CHAPTER V

"TO GET YOUR OWN LIVING"

"No," said Mr. Beale, "we ain't agoin' to crack no more cribs. It's low—that's what it is. I quite grant you it's low. So I s'pose we'll 'ave to take the road again."

Dickie and he were sitting in the sunshine on a sloping field. They had been sitting there all the morning, and Dickie had told Mr. Beale all his earthly adventures from the moment the red-headed man had lifted him up to the window of Talbot Court to the time when he had come in by the open door of the common lodging-house.

"What a nipper it is, though!" said Mr. Beale regretfully. "For the burgling, I mean—sharp—clever—no one to touch him. But I don't cotton to it myself," he added quickly, "not the burgling, I don't. You're always liable to get yourself into trouble over it, one way or the other—that's the worst of it. I don't know how it is," he ended pensively, "but somehow it always leads to trouble."

Dickie picked up seven straws from among the stubble and idly plaited them together; the nurse had taught him this in the dream when he was still weak from the fever.

"That's very flash, that what you're doing," said Beale; "who learned you that?"

"I learned it in a dream," said Dickie slowly. "I dreamed I 'ad a fever—and—I'll tell you if you like: it's a good yarn—good as Here Ward, very near."

Beale lay back on the dry stubble, his pipe between his teeth.

"Fire away," he said, and Dickie fired away.

When the long tale ended, the sun was beginning to go down towards its bed in the west. There was a pause.

"You'd make a tidy bit on the 'alls," said Beale, quite awestruck. "The things you think of! When did you make all that up?"

"I dreamed it, I tell you," said Dickie.

"You always could stick it on," said Mr. Beale admiringly.

"I ain't goin' to stick it on never no more," said Dickie. "They called it lying and cheating, where I was—in my dream, I mean."

"Once let a nipper out of yer sight," said Mr. Beale sadly, "and see what comes of it! 'No. 2' a-goin' to stick it on no more! Then how's us to get a honest living? Answer me that, young chap."

"I don't know," said Dickie, "but we got to do it som'ow."

"It ain't to be done—not with all the unemployed there is about," said Mr. Beale. "Besides, you've got a regular gift for sticking it on—a talent I call it. And now you want to throw it away. But you can't. We got to live."

"In the dream," said Dickie, "there didn't seem to be no unemployed. Every one was 'prenticed to a trade. I wish it was like that here."

"Well, it ain't," said Mr. Beale shortly. "I wasn't never 'prenticed to no trade, no more'n what you'll be."

"Worse luck," said Dickie. "But I started learning a lot of things—games mostly, in the dream, I did—and I started making a boat—a galleon they called it. All the names is different there. And I carved a little box—a fair treat it was—with my father's arms on it."

"Yer father's what?"

"Coat of arms. Gentlemen there all has different things—patterns like; they calls 'em coats of arms, and they put it on their silver and on their carriages and their furniture."

"Put what?" Beale asked again.

"The blazon. All gentlepeople have it."

"Don't you come the blazing toff over me," said Beale with sudden fierceness, "cause I won't 'ave it. See? It's them bloomin' Talbots put all this rot into your head."

"The Talbots? " said Dickie. "Oh! the Talbots ain't been gentry more than a couple of hundred years. Our family's as old as King Alfred."

"Stow it, I say!" said Beale, more fiercely still. "I see what you're after; you want us to part company, that's what you want. Well, go. Go back to yer old Talbots and be the nice lady's little boy with velvet kicksies and a clean anky once a week. That's what you do."

Dickie looked forlornly out over the river.

"I can't 'elp what I dreams, can I?" he said. "In the dream I'd got lots of things. Uncles and aunts an' a little brother. I never seen him though. An a farver and muvver an' all. It's different 'ere. I ain't got nobody but you 'ere—farver."

"Well, then," said Beale more gently, "what do you go settin of yourself up agin me for?"

"I ain't," said Dickie. "I thought you liked me to tell you everythink."

Silence. Dickie could not help noticing the dirty shirt, the dirty face, the three days' beard, the filthy clothes of his friend, and he thought of his other friend, Sebastian of the Docks. He saw the pale blue reproachful eyes of Beale looking out of that dirty face, and he spoke aloud, quite without meaning to.

"All that don't make no difference," he said.

"Eh?" said Beale with miserable, angry eyes.

"Look 'ere," said Dickie desperately. "I'm a-goin' to show you. This 'ere's my Tinkler, what I told you about, what pawns for a bob. I wouldn't show it to no one but you, swelp me, I wouldn't."

He held the rattle out.

Beale took it. "It's a fancy bit, I will say," he owned.

"Look 'ere," said Dickie, "what I mean to say"

He stopped. What was the use of telling Beale that he had come back out of the dream just for his sake? Beale who did not believe in the dream—did not understand it—hated it?

"Don't you go turning agin me," he said; "whether I dream or not, you and me'll stand together. I'm not goin' to do things wot's wrong—low, dirty tricks—so I ain't. But I knows we can get on without that. What would you like to do for your living if you could choose?"

"I warn't never put to no trade," said Beale, "'cept being 'andy with a 'orse. I was a wagoner's mate when I was a boy. I likes a 'orse. Or a dawg," he added. "I ain't no good wiv me 'ands—not at working, you know—not to say working."

Dickie suppressed a wild notion he had had of getting into that dream again, learning some useful trade there, waking up and teaching it to Mr. Beale.

"Ain't there nothing else you'd like to do?" he asked.

"I don't know as there is," said Mr. Beale drearily; "without it was pigeons."

Then Dickie wondered whether things that you learned in dreams would "stay learnt." Things you learned to do with your hands. The Greek and the Latin "stayed learned" right enough and sang in his brain encouragingly.

"Don't you get shirty if I talks about that dream," he said. "You dunno what a dream it was. I wasn't kidding you. I did dream it, honour bright. I dreamed I could carve wood—make boxes and things. I wish I 'ad a bit of fine-grained wood. I'd like to try. I've got the knife they give me to cut the string of the basket in the train. It's jolly sharp."

"What sort o' wood?" Beale asked.

"It was mahogany I dreamed I made my box with," said Dickie. "I would like to try."

"Off 'is poor chump," Beale murmured with bitter self-reproach; "my doin' too—puttin' 'im on to a job like Talbot Court, the nipper is."

He stretched himself and got up.

"I'll get yer a bit of mahogany from somewheres," he said very gently. "I didn't mean nothing, old chap. You keep all on about yer dreams. I don't mind. I likes it. Let's get a brace o' kippers and make a night of it."

So they went back to the Gravesend lodging-house.

Next day Mr. Beale produced the lonely leg of a sofa—mahogany, a fat round turned leg, old and seasoned.

"This what you want?" he asked.

Dickie took it eagerly. "I do wonder if I can," he said. "I feel just exactly like as if I could. I say, farver, let's get out in the woods somewheres quiet and take our grub along. Somewheres where nobody can't say, 'What you up to?' and make a mock of me."

They found a place such as Dickie desired, a warm, sunny nest in the heart of a green wood, and all through the long, warm hours of the autumn day Mr. Beale lay lazy in the sunshine while Dickie, very pale and determined, sliced, chipped, and picked at the sofa leg with the knife the gardener had given him.

It was hard to make him lay the work down even for dinner, which was of a delicious and extravagant kind—new bread, German sausage, and beer in a flat bottle. For from the moment when the knife touched the wood Dickie knew that he had not forgotten, and that what he had done in the Deptford dockyard under the eyes of Sebastian, the shipwright who had helped to sink the Armada, he could do now alone in the woods beyond Gravesend.

It was after dinner that Mr. Beale began to be interested.

"Swelp me!" he said; "but you've got the hang of it somehow. A box, ain't it?"

"A box," said Dickie, smoothing a rough corner; "a box with a lid that fits. And I'll carve our arms on the top—see, I've left that bit stickin' up a purpose."

It was the hardest day's work Dickie had ever done. He stuck to it and stuck to it and stuck to it till there was hardly light left to see it by. But before the light was wholly gone the box had wholly come with the carved coat-of-arms and the lid that fitted.

"Well," said Mr. Beale, striking a match to look at it; "if that ain't a fair treat! There's many a swell bloke 'ud give 'arf a dollar for that to put 'is baccy in. You've got a trade, my son, that's sure. Why didn't you let on before as you could? Blow the beastly match! It's burnt me finger."

The match went out and Beale and Dickie went back to supper in the crowded, gas-lit room. When supper was over—it was tripe and onions and fried potatoes, very luxurious—Beale got up and stood before the fire.

"I'm a goin' to 'ave a hauction, I am," he said to the company at large. "Here's a thing and a very pretty thing, a baccy-box, or a snuff-box, or a box to shut yer gold money in, or yer diamonds. What offers?"

"'And it round," said a black-browed woman, with a basket covered in American cloth no blacker than her eyes.

"That I will," said Beale readily. "I'll 'and it round in me 'and. And I'll do the 'andin' meself."

He took it round from one to another, showed the neat corners, the neat carving, the neat fit of the square lid.

"Where'd yer nick that?" asked a man with a red handkerchief.

"The nipper made it."

"Pinched it more likely," some one said.

"I see 'im make it," said Beale, frowning a little.

"Let me 'ave a squint," said a dingy grey old man sitting apart. For some reason of his own Beale let the old man take the box into his hand. But he kept very close to him and he kept his eyes on the box.

"All outer one piece," said the old man. "I dunno oo made it an' I don't care, but that was made by a workman as know'd his trade. I was a cabinetmaker once, though you wouldn't think it to look at me. There ain't nobody here to pay what that little hobjec's worth. Hoil it up with a drop of cold linseed and leave it all night, and then in the morning you rub it on yer trowser leg to shine it, and then rub it in the mud to dirty it, and then hoil it again and dirty it again, and you'll get 'arf a thick un for it as a genuwine hold antique. That's wot you do."

"Thankee, daddy," said Beale, "an' so I will."

He slipped the box in his pocket. When Dickie next saw the box it looked as old as any box need look.

"Now we'll look out for a shop where they sells these 'ere hold antics," said Beale. They were on the road and their faces were set towards London. Dickie's face looked pinched and white. Beale noticed it.

"You don't look up to much," he said; "warn't your bed to your liking?"

"The bed was all right," said Dickie, thinking of the bed in the dream. "I diden sleep much, though."

"Any more dreams?" Beale asked kindly enough.

"No," said Dickie. "I think p'raps it was me wanting so to dream it again kep' me awake."

"I dessey," said Beale, picking up a straw to chew.

Dickie limped along in the dust, the world seemed very big and hard. It was a long way to London and he had not been able to dream that dream again. Perhaps he would never be able to dream it. He stumbled on a big stone and would have fallen but that Beale caught him by the arm, and as he swung round by that arm Beale saw that the boy's eyes were thick with tears.

"Ain't 'urt yerself , 'ave yer?" he said—for in all their wanderings these were the first tears Dickie had shed.

"No," said Dickie, and hid his face against Beale's coat sleeve. "It's only"

"What is it, then?" said Beale, in the accents of long-disused tenderness; "tell your old farver, then"

"It's silly," sobbed Dickie.

"Never you mind whether it's silly or not," said Beale. "You out with it."

"In that dream," said Dickie, "I wasn't lame."

"Think of that now," said Beale admiringly. "You best dream that every night. Then you won't mind so much of a daytime."

"But I mind more," said Dickie, sniffing hard; "much, much more."

Beale, without more words, made room for him in the crowded perambulator, and they went on. Dickie's sniffs subsided. Silence. Presently—

"I say, farver, I'm sorry I acted so silly. You never see me blub afore and you won't again," he said; and Beale said awkwardly, "That's all right, mate."

"You pretty flush?" the boy asked later on.

"Not so dusty," said the man.

"'Cause I wanter give that there little box to a chap I know wot lent me the money for the train to come to you at Gravesend."

"Pay 'im some other day when we're flusher."

"I'd rather pay 'im now," said Dickie. "I could make another box. There's a bit of the sofer leg left, ain't there?"

There was, and Dickie worked away at it in the odd moments that cluster round meal times, the half-hours before bed and before the morning start. Mr. Beale begged of all likely foot-passengers, but he noted that the "nipper" no longer "stuck it on." For the most part he was quite silent. Only when Beale appealed to him he would say, "Farver's very good to me. I don't know what I should do without farver."

And so at last they came to New Cross again, and Mr. Beale stepped in for half a pint at the Railway Hotel, while Dickie went clickety-clack along the pavement to his friend the pawnbroker.

"Here we are again," said that tradesman; "come to pawn the rattle?"

Dickie laughed. Pawning the rattle seemed suddenly to have become a very old and good joke between them.

"Look 'ere, mister," he said; "that chink wot you lent me to get to Gravesend with." He paused, and added in his other voice, "It was very good of you, sir."

"I'm not going to lend you any more, if that's what you're after," said the Jew, who had already reproached himself for his confiding generosity.

"It's not that I'm after," said Dickie, with dignity. "I wish to repay you."

"Got the money?" said the Jew, laughing not unkindly.

"No," said Dickie; "but I've got this." He handed the little box across the counter.

"Where'd you get it?"

"I made it."

The pawnbroker laughed again. "Well, well, I'll ask no questions and you'll tell me no lies, eh?"

"I shall certainly tell you no lies," said Dickie, with the dignity of the dream boy who was not a cripple and was heir to a great and gentle name; "will you take it instead of the money?"

The pawnbroker turned the box over in his hands, while kindness and honesty struggled fiercely within him against the habits of a business life. Dickie eyed the china vases and concertinas and teaspoons tied together in fan shape, and waited silently.

"It's worth more than what I lent you," the man said at last with an effort; "and it isn't every one who would own that, mind you."

"I know it isn't, said Dickie; "will you please take it to pay my debt to you, and if it is worth more, accept it as a grateful gift from one who is still gratefully your debtor."

"You'd make your fortune on the halls," said the man, as Beale had said; "the way you talk beats everything. All serene. I'll take the box in full discharge of your debt. But you might as well tell me where you got it."

"I made it," said Dickie, and put his lips together very tightly.

"You did—did you? Then I'll tell you what. I'll give you four bob for every one of them you make and bring to me. You might do different coats of arms see?"

"I was only taught to do one," said Dickie.

Just then a customer came in—a woman with her Sunday dress and a pair of sheets to pawn because her man was out of work and the children were hungry.

"Run along, now," said the Jew, "I've nothing more for you to-day." Dickie flushed and went.

Three days later the crutch clattered in at the pawnbroker's door, and Dickie laid two more little boxes on the counter.

"Here you are," he said. The pawnbroker looked and exclaimed and questioned and wondered, and Dickie went away with eight silver shillings in his pocket, the first coins he had ever carried in his life. They seemed to have been coined in some fairy mint; they were so different from any other money he had ever handled.

Mr. Beale, waiting for him by New Cross Station, put his empty pipe in his pocket and strolled down to meet him. Dickie drew him down a side street and held out the silver. "Two days' work," he said. "We ain't no call to take the road 'cept for a pleasure trip. I got a trade, I 'ave. 'Ow much a week's four bob a day? Twenty-four bob I make it."

"Lor!" said Mr. Beale, with his mouth open.

"Now I tell you what, you get 'old of some more old sofy legs and a stone and a strap to sharpen my knife with. And there we are. Twenty-four shillings a week for a chap an' 'is nipper ain't so dusty, farver, is it? I've thought it all up and settled it all out. So long as the weather holds we'll sleep in the bed with the green curtains, and I'll 'ave a green wood for my workshop, and when the nights get cold we'll rent a room of our very own and live like toffs, won't us?"

The child's eyes were shining with excitement.

"'Pon my sam, I believe you like work," said Mr. Beale in tones of intense astonishment.

"I like it better'n cadgin'," said Dickie.

They did as Dickie had said, and for two days Mr. Beale was content to eat and doze and wake and watch Dickie's busy fingers and eat and doze again. But on the third day he announced that he was getting the fidgets in his legs.

"I must do a prowl," he said; "I'll be back afore sundown. Don't you forget to eat your dinner when the sun comes level the top of that high tree. So long, matey."

Mr. Beale slouched off in the sunshine in his filthy old clothes, and Dickie was left to work alone in the green and golden wood. It was very still. Dickie hardly moved at all, and the chips that fell from his work fell more softly than the twigs and acorns that dropped now and then from some high bough. A goldfinch swung on a swaying hazel branch and looked at him with bright eyes, unafraid; a grass snake slid swiftly by—it was out on particular business of its own, so it was not afraid of Dickie nor he of it. A wood-pigeon swept rustling wings across the glade where he sat, and once a squirrel ran right along a bough to look down at him and chatter, thickening its tail as a cat does hers when she is angry.

It was a long and very beautiful day, the first that Dickie had ever spent alone. He worked harder than ever, and when by the lessening light it was impossible to work any longer, he lay back against a tree root to rest his tired back and to gloat over the thought that he had made two boxes in one day—eight shillings—in one single day, eight splendid shillings.

The sun was quite down before Mr. Beale returned. He looked unnaturally fat, and as he sat down on the moss something inside the front of his jacket moved and whined.

"Oh! what is it?" Dickie asked, sitting up, alert in a moment; "not a dawg? Oh! farver, you don't know how I've always wanted a dawg."

"Well, you've a-got yer want now, three times over, you 'ave," said Beale, and, unbuttoning his jacket, took out a double handful of soft, fluffy sprawling arms and legs and heads and tails—three little fat, white puppies.

"Oh, the jolly little beasts!" said Dickie; "ain't they fine? Where did you get them?"

"They was give me," said Mr. Beale, re-knotting his handkerchief, "by a lady in the country."

He fixed his eyes on the soft blue of the darkening sky.

"Try another," said Dickie calmly.

"Ah! it ain't no use trying to deceive the nipper—that sharp he is," said Beale, with a mixture of pride and confusion. "Well, then, not to deceive you, mate, I bought 'em."

"What with?" said Dickie, lightning quick.

"With—with money, mate—with money, of course."

"How'd you get it?"

No answer.

"You didn't pinch it?"

"No—on my sacred sam, I didn't," said Beale eagerly; "pinching leads to trouble. I've 'ad my lesson."

"You cadged it, then?" said Dickie.

"Well," said Beale sheepishly, "what if I did?"

"You've spoiled everything," said Dickie, furious, and he flung the two newly finished boxes violently to the ground, and sat frowning with eyes downcast.

Beale, on all fours, retrieved the boxes.

"Two," he said, in awestruck tones; "there never was such a nipper!"

"It doesn't matter," said Dickie in a heart-broken voice, "you've spoiled everything, and you lie to me, too. It's all spoilt. I wish I'd never come back outer the dream, so I do."

"Now lookee here," said Beale sternly, "don't you come this over us, 'cause I won't stand it, d'y 'ear? Am I the master or is it you? D'ye think I'm going to put up with being bullied and druv by a little nipper like as I could lay out with one 'and as easy as what I could one of them pups?" He moved his foot among the soft, strong little things that were uttering baby-growls and biting at his broken boot with their little white teeth.

"Do," said Dickie bitterly, "lay me out if you want to. I don't care."

"Now, now, matey"—Beale's tone changed suddenly to affectionate remonstrance—"I was only kiddin'. Don't take it like that. You know I wouldn't 'urt a 'air of yer 'ed, so I wouldn't."

"I wanted us to live honest by our work—we was doing it. And you've lowered us to the cadgin' again. That's what I can't stick," said Dickie.

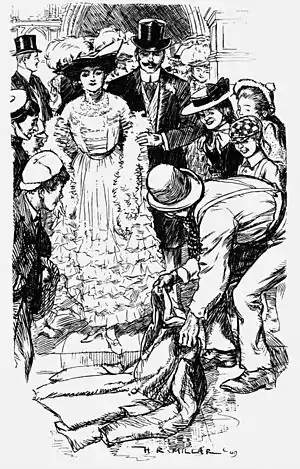

"It wasn't. I didn't have to do a single bit of patter for it anyhow. It was a wedding, and I stopped to 'ave a squint, and there'd been a water-cart as' ad stopped to 'ave a squint too, and made a puddle as big as a tea-tray, and all the path wet. An' the lady in her white, she looks at the path and the gent 'e looks at 'er white boots—an' I offs with me coat like that there Rally gent you yarned me about, and flops it down in the middle of the puddle, right in front of the gal.

"'AN' I OFF'S WITH ME COAT, AND FLOPS IT DOWN IN THE MIDDLE OF THE PUDDLE, RIGHT IN FRONT OF THE GAL.'"

[Page 120.

"Yes," said Dickie, "go on."

"And she just touched me 'and and walks across me coat. And the people laughed and clapped—silly apes! And the gent 'e tipped me a thick un, and I spotted the pups a month ago, and I knew I could have 'em for five bob, so I got 'em. And I'll sell 'em for thrible the money, you see if I don't. An' I thought you'd be as pleased as pleased—me actin' so silly, like as if I was one of them yarns o' yourn an' all. And then first minute I gets 'ere, you sets on to me. But that's always the way."

"Please, please forgive me, father," said Dickie, very much ashamed of himself; "I am so sorry. And it was nice of you and I am pleased—and I do love the pups—and we won't sell all three, will us? I would so like to have one. I'd call it 'True.' One of the dogs in my dream was called that. You do forgive me, don't you, father?"

"Oh! that's all right," said Beale.

Next day again a little boy worked alone in a wood, and yet not alone, for a small pup sprawled and yapped and scrapped and grunted round him as he worked. No squirrels or birds came that day to lighten Dickie's solitude, but True was more to him than many birds or squirrels. A woman they had overtaken on the road had given him a bit of blue ribbon for the puppy's neck, in return for the lift which Mr. Beale had given her basket on the perambulator. She was selling ribbons and cottons and needles from door to door, and made a poor thing of it, she told them. "An' my grandfather 'e farmed 'is own land in Sussex," she told them, looking with bleared eyes across the fields.

Dickie only made a box and a part of a box that day. And while he sat making it, far away in London a respectable-looking man was walking up and down Regent Street among the shoppers and the motors and carriages, with a fluffy little white dog under each arm. And he sold both the dogs.

"One was a lady in a carriage," he told Dickie later on. "Arst 'er two thick uns, I did. Never turned a hair, no more I didn't. She didn't care what its price was, bless you. Said it was a dinky darling and she wanted it. Gent said he'd get her plenty better. No—she wanted that. An' she got it too. A fool and his money's soon parted's what I say. And t'other one I let 'im go cheap, for fourteen bob, to a black clergyman—black as your hat he was, from foreign parts. So now we're bloomin' toffs, an' I'll get a pair of reach-me-downs this very bloomin' night. And what price that there room you was talkin' about?"

It was the beginning of a new life. Dickie wrote out their accounts on a large flagstone near the horse trough by the "Chequers," with a bit of billiard chalk that a man gave him.

It was like this:—

Got Box 4

Box 4

Box 4

Box 4

Dog 40

Dog 14

——

70

Spent Dogs 4

Grub 19

Tram 4

Leg 2

——

29

and he made out before he rubbed the chalk off the stone that the difference between twenty-nine shillings and seventy was about two pounds—and that was more than Dickie had ever had, or Beale either, for many a

long year.

Then Beale came, wiping his mouth, and they walked idly up the road. Lodgings. Or rather a lodging. A room. But when you have had what is called the key of the street for years enough, you hardly know where to look for the key of a room.

"Where'd you like to be?" Beale asked anxiously. "You like country best, don't yer?"

"Yes," said Dickie.

"But in the winter-time?" Beale urged.

"Well, town then," said Dickie, who was trying to invent a box of a new and different shape to be carved next day.

"I could keep a look-out for likely pups," said Beale; "there's a plenty here and there all about—and you with your boxes. We might go to three bob a week for the room."

"I'd like a 'ouse with a garden," said Dickie.

"Go back to yer Talbots," said Beale.

"No—but look 'ere," said Dickie, "if we was to take a 'ouse—just a little 'ouse, and let half of it."

"We ain't got no sticks to put in it."

"Ain't there some way you get furniture without payin' for it?"

"'Ire systim. But that's for toffs on three quid a week, reg'lar wages. They wouldn't look at us."

"We'll get three quid right enough afore we done," said Dickie firmly; "and if you want London, I'd like our old house because of the seeds I sowed in the garden; I lay they'll keep on a coming up, for ever and ever. That's what annuals means. The chap next door told me. It means flowers as comes up fresh every year. Let's tramp up, and I'll show it to you—where we used to live."

And when they had tramped up and Dickie had shown Mr. Beale the sad-faced little house, Mr. Beale owned that it would do 'em a fair treat.

"But we must 'ave some bits of sticks or else nobody won't let us have no 'ouses."

They flattened their noses against the front window. The newspapers and dirty sackings still lay scattered on the floor as they had fallen from Dickie when he had got up in the morning after the night when he had had The Dream.

The sight pulled at Dickie's heart strings. He felt as a man might feel who beheld once more the seaport from which in old and beautiful days he had set sail for the shores of romance, the golden splendour of The Fortunate Islands.

"I could doss 'ere again," he said wistfully; "it 'ud save fourpence. Both 'ouses both sides is empty. Nobody wouldn't know."

"We don't need to look to our fourpences so sharp's all that," said Beale.

"I'd like to."

"Wonder you ain't afeared."

"I'm used to it," said Dickie; "it was our own 'ouse, you see."

"You come along to yer supper," said Beale; "don't be so flash with yer own 'ouses."

They had supper at a coffee-shop in the Broadway.

"Two mugs, four billiard balls, and 'arf a dozen doorsteps," was Mr. Beale's order. You or I, more polite if less picturesque, would perhaps have said, "Two cups of tea, four eggs, and some thick bread and butter." It was a pleasant meal. Only just at the end it turned into something quite different. The shop was one of those old-fashioned ones, divided by partitions like the stalls in a stable, and over the top of this partition there suddenly appeared a head.

Dickie's mug paused in air half-way to his mouth, which remained open.

"What's up?" Beale asked, trying to turn on the narrow seat and look up, which he couldn't do.

"It's 'im," whispered Dickie, setting down the mug. "That red-'eaded chap wot I never see."

And then the red-headed man came round the partition and sat down beside Beale and talked to him, and Dickie wished he wouldn't. He heard little of the conversation; only "better luck next time" from the red-headed man, and "I don't know as I'm taking any" from Beale, and at the parting the red-headed man saying, "I'll doss same shop as wot you do," and Beale giving the name of the lodging-house where, on the way to the coffee-shop, Beale had left the perambulator and engaged their beds.

"Tell you all about it in the morning" were the last words of the red-headed one as he slouched out, and Dickie and Beale were left to finish the doorsteps and drink the cold tea that had slopped into their saucers.

When they went out Dickie said—

"What did he want, farver—that red-headed chap?"

Beale did not at once answer.

"I wouldn't if I was you," said Dickie, looking straight in front of him as they walked.

"Wouldn't what?"

"Whatever he wants to."

"Why, I ain't told you yet what he does want."

"'E ain't up to no good—I know that."

"'E's full of notions, that's wot 'e is," said Beale. "If some of 'is notions come out right 'e'll be a-ridin' in 'is own cart and 'orse afore we know where we are and us a-tramping in 'is dust."

"Ridin' in Black Maria, more like," said Dickie.

"Well, I ain't askin' you to do anything, am I?" said Beale.

"No!—you ain't. But whatever you're in, I'm a-goin' to be in, that's all."

"Don't you take on," said Beale comfortably; "I ain't said I'll be in anything yet, 'ave I? Let's 'ear what 'e says in the morning. If 'is lay ain't a safe lay old Beale won't be in it—you may lay to that."

"Don't let's," said Dickie earnestly. "Look 'ere, father, let us go, both two of us, and sleep in that there old 'ouse of ours. I don't want that red-'eaded chap. He'll spoil everything—I know 'e will, just as we're a-gettin' along so straight and gay. Don't let's go to that there doss; let's lay in the old 'ouse."

"Ain't I never to 'ave never a word with nobody without it's you?" said Beale, but not angrily.

"Not with 'im; 'e ain't no class," said Dickie firmly; "and oh! farver, I do so wanter sleep in that 'ouse, that was where I 'ad The Dream, you know."

"Oh, well—come on, then," said Beale; "lucky we've got our thick coats on."

It was quite easy for Dickie to get into the house, just as he had done before, and to go along the passage and open the front door for Mr. Beale, who walked in as bold as brass. They made themselves comfortable with the sacking and old papers—but one at least of the two missed the luxury of clean air and soft moss and a bed canopy strewn with stars. Mr. Beale was soon asleep and Dickie lay still, his heart beating to the tune of the hope that now at last, in this place where it had once come, his dream would come again. But it did not come—even sleep, plain, restful, dreamless sleep, would not come to him. At last he could lie still no longer. He slipped from under the paper, whose rustling did not disturb Mr. Beale's slumbers, and moved into the square of light thrown through the window by the street lamp. He felt in his pockets, pulled out Tinkler and the white seal, set them on the floor, and, moved by memories of the great night when his dream had come to him, arranged the moon-seeds round them in the same pattern that they had lain in on that night of nights. And the moment that he had lain the last seed, completing the crossed triangles, the magic began again. All was as it had been before. The tired eyes that must close, the feeling that through his closed eyelids he could yet see something moving in the centre of the star that the two triangles made.

"Where do you want to go to?" said the same soft small voice that had spoken before. But this time Dickie did not reply that he was "not particular." Instead, he said, "Oh, there! I want to go there!" feeling quite sure that whoever owned that voice would know as well as he, or even better, where "there" was, and how to get to it.

And as on that other night everything grew very quiet, and sleep wrapped Dickie round like a soft garment. When he awoke he lay in the big four-post bed with the green and white curtains; about him were the tapestry walls and the heavy furniture of The Dream.

"Oh!" he cried aloud, "I've found it again!—I've found it!—I've found it!"

And then the old nurse with the hooped petticoats and the queer cap and the white ruff was bending over him; her wrinkled face was alight with love and tenderness.

"So thou'rt awake at last," she said. "Did'st thou find thy friend in thy dreams?"

Dickie hugged her.

"I've found the way back," he said; "I don't know which is the dream and which is real—but you know."

"Yes," said the old nurse, "I know. The one is as real as the other."

He sprang out of bed and went leaping round the room, jumping on to chairs and off them, running and dancing.

"What ails the child?" the nurse grumbled; "get thy hose on, for shame, taking a chill as like as not. What ails thee to act so?"

"It's the not being lame," Dickie explained, coming to a standstill by the window that looked out on the good green garden. "You don't know how wonderful it seems, just at first, you know, not to be lame."