player re-double out of turn, the adversary who last doubled shall decide whether or not such double shall stand. If it is decided that the re-double shall stand, the process of re-doubling may continue as described in this and foregoing Laws (55 and 56). If any double or re-double out of turn be not accepted, there shall be no further doubling in that hand. Any consultation between partners as to doubling or re-doubling will entitle the maker of the trump or the eldest hand, without consultation, to a new deal.

59. If the eldest hand lead before the doubling be completed, his partner may re-double only with the consent of the adversary who last doubled; but such lead shall not affect the right of either adversary to double.

60. When the question, "May I lead?" has been answered in the affirmative, or when the player who has the last right to continue the doubling expresses himself satisfied, the play shall begin.

61. A declaration once made cannot be altered.

Dummy.

62. As soon as a card is led, whether in or out of turn, the dealer's partner shall place his cards face upwards on the table, and the duty of playing the cards from that hand, which is called Dummy, and of claiming and enforcing any penalties arising during the hand, shall devolve upon the dealer, unassisted by his partner.

63. After exposing Dummy, the dealer's partner has no part whatever in the game, except that he has the right to ask the dealer if he has none of the suit in which he may have renounced. If he call attention to any other incident in the play of the hand, in respect of which any penalty might be exacted, the fact that he has done so shall deprive the dealer of the right of exacting such penalty against his adversaries.

64. If the dealer's partner, by touching a card, or otherwise, suggest the play of a card from Dummy, either of the adversaries may, but without consulting with his partner, call upon the dealer to play or not to play the card suggested.

65. When the dealer draws a card, either from his own hand or from Dummy, such card is not considered as played until actually quitted.

66. A card once played, or named by the dealer as to be played from his own hand or from Dummy, cannot be taken back, except to save a revoke.

67. The dealer's partner may not look over his adversaries' hands, nor leave his seat for the purpose of watching his partner's play.

68. Dummy is not liable to any penalty for a revoke, as his adversaries see his cards. Should he revoke, and the error not be discovered until the trick is turned and quitted, the trick stands good.

69. Dummy being blind and deaf, his partner is not liable to any penalty for an error whence he can gain no advantage. Thus, he may expose some, or all of his cards, without incurring any penalty.

Exposed Cards.

70. If after the deal has been completed, and before the trump declaration has been made, either the dealer or his partner expose a card from his hand, the eldest hand may claim a new deal.

71. If after the deal has been completed, and before a card is led, any player shall expose a card, his partner shall forfeit any right to double or re-double which he would otherwise have been entitled to exercise; and in the case of a card being so exposed by the leader's partner, the dealer may, instead of calling the card, require the leader not to lead the suit of the exposed card.

Cards liable to be Called.

72. All cards exposed by the dealer's adversaries are liable to be called, and must be left face upwards on the table; but a card is not an exposed card when dropped on the floor, or elsewhere below the table.

73. The following are exposed cards:—

- I. Two or more cards played at once.

- II. Any card dropped with its face upwards, or in any way exposed on or above the table, even though snatched up so quickly that no one can name it.

74. If either of the dealer's adversaries play to an imperfect trick the best card on the table, or lead one which is a winning card as against the dealer and his partner, and then lead again, without waiting for his partner to play, or play several such winning cards, one after the other, without waiting for his partner to play, the latter may be called on to win, if he can, the first or any other of those tricks, and the other cards thus improperly played are exposed cards.

75. Should the dealer indicate that all or any of the remaining tricks are his, he may be required to place his cards face upwards on the table; but they are not liable to be called.

76. If either of the dealer's adversaries throws his cards on the table face upwards, such cards are exposed, and liable to be called by the dealer.

77. If all the players throw their cards on the table face upwards, the hands are abandoned, and the score must be left as claimed and admitted. The hands may be examined for the purpose of establishing a revoke, but for no other purpose.

78. A card detached from the rest of the hand of either of the dealer's adversaries, so as to be named, is liable to be called; but should the dealer name a wrong card, he is liable to have a suit called when first he or his partner have the lead.

79. If a player, who has rendered himself liable to have the highest or lowest of a suit called, or to win or not to win a trick, fail to play as desired, though able to do so, or if when called on to lead one suit, lead another, having in his hand one or more cards of that suit demanded, he incurs the penalty of a revoke.

80. If either of the dealer's adversaries lead out of turn, the dealer may call a suit from him or his partner when it is next the turn of either of them to lead, or may call the card erroneously led.

81. If the dealer lead out of turn, either from his own hand or from Dummy, he incurs no penalty; but he may not rectify the error after the second hand has played.

82. If any player lead out of turn, and the other three have followed him, the trick is complete, and the error cannot be rectified; but if only the second, or the second and third, have played to the false lead, their cards, on discovery of the mistake, are taken back; and there is no penalty against any one, excepting the original offender, and then only when he is one of the dealer's adversaries.

83. In no case can a player be compelled to play a card which would oblige him to revoke.

84. The call of a card may be repeated until such card has been played.

85. If a player called on to lead a suit have none of it, the penalty is paid.

Cards played in Error, or not played to a Trick.

86. Should the third hand not have played, and the fourth play before his partner, the latter (not being Dummy or his partner) may be called on to win, or not to win, the trick.

87. If any one (not being Dummy) omit playing to a former trick, and such error be not discovered until he has played to the next, the adversaries may claim a new deal; should they decide that the deal stand good, or should Dummy have omitted to play to a former trick, and such error be not discovered till he shall have played to the next, the surplus card at the end of the hand is considered to have been played to the imperfect trick, but does not constitute a revoke therein.

88. If any one play two cards to the same trick, or mix a card with a trick to which it does not properly belong, and the mistake be not discovered until the hand is played out, he (not being Dummy) is answerable for all consequent revokes he may have made. If, during the play of the hand, the error be detected, the tricks may be counted face downwards, in order to ascertain whether there be among them a card too many: should this be the case they may be searched, and the card restored; the player (not being Dummy) is, however, liable for all revokes which he may have meanwhile made.

The Revoke.

89. Is when a player (other than Dummy), holding one or more cards of the suit led, plays a card of a different suit.

90. The penalty for a revoke—

- I. Is at the option of the adversaries, who, at the end of the hand, may, after consultation, either take three tricks from the revoking player and add them to their own—or deduct the value of three tricks from his existing score—or add the value of three tricks to their own score;

- II. Can be claimed for as many revokes as occur during the hand;

- III. Is applicable only to the score of the game in which it occurs;

- IV. Cannot be divided—i.e. a player cannot add the value of one or two tricks to his own score and deduct the value of one or two from the revoking player.

- V. In whatever way the penalty may be enforced, under no circumstances can the suit revoking score Game, Grand Slam or Little Slam, that hand. Whatever their previous score may be, the side revoking cannot attain a higher score towards the game than twenty-eight.

91. A revoke is established, if the trick in which it occurs be turned and quitted—i.e. the hand removed from that trick after it has been turned face downwards on the table—or if either the revoking player or his partner, whether in his right turn or otherwise, lead or play to the following trick.

92. A player may ask his partner whether he has not a card of the suit which he has renounced; should the question be asked before the trick is turned and quitted, subsequent turning and quitting does not establish the revoke, and the error may be corrected, unless the question be answered in the negative, or unless the revoking player or his partner have led or played to the following trick.

- [Note.—A negative answer to the question does not in itself establish the revoke, apart from turning and quitting the trick, or some subsequent act of play.—Ed.]

93. At the end of the hand, the claimants of a revoke may search all the tricks.

94. If a player discover his mistake in time to save a revoke, any player or players who have played after him may withdraw their cards and substitute others, and their cards withdrawn are not liable to be called. If the player in fault be one of the dealer's adversaries, the dealer may call the card thus played in error, or may require him to play his highest or lowest card to that trick in which he has renounced.

95. If the player in fault be the dealer, the eldest hand may require him to play the highest or lowest card of the suit in which he has renounced, provided both of the dealer's adversaries have played to the current trick; but this penalty cannot be exacted from the dealer when he is fourth in hand, nor can it be enforced at all from Dummy.

96. If a revoke be claimed, and the accused player or his partner mix the cards before they have been sufficiently examined by the adversaries, the revoke is established. The mixing of the cards only renders the proof of a revoke difficult, but does not prevent the claim, and possible establishment, of the penalty.

97. A revoke cannot be claimed after the cards have been cut for the following deal.

98. If a revoke occur, be claimed and proved, bets on the odd trick, or on amount of score, must be decided by the actual state of the score after the penalty is paid.

99. Should the players on both sides subject themselves to the penalty of one or more revokes, neither can win the game by that hand; each is punished at the discretion of his adversary.

Calling for New Cards.

100. Any player (on paying for them) before, but not after, the pack be cut for the deal, may call for fresh cards. He must call for two new packs, of which the dealer takes his choice.

General Rules.

101. Any one during the play of a trick, or after the four cards are played, and before, but not after, they are touched for the purpose of gathering them together, may demand that the cards be placed before their respective players.

102. If either of the dealer's adversaries, prior to his partner playing, should call attention to the trick—either by saying that it is his, or by naming his card, or, without being required so to do, by drawing it towards him—the dealer may require that opponent's partner to play his highest or lowest of the suit then led, or to win or lose the trick.

103. Should the partner of the player solely entitled to exact a penalty, suggest or demand the enforcement of it, no penalty can be enforced.

104. In all cases where a penalty has been incurred, the offender is bound to give reasonable time for the decision of his adversaries.

105. If a bystander make any remark which calls the attention of a player or players to an oversight affecting the score, he is liable to be called on, by the players only, to pay the stakes and all bets on that game or rubber.

106. A bystander, by agreement among the players, may decide any question.

107. A card or cards torn or marked must be either replaced by agreement, or new cards called at the expense of the table.

108. Once a trick is complete, turned, and quitted, it must not be looked at (except under Law 88) until the end of the hand.

Books on Bridge.

The greater number of these have come into existence quite unnecessarily. All that the student need know will be found in the following:—

- Badsworth.—The Laws and Principles of Bridge, with Cases and Decisions reviewed and explained. (G. P. Putnam's Sons.)

- Bergholt, Ernest.—Double Dummy Bridge: [an exhaustive collection of card-problems by living composers]. (Thos. De la Rue & Co., Ld.)

- Dalton, William.—Bridge at a Glance: an Alphabetical Synopsis. (Thos. De la Rue & Co., Ld.)

- —— Bridge Abridged; or, Practical Bridge. (Do.)

- —— "Saturday" Bridge. (The West Strand Publishing Co., Ld.)

- Doe, John.—The Bridge Manual. (Frederick Warne and Co.)

- Hoffmann, Professor.—Bridge. (Chas. Goodall & Son, Ld.)

- For American Views on the Game.

- Elwell, J. B.—Bridge.—Advanced Bridge.—Practical Bridge. (Chas. Scribner's Sons, New York; and George Newnes, Ld., London.)

- Street, C. S.—Bridge Up to Date. Dodd, Mead & Co., New York.

- For Anglo-Indian Views.

- Hellespont.—The Laws and Principles of Bridge. (De la Rue, London)

- Ace of Spades.—The Theory and Practice of Bridge. (Times of India Press, Bombay.)

- Lynx.—Bridge Topics. (W. Newman & Co., Calcutta.)

- Robertson and Wollaston.—The Robertson Rule and other Bridge Axioms. (Calcutta.)