MOTHER'S PET

HERE was once a man and his wife who had three sons. The two oldest were tall, strong boys, who helped their father every day in his work, but the youngest was small and sickly, and as he stayed at home most of the time, hanging about his mother, they called him "Mother's Pet." At last the father died, and not long after the mother was taken sick. When she felt that death was near she called her youngest boy to her bedside, and said, sadly: "What will become of you, Mother's Pet, when I am gone? Your brothers are big enough to help themselves, but you are so small and weak!"

HERE was once a man and his wife who had three sons. The two oldest were tall, strong boys, who helped their father every day in his work, but the youngest was small and sickly, and as he stayed at home most of the time, hanging about his mother, they called him "Mother's Pet." At last the father died, and not long after the mother was taken sick. When she felt that death was near she called her youngest boy to her bedside, and said, sadly: "What will become of you, Mother's Pet, when I am gone? Your brothers are big enough to help themselves, but you are so small and weak!"

"I shall have no trouble," answered the lad. "You need not be worried about that."

So the mother died and was buried. Now the oldest son took possession of the house, and the second oldest took everything that remained.

"What, shall I have?" asked Mother's Pet.

"Well, well," said the eldest. "We forgot you Let us see—yes, you may have the kneading-trough, though. If you can obtain flour and yeast, you may bake dough-nuts and cakes every day, and live like a king."

So Mother's Pet got the kneading-trough, and nothing else. He was satisfied, however, and possessing himself of his heritage, carried it to the sea, where he launched the trough as a boat and put to sea, intending to try his luck in the wide world. When the wind and waves had tossed him about for several days, at length Mother's Pet arrived at a strange land, where he went ashore, bent upon making headway for the king's residence, where he intended to offer his service. Having walked about for several days, he arrived at his destination and went straight to the king.

"What is your name?" asked the stately monarch.

"My name is Mother's Pet. Will you not engage my service?"

"You don't look able to work," remarked the king. "In fact, you are too small and weak."

"I know I am small," replied the lad, "but doesn't your majesty know that a little one may often do a thing before a big fellow can turn around?"

"There you are right," returned the king. "Let us see—yes, chattering you seem to understand well enough, but very little besides, so we'll put you in among the girls in the kitchen."

"That is a start," said Mother's Pet. "Of course, I should like a better position and a good salary, but so far I am willing to excuse your majesty."

"I am much obliged to you," answered the king—"very much, indeed. If the occasion arises, I'll know where to find you."

"All right," said Mother's Pet. "When you want a good prime-minister, or general, or admiral, just notify me, and I'll be ready."

"You are very kind," replied the king, bowing him out, "and I hope you will call on me for anything you need."

So Mother's Pet entered the service of the king.

Now this monarch had a very pretty daughter. She was, of course, sought by a great many suitors; in fact, princes and dukes and noblemen swarmed about her like insects about a light.

The princess was sorely troubled about this, as she cared little or nothing for these men who did nothing but idle away their time for her sake, leaving her alone not a single moment of the day, although she tried all possible means to avoid them. One day she came into the kitchen and told the girls of her troubles. None of them understood her, however, as they all considered it pleasant to have a large number of suitors, and would be happy to marry a prince or a duke, or some great nobleman. The only person about the kitchen who sympathized with the princess was Mother's Pet. He happened to recollect an old story that his mother had once told him, and this he decided to use for the purpose of assisting the young lady to get rid of the many suitors surrounding her court.

The princess became greatly surprised when the lad beckoned her to follow him into the pantry. She complied, however, and when Mother's Pet had closed the door after them he said to her: "Shall I tell you how to get rid of your suitors?" "I wish you would," replied the sweet princess. "Listen," pursued Mother's Pet, "and mark my words! Tell them you are willing to marry any one of them who brings you a hen which lays golden eggs, a golden hand-mill which grinds by itself, and a golden lantern which can light up the whole kingdom."

On hearing this the princess became much pleased; she thanked the boy for his good advice, and afterwards she told her suitors what she expected them to do before she could ever think of giving to any of them her hand in marriage. When a week had passed, every prince, duke, and count had left the palace.

A year passed, but the princess was by no means as merry as of old, and the king, her father, began to feel vexed with the girl, who seemed determined to become an old maid. One day he called her and inquired who had advised her in regard to the hen, the mill, and the lantern. She told him of the boy in the kitchen, who had advised her so well. Upon this her father called him into his presence, and said that if he could not himself procure the three treasures he would be hanged by the neck until he was dead.

"Will I be allowed to marry the princess if I find them?" asked the boy.

"I can safely promise you that," replied the king.

Now the story that the boy remembered was about a troll who lived far away, hundreds of leagues beyond the sea, and who possessed three costly treasures—those, in fact, which he had mentioned to the princess. So he hastened to the beach and put to sea in his kneading-trough.

Having completed his voyage he stepped ashore, and repaired to the house where the troll and his wife were living. As soon as it became dark he mounted the roof of the house and opened a trap-door through which he descended. On the collar-beam the magic hen was perched, so the boy, who knew that caution was necessary, stole silently up to her from behind, and managed to throw his cap over her. But the hen made such a violent effort to gain its liberty, and bragged so loudly, that the troll awoke. The boy climbed down and ran to his boat. The troll, running after him, reached the beach, but the boy was already far out to sea when he reached the water's edge.

"Did you steal my hen?" cried the troll.

"Yes, I did," returned Mother's Pet.

"Will you return?"

"Depend upon it."

"Then I shall catch you," shouted the troll, "and eat you up!"

The king and the princess were well pleased with the wonderful hen with which the boy

"BOTH KNELT DOWN AND DRANK"

But in a few days he decided to return for the hand-mill and the lantern.

Having reached the troll's house safe and sound, he hid among the trees in the garden until midnight, when he again ascended to the house armed with a heavy club. When he opened the trap-door he could hear the troll and his wife snoring so loudly that every door and window rattled. Now Mother's Pet reached through the opening with his club, and let it fall exactly on the troll's large nose. He awoke immediately, kicked his wife far out on the floor, and asked what she meant by breaking his nasal bone. The woman protested, but in vain; her husband insisted that she had intended to murder him. They very soon came to blows, and while they tumbled out of the door to fight, Mother's Pet stole through the opening, seized the hand-mill and the lantern, which stood on a table near the bed, rushed out of the door, and made for his boat with all possible speed.

The troll's wife noticed the light which issued from the golden lantern, and shouted to her husband, who was beating her violently with the heavy club, "You had better look after our treasures! Some one is running away with them!" They both pursued the boy, but he had already reached his kneading-trough, and was far from the shore when they reached it.

"Are you called Mother's Pet?" cried the troll.

"Yes, I am," was the answer.

"Did you steal my golden hand-mill and my precious lantern?"

"Sure."

"Did you also steal my hen?"

"Who else could it be?"

"Will you return?"

"Yes, when the sea becomes a mountain!" shouted the boy, merrily.

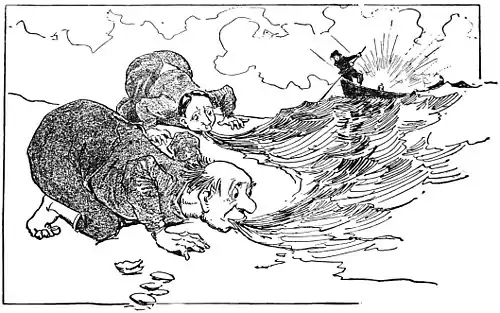

"Let us empty the sea," proposed the woman. Both knelt down, and drank with all their might until they became as thick and firm as a pair of drums. As the water in the sea rushed into their mouths with wonderful rapidity the waves rose as high as mountains, and in spite of every effort on his part the boy's trough rapidly approached the troll's mouth. But at the very moment when his large hand was stretched out to seize the frail boat both he and his wife burst. The water ran back into its cradle with such force that Mother's Pet, the trough, the hand-mill, and the lantern were pushed ashore on the other side, where the king and the princess stood watching for them. They all arrived safely, however, and there was a great joy throughout the land when the princess and Mother's Pet were married.

Mother's Pet became in time a great king. All his subjects were happy, for as the hen laid a golden egg every day there were no taxes to pay, and as the hand-mill provided for every one, all were well supplied with the necessities of life. The golden lantern provided so well for enlightenment that no more schools were needed, and this was the very best of it all—said the children!