MONTANA, one of the north-western Territories of the United States, is limited on the N. by British Columbia, on the E. by Dakota, on the S. by Wyoming and Idaho, and on the W. by Idaho. Its boundaries, as established by statute, are as follows:—on the N., the 49th parallel; on the E., the 27th meridian west of Washington, or the 104th west of Greenwich; on the S. and W. the boundary follows the 45th parallel from the 27th meridian west to the 34th meridian west, then turns south along the latter meridian to its point of intersection with the continental watershed, thence along the crest-line of this watershed westward and north-westward until it reaches the Bitter-root Mountains; it then follows the crest of this range north-westward to the point where it is crossed by the 39th meridian west, which it follows north to the line of British Columbia. The total area is about 146,080 square miles—an approximate estimate, as the boundary along the continental watershed and the Bitter-root Mountains has not been exactly surveyed. The average elevation above sea-level has been estimated at 3900 feet.

Topographically, Montana may be separated into two great divisions—that of the plains comprising the eastern two-thirds, and that of the mountains comprising the western portion. The former, a monotonous rolling expanse, broken only by the beds of the few streams which traverse it, and by a few small groups of hills, extends over nine degrees of longitude in a gentle uniform slope, rising from 2000 feet above the sea at the eastern boundary to 4000 at the base of the Rocky Mountains. Except along the streams and upon the scattered groups of hills, this section is entirely devoid of forest-growth of any kind. Vegetation is limited to the bunch grasses, artemisia, and cacti. The grasses are the most abundant and luxuriant near the mountains, where the rainfall is greatest. The mountain section, comprising the western third of the Territory, is composed, in general terms, of a succession of ranges and valleys running very uniformly somewhat in a north-west and south-east direction. The mountains vary in height from 8000 to 10,000, even in isolated cases reaching 11,000 feet, with mountain-passes 6000 to 8000 feet above the sea. Towards the north the ranges become almost continuous, forcing the streams into long and circuitous courses in order to disentangle themselves from the maze of mountains, while, on the other hand, the ranges of the south-western part of the Territory are much broken, affording numerous low passes and water-gaps.

In the mountainous part of the Territory are the head waters of the Missouri (Atlantic basin) and Clark's Fork of the Columbia (Pacific basin). The former rises in the south-west of the territory in three large branches, the Jefferson, Madison, and Gallatin, which meet at the foot of the Gallatin valley at a point known as the “Three Forks of the Missouri.” Here the Missouri is a good-sized stream, fordable with difficulty even when the current is lowest. From this point to its mouth navigation is possible when the stream is not below its mean height; it is interrupted only at the Great Falls of the Missouri, near Fort Benton, above which, however, it is practically little used for navigation. Its other principal tributaries in its upper course are the Sun, Teton, Marias, Musselshell, and Milk rivers, all of which vary much in size with the season,—the last two being nearly or quite dry near their mouths in the fall of the year. The Yellowstone, one of the most important tributaries of the Missouri, has nearly all its course in Montana, and is navigable for small steamers as far as the Crow Agency, except when the water is low. Clark's Fork of the Columbia is formed by the junction of the Flathead and the Missoula or Hellgate river. The former rises in the mountains of British Columbia and flows nearly south through Flathead Lake to its point of junction with the Missoula. The latter rises opposite the Jefferson river and flows north-westward, receiving on its way several large affluents. Below the point of junction of these streams, Clark's Fork flows north-west along the base of the Bitter-root Mountains into Idaho. This stream is very rapid, and is not navigable. Its course, as well as those of most of its tributaries, passes through narrow valleys, the surrounding country being well watered and covered with dense forests of Coniferæ.

Geology.—Most of the mountain area belongs to the Eozoic and Silurian formations. Along the base of the mountains is a Triassic belt of variable width. Succeeding this is a broad area of nearly horizontal Cretaceous beds, followed by the Tertiary formation, which covers nearly one-third of the Territory. These recent formations are interrupted here and there by volcanic upheavals.

Climate.—The climate of Montana differs almost as greatly in different parts of the Territory as that of California. In the north-west it resembles that of the Pacific coast. The westerly winds blowing off the Pacific do not meet with as formidable a barrier as farther south, and consequently are not chilled, or deprived of so large a proportion of their moisture. The result is that the north-western portion of Montana enjoys a mild temperature and a rainfall sufficient for the needs of agriculture. The valleys of the Kootenai, Flathead, Missoula, and Bitter-root can be cultivated without

irrigation with little danger of loss from drought. Farther east and south the rainfall decreases. In the valleys of the upper Missouri, the Jefferson, Madison, Gallatin, and the upper Yellowstone irrigation is almost everywhere required, as well as over the broad extent of the plains. Over most of the Territory the rainfall ranges from 10 to 15 inches annually; in the north-western corner it rises to 25.

The general temperature is comparatively mild for the latitude, the elevation above the sea being decidedly less than that of the average of the Rocky Mountain region. The mean annual temperature ranges from 40° to 50° Fahr., but the variations are very great and violent. Frosts and snowstorms are possible during every month of the year, so that agriculture and stock-raising are more or less hazardous. On the other hand, the ordinary extremes of temperature are not so great as in more arid portions of the country.

Forests.—Throughout the Territory, as everywhere else in the Cordilleran region, forests follow rainfall. The plains are treeless; the mountain valleys about the heads of the Missouri are clothed only with grass and artemisia, many localities extending to a considerable height up the mountains, which are themselves timbered, though not heavily. In the north-western part, roughly defined as the drainage area of Clark's Fork, where the rainfall is somewhat greater, the forests become of importance. The mountains are

forest-clad from summit to base; and the narrower valleys are also covered, while the timber is of larger size and of much greater commercial value than elsewhere in the Territory,—the valuable timber consisting entirely of the various species of Coniferæ, pine, fir, cedar, &c. Of the broad-leaved species, willow, aspen, and cotton-wood are abundant.

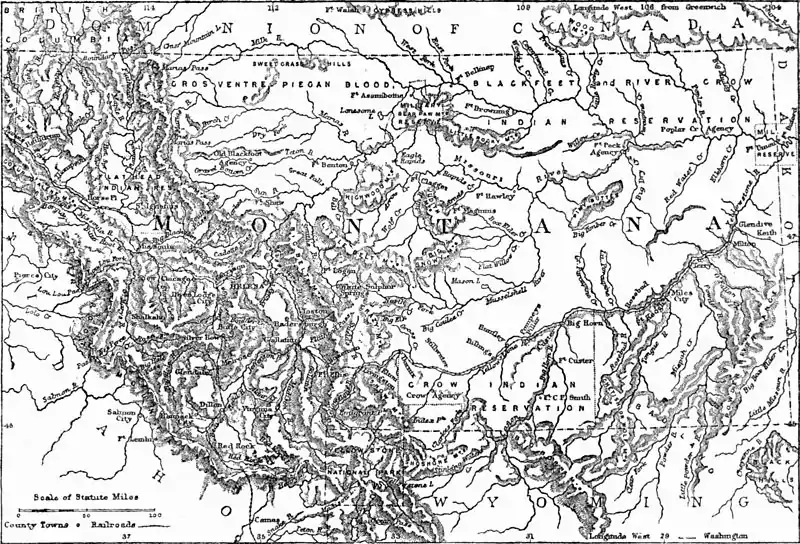

Sketch Map of Montana Territory.

Fauna.—The native fauna is not sharply distinguished from that of neighbouring States and Territories. The higher latitude is, however, indicated by the relatively greater abundance of species favouring a colder climate. The moose and the Rocky Mountain goat, though by no means abundant, still frequent chosen haunts in the mountains,—the former in the cool marshy valleys, the latter upon the most rugged inaccessible elevations. The black-tailed and mule deer, the antelope, elk, and mountain sheep are abundant, and the bison still ranges the plains, though in sadly reduced numbers. Among Carnivoræ, the black and grizzly bears, mountain lion, lynx, wild cat, and several species of wolves are still plentiful.

Agriculture and Industry. Agriculture is dependent in most parts of Montana upon the supply of water furnished by the streams. Owing to this fact it is probable that not more than 8 per cent. of the total area of the Territory can ever, even under the most economical distribution of the water-supply, be brought under cultivation. In the drainage area of Clark's Fork are

several fine valleys containing a considerable extent of arable land, such as those of the Missoula, Bitter-root, Deer Lodge, Jocko, and Flathead. Upon the head-waters of the Missouri is also a large extent of arable land. The valleys of the Jefferson and Madison also deserve mention. Along the eastern base of the mountains, near the head-waters of the Sun, Teton, and Marias rivers, are considerable areas susceptible of irrigation. Below the Forks the Missouri flows for 75 miles through a broad valley, much of which can be irrigated; below Fort Benton, however, the bluffs become higher and close in on the river. The Yellowstone, also, after leaving the mountains, flows through a similar kind of valley, which extends with a few minor breaks down to the point where the river turns from an east to a north-east course, when it enters a country of mauvaises terres, which, except as a mausoleum of fossil remains, is utterly valueless.

Owing to the comparatively isolated position of the Territory, agricultural pursuits have been limited by the demands of home consumption. The census of 1880 reported the area in farms to consist of 405, 683 acres, with an average of 267 acres to each farm. The whole is less than one-half per cent, of the entire area of the Territory. The improved land is reported as amounting to 262,611 acres. The following are the amounts of the principal agricultural products:—wheat, 469,688 bushels; maize, 5689 bushels; oats,

900,915 bushels; barley, 39,970 bushels; hay, 63,947 tons; wool, 995,484 pounds;—value of all farm products, $2,024,923. The live-stock interest is large, and is increasing rapidly. The great extent of pasture afforded by the plains and the broad valleys of the mountains would seem to promise an almost unlimited extension of this industry in the future. Both cattle and sheep owners, however, labour under disadvantages as compared with the owners farther south. The lower temperature and heavier snows, and particularly the danger of great extremes of temperature, require that provision of shelter and food be made for a part or all of the winter season, otherwise the rancheman runs the risk of occasional severe losses. The census of 1880 furnishes the following statistics of live-stock:—horses, 35,114; mules and asses, 858; working oxen, 936; milch cows, 11,308; other cattle, 160,143; sheep, 184,277; swine, 10,278;—total value of live-stock, $5,151,554.

In mineral production Montana has never taken a leading place, although in the early days some of the placer ground yielded well. The rich placers of Little Prickly Pear, Bannack, and Alder Gulch were quickly exhausted. The produce of the latter has been reported variously at from $25,000,000 to $40,000,000, the greater part of which was extracted in a few months. In the year 1879-80 $1,805,767 worth of gold and $2,905,068 of silver were extracted, about three-fourths from deep mines and one-fourth from placers. For the year 1882 the total mineral production is reported at $8,004,000, of which about $1,000,000 was for copper and lead.

Population.—Owing largely to its remote position the population as well as the material prosperity of Montana have had a slow growth in comparison with other more favoured portions of the west. The population in 1880, as reported by the census, was 39,159 (28,177 males, and 10,982 females),—an increase of 90.1 per cent. over that in 1870. There were 27,638 natives, and 11,521 of foreign birth, while 35,385 were whites, 346 negroes or of mixed negro blood, 1765 Chinese, and 1663 citizen Indians. By far the greater portion of the population is found in the western half, upon the head-waters of the Missouri and Clark's Fork. The eastern half is as yet but very sparsely settled, and probably it will never sustain more than a small population.

The Territory is divided into eleven counties, which, with their population in 1880, were the following:—Beaverhead, 2712; Choteau, 3058; Custer, 2510; Dawson, 180; Deer Lodge, 8876; Gallatin, 3643; Jefferson, 2464; Lewis and Clark, 6521; Madison, 3915; Meagher, 2743; Missoula, 2537. The principal settlements are—Helena, the capital (3624); Butte, a mining town (3363); and Bozeman, in the Gallatin valley upon the Northern Pacific Railway, which in 1880 had a population of 894 and has probably double that number at present (1883).

The total number of Indians in Montana is estimated by the Indian office at 19,764. These are nominally congregated at five agencies, although in reality they roam over the entire Territory. They are of various tribes, the principal of which are the Sioux, Crow, Blackfoot, Gros Ventre, Assinaboine, and Pend' d'Oreille. Their reservations cover more than one-third of the Territory.

Government and Finance.—The government of Montana is similar to that of the other Territories. The governor, secretary, chief justice, and two associate justices are appointed by the president of the United States. The treasurer, auditor, and superintendent of public instruction are elected by the people of the Territory, as are also the members of the two houses of the legislature. Montana is represented in Congress by a delegate, also elective, who has liberty to take part in debate but has no vote. The Territorial debt at the close of 1881 was but $70,000. The amount raised by Territorial taxation was $93,211.

History.—The Montana country was originally acquired by the United States under the Louisiana purchase. It became successively a part of Louisiana Territory, of Missouri Territory, of Nebraska Territory, and of Dakota. On 26th May 1864 it was organized under a Territorial government of its own, with practically its present boundaries. The exploration of this region commenced with the celebrated expedition of Lewis and Clark in 1803-1806. Between 1850 and 1855 it was traversed and mapped by a number of exploring parties, having in view the selection of trans-continental railroad routes. Since then numberless expeditions have examined it, and some systematic topographic work has been done under different branches of the United States Government. The first settlers entered the Territory in 1861, discovered placer gold on Little Prickly Pear Creek, and shortly after built the city of Helena. Later, the placers at Bannack were discovered, and a small “rush” to the Territory commenced. In 1863 the rich placers at Alder Gulch were brought to view, and miners and adventurers swarmed in from all parts. Then it was that the early social history of California was repeated on a smaller scale in Montana. The lawless elements assumed control, and for many months neither life nor property was safe. Indeed, for a time the community was in a state of blockade; no one with money in his possession could get out of the Territory. Finally, the citizens organized a “Vigilance Committee” for self-preservation, took the offensive, and after a short sharp struggle rid the community of its disturbing elements. After the exhaustion of the placers, the population decreased, owing

to the migration of the floating mining class; but their place was soon taken by more permanent settlers. (H. G*.)