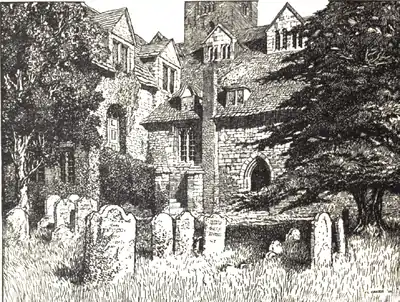

Pulborough Church

CHAPTER X

PETWORTH

Pulborough and its past—Stopham—Fittleworth—The natural advantages of the Swan—Petworth's feudal air—An historical digression naming many Percies—The third Earl of Egremont—The Petworth pictures—Petworth Park—Cobbett's opinion—The vicissitudes of the Petworth ravens—Tillington's use to business men—A charming epitaph—Noah Mann of the Hambledon Club.

Petworth is not on the direct road to Horsham, which is our next centre, but it is easily gained from Arundel by rail (changing at Pulborough), or by road through Bury, Fittleworth, and Egdean.

Pulborough is now nothing: once it was a Gibraltar, guarding Stane Street for Rome. The fort was on a mound west of the railway, corresponding with the church mound on the east. Here probably was a catapulta and certainly a vigilant garrison. Pulborough has no invader now but the floods, which every winter transform the green waste at her feet into a silver sea, of which Pulborough is the northern shore and Amberley the southern. The Dutch polder are not flatter or greener than are these intervening meadows. The village stands high and dry above the water level, extended in long line quite like a seaside town. Excursionists come too, as to a watering place, but they bring rods and creels and return at night with fish for the pan.

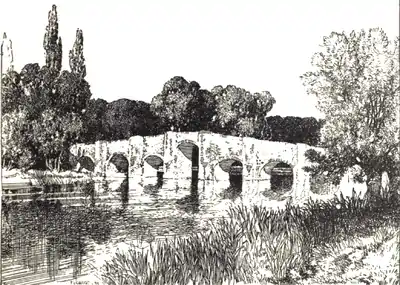

Between Pulborough and Petworth lie Stopham and Fittleworth, both on the Rother, which joins the Arun a little to the west of Pulborough. Stopham has the most beautiful bridge in Sussex, dating from the fourteenth century, and a little church filled with memorials of the Bartelott family. One of Stopham's rectors was Thomas Newcombe, a descendant of the author of The Faerie Queene, the friend of the author of Night Thoughts, and the author himself of a formidable poem in twelve books, after Milton, called The Last Judgment.

Fittleworth has of late become an artists' Mecca, partly because of its pretty woods and quaint architecture, and partly because of the warm welcome that is offered by the "Swan," which is probably the most ingeniously placed inn in the world. Approaching it from the north it seems to be the end of all things; the miles of road that one has travelled apparently have been leading nowhere but to the "Swan." Runaway horses or unsettled chauffeurs must project their passengers literally into the open door. Coming from the south, one finds that the road narrows by this inn almost to a lane, and the "Swan's" hospitable sign, barring the way, exerts such a spell that to enter is a far simpler matter than to pass.

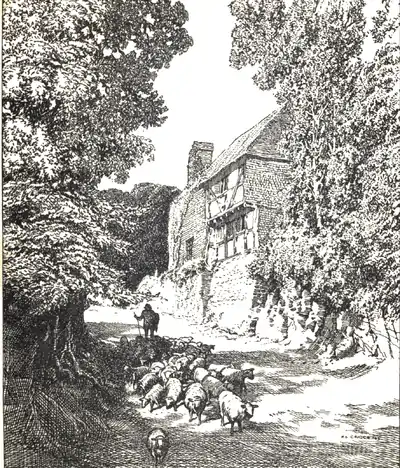

At Pulborough.

The "Swan" is a venerable and rambling building, stretching itself lazily with outspread arms; one of those inns (long may they be preserved from the rebuilders!) in which one stumbles up or down into every room, and where eggs and bacon have an appropriateness that make them a more desirable food than ambrosia. The little parlour is wainscoted with the votive paintings—a village Diploma Gallery—of artists who have made the "Swan" their home.

Fittleworth has a dual existence. In the south it is riparian and low, much given to anglers and visitors. In the north it is high and sandy, with clumps of firs, living its own life and spreading gorse-covered commons at the feet of the walker. Between its southern border and Bignor Park is a superb common of sand and heather, an inland paradise for children.

Petworth station and Petworth town are far from being the same thing, and there are few more fatiguing miles than that which separates them. A 'bus, it is true, plies between, but it is one of those long, close prisons with windows that annihilate thought by their shattering unfixedness. Petworth's spire is before one all the way, Petworth itself clustering on the side of the hill, a little town with several streets rather than a great village all on one artery. I say several streets, but this is dead in the face of tradition, which has a joke to the effect that a long timber waggon once entered Petworth's single, circular street, and has never yet succeeded in emerging. I certainly met it.

The town seems to be beneath the shadow of its lord even more than Arundel: it is like Pompeii, with Vesuvius emitting glory far above. One must, of course, live under the same conditions if one is to feel the authentic thrill; the mere sojourner cannot know it. One wonders, in these feudal towns, what it would be like to leave democratic London or the independence of one's country fastness, and pass for a while beneath the spell of a Duke of Norfolk, or a Baron Leconfield—a spell possibly not consciously cast by them at all, but existing none the less, largely through the fostering care of the townspeople on the rent-roll, largely through the officers controlling the estates; at any rate unmistakable, as present in the very air of the streets as is the presage of a thunderstorm. Surely, to be so dominated, without actual influence, must be very restful. Petworth must be the very home of low-pulsed peace; and yet a little oppressive too, with the great house and its traditions at the top of the town—like a weight on the forehead. I should not like to make Petworth my home, but as a place of pilgrimage, and a stronghold of architectural taste, it is almost unique.

Fittleworth Bridge[1]

In the Domesday Book Petworth is called Peteorde. It was rated at 1,080 acres, and possessed a church, a mill worth a sovereign, a river containing 1,620 eels, and pannage for 80 hogs. In the time of the Confessor the manor was worth £18; a few years later the price went down to ten shillings. Robert de Montgomerie held Petworth till 1102, when he defied the king and lost it. Adeliza, widow of Henry I., having a brother Josceline de Louvaine whom she wished to benefit, Petworth was given to him. Josceline married Agnes, daughter of William de Percy, the descendant of one of the Conqueror's chief friends, and, doing so, took his name. In course of time came Harry Hotspur, whose sword, which he swung at the Battle of Shrewsbury, is kept at Petworth House. The second Earl was his son, also Henry, who fought at Chevy Chase; he was not, however, slain there, as the balladmonger says, but at St. Albans. Henry, the third Earl, fell at Towton; Henry, the fourth Earl, was assassinated at Cock Lodge, Thirsk; Henry, the fifth Earl, led a regiment at the Battle of the Spurs; Henry, the sixth Earl, fell in love with Anne Boleyn, but had the good sense not to let Henry the Eighth see it. Thomas, his brother, was beheaded for treason; Thomas, the seventh Earl, took arms against Queen Elizabeth, and was beheaded in Scotland; Henry, the eighth Earl, attempted to liberate Mary Queen of Scots, and was imprisoned in the Tower, where he slew himself; Henry, the ninth Earl, was accused of assisting Guy Fawkes and locked up for fifteen years. He was set at liberty only after paying £30,000, and promising never to go more than thirty miles from Petworth House. This kept him out of London.

The last two noble Earls of Northumberland were Algernon, Lord High Admiral of England, who married Lady Anna Cecil, and planted an oak in the Park (it is still there) to commemorate the union; and Josceline, eleventh Earl, who died in 1670, leaving no son. He left, however, a daughter, a little Elizabeth, Baroness Percy, who had countless suitors and was married three times before she was sixteen. Her third husband was Charles Seymour, sixth Duke of Somerset, who became in time the father of thirteen children. Of these all died save three girls, and a boy, Algernon, who became seventh Duke of Somerset. Through one of the daughters, Catherine, who married Sir William Wyndham, the estates fell to the present family. The next important Lord of Petworth was George O'Brien Wyndham, third Earl of Egremont, the friend of art and agriculture, who collected most of the pictures. The present owner is the third Baron Leconfield.

The Rother at Fittleworth

C. R. Leslie, who painted more than one picture in the Petworth gallery, has much to say in his Autobiographical Recollections of its noble founder the third Earl, his generosity, courtesy, kindly thoughtfulness, and extreme modesty of bearing. One story contains half his biography. I give it in Leslie's words. After referring to his Lordship's men-servants and their importance in the house, the painter continues: "His own dress, in the morning, being very plain, he was sometimes by strangers mistaken for one of them. This happened with a maid of one of his lady guests, who had not been at Petworth before. She met him, crossing the hall, as the bell was ringing for the servants' dinner, and said: 'Come, old gentleman, you and I will go to dinner together, for I can't find my way in this great house.' He gave her his arm, and led her to the room where the other maids were assembled at their table, and said: 'You dine here, I don't dine till seven o'clock.'"

On certain days in the week visitors are allowed to walk through the galleries of Petworth House. The parties are shown by a venerable servitor into the audit room, a long bare apartment furnished with a statue and the heads of stags; and at the stroke of the hour a commissionaire appears at the far door and leads the way to the office, where a visitors' book is signed. Then the real work of the day begins, and for fifty-five minutes one passes from Dutch painters to Italian, from English to French: amid boors by Teniers, beauties by Lely, landscapes by Turner, carvings by Grinling Gibbons. The commissionaire knows them all. The collection is a fine one, but the lighting is bad, and the conditions under which it is seen are not favourable to the intimate appreciation of good art. One finds one's attention wandering too often from the soldier with his little index rattan to the deer on the vast lawn that extends from the windows to the lake—the lake that Turner painted and fished in. Hobbemas, Vandycks, Murillos—what are these when the sun shines and the ceaseless mutations of a herd of deer render the middle distance fascinating? Among the more famous pictures is a Peg Woffington by Hogarth, not here "dallying and dangerous," but demure as a nun; also the "Modern Midnight Conversation" from the same hand; three or four bewitching Romneys; a room full of beauties of the Court of Queen Anne; Henry VIII by Holbein; a wonderful Claude Lorraine; a head of Cervantes attributed to Velasquez; and four views of the Thames by Turner. Hazlitt, in his Sketches of the Picture Galleries of England, says of this collection:—"We wish our readers to go to Petworth … where they will find the coolest grottoes and the finest Vandykes in the world."

Lord Leconfield's park has not the remarkable natural formation of the Duke of Norfolk's, nor the superb situation of the Duke of Richmond and Gordon's, with its Channel prospects, but it is immense and imposing. Also it is unreal: it is like a park in a picture. This effect may be largely due to the circumstance that fêtes in Petworth Park have been more than once painted; but it is due also, I think, to the shape and colour of the house, to the lake, to the extent of the lawn, to the disposition of the knolls, and to the deer. A scene-painter, bidden to depict an English park, would produce (though he had never been out of the Strand) something very like Petworth. It is the normal park of the average imagination on a large scale.

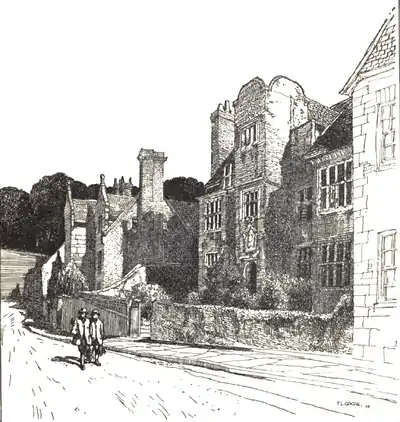

Almshouse at Petworth.

Cobbett wrote thus of Petworth:—"The park is very fine, and consists of a parcel of those hills and dells which nature formed here when she was in one of her most sportive moods. I have never seen the earth flung about in such a wild way as round about Hindhead and Blackdown, and this park forms a part of this ground. From an elevated part of it, and, indeed, from each of many parts of it, you see all around the country to the distance of many miles. From the south-east to the north-west the hills are so lofty and so near that they cut the view rather short; but for the rest of the circle you can see to a very great distance. It is, upon the whole, a most magnificent seat, and the Jews will not be able to get it from the present owner, though if he live many years they will give even him a twist."

On an eminence in the west is a tower (near a clump where ravens build), from which the other parks of this wonderful park-district of Sussex may be seen: Cowdray to the west, the highest points of Goodwood to the south-west, the highest points of Arundel to the south-east, and Parham's dark forest more easterly still. Mr. Knox's account of the vicissitudes of the Petworth ravens sixty years ago is as interesting as any history of equal length on the misfortunes of man. Their sufferings at the hands of keepers and schoolboys read like a page of Foxe. The final disaster was the spoliation of their nest by a boy, who removed all four of the children, or "squabs" as he called them. Mr. Knox, who used to come every day to examine them through his glass, was in despair, until after much meditation he thought of an expedient. Seeking out the boy he persuaded him to give up the one "squab" whose wings had not yet been clipped, and this the ornithologist carried to the clump and deposited in the ruined nest. The next morning the old birds were to be seen, just as of old, and that was their last molestation.

Just under the park on the road to Midhurst is Tillington, a little village with a rather ornamental church, which dates from 1807. There is nothing to say of Tillington, but I should like to quote a pretty sentence from Horsfield's History of Sussex concerning the monuments in the church, in a kind of writing of which we have little to-day:—"And as the volume, for which this has been written, is likely to fall chiefly into the hands of men who are occupied almost solely with the cares and business of this life, this slight reference is made to the monuments of the dead in order that, should the reader of this book find, in the present dearth of honesty, of faithfulness, of disinterested valour and of loyalty, an aching want in his spirit for such high qualities, let him hence be taught where to go—let him learn that, though they are rarely found in the busy haunts of men, they are still preserved and have their home around the sanctuary of the altar of his God."

Petworth should be visited by all young architects; not for the mansion (except as an object-lesson, for it is like a London terrace), but for the ordinary buildings in the town. It is a paradise of old-fashioned architecture. The church is hideous; the new hotel, the "Swan," might be at Balham; but the old part of the town is perfect. There is an almshouse (which Mr. Griggs has drawn), in which in its palmy days a Lady Bountiful might have lived; even the workhouse has charms—it is the only pretty workhouse I remember: with the exception, perhaps, of Battle, but that is, however, self-conscious.

Petworth has known, at any rate, one poet. In the churchyard was once this epitaph, now perhaps obliterated, from a husband's hand:—

"She was! She was! She was, what?

She was all that a woman should be, she was that."

In a book which takes account of Sussex men and women of the past, it is hard to keep long from cricket. To the north of Petworth, whither we now turn, is Northchapel, where was born and died one of the great men of the Hambledon Club, Noah Mann, who once made ten runs from one hit, and whose son was named Horace, after the cricketing baronet of the same name, by special permission. "Sir Horace, by this simple act of graceful humanity, hooked for life the heart of poor Noah Mann," says Nyren; "and in this world of hatred and contention, the love even of a dog is worth living for."

Petworth Churchyard.

This is Nyren's account of Noah Mann:

"He was from Sussex, and lived at Northchapel, not far from Petworth. He kept an inn there, and used to come a distance of at least twenty miles every Tuesday to practise. He was a fellow of extraordinary activity, and could perform clever feats of agility on horseback. For instance, when he has been seen in the distance coming up the ground, one or more of his companions would throw down handkerchiefs, and these he would collect, stooping from his horse while it was going at full speed. He was a fine batter, a fine field, and the swiftest runner I ever remember: indeed, such was his fame for speed, that whenever there was a match going forward, we were sure to hear of one being made for Mann to run against some noted competitor; and such would come from the whole country round. Upon these occasions he used to tell his friends, 'If, when we are half-way, you see me alongside of my man, you may always bet your money upon me, for I am sure to win.' And I never saw him beaten. He was a most valuable fellow in the field; for besides being very sure of the ball, his activity was so extraordinary that he would dart all over the ground like lightning. In those days of fast bowling, they would put a man behind the long-stop, that he might cover both long-stop and slip; the man always selected for this post was Noah. Now and then little George Lear (whom I have already described as being so fine a long-stop), would give Noah the wink to be on his guard, who would gather close behind him: then George would make a slip on purpose, and let the ball go by, when, in an instant, Noah would have it up, and into the wicket-keeper's hands, and the man was put out. This I have seen done many times, and this nothing but the most accomplished skill in fielding could have achieved....

"At a match of the Hambledon Club against All England, the club had to go in to get the runs, and there was a long number of them. It became quite apparent that the game would be closely fought. Mann kept on worrying old Nyren to let him go in, and although he became quite indignant at his constant refusal, our General knew what he was about in keeping him back. At length, when the last but one was out, he sent Mann in, and there were then ten runs to get. The sensation now all over the ground was greater than anything of the kind I ever witnessed before or since. All knew the state of the game, and many thousands were hanging upon this narrow point. There was Sir Horace Mann, walking about outside the ground, cutting down the daisies with his stick—a habit with him when he was agitated; the old farmers leaning forward upon their tall old staves, and the whole multitude perfectly still. After Noah had had one or two balls, Lumpy tossed one a little too far, when our fellow got in, and hit it out in his grand style. Six of the ten were gained. Never shall I forget the roar that followed this hit. Then there was a dead stand for some time, and no runs were made; ultimately, however, he gained them all, and won the game. After he was out, he upbraided Nyren for not putting him in earlier. 'If you had let me go in an hour ago' (said he), 'I would have served them in the same way.' But the old tactician was right, for he knew Noah to be a man of such nerve and self-possession, that the thought of so much depending upon him would not have the paralysing effect that it would upon many others. He was sure of him, and Noah afterwards felt the compliment. Mann was short in stature, and, when stripped, as swarthy as a gipsy. He was all muscle, with no incumbrance whatever of flesh; remarkably broad in the chest, with large hips and spider legs; he had not an ounce of flesh about him, but it was where it ought to be. He always played without his hat (the sun could not affect his complexion), and he took a liking to me as a boy, because I did the same."

Lurgashall, on the road to Northchapel, is a pleasant village, with a green, and a church unique among Sussex churches by virtue of a curious wooden gallery or cloister, said to have been built as a shelter for parishioners from a distance, who would eat their nuncheon there. The church, which has distinct Saxon remains, once had for rector the satirical James Bramston, author of "The Art of Politics" and "The Man of Taste," two admirable poems in the manner of Pope. This is his unimpeachable advice to public speakers:—

Those who would captivate the well-bred throng,

Should not too often speak, nor speak too long:

Church, nor Church Matters ever turn to Sport,

Nor make ''St. Stephen's Chappell, Dover-Court.