CHAPTER VII

THE chief reliance of St. John's was on their full-back, Hall Durham, who could outpunt by fifteen yards any one on the St. Timothy's team. The St. Timothy's ends and backs had been, therefore, specially prepared to meet a kicking game; theirs was the chief responsibility for making it ineffective.

Eastman, the quarter - back, and Frank Windsor had given a large part of each day's practice to catching punts. They were not likely to muff or fumble, but whether they would be able to run with the ball after catching it would depend entirely on the defensive work of the two ends. If this proved inferior, St. Timothy's chances would be slim; simply by kicking, St. John's could force her opponents back and back—and it was known that Durham was almost as good at kicking goals from the field as he was at punting.

As soon as they got the ball, St. John's started in to test the efficiency of their kicking game. Durham sent a splendid punt, high and far; but Holder and Herrick managed to delay the opposing ends just enough to give little Eastman a good start, and to enable him to dodge the first flying tackle.

He ran the ball back twenty yards, and there was great cheering from the St. Timothy's side, where the result of this first kick had been awaited with apprehension.

The two boys in the carriage behind the northern goal-posts watched the play with keen eyes, and commented on it from time to tune.

"That fellow who's in your place handles his man pretty cleverly," said the older boy.

"Oh, Joe Herrick! Yes, he's all right. It's the other end that I think may weaken. Holder's a green player, but he's doing well so far. How do you think they compare with your old eleven, Phil?"

Ward smiled. "After five years it's pretty hard to say. If you were in the game, Rupe, I might see somebody who was the equal of Clark Harding, but I don't just now."

Rupert laughed. "See anybody as good as Philip Ward?" he asked teasingly.

"Oh, about eleven. Fourth down! Neither side seems to gain much by rushing with the ball"

"Durham's going to kick again," Rupert predicted, and they both looked up the field in silent anxiety. The next moment there was a shout from St. John's, and Rupert uttered an exclamation of chagrin.

"Threw Windsor back a yard. Holder let his man through like a shot!" he muttered. "Now if we are n't able to gain, and have to kick"—

He said it all so moodily, resting his chin on his hand, that the older boy, glancing at him, smiled. A moment later, with St. Timothy's shouting, Rupert's face cleared. Windsor had made a twenty-yard rush through the centre.

"That puts us out of danger—temporarily," Rupert said. "But I'm afraid that Holder will make more such mistakes."

"Is he the best you've got? Who's his substitute?"

"Harry Harding."

"Oh! Clark's brother?"

"Yes."

"I remember seeing him once; but he used to be a light little thin kid."

"He's not very big now."

"Is he as good a fellow as Clark?"

"I don't know. I never knew Clark. But Harry's a mighty good fellow. If it's safe I'd like to put him in the last few minutes of the game. It would please him so much."

"He ought to be a good fellow," Ward said musingly. "Clark thinks everything of him, and from what I hear has done everything for him. I guess, Rupe, that if you were to put him in for a few minutes, being a Harding, he'd make good."

"He'll probably have a chance," Rupert answered.

Then, because St. Timothy's had the ball and seemed to be making, little by little, progress up the field, the talk between the two boys ceased, and they followed the game with a more intense interest. Up to the St. John's thirty-yard line—so far and no farther did St. Timothy's work their toilsome way. Then they lost the ball, and again Durham kicked.

The object of the St. John's strategy became more apparent to Rupert and Ward. Resting during the first half on a defensive game, they hoped to tire out their opponents. Then in the second half they would open up their hitherto unrevealed attack. And as the game went on, although the St. Timothy's goal was never seriously threatened, Rupert's face grew anxious. When the half ended, neither side had scored.

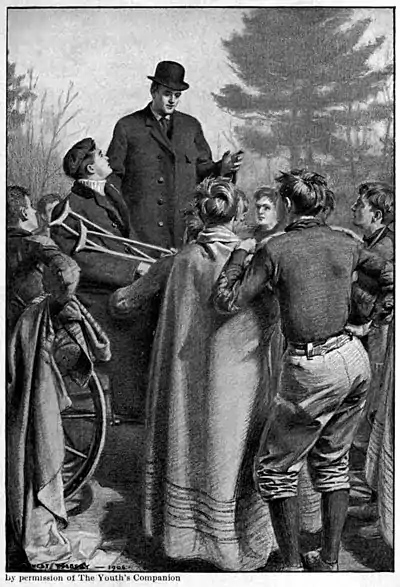

The St. John's eleven trotted off the field and entered the athletic house, which had been hospitably placed at their disposal. Instead of following them, the St. Timothy's players wrapped themselves in the blankets that the substitutes flung about them, and then, accompanied by the great mass of their supporters, went up to the carriage in which their captain sat. Then Frank Windsor turned and addressed the crowd.

"Move back, all you fellows!" he said. "Nobody but the eleven and the substitutes wanted here. Everybody else get back."

He waved his arms, and three or four other players stepped out and began waving their arms, until the crowd had retreated, abashed. Then the team gathered close about the carriage.

"You're doing well, fellows," Rupert said to them, his eyes shining with enthusiasm. "You're holding 'em mighty well—and you have n't shown up any of your trick plays yet. Tilden, your man was getting the jump on you there the last few minutes. You want to be a little quicker; but that was good, the way you broke through on that last kick. Holder, try to stiffen up your end a bit. Sometimes it was pretty ragged; but you're coming up to the scratch all right."

So he went down the list of players, criticising them when it was necessary, and then salving the criticism with some appreciative word, applauding enthusiastically without criticism when he could, and making each one in turn feel, through some quality in his voice and the look in his eyes, that the interest with which he had been watching the player was not merely that of a captain, but also that of a friend.

When he had finished his comments, he laid his hand on his companion's arm.

"Phil Ward here ought to be able to give you some points," he said to the team. "He played on St. Timothy's five years ago,—with Clark Harding and Skilton and those fellows,—and you all know he's had two years on a 'varsity team since. Phil, won't you talk to them?"

Ward laughed, and putting his hand on Rupert's shoulder, stood up. He was a tall, handsome, dark-faced fellow, with black eyebrows that met above his nose. His expression seemed determined, and might sometimes be severe, but now there was a pleasant twinkle in his eyes.

"I haven't much to say," he answered, "after hearing your captain talk. He seems to have covered the ground. I thought you fellows played mighty well that half. I don't

THERE WAS A PLEASANT TWINKLE IN HIS EYES

He patted Rupert's shoulder and smiled, and the eleven and the substitutes clapped in a way that showed they had taken his speech to heart. When he had sat down, Harry Harding, trailing his red blanket, came round behind the carriage and up to the side on which Ward was.

"How do you do, Mr. Ward?" he said shyly. "I guess you don't remember me. I'm Harry Harding."

"Of course I remember you!" cried Ward, reaching out his hand. "You've grown a good deal, but I'd know you anywhere for Clark's brother. What do you hear from him?"

"The last letter I had was written from Cairo a month ago," said Harry. "He and Archer Sands were going up the Nile."

"I've heard from him since then, I think. I'll see you later and give you his letter. I guess they're wanting you now."

The St. John's team was coming out of the athletic house. It was time to be returning to the field.

The second half revealed on both sides a less cautious and conservative style of play, and was, by contrast with what had gone before, sensational.

At the beginning, little Eastman caught the ball on the kick-off, and ran it sixty yards down the field, dodging and squirming out of the very arms of the St. John's tacklers; and St. Timothy's went delirious with joy.

Then the next moment the hero of this brilliant run, too excited perhaps by his achievement, fumbled the ball, and a St. John's player fell on it. St. John's lined up in a formation that bewildered St. Timothy's, quickly executed a trick, and sent their left half-back and left tackle skirting along one side of the field for a forty-yard run.

They lined up quickly and tried the trick again; but Herrick's mind had solved it, and he burst into the core of the formation and threw the runner back for a loss.

Then St. John's kicked, and St. Timothy's returned the kick; and back and forth in the middle of the field the two elevens struggled. The time slipped by. Rupert Ormsby kept glancing nervously at his watch.

"Well," he said, in a voice that was undecided between relief and disappointment, "they're holding 'em, anyway. And there can't be more than five minutes left."

St. John's tried a mass play against the St. Timothy's centre, and suddenly, while the two elevens were jammed together, the ball rolled jauntily, unconcernedly, out from the scrimmage.

Joe Herrick, pushing on the outside, saw it first, made a leap, and caught it up from the ground. The next moment, with it tucked under his left arm, he was racing up the field, up toward the carriage in which Ward and Rupert Ormsby sat.

The St. Timothy's spectators rushed yelling, along the side line. Ward stood up in the carriage, crying, "Come on! Come on!" Rupert hoisted a crutch, and shouted while he waved it.

But swift runner though Herrick was, the St. John's quarter-back was swifter, and heading diagonally up the field toward him, he gradually overhauled him, and at last, fifteen yards from the goal-line, hurled himself headlong through the air and dragged Herrick down.

It was the most daring and the prettiest tackle of the day; and at that the St. John's spectators swept up the field, swinging their caps and flags and cheering as defiantly as St. Timothy's were shouting joyously.

The St. John's captain rushed about among his men, slapping their backs, imploring them to stand firm. Frank Windsor was likewise going from one to another of his team, whispering what might be the magic word.

Then the teams lined up. Eastman, the quarter-back, had an inspiration.

"Fellows," he said, in a sharp voice, "Rupe's waiting for you just beyond the line."

Then he stopped and gave the signal. St. Timothy's charged forward and made a gain of three yards, and there was more wild shouting, and again Rupert was waving his crutch.

"You got near him that time!" cried Eastman, as the elevens lined up. "Mind, he's waiting for you!"

This time the attack was so desperate and concerted that it made ten yards, and the St. Timothy' s cheer did not cease even when the players got to their feet, but continued and continued, the leaders of it having worked themselves into a frenzy.

And now, with only two yards separating them from the goal-line, with Ward standing up in the carriage and shouting, and Rupert gesticulating wildly with arm and crutch, Eastman made himself heard:—

"You're going to shake hands with Rupe after this play!"

He shouted the signal that meant Perry at right tackle was to open up a hole.

And Perry responded to the call. He charged against his opponent furiously, and in the same instant Dennison, the fifth-form half-back, carrying the ball under his arm, came plunging through, and fell across the goal-line.

While the St. Timothy's spectators cheered and pranced and waved their flags, the players slowly got to their feet. The referee came up and looked at Dennison, who still lay, embracing the ball, a few inches across the line. The referee nodded, and then Dennison and the St. John's player, who had been hugging him desperately, rose.

The St. John's team walked disconsolately to the goal and ranged themselves under it, panting, with downcast heads. The St. Timothy's players were leaping and slapping one another and tumbling about on the field.

Rupert Ormsby lay back in the carriage with a serene smile of contentment. Then he thought of something, and sat up.

"Phil," he said to his companion, "don't you want to go down there and tell Harry Harding for me that he's to go on in Holder's place?"

Ward alighted from the carriage and ran to where Harry was standing with a group of the substitutes. He tapped him on the shoulder.

"Ormsby says you're to take Holder's place now," he said.

"Oh, he does!" Harry cried, in a voice quivering with excitement and delight. He tossed off his blanket, into the arms of two fellows who were already congratulating him. "Right now?"

"Yes," Ward answered, with a laugh. "And go in and play like Clark."

Dennison was holding the ball and Perry was getting ready to kick the goal when Harry ran out on the field. He said a word to Frank Windsor and turned to Holder, who shook hands with him cheerfully and then walked over to the line of applauding spectators. Their applause rose in another moment to a great height when Perry kicked the goal.

"And only one minute more to play!" Ward said to Rupert, as he climbed again into the carriage. "That's what one of the linesmen told me. Oh, we've got 'em licked!"

In the remaining minute St. John's secured possession of the ball just once, and tried a run round Harry's end. He hurled himself recklessly into the interference, and by a combination of luck and judgment got his arms round the half-back who was carrying the ball, and dragged him down before he had gained a yard.

A moment later, as the elevens were lining up, the timekeeper blew his whistle. Harry had the distinction of making the last tackle of the game.

After a cheer for their defeated opponents, who returned it bravely, the St. Timothy's eleven rushed up the field and gathered close beside Rupert's carriage. Behind them, shouting and tossing their flags, assembled the proud, victorious non-combatants. Frank Windsor stood up on the step of the carriage.

"Now then, fellows," he said, swinging one arm enthusiastically—and at that he lost his balance and slipped from the step to the ground, and the crowd laughed.

But the next moment he had climbed up again, as earnest as ever. "Now then, fellows, before you go in to dress, one cheer—three times three—for Captain Ormsby! One, two, three!"

Every St. Timothy's boy joined in that cheer. Rupert turned red and laughed, and then said something to Ward. And when the cheer was finished, Ward rose to his feet.

"Fellows," he said, "I say we cheer every man who played on the team to-day. First, left end"—He glanced down inquiringly at Rupert, who said, "Herrick."

"Three times three for Herrick!" cried Ward; and so he went down the list of players, and the St. Timothy's crowd stayed and helped him cheer them all, and last of all Harry Harding.

Then the gathering broke up. The members of the eleven ran to the athletic house; the other boys formed in column, arm in arm, and marched away toward the school, whistling the school song. And the St. John's boys who had come to see the game went straggling away very quietly.

"Well," said Phil Ward to Rupert, "you did it, and I congratulate you."

"Did nothing!" Rupert answered; and Ward suddenly recognized that the boy, in spite of all his happiness over the triumph of his eleven, was having at this moment his own private sorrow. So while they drove slowly away Ward sat in silence, allowing his companion to master this sudden bitterness. Then, as the carriage was turning into the road through the woods, the older boy said:—

"Would you mind stopping here and waiting for me a few moments, Rupert? I'd like to go into the athletic house and say a word to Clark's brother."

"All right," Rupert answered, in a voice that was quite cheerful. "Wish I could go with you. Stop here a few moments, please, Patrick."

Ward opened the door of the athletic house, and stood a moment, confused by changes in the place since the days when he had used it, yet pleasantly conscious that the spirit of it was the same.

The hot, damp reek of the great bathroom, from the open doors of which clouds of steam were issuing, the noisy, echoing voices of the boys, the heaps of dirty jerseys and moleskin trousers and heavy, cleated shoes lying about on the floor, the open lockers, in which clothing was crowded with varying regard for neatness, and, most of all, the boys themselves, loudly discussing, so earnest that they were forgetting to dress, forgetting, some of them, even to rub themselves dry with their towels,—these were the facts that somehow touched Phil Ward's heart and made him think of the time when he had been such a boy.

He looked about for Harry Harding, but saw no face that he recognized. In one corner a boy, stripped to the waist, lay flat on the floor, while another bent over him, kneading his back and rubbing it with alcohol. Ward stepped up and inspected the two; neither of them was Harry.

Over by the scales eight or ten naked fellows who had finished rubbing themselves down were waiting in line to see how much weight they had lost in the game. Harry was not among them; and indeed, as Ward looked about on the boys, deprived of their distinguishing colors, he could not tell who belonged to St. John's, who to St. Timothy's.

He stepped to the door of the great steaming bathroom, where members of both elevens were still fraternizing luxuriously under the showers, carrying on incoherent conversations in loud, echoing voices; and as he stood here, Harry came out, dripping, wringing the water from his hair.

"Hello!" said Ward, and Harry looked up at him from under his wet locks. "Congratulate you." He held out his hand.

"Thanks," said Harry. "My hand's all wet"—

"I don't mind a little thing like that. Now you'd better get to work and rub yourself down."

And while Harry, in accordance with this advice, seized a towel and began to polish himself to a bright pink, Ward stood by and made comments on the game. At last he said:

"Well, you're a credit to the family, Harry. You did all that Clark himself could have done. I guess I'll have to write to him about you. See you later; see you at the banquet to-night."

Then he went to rejoin Rupert, and he left Harry feeling very proud and happy.

Frank Windsor and Harry walked up together to their room. Frank was tired, and stretched himself out on the window-seat; but Harry had not played long enough for that and soon found he was restless. He went out to look for friends and talk with others about the great victory. Downstairs in the common room a group was gathered, and Bruce Watson, spying Harry, darted out from it, seized him, and dragged him forward. One after another they shook hands with him.

"That was a great tackle of yours, Harry." "Too bad you were n't in the game longer." "I bet you'd have done better than Holder." Such were the pleasant remarks that they showered upon him. And more than ever now he felt that he had won his spurs. He was an athlete really; and for the first time he felt with a serene satisfaction that his title to the office to which he had a month before been elected had been fairly earned.

Another honor was to be his that night. While the boys were talking, Mr. Eldredge, the master who had assisted in coaching the eleven and who always presided at the banquet which closed the football season, came up.

"Harding," he said, and he beckoned Harry to one side, "I want to give you warning. We expect to hear from you at the banquet to-night in answer to the toast, 'The Substitutes.'"

"Oh," said Harry, pleased and excited, "I'll see if I can think up something. But I have n't much time, have I, sir?"

"We shan't expect a great oratorical effort from you," Mr. Eldredge answered, with a smile, as he turned away.

But Harry, with his imagination already stirred by this new opportunity, thought it quite possible that he might surprise Mr. Eldredge.