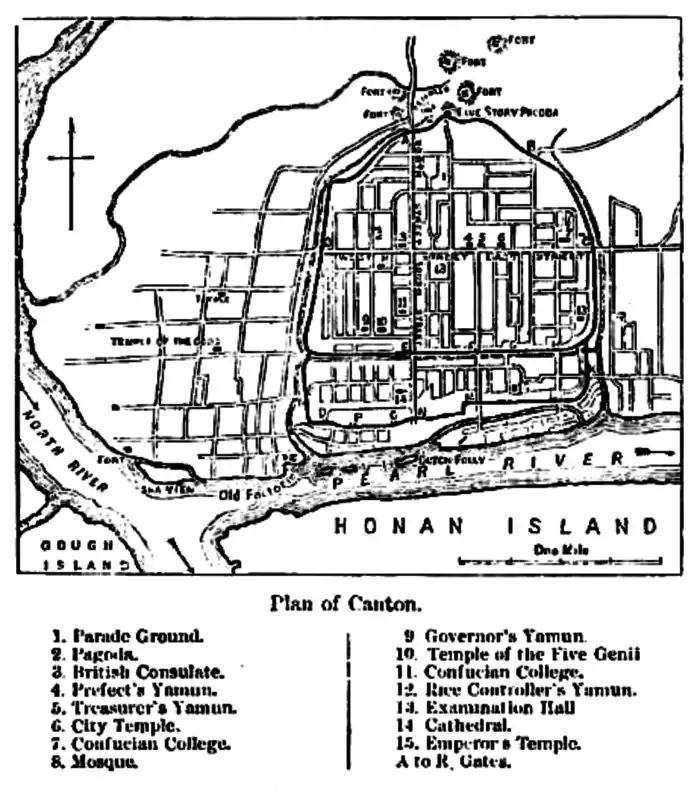

CANTON, or more correctly Kwang-chow Foo, is a large and populous commercial city of China, in the province of Kwang-tung, situated on the eastern bank of the Pearl River, which at Canton is somewhat broader than the Thames at London Bridge, and is navigable 300 miles farther into the interior. The Pearl River has an additional course of 80 miles to the sea, the first part of which lies through a rich alluvial plain. Beyond this rises a range of hills terminating in abrupt escarpments along the course of the river. The bold shore thus formed compresses the stream at this point into a narrow pass, to which the Chinese have given the name of Hu-mun, or Tiger's mouth. This the Portuguese translated into Boca Tigre, whence the designation of “the Boque," by which it is commonly known among Europeans. When viewed from the hills on the north, Canton appears to be little more than an expanse of reddish roofs relieved by a few large trees,—two pagodas shooting up within the walls, and a five-storied tower near the northern gate, being the most conspicuous objects. These hills rise 1200 feet above the river. Little or no vegetation is seen on them; and their acclivities, covered for miles with graves and tombs, serve as the necropolis of this vast city. Three or four forts are built on the points nearest the northern walls. Facing the city on the opposite side of the river is the suburb and island of Honan. The part of Canton enclosed by walls is about six miles in circumference, and has a partition wall, running east and west, and dividing the city into two unequal parts. The northern and larger division is called the old, and the southern the new city. Including the suburbs, the city has a circuit of nearly ten miles. The houses stretch along the river for four miles, and the banks are almost entirely concealed by boats and rafts. The walls of the city are of brick, on a foundation of sandstone and granite, are 20 feet thick, and rise to an average height of 25 feet. On the north side the wall rises to include a hill which it there meets with, and on the other three sides the city is surrounded by a ditch, which is filled by the rising tide, when, for a time, the revolting mass of filth that lies in its bed is concealed from view. There are twelve outer gates—four of which are in the partition wall, and two water gates, through which boats pass from east to west across the new city. The gates are all shut at night, and in the day time a guard is stationed at them to preserve order. The streets, amounting in all to upwards of 600, are long, straight, and very narrow. They are mostly paved and are not as dirty as those of some of the other cities in the empire; in fact, considering the habits of the people and the inattention of Government to these matters, Canton may be said to be a well-governed and comparatively cleanly city. The houses are in general small, seldom consisting of more than two stories, the ground floor serving as a shop in which goods are exhibited for sale, and the rest of the house, with the court behind, being used as a warehouse. Here are to be found the productions of every quarter of the globe; and the merchants are in general extremely attentive and civil. The Chinese are remarkably expert men of business, and are generally of the most assiduous habits.

| ||

The temples and public buildings of Canton are numerous, but none of them present features worthy of special remark. There are two pagodas near the west gate of the old city, and 124 temples, pavilions, halls, and other religious edifices within the city. One of the pagodas called the Kwangtah, or Plain Pagoda, is a Mahometan mosque, which was erected by the Arabian voyagers who were in the habit of visiting Canton about ten centuries ago. It rises in an angular tapering tower to the height of 160 feet. The other is an octagonal pagoda of nine stories, 170 feet in height, and was first erected more than thirteen centuries ago. A Buddhist temple at Honan, opposite the foreign factories, and named in Chinese Hai-chwang-sze, or the Temple of the Ocean Banner, is one of the largest in Canton. Its grounds, which cover about seven acres, are surrounded by a wall, and are divided into courts, gardens, and a burial-ground, where are deposited the ashes of priests, whose bodies are burned. There are about 175 priests connected with this establishment. Besides the Hai-chwang-sze the most noteworthy temples in and about the city are those of the Five Hundred Gods, and of Longevity, both in the western suburbs; the Tartar City Temple, and the Temple of the Five Genii. The number of priests and nuns in Canton is not exactly known, but they probably exceed 2000, nine-tenths of whom are Buddhists. The temples are gloomy-looking edifices. The areas in front of them are usually occupied by hucksters, beggars, and idlers, who are occasionally driven off to make room for the mat-sheds, in which the theatrical performances got up by the wealthy inhabitants are acted. The principal hall, where the idol sits enshrined, is lighted only in front, and the inner apartments are inhabited by a class of men almost as senseless as the idols they serve.

Formerly only a limited number of merchants, called the hong or security merchants, were allowed to trade with foreigners. They were commonly men of large property, and were famed for integrity in their transactions. All foreign cargoes passed through the hands of these merchants, and by them also the return cargoes were furnished. They became security for the payment of customs duties, and it was criminal for any other merchant to engage in the trade with foreigners.

Accounts are kept at Canton, in common with the rest of China, in taels, mace, candarines, and cash,—ten cash being one candarine, ten candarines one mace, ten mace one tael, which last is converted into English money at about 6s. 8d. The coin called cash is of base metal, cast, not coined, and very brittle. It is of small value, and varies in the market from 750 to 1000 cash for a tael. Its chief use is in making small payments among the lower classes. Spanish and other silver coins are current, and are estimated by their weight, every merchant carrying scales and weights with him. All the dollars that pass through the hands of the hong merchants bear their stamp; and when they lose their weight in the course of circulation they are cut in pieces for small change. The duties are paid to Government in sycee, or pure silver, which is taken by weight. In delivering a cargo, English weights and scales are used, which are afterwards reduced to Chinese catties and peculs. A pecul weighs 133⅓ ℔ avoirdupois, and a catty 1⅓ ℔. Gold and silver are also weighed by the tael and catty, 100 taels being reckoned equal to 120 oz. 16 dwt. troy.

The foreign trade at Canton was materially damaged by the opening of Shanghai and the ports on the Yang-tsze, but it is yet of very considerable importance, as the subjoined table of the total value of the foreign trade with Canton between the years 1861 and 1874 inclusive is sufficient to show:—

| Year. | Total Value of Imports. |

Total Value of Exports. |

Total Value. |

| Dollars. | Dollars. | Dollars. | |

| 1861 | 12,977,353 | 15,811,512 | 28,788,865 |

| 1862 | 10,580,928 | 17,742,590 | 28,323,518 |

| 1863 | 9,505,285 | 16,083,062 | 25,588,347 |

| 1864 | 8,192,795 | 13,659,177 | 21,851,972 |

| 1865 | 10,556,602 | 18,054,557 | 28,611,159 |

| 1866 | 14,171,101 | 18,832,622 | 33,003,723 |

| 1867 | 14,090,581 | 18,403,154 | 32,493,735 |

| 1868 | 12,991,266 | 18,491,156 | 31,482,422 |

| 1869 | 11,487,679 | 20,010,626 | 31,498,305 |

| 1870 | 12,053,394 | 19,857,543 | 31,910,937 |

| 1871 | 15,661,889 | 23,612,439 | 39,274,328 |

| 1872 | 16,802,553 | 25,691,712 | 42,494,265 |

| Shanghai Taels. | Shanghai Taels. | Shanghai Taels. | |

| 1873 | 9,843,819 | 16,156,437 | 26,900,256 |

| 1874 | 9,499,447 | 16,640,525 | 26,139,972 |

Although it is in the same parallel of latitude as Calcutta, the climate of Canton is much cooler, and is considered superior to that of most places situated between the tropics. The extreme range of the thermometer is from 38° to 100° Fahr., though these extremes are rarely reached. In ordinary years the winter minimum is about 42°, and the maximum in summer 96°. From May to October the hot season is considered to last; during the rest of the year the weather is cool. In shallow vessels ice sometimes forms at Canton; and so rarely is snow seen that when in February 1835 a fall to the depth of two inches occurred, the citizens hardly knew its proper name. Most of the rain falls during May and June, but the amount is nothing in comparison with that which falls during a rainy season in Calcutta. July, August, and September are the regular monsoon months, the wind coming from the south-west with frequent showers, which allay the heat. In the succeeding months the northerly winds commence, with some interruptions at first, but from October to January the temperature is agreeable, the sky clear, and the air invigorating. Few large cities are more generally healthy than Canton, and epidemics rarely prevail there.

Provisions and refreshments of all sorts are abundant, and in general are excellent in quality and moderate in price. It is a singular fact, that the Chinese make no use of milk, either in its natural state, or in the form of butter or cheese. Among the delicacies of a Chinese market are to be seen horse-flesh, dogs, cats, hawks, owls, and edible birds'-nests. The business between foreigners and natives at Canton is generally transacted in a jargon known as “Pigeon English,” the Chinese being extremely ready in acquiring a sufficient smattering of English words to render themselves intelligible.

The intercourse between China and Europe by the way of the Cape of Good Hope began in 1517, when Emmanuel, king of Portugal, sent an ambassador, accompanied by a fleet of eight ships, to Peking, on which occasion the sanction of the emperor to establish a trade at Canton was obtained. It was in 1596, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, that the English first attempted to open an intercourse with China, but ineffectually, for the two ships which were despatched on this mission were lost in the outward voyage, and it was not till about 1634 that English ships visited Canton. Unfortunately at this time a misunderstanding having occurred with the Chinese authorities owing to the treachery of the Portuguese, a rupture and a battle took place, and it was with difficulty that peace was again restored. In 1673 China was again visited by an English ship which was subsequently refused admission into Japan, and in 1677 a factory was established at Amoy. But during an irruption of the Tatars three years later this building was destroyed, and it was not till 1685 that the emperor permitted any trade with Europeans at that port. Upon the union of the two East India Companies in London, an imperial edict was issued, restricting the foreign commerce to the port of Canton.

On the conclusion of peace it became necessary to provide a foreign settlement for the merchants whose “factories” had been destroyed, and after some consultation it was determined to fill in and appropiate as the British settlement an extensive mud flat lying to the westward of the old factory site, and known as Sha-mien, or “The Sand Flats.” This site having been leased, it was converted into an artificial island by building a massive embankment of granite in an irregular oval form. Between the northern face of the site and the Chinese suburb, a canal of 100 feet in width was constructed, thus forming an island of about 2850 feet in length and 950 feet in greatest breadth. The expense of making this settlement was 325,000 Mexican dollars, four-fifths of which were defrayed by the British Government, and one-fifth by the French Government. The British portion of the new settlement was laid out in eighty-two lots; and so bright appeared the prospect of trade at the time of their sale that 9000 dollars and upwards was paid in more than one instance for a lot, with a river frontage, measuring 12,645 square feet. The depression in trade, however, which soon followed acted as a bar to building, and it was not until the British consulate was erected in 1865 that the merchants began to occupy the settlement in any numbers. The British consulate occupies six lots, with an area of 75,870 square feet in the centre of the site, overlooking the river, and is enclosed with a substantial wall. A ground-rent of 15,000 cash (about £3) per mow (a third of an acre) is annually paid by the owners of lots to the Chinese Government.

The Sha-mien settlement possesses many advantages. It is close to the western suburb of Canton, where reside all the wholesale dealers as well as the principal merchants and brokers; it faces the broad channel known as the Macao Passage, up which the cool breezes in summer are wafted almost uninterruptedly, and the river opposite to it affords a safe and commodious anchorage for steamers up to 1000 tons burden. Steamers only are allowed to come up to Canton, sailing vessels being restricted to the anchorage at Whampoa. See China.

(r. k. d.)