Ulinish and Talisker (September 21-25).

On the morning of Tuesday, September 21, our travellers took advantage of a break in the stormy weather to continue their journey to Ulinish, a farm-house on Loch Bracadale, occupied by

| An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

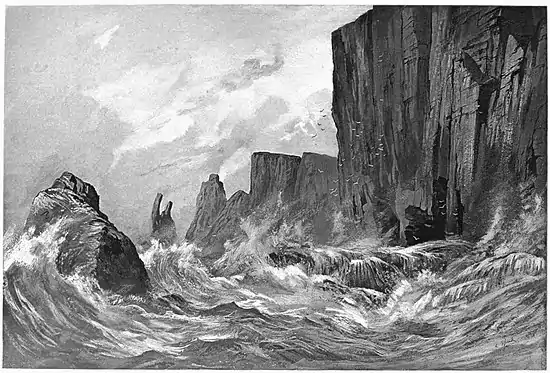

TALISKER HEAD AND ORONSAY.

"a plain honest gentleman," the Sheriff-substitute of the island. Here they passed the night, and here, if we may trust report, Johnson's powers as a drinker of tea were exerted to their utmost pitch. "Mrs. Macleod of Ulinish," writes Knox, "has not forgotten the quantity of tea which she filled out to Dr. Johnson, amounting to twenty-two dishes."[1] Surely for this outrageous statement some of those excuses are needed " by which," according to Boswell, "the exaggeration of Highland narratives is palliated." From an old tower near the house a fine view was had of the Cuillin, or Cuchullin Hills, "a prodigious range of mountains, capped with rocky pinnacles in a strange variety of shapes," which with good reason reminded Boswell of the mountains he had seen near Corte in Corsica.

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE & RIVINGTON, LTD, PUBLISHERS, LONDON

IMP & HELIOC LEMERCIER & CIE, PARIS

On the afternoon of the following clay "an interval of calm sunshine," writes Johnson, "courted us out to see a cave on the shore famous for its echo. When we went into the boat one of our companions was asked in Erse by the boatmen who they were that came with him. He gave us characters, I suppose, to our advantage, and was asked in the spirit of the Highlands whether I could recite a long series of ancestors. The boatmen said, as I perceived afterwards, that they heard the cry of an English ghost. This, Boswell says, disturbed him. We came to the cave, and clambering up the rocks came to an arch open at one end, one hundred and eighty feet long, thirty broad in the broadest part, and about thirty feet high. There was no echo; such is the fidelity of reports; but I saw what I had never seen before, mussels and whelks in their natural state. There was another arch in the rock open at both ends." This cave was not on the shore of Skye, as Johnson's account seems to imply, but in the little island of Wia. From Boswell we learn that it was to an island they were taken. We were fortunate enough on our visit to this wild part of the coast to have as our guide one of Macleod's gamekeepers. "A man," to borrow from Johnson the praise which he bestowed on one of his guides, 'of great liveliness and activity, civil and ready-handed."[2] We had passed the night in the lonely little inn at Struan on the shore of an arm of Loch Bracadale, where we had found decent, if homely, lodging. In a fisherman's boat we rowed down the loch, sometimes in mid-channel and sometimes skirting the cliffs, which rose like a wall of rock to a great height above us. We passed little islets, and the mouths of caverns which filled with clouds of spray as the long rolling waves swept in from the Atlantic. On the ledges of the rocks, hovering over our heads, swimming and diving in the sea, were cormorants, puffins, oyster catchers, gulls, curlews and guillemots. We had none of us looked upon a wilder scene. When we reached our island we were pleased to find that the narrow beach at which we were to land was guarded by a huge headland from the swell of the sea. Whether we visited the cave which our travellers saw I do not feel at all sure, for it does not correspond with their description. My friend, the gamekeeper, was sure that it was the place, and I was willing to advance my faith more than half-way to meet his assertion. We scrambled up the steep beach, and then over rocks covered with grass and ferns, between the sides of a narrow gorge. At the top a still steeper path led downwards to a cave, at the bottom of which we could see a glimmer of light. Scrambling upwards again, we reached a place where we could hear the sea murmuring on the other side. We afterwards climbed to the top of the cliff and sat down on the ground which formed the roof of the cavern. It was covered with heather and ferns, and patches of short grass; a pleasant breeze was blowing, the sea birds were uttering their cries, far beneath us we could hear the beating of the surge. Across the Loch on both sides, the dark cliffs rose to a great height, and in the background stood the mountains of Skye and of the mainland. Had the air been very clear, we might have seen on the north-west the wooded hills of Dunvegan.

Two or three days later, when I was giving two Highlanders an account of this cavern, one of them asked with a humorous smile: "Did they not tell you it was Prince Charlie's Cave? He must, I am thinking, have been sleeping everywhere." His companion laughed and said: "They have lately made a new one near an hotel which they have opened at———." The innkeepers should surely show a little originality. Why should they not advertise Dr, Johnson's Cave, and show the tea-pot out of which he drank his two-and-twenty cups of tea when he picnicked there? They would do well also to discover the great cave in Skye which Martin tells of. "It is supposed," he writes, "to exceed a mile in length. The natives told me that a piper who was over-curious went in with a design to find out the length of it, and after he entered began to play on his pipe, but never returned to give an account of his progress."[3]

From Ulinish our travellers sailed up Loch Bracadale on their way to Talisker. "We had," says Boswell, "good weather and a fine sail. The shore was varied with hills, and rocks, and cornfields, and bushes, which are here dignified with the name of natural wood." They landed at Ferneley, a farm-house about three miles from Talisker, whither they made their way over the hills, Johnson on horseback, the rest on foot. The weather, no doubt, had been too uncertain for them to venture into the open sea round the great headland at the entrance of the loch. Skirting the stern and rock-bound coast, a few miles' sail would have brought

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE & RIVINGTON, LTD, PUBLISHERS, LONDON

IMP & HELIOC LEMERCIER & CIE, PARIS

them to Talisker Hay, within sight of Colonel Macleod's house. Yet, had the wind risen, or had there been a swell from the Atlantic, they would have been forced to keep out to sea. Boswell describes " the prodigious force and noise with which the billows break on the shore." "It is," says Johnson, "a coast where no vessel lands but when it is driven by a tempest on the rocks." Only two nights before his arrival two boats had been wrecked there in a storm. "The crews crept to Talisker almost lifeless with wet, cold, fatigue, and terror."

| An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

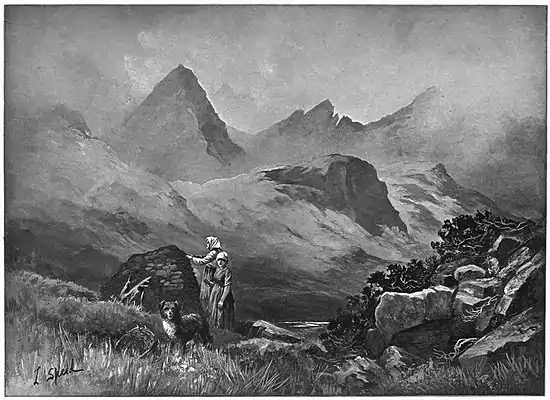

LANDING PLACE.

What could not be safely done near the end of September, might, we thought, be hazarded in June. As the day was fine and we had a good sea-boat, an old fisherman to manage it, our trusty gamekeeper to help in rowing, and an accomplished yachtsman in our artist, we boldly sailed forth into the Atlantic. We passed in sight of Macleod's Maidens, beneath rocks such as Mr. Brett and Mr. Graham delight to paint. In one spot we were shown where, a few years before, a huge mass had come tumbling down. At the entrance to the Bay we passed through a narrow channel in the rocks with the waves foaming on each side. Even our stout-hearted gamekeeper for a moment looked uneasy, but with a few strong strokes of the oars the worst was past, and we were out of the broken waters, and in full sight of the little bay with its beach of great black stones, its rugged and steep headlands, and its needle rocks, with one of the sunniest of valleys for its background. Johnson thought it "the place, beyond all he had seen, from which the gay and the jovial seem utterly excluded; and where the hermit might grow old in meditation without possibility of disturbance or interruption."

| An image should appear at this position in the text. If you are able to provide it, see Wikisource:Image guidelines and Help:Adding images for guidance. |

VIEWS AT TALISKER.

To us on that fine June day, with the haze lying on the hills, it was as if

One sight, to which I had long looked forward, I missed. It was no longer "a land of streams." There was no spot where

Boswell had counted "fifteen different waterfalls near the house in the space of about a quarter of a mile." "They succeeded one another so fast," said Johnson, "that as one ceased to be heard another began." This one thing was wanting on that beautiful afternoon which we spent in this delightful spot. The voice of the cascades was still. There were no waterfalls streaming down the lofty hills. One indeed we found by following the course of a river up a fine glen, but owing to the long drought its roar had sunk into a murmur.

Johnson's host, Colonel Macleod, was the good kinsman who had befriended the young Laird in the troubles which he encountered on his succession to the property.

"He had," writes Boswell, "been bred to physic, had a tincture of scholarship in his conversation, which pleased Dr. Johnson, and he had some very good books; and being a colonel in the Dutch service, he and his lady, in consequence of having lived abroad, had introduced the ease and politeness of the continent into this rude region."

Pennant, writing in the year 1774, thus describes these Scotch regiments in the Dutch service:

"They were formed out of some independent companies sent over either in the reign of Elizabeth or James VI. At present the common men are but nominally national, for since the scarcity of men occasioned by the late war, Holland is no longer permitted to draw her recruits out of North Britain. But the officers are all Scotch, who are obliged to take oaths to our government, and to qualify in presence of our ambassador at the Hague."[4]

In the war which broke out between England and Holland in 1781, this curious system, which had survived the great naval battles between the two countries in the seventeenth century, at last came to an end. In the Gentlemen's Magazine for December, 1782, we read, that on the first of that month:

"The Scotch Brigade in the Dutch service renounced their allegiance to their lawful Sovereign, and took a new oath of fidelity to their High Mightinesses. They are for the future to wear the Dutch uniform, and not to carry the arms of the enemy any longer in their colours, nor to beat their march. They are to receive the word of command in Dutch, and their officers are to wear orange-coloured sashes, and the same sort of spontoons as the officers of other Dutch regiments."[5]

Colonel Macleod, if he was still living, lost, of course, his command. At the time of our travellers' visit he was on leave of absence, which had been extended for some years, says Johnson, "in this time of universal peace." The knowledge which he had gained in Holland he turned to good account in Skye. He both drained the land which lay at the foot of the mountains round Talisker, and made a good garden. 'He had been," says Knox, "an observer of Dutch improvements. He carried off in proper channels the waters of two rivers which often deluged the bottom. He divided the whole valley by deep and sometimes wide ditches into a number of square fields and meadows. He now enjoys the fruits of his ingenuity in the quantity of grain and hay raised thereon." He had made it "the seat of plenty, hospitality, and good nature."[6] To few places in our islands could Dutch art have been transplanted where it would find nature more kindly. Johnson noticed the prosperous growth of the trees, which, though they were not many years old, were already very high and thick. Could he have seen them at the present clay he would have owned that even in the garden of an Oxford College there are few finer. The soil is so good, we were told, "that things have only to be planted and they grow." So sheltered from all the cold winds is the position, and so great is the warmth diffused by the beneficent Gulf Stream, that the whole year round flowers live out of doors which anywhere but on the southern coasts of Devonshire and Cornwall would be killed by the frosts. The garden is delightfully old-fashioned, entirely free from the dismal formality of ribbon-borders. Fruit trees, flowers, shrubs, and vegetables mingle together. It lies open to the south-west, being enclosed on the other sides with groves of trees. A lawn shaded by a noble sycamore stretches up to the house. Boswell would have been pleased to find that smooth turf now covers the court which in his time was "most injudiciously paved with round blueish-grey pebbles, upon which you walked as if upon cannon-balls driven into the ground." The house "in its snug corner " has been greatly enlarged, but the old building still remains. Unfortunately no tradition has been preserved of the room occupied by Johnson. Much as he admired this sequestered spot "a place where the imagination is more amused cannot easily be found," he said nevertheless it was here that he quoted to Boswell the lines of the song:

"Every island is a prison

Strongly guarded by the sea;

Kings and princes, for that reason,

Prisoners are as well as we."

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON, SEARLE & RIVINGTON, LTD, PUBLISHERS, LONDON

IMP & HELIOC LEMERCIER & CIE, PARIS

Island, Bernera, the Loch of Dunvegan, part of Rum, part of Raasay, and a vast deal of the Isle of Skye." According to Pennant, who had made the ascent the year before:

"It has in front a fine series of genuine basaltic columns, resembling the Giant's Causeway. The ruins of the columns at the base made a grand appearance; they were the ruins of the creation. This is the most northern basalt I am acquainted with; the last of four, all running from south to north—the Giant's Causeway, Staffa, the rock Humbla, and Briis-mhawl. The depth of ocean in all probability conceals the lost links of this chain."[7]

This mountain, which he calls Briis-mhawl, in Boswell's narrative appears as Prieshwell.

At Talisker Johnson made the acquaintance of young Macleane of Col, that amiable man whose death by drowning the following year he so much lamented. Under his guidance, taking leave of their kind hosts, they rode across the island to Sconser, on the coast opposite to Raasay. Of this part of their journey they tell us next to nothing, though they passed through the wildest scenery. For the first two or three miles their path wound up a valley that is not unworthy of the most delightful parts of Cumberland. It is altogether free from the utter desolation which casts a gloom over so much of Skye. The sloping sides of the hills are covered with short grass and fragrant herbs. All about in summer time are dotted the sheep and lambs, answering each other with their bleats. When we travelled along this way we passed a band of five-and-twenty shearers who had been hard at work for many days. The farm of Talisker keeps a winter stock of between five and six thousand Cheviot sheep, and the clipping takes a long time. Dropping into the valley on the other side of the hills the road leads beyond the head of Loch Harport across the island to Sligachan, where amidst gloomy waste now stands a comfortable hotel. In the little garden which surrounds it is the only trace of cultivation to be anywhere seen. It would have seemed impossible to add anything to the dreariness of the scenery; nevertheless something has been added by the long line of gaunt telegraph posts which stretches across the moor. Perhaps at this spot stood the little hut where our travellers made a short halt, as they watched an old woman grinding at the quern. With one hand she rapidly turned round the uppermost of two mill-stones, while with the other she poured in the corn through a hole pierced through it. A ride of a few more miles brought the party, through the gloom of evening, to Sconser, where they dined at the little inn.

- ↑ Knox's Tour, p. 139.

- ↑ For his services and for many other acts of kindness, I am indebted to the Rev. Roderick Macleod of Macleod.

- ↑ M. Martin's Western Islands, p. 150.

- ↑ Pennant's Voyage to the Hebrides, ed. 1774, p. 289.

- ↑ Gentleman's Magazine, 1782, p. 595.

- ↑ Knox's Tour, p. 140.

- ↑ Voyage to the Hebrides, ed. 1774, p. 291.