CHAPTER X

IN silent fear Harry Harding and Joe Herrick looked at each other; then they turned and went silently down the infirmary steps. Typhoid fever! That would mean that Rupert would be out of everything for the rest of the year—out of athletics, out of the school life!

That it might perhaps mean even worse than this was a possibility which neither of the boys entertained. Rupert was so strong, so healthy, that indeed the most morbid imagination could hardly contemplate a fatal termination to his illness. But that he should be ill—and with such a tedious disease—was bad enough.

"Perhaps it's not typhoid fever," Harry said hopefully, as they walked away.

Herrick shook his head. "She would n't have suggested it might be unless she'd been pretty sure."

Harry acknowledged to himself that this was reasonable, and they walked on for a time in gloomy silence. Then Herrick suddenly broke out:—

"Oh, I feel as if it was all my fault! If I only had n't tripped him up that day, this might never have happened!"

"What nonsense!" Harry exclaimed. "What had that to do with his getting sick now?"

"You can't tell; it might have everything to do with it. I suppose maybe he got all run down being laid up so long without exercise. Oh, honestly, Harry, if I could, I 'd take his place now!"

"It will do him almost as much good to hear that you felt that way," said Harry. In the afternoon Harry went again to the infirmary, told the matron what Joe Herrick had wished, and asked her to repeat it to Rupert.

She promised to do this, but perhaps the message was never quite clearly understood in the boy's fever-burning brain. For typhoid fever it was indeed, and of a malignant violence.

"He must have been walking round with it for several days," Doctor Vincent said. And when the doctor was eagerly asked to express an opinion as to the probable duration of the illness, he shrugged his shoulders and answered, "That's something I can't predict."

No one besides the doctor and the nurses was admitted to see Rupert, and the reports from the sick-room did not, for a couple of weeks, vary much from day to day. During all this time his temperature remained high; he was generally in a comatose, or, at least, a torpid, state; he had periods of delirium.

When, day after day, the boys stopped at the infirmary and received only the report, "He's just about the same,"—never the encouraging word, "He's better this morning,"—they began to grow more grave and apprehensive. Just when or how the undercurrent of dread began, no one knew; but it was whispered about that Rupert was not improving, and that his mother was coming on from Chicago, and that a specialist from Boston had been sent for.

Harry went each morning into chapel with the fear that this day the rector would read the ominous prayer for the desperately sick. So long as that was omitted, he felt that Rupert's illness was not critical. Yet Doctor Vincent never spoke with any confidence about his patient; all he would say was that the disease had not yet reached its climax.

Francis Stoddard went about like one bereft; he seemed really to take no interest in his school life any more. He was listless in the class which he had once led; he went off in the afternoons alone on snow-shoes through the woods, repelling offers of companionship; he took part with only a perfunctory spirit in the exercises of the Pen and Ink, which had at first awakened his enthusiasm.

Harry noticed his apathy, and in unobtrusive ways tried to rouse him from it. He appealed to Francis for help in a dearth of manuscripts for the "Mirror;" he had Francis chosen as one of the debaters for the St. Timothy's medal in the great Pen and Ink debate of the year; and when there seemed danger of the boy's ignoring both these opportunities, Harry got him into a corner one day and talked to him.

"See here," he said, "do you think Rupert would stand for the way you're acting? Don't you realize that the one thing he'd want would be to have everything and everybody going on just the same as ever? Buck up now, and don't be any different from what you'd like to have him think you. And say, Francis, can't you really let me have a story for next month's 'Mirror'?"

Francis could not help smiling a little at this appeal. "I'll see what I can do," he promised, and then he added, "Thank you, Harry; I know you're right. But I've felt too blue to be of any use, that's all."

"Well, have n't I been feeling blue, too? Not that I'm of any particular use, either; but I guess I can be as blue as you are." He patted Francis on the shoulder; and three days later Francis brought him the manuscript, and told him that he had begun to work on the debate.

The days went by, and the question in the minds of the boys had ceased to be, Would Rupert be well enough to row or do anything in athletics toward the end of the year? Doctor Vincent had made it clear to them that of this there was no possibility. Even with the most rapid convalescence, it would be unsafe for Rupert to attempt any hard exercise for a long time to come.

When this was definitely settled, most of the boys in the school lost interest in his case. It was not because they were heartless, but it was as an athlete that Rupert was mainly known to them, and that they valued him. The dread which Harry and which Rupert's other close friends were beginning to feel and to try to put away from them had not yet occurred to most of the fellows, and they merely thought of Rupert as having a slow, stupid time, and hoped he would soon be sitting up, at least.

One morning after prayers, as the boys were passing out of the chapel, Harry saw a woman in black sitting beside the rector's wife. A certain familiar expression in her quite unfamiliar face caused him to glance at her a second time, and when he came down the chapel steps he said to Joe Herrick, who happened to be at his side:—

"Rupert's mother has come."

"How do you know?" asked Herrick.

"I saw her just now in the chapel. It must be his mother. She has the same way of looking at you from her eyes."

He told three or four other fellows in the sixth form; and before going to their rooms for the first hour of study, they loitered by the gate to see Mrs. Ormsby come out and make up their minds if it were really she. They had no doubt when she passed them, accompanied by Doctor Vincent, and turned with him toward the infirmary.

The boys had raised their caps as she went by, and she had swept them with a friendly, inquiring, almost wistful glance, as if she were wondering who among them were closest to her boy.

"She does n't look so awfully sad," said Harry.

"She looks pretty sad," declared Frank Windsor.

Three days later, when Harry and Frank Windsor were invited to tea at the rectory, to meet Mrs. Ormsby, they found her quite cheerful.

"The turning-point ought to come within a week, Doctor Vincent tells me," she said to them, when they asked her about Rupert. "And the doctor says Rupert is in as good condition to meet it as can be expected in so severe a case. If it comes to making a fight, I trust him."

"Yes," said Harry. "We can all do that."

At that moment he felt that Rupert could have no better ally to aid him in such a fight than his mother. She had the same brave heart as Rupert, she looked at one in the same brave, trusting way. With the sympathy that came from appreciation of his own mother, Harry felt that Mrs. Ormsby, by sitting at Rupert's bedside and holding his hand, could unite her spirit with his and bring him through triumphantly.

"He sleeps a great deal, and when he is n't asleep he's drowsy, and his mind seems never very clear," Mrs. Ormsby continued. "Sometimes he rambles on in talk about his friends and things he's been doing in the school. It's all disjointed, and I can't follow it.

"He's mentioned your names a good many times; and then there's a boy named Herrick and another named Stoddard that he talks about a good deal. This morning he was tremendously excited, addressing Herrick. It worried me, he was so excited. 'Herrick! Herrick!' he kept exclaiming, and then he quieted down, and said over and over again, in a consoling sort of way, 'It's all right, Herrick. Never mind what the school thinks; it's all right, Herrick.' And when he'd said that three or four times, he began to say, 'Thank you, Herrick, for wanting to take my place, but I've got to play this half through myself, I've got to play this half through myself.' He dropped off to sleep still murmuring it."

Harry winked sudden tears from his eyes; Rupert had received his message.

"That will please Herrick," he said. "I'll tell him."

"I wish I could remember all he's said about you, Harry. They were very nice things." Mrs. Onnsby smiled. "He seemed so afraid you would n't understand why he was refusing to do something—to join some society, I think. He was afraid he'd hurt your feelings."

"He never did that. I—I guess I know what he meant."

Afterward, when they went away, Harry said to Frank Windsor, "That was the Crown Rupert was talking about." Frank nodded and made no answer.

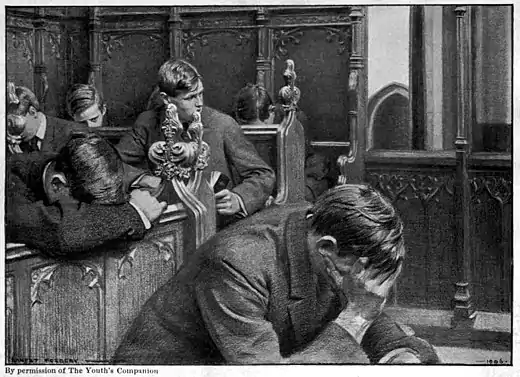

It was three mornings after this, on Saturday, that Harry, trying to solve a neglected geometry problem in the few minutes between breakfast and chapel, found himself with too little time to stop at the infirmary for news of the patient. Indeed, he had to go by the building at a run. He entered the chapel just as the doors were closing, and settled into his seat, breathless.

He was dreaming through the usual prayers when suddenly his senses started awake with a throb. The rector, in his deep voice and with an even deeper solemnity than that which had accompanied the preceding words, had begun the prayer—"O Lord, look down from heaven, behold, visit and relieve thy sick servant."

Harry, with his heart beating fast in sudden fright, raised his eyes, and from where he knelt looked out into the antechapel. The rector's wife was there, with her head bowed; but the chair beside her, in which Mrs. Ormsby had been accustomed to sit, was vacant.

From the chancel the rector's voice, more solemn, more impressive, was proceeding; and Harry, conscious now of the meaning, closed his eyes again and echoed, with a fervent and imploring soul, that prayer—echoed it up to its submissive alternative—"or else, give him grace so to take thy visitation, that, after this painful life ended, he may dwell with thee in life everlasting." Against those words Harry closed his lips.

On their way from chapel to the classroom the boys of the sixth form commented in subdued tones upon the rector's prayer. Harry demanded anxiously of one and then of another if there was any news. At last Joe Herrick edged through the crowd toward him.

"I stopped," Herrick said. "It's the crisis. Of course they've been expecting it. They can't tell how soon the turn may come, one way or the other. He may be like this for forty-eight hours."

"Like what?" Harry demanded.

"Fighting for life."

Harry put his hand out upon the banister rail and gripped it while he toiled up the stairs. The strength seemed to have gone from his knees; he had no heart for lessons or for play. Then he recalled the brave faith of Rupert's mother,—"If it should come to a fight,"—and he kept saying to himself

HARRY, WITH HIS HEART BEATING FAST ... LOOKED OUT INTO THE ANTECHAPEL

Mr. Eldredge, usually so even-tempered, had a harassed look in the class that morning, and was severe with the boys who were slow or unprepared.

He sent Harry to the blackboard to demonstrate a theorem. Harry made his drawings languidly, and Mr. Eldredge looked on at him with an exasperation which the rest of the class noted. The work was done correctly enough, however; and when he had finished drawing the figure, Harry reached for a pointer with which to make his demonstration. In doing this he knocked down an eraser from its shelf. It fell clattering to the floor, and Mr. Eldredge, who had for a moment looked away, jumped.

"That will do for you, Harding!" he said. "Take your seat."

Harry turned submissively. The master saw there were tears in his eyes. He called on Francis Stoddard to finish the demonstration. At the end of the hour he asked Harry to stay behind, and when the boy came up to his desk, he said:—

"Harry, I'm afraid my nerves are not very good this morning; you can guess why. I need n't have sent you to your seat."

"It's all right, sir," Harry answered. "Mr. Eldredge,"—he looked up at him appealingly,—"have you heard anything, sir? Do you think he'll pull through?"

"I've only heard that it's very critical." The master gathered up his papers and books and walked away with Harry, talking to him about Rupert and recalling little acts of the boy which Harry had never known. "He's made the school better for being in it," said the master, as they parted.

Harry sat during the next study hour on the window-seat of his room, with a Greek book open before him, but he looked out of the window more than at the text. He looked across at the gabled end of the infirmary, where he knew that Rupert lay. The things that Rupert had done, and those which Rupert had tried and had failed to do—he measured beside them his own efforts and achievements.

What was most worthy in these had received impetus and help from Rupert; all that was mistaken had met Rupert's opposition. And now, as Harry's thoughts swept back over the year, he felt humbly how small and young a figure he had presented, how kind and generous to him Rupert had always been. At the thought of Rupert wasted away to a shadow, delirious in a darkened room, gasping for breath—Harry threw his Iliad on the table and buried his face in his arms.

That afternoon the Pythiansand Corinthians played the deciding game for the hockey championship; and in the heat of contest no doubt the sick boy was forgotten. Pythian and Corinthian clashed sticks and sped after the puck with the ardent zeal to win; but when the game was finished, and the championship rested with the Corinthians, they made little parade of their triumph.

Instead, Tilden, their captain, skated up to Bruce Watson, who was leading the Pythians, and after shaking his hand, said, "If you'd had Rupert, it would have been different;" and then together they skated to the bank and asked one of the bystanders if there was any news.

Harry saw only part of the game. He left it twice to walk up to the infirmary, in hope of being the first to receive an encouraging bulletin.

But it was always the same—"Condition unchanged." It was the last word that he heard from Mr. Eldredge when he went to bed that night; it was the response to his inquiry the next morning.

That afternoon, at the regular meeting of the Crown, which was held in Herrick's room instead of at the sacred rock, owing to a heavy fall of snow, Harry put forth his ultimatum. It was not conceived on the spur of the moment. It was the outgrowth of his reflections of the past few days.

"Fellows," he said, "some of you won't agree with me, but I hope, anyway, you'll listen. You all remember how Rupert Ormsby once refused to join our society—and how some of us accused him of all sorts of motives. I happened to hear the other day—from his mother—that in his delirium he'd been trying to explain why he felt obliged to refuse—trying to put it so it would n't hurt my feelings. We all know now there was just one reason why he refused—and that was because he thought a secret society like the Crown was a poor thing in such a school as this.

"Now I want to say to you fellows that in my heart I believe Rupert was right! I could n't help believing it at the time, but I would n't own up to it. A secret society like this is apt to give its members a false idea of their importance, and make them jealous of the success of anybody outside. And it is a cliquey, undemocratic kind of thing, no matter how well it's run. Some day, if it's kept alive, a discontented crowd will organize an opposition society, and that will mean a continuous split in the school.

"Now I propose that we disband—and not only that, but that we go to the fifth-formers that are expecting to be elected into the Crown and tell them why we've discontinued it, and ask them for the good of the school not to reorganize it.

"I wish you'd all talk it over now; and I hope you'll come to my opinion. I'd like to say one more thing,—not as a threat, or anything of that sort, you understand, but just because I have come to feel so out of sympathy,—and that is, that if you decide to continue the Crown, I want to resign, not only as president, but as a member."

Herrick spoke up immediately in support of Harry's suggestion. Albree opposed it, and Bruce Watson deprecated it.

The others seemed disturbed in mind and unwilling to express an opinion. But at last Frank Windsor came out openly in favor of disbanding. He acknowledged he had been reluctant to take that view, but he believed there was truth in what his roommate said, and he had decided to back him up.

And that was the beginning of the end. Gradually the others were brought round, and at last the Crown adjourned forever.

"It will please Rupert when he's well enough to hear it," Frank Windsor said to Harry afterward.

"If only he will some time be well enough!" Harry answered.

The next morning it seemed that Harry's wish might soon be granted. The welcome news ran through the school at breakfast that Rupert had passed the crisis, that the upward turn had begun. The prayer for the desperately sick was not said that morning in chapel. A new spirit of happiness seemed to have awakened and to pervade all the school exercises. It shone in the faces of masters and of boys.

Harry and Francis Stoddard went snow-shoeing together in the afternoon, and found no words to confide to each other their joy. Frank Windsor and Joe Herrick, among the candidates for the crew exercising in the gymnasium, forgot in their pleasant thoughts the strain that was being put upon their muscles.

But after a couple of days the report from the infirmary was less favorable. Rupert did not improve as had been expected. There was still cause for alarm.

Within two weeks the relapse came suddenly. The school heard of it at noon. That evening, after supper, the rector entered the great schoolroom, where all the boys except the privileged sixth-formers sat studying.

They looked up with surprise and apprehension as the rector slowly paced up the aisle to the platform, looking neither to the right nor to the left. The master in charge of the schoolroom rose from his chair. The rector mounted the steps to the platform and stood beside him. And all the boys looked up in a breathless hush.

"Boys," said the rector, in a quivering voice, unlike that which they were accustomed to hear, "one of your best-beloved comrades is lying to-night at the point of death. I need not ask you when you leave this room to go to your dormitories as quietly, as noiselessly, as you can."

That evening Harry Harding, as he sat in his room, heard the bell from the chapel tower proclaim the end of study. He put aside his books, and waited to hear the familiar sound of voices and laughter, and of feet tramping up from the study building along the board walk. He waited, but he heard nothing.

At last, in wonder, he went to the window. It was a moonlight night. The board walk that led past the infirmary down to the study stretched shining and empty; but on each side of it were boys, singly and in groups, but all silent, trudging ankle-deep through the snow.