BROTHER LEO

BY PHYLLIS BOTTOME

IT was a sunny morning, and I was on my way to Torcello. Venice lay behind us a dazzling line, with towers of gold against the blue lagoon. All at once a breeze sprang up from the sea; the small, feathery islands seemed to shake and quiver, and, like leaves driven before a gale, those flocks of colored butterflies, the fishing-boats, ran in before the storm. Far away to our left stood the ancient tower of Altinum, with the island of Burano a bright pink beneath the towering clouds. To our right, and much nearer, was a small cypress-covered islet. One large umbrella-pine hung close to the sea, and behind it rose the tower of the convent church. The two gondoliers consulted together in hoarse cries and decided to make for it.

"It is San Francesco del Deserto," the elder explained to me. "It belongs to the little brown brothers, who take no money and are very kind. One would hardly believe these ones had any religion, they are such a simple people, and they live on fish and the vegetables they grow in their garden."

We fought the crooked little waves in silence after that; only the high prow rebelled openly against its sudden twistings and turnings. The arrowy-shaped gondola is not a structure made for the rough jostling of waves, and the gondoliers put forth all their strength and skill to reach the tiny haven under the convent wall. As we did so, the black bars of cloud rushed down upon us in a perfect deluge of rain, and we ran speechless and half drowned across the tossed field of grass and forget-me-nots to the convent door. A shivering beggar sprang up from nowhere and insisted on ringing the bell for us.

The door opened, and I saw before me a young brown brother with the merriest eyes I have ever seen. They were unshadowed, like a child's, dancing and eager, and yet there was a strange gentleness and patience about him, too, as if there was no hurry even about his eagerness.

He was very poorly dressed and looked thin. I think he was charmed to see us, though a little shy, like a hospitable country hostess anxious to give pleasure, but afraid that she has not much to offer citizens of a larger world.

"What a tempest!" he exclaimed. "You have come at a good hour. Enter, enter, Signore! And your men, will they not come in?"

We found ourselves in a very small rose-red cloister; in the middle of it was an old well under the open sky, but above us was a sheltering roof spanned by slender arches. The young monk hesitated for a moment, smiling from me to the two gondoliers. I think it occurred to him that we should like different entertainment, for he said at last:

"You men would perhaps like to sit in the porter's lodge for a while? Our Brother Lorenzo is there; he is our chief fisherman, with a great knowledge of the lagoons; and he could light a fire for you to dry yourselves by—Signori. And you, if I mistake not, are English, are you not, Signore? It is probable that you would like to see our chapel. It is not much. We are very proud of it, but that, you know, is because it was founded by our blessed father, Saint Francis. He believed in poverty, and we also believe in it, but it does not give much for people to see. That is a misfortune, to come all this way and to see nothing." Brother Leo looked at me a little wistfully. I think he feared that I should be disappointed. Then he passed before me with swift, eager feet toward the little chapel.

It was a very little chapel and quite bare; behind the altar some monks were chanting an office. It was clean, and there were no pictures or images, only, as I knelt there, I felt as if the little island in its desert of waters had indeed secreted some vast treasure, and as if the chapel, empty as it had seemed at first, was full of invisible possessions. As for Brother Leo, he had stood beside me nervously for a moment; but on seeing that I was prepared to kneel, he started, like a bird set free, toward the altar steps, where his lithe young impetuosity sank into sudden peace. He knelt there so still, so rapt, so incased in his listening silence, that he might have been part of the stone pavement. Yet his earthly senses were alive, for the moment I rose he was at my side again, as patient and courteous as ever, though I felt as if his inner ear were listening still to some unheard melody.

We stood again in the pink cloister. "There is little to see," he repeated. "We are poverelli; it has been like this for seven hundred years." He smiled as if that age-long, simple service of poverty were a light matter, an excuse, perhaps, in the eyes of the citizen of a larger world for their having nothing to show. Only the citizen, as he looked at Brother Leo, had a sudden doubt as to the size of the world outside. Was it as large, half as large, even, as the eager young heart beside him which had chosen poverty as a bride?

The rain fell monotonously against the stones of the tiny cloister.

"What a tempest!" said Brother Leo, smiling contentedly at the sky. "You must come in and see our father. I sent word by the porter of your arrival, and I am sure he will receive you; that will be a pleasure for him, for he is of the great world, too. A very learned man, our father; he knows the French and the English tongue. Once he went to Rome; also he has been several times to Venice. He has been a great traveler."

"And you," I asked—"have you also traveled?"

Brother Leo shook his head.

"I have sometimes looked at Venice," he said, "across the water, and once I went to Burano with the marketing brother; otherwise, no, I have not traveled. But being a guest-brother, you see, I meet often with those who have, like your Excellency, for instance, and that is a great education."

We reached the door of the monastery, and I felt sorry when another brother opened to us, and Brother Leo, with the most cordial of farewell smiles, turned back across the cloister to the chapel door. "Even if he does not hurry, he will still find prayer there," said a quiet voice beside me.

I turned to look at the speaker. He was a tall old man with white hair and eyes like small blue flowers, very bright and innocent, with the same look of almost superb contentment in them that I had seen in Brother Leo's eyes.

"But what will you have?" he added with a twinkle. "The young are always afraid of losing time; it is, perhaps, because they have so much. But enter, Signore! If you will be so kind as to excuse the refectory, it will give me much pleasure to bring you a little refreshment. You will pardon that we have not much to offer?"

The father—for I found out afterward that he was the superior himself—brought me bread and wine, made in the convent, and waited on me with his own hands. Then he sat down on a narrow bench opposite to watch me smoke. I offered him one of my cigarettes, but he shook his head, smiling.

"I used to smoke once," he said. "I was very particular about my tobacco. I think it was similar to yours—at least the aroma, which I enjoy very much, reminds me of it. It is curious, is it not, the pleasure we derive from remembering what we once had? But perhaps it is not altogether a pleasure unless one is glad that one has not got it now. Here one is free from things. I sometimes fear one may be a little indulgent about one's liberty. Space, solitude, and love—it is all very intoxicating."

There was nothing in the refectory except the two narrow benches on which we sat, and a long trestled board which formed the table; the walls were white-washed and bare, the floor was stone. I found out later that the brothers ate and drank nothing except bread and wine and their own vegetables in season, a little macaroni sometimes in winter, and in summer figs out of their own garden. They slept on bare boards, with one thin blanket winter and summer alike. The fish they caught they sold at Burano or gave to the poor. There was no doubt that they enjoyed very great freedom from "things."

It was a strange experience to meet a man who never had heard of a flying-machine and who could not understand why it was important to save time by using the telephone or the wireless-telegraphy system; but despite the fact that the father seemed very little impressed by our modern urgencies, I never have met a more intelligent listener or one who seized more quickly on all that was essential in an explanation.

"You must not think we do nothing at all, we lazy ones who follow old paths," he said in answer to one of my questions. "There are only eight of us brothers, and there is the garden, fishing, cleaning, and praying. We are sent for, too, from Burano to go and talk a little with the people there, or from some island on the lagoons which perhaps no priest can reach in the winter. It is easy for us, with our little boat and no cares."

"But Brother Leo told me he had been to Burano only once," I said. "That seems strange when you are so near."

"Yes, he went only once," said the father, and for a moment or two he was silent, and I found his blue eyes on mine, as if he were weighing me.

"Brother Leo," said the superior at last, "is our youngest. He is very young, younger perhaps than his years; but we have brought him up altogether, you see. His parents died of cholera within a few days of each other. As there were no relatives, we took him, and when he was seventeen he decided to join our order. He has always been happy with us, but one cannot say that he has seen much of the world." He paused again, and once more I felt his blue eyes searching mine. "Who knows?" he said finally. "Perhaps you were sent here to help me. I have prayed for two years on the subject, and that seems very likely. The storm is increasing, and you will not be able to return until to-morrow. This evening, if you will allow me, we will speak more on this matter. Meanwhile I will show you our spare room. Brother Lorenzo will see that you are made as comfortable as we can manage. It is a great privilege for us to have this opportunity; believe me, we are not ungrateful."

It would have been of no use to try to explain to him that it was for us to feel gratitude. It was apparent that none of the brothers had ever learned that important lesson of the worldly respectable—that duty is what other people ought to do. They were so busy thinking of their own obligations as to overlook entirely the obligations of others. It was not that they did not think of others. I think they thought only of one another, but they thought without a shadow of judgment, with that bright, spontaneous love of little children, too interested to point a moral. Indeed, they seemed to me very like a family of happy children listening to a fairy-story and knowing that the tale is true.

After supper the superior took me to his office. The rain had ceased, but the wind howled and shrieked across the lagoons, and I could hear the waves breaking heavily against the island. There was a candle on the desk, and the tiny, shadowy cell looked like a picture by Rembrandt.

"The rain has ceased now," the father said quietly, "and to-morrow the waves will have gone down, and you, Signore, will have left us. It is in your power to do us all a great favor. I have thought much whether I shall ask it of you, and even now I hesitate; but Scripture nowhere tells us that the kingdom of heaven was taken by precaution, nor do I imagine that in this world things come oftenest to those who refrain from asking.

"All of us," he continued, "have come here after seeing something of the outside world; some of us even had great possessions. Leo alone knows nothing of it, and has possessed nothing, nor did he ever wish to; he has been willing that nothing should be his own, not a flower in the garden, not anything but his prayers, and even these I think he has oftenest shared. But the visit to Burano put an idea in his head. It is, perhaps you know, a factory town where they make lace, and the people live there with good wages, many of them, but also much poverty. There is a poverty which is a grace, but there is also a poverty which is a great misery, and this Leo never had seen before. He did not know that poverty could be a pain. It filled him with a great horror, and in his heart there was a certain rebellion. It seemed to him that in a world with so much money no one should suffer for the lack of it.

"It was useless for me to point out to him that in a world where there is so much health God has permitted sickness; where there is so much beauty, ugliness; where there is so much holiness, sin. It is not that there is any lack in the gifts of God; all are there, and in abundance, but He has left their distribution to the soul of man. It is easy for me to believe this. I have known what money can buy and what it cannot buy; but Brother Leo, who never has owned a penny, how should he know anything of the ways of pennies?

"I saw that he could not be contented with my answer; and then this other idea came to him—the idea that is, I think, the blessed hope of youth that this thing being wrong, he, Leo, must protest against it, must resist it! Surely, if money can do wonders, we who set ourselves to work the will of God should have more control of this wonder-working power? He fretted against his rule. He did not permit himself to believe that our blessed father, Saint Francis, was wrong, but it was a hardship for him to refuse alms from our kindly visitors. He thought the beggars' rags would be made whole by gold; he wanted to give them more than bread, he wanted, poverino! to buy happiness for the whole world."

The father paused, and his dark, thought-lined face lighted up with a sudden, beautiful smile till every feature seemed as young as his eyes.

"I do not think the human being ever has lived who has not thought that he ought to have happiness," he said. "We begin at once to get ready for heaven; but heaven is a long way off. We make haste slowly. It takes us all our lives, and perhaps purgatory, to get to the bottom of our own hearts. That is the last place in which we look for heaven, but I think it is the first in which we shall find it."

"But it seems to me extraordinary that, if Brother Leo has this thing so much on his mind, he should look so happy," I exclaimed. "That is the first thing I noticed about him."

"Yes, it is not for himself that he is searching," said the superior. "If it were, I should not wish him to go out into the world, because I should not expect him to find anything there. His heart is utterly at rest; but though he is personally happy, this thing troubles him. His prayers are eating into his soul like flame, and in time this fire of pity and sorrow will become a serious menace to his peace. Besides, I see in Leo a great power of sympathy and understanding. He has in him the gift of ruling other souls. He is very young to rule his own soul, and yet he rules it. When I die, it is probable that he will be called to take my place, and for that it is necessary he should have seen clearly that our rule is right. At present he accepts it in obedience, but he must have more than obedience in order to teach it to others; he must have a personal light.

"This, then, is the favor I have to ask of you, Signore. I should like to have you take Brother Leo to Venice to-morrow, and, if you have the time at your disposal, I should like you to show him the towers, the churches, the palaces, and the poor who are still so poor. I wish him to see how people spend money, both the good and the bad. I wish him to see the world. Perhaps then it will come to him as it came to me—that money is neither a curse nor a blessing in itself, but only one of God's mysteries, like the dust in a sunbeam."

"I will take him very gladly; but will one day be enough?" I answered.

The superior arose and smiled again.

"Ah, we slow worms of earth," he said, "are quick about some things! You have learned to save time by flying-machines; we, too, have certain methods of flight. Brother Leo learns all his lessons that way. I hardly see him start before he arrives. You must not think I am so myself. No, no. I am an old man who has lived a long life learning nothing, but I have seen Leo grow like a flower in a tropic night. I thank you, my friend, for this great favor. I think God will reward you."

Brother Lorenzo took me to my bedroom; he was a talkative old man, very anxious for my comfort. He told me that there was an office in the chapel at two o'clock, and one at five to begin the day, but he hoped that I should sleep through them.

"They are all very well for us," he explained, "but for a stranger, what cold, what disturbance, and what a difficulty to arrange the right thoughts in the head during chapel! Even for me it is a great temptation. I find my mind running on coffee in the morning, a thing we have only on great feast-days. I may say that I have fought this thought for seven years, but though a small devil, perhaps, it is a very strong one. Now, if you should hear our bell in the night, as a favor pray that I may not think about coffee. Such an imperfection! I say to myself, the sin of Esau! But he, you know, had some excuse; he had been hunting. Now, I ask you—one has not much chance of that on this little island; one has only one's sins to hunt, and, alas! they don't run away as fast as one could wish! I am afraid they are tame, these ones. May your Excellency sleep like the blessed saints, only a trifle longer!"

I did sleep a trifle longer; indeed, I was quite unable to assist Brother Lorenzo to resist his coffee devil during chapel-time. I did not wake till my tiny cell was flooded with sunshine and full of the sound of St. Francis's birds. Through my window I could see the fishing-boats pass by. First came one with a pair of lemon-yellow sails, like floating primroses; then a boat as scarlet as a dancing flame, and half a dozen others painted some with jokes and some with incidents in the lives of patron saints, all gliding out over the blue lagoon to meet the golden day.

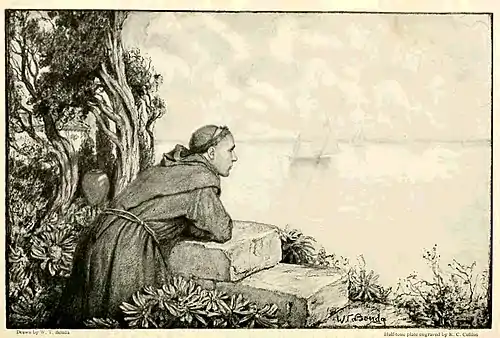

HE WAS LOOKING OUT OVER THE BLUE STRETCH OF LAGOON INTO THE DISTANCE, WHERE VENICE LAY LIKE A MOVING CLOUD AT THE HORIZON'S EDGE."

I rose, and from my window I saw Brother Leo in the garden. He was standing under St. Francis's tree—the old gnarled umbrella-pine which hung over the convent-wall above the water by the island's edge. His back was toward me, and he was looking out over the blue stretch of lagoon into the distance, where Venice lay like a moving cloud at the horizon's edge; but a mist hid her from his eyes, and while I watched him he turned back to the garden-bed and began pulling out weeds. The gondoliers were already at the tiny pier when I came out.

"Per Bacco, Signore!" the elder explained. "Let us hasten back to Venice and make up for the Lent we have had here. The brothers gave us all they had, the holy ones—a little wine, a little bread, cheese that could n't fatten one's grandmother, and no macaroni—not so much as would go round a baby's tongue! For my part, I shall wait till I get to heaven to fast, and pay some attention to my stomach while I have one." And he spat on his hands and looked toward Venice.

"And not an image in the chapel!" agreed the younger man. "Why, there is nothing to pray to but the Signore Dio Himself! Veramente, Signore, you are a witness that I speak nothing but the truth."

The father superior and Leo appeared at this moment down the path between the cypresses. The father gave me thanks and spoke in a friendly way to the gondoliers, who for their part expressed a very pretty gratitude in their broad Venetian patois, one of them saying that the hospitality of the monks had been like paradise itself, and the other hasting to agree with him.

The two monks did not speak to each other, but as the gondolier turned the huge prow toward Venice, a long look passed between them—such a look as a father and son might exchange if the son were going out to war, while his father, remembering old campaigns, was yet bound to stay at home.

It was a glorious day in early June; the last traces of the storm had vanished from the serene, still waters; a vague curtain of heat and mist hung and shimmered between ourselves and Venice; far away lay the little islands in the lagoon, growing out of the water like strange sea-flowers. Behind us stood San Francesco del Deserto, with long reflections of its one pink tower and arrowy, straight cypresses, soft under the blue water.

The father superior walked slowly back to the convent, his brown-clad figure a shining shadow between the two black rows of cypresses. Brother Leo waited till he had disappeared, then turned his eager eyes toward Venice.

As we approached the city the milky sea of mist retreated, and her towers sprang up to greet us. I saw a look in Brother Leo's eyes that was not fear or wholly pleasure; yet there was in it a certain awe and a strange, tentative joy, as if something in him stretched out to greet the world. He muttered half to himself:

"What a great world, and how many children il Signore Dio has!"

When we reached the piazzetta, and he looked up at the amazing splendor of the ducal palace, that building of soft yellow, with its pointed arches and double loggias of white marble, he spread out both his hands in an ecstasy.

"But what a miracle!" he cried. "What a joy to God and to His angels! How I wish my brothers could see this! Do you not imagine that some good man was taken to paradise to see this great building and brought back here to copy it?"

"Chi lo sa?" I replied guardedly, and we landed by the column of the Lion of St. Mark's. That noble beast, astride on his pedestal, with wings outstretched, delighted the young monk, who walked round and round him.

"What a tribute to the saint!" he exclaimed. "Look, they have his wings, too. Is not that faith?"

"Come," I said, "let us go on to Saint Mark's. I think you would like to go there first; it is the right way to begin our pilgrimage."

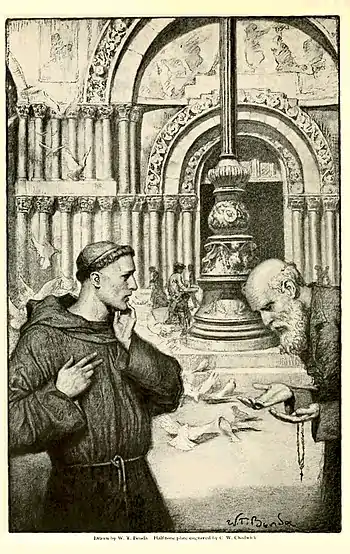

The piazza was not very full at that hour of the morning, and its emptiness increased the feeling of space and size. The pigeons wheeled and circled to and fro, a dazzle of soft plumage, and the cluster of golden domes and sparkling minarets glittered in the sunshine like flames. Every image and statue on St. Mark's wavered in great lines of light like a living pageant in a sea of gold.

Brother Leo said nothing as he stood in front of the three great doorways that lead into the church. He stood quite still for a while, and then his eyes fell on a beggar beside the pink and cream of the new campanile, and I saw the wistfulness in his eyes suddenly grow as deep as pain.

"Have you money, Signore?" he asked me. That seemed to him the only question. I gave the man something, but I explained to Brother Leo that he was probably not so poor as he looked.

"They live in rags," I explained, "because they wish to arouse pity. Many of them need not beg at all."

"Is it possible?" asked Brother Leo, gravely; then he followed me under the brilliant doorways of mosaic which lead into the richer dimness of St. Mark's.

When he found himself within that great incrusted jewel, he fell on his knees. I think he hardly saw the golden roof, the jeweled walls, and the five lifted domes full of sunshine and old gold, or the dark altars, with their mysterious, rich shimmering. All these seemed to pass away beyond the sense of sight; even I felt somehow as if those great walls of St. Mark's were not so great as I had fancied. Something greater was kneeling there in an old habit and with bare feet, half broken-hearted because a beggar had lied.

I found myself regretting the responsibility laid on my shoulders. Why should I have been compelled to take this Strangely innocent, sheltered boy, with his fantastic third-century ideals, out into the shoddy, decorative, unhappy world? I even felt a kind of anger at the simplicity of his soul. I wished he were more like other people; I suppose because he had made me wish for a moment that I was less like them.

"What do you think of Saint Mark's?" I asked him as we stood once more in the hot sunshine outside, with the strutting pigeons at our feet and wheeling over our heads.

Brother Leo did not answer for a moment, then he said:

"I think Saint Mark would feel it a little strange. You see, I do not think he was a great man in the world, and the great in paradise—" He stooped and lifted a pigeon with a broken foot nearer to some corn a passer-by was throwing for the birds. "I cannot think," he finished gravely, "that they care very much for palaces in paradise; I should think every one had them there or else—nobody."

I was surprised to see the pigeons that wheeled away at my approach allow the monk to handle them, but they seemed unaware of his touch.

"Poverino!" he said to the one with the broken foot. "Thank God that He has given you wings!"

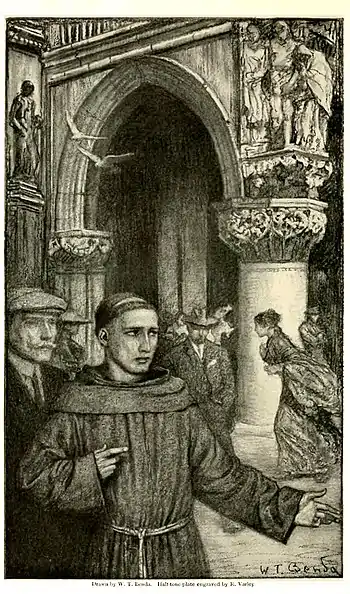

Brother Leo spoke to every child he met, and they all answered him as if there was a secret freemasonry between them; but the grown-up people he passed with troubled eyes.

"It seems strange to me," he said at last, "not to speak to these brothers and sisters of ours, and yet I see all about me that they do not salute one another."

"They are many, and they are all strangers," I tried to explain.

"Yes, they are very many." he said a little sadly. "I had not known that there were so many people in the world, and I thought that in a Christian country they would not be strangers."

HE STOOD QUITE STILL FOR A WHILE, AND THEN HIS EYES FELL ON A BEGGAR

I took another gondola by the nearest bridge, and we rowed to the Frari. I hardly knew what effect that great church, with its famous Titian, would have upon him. A group of tourists surrounded the picture. I heard a young lady exclaiming:

"My! but I'd like her veil! Ain't she cute, looking round it that way?"

Brother Leo did not pause; he passed as it by instinct toward the chapel on the right which holds the softest, tenderest of Bellini's. There, before the Madonna with her four saints and two small attendant cherubs, he knelt again, and his eyes filled with tears. I do not think he heard the return of the tourists, who were rather startled at seeing him there. The elder lady remarked that he might have some infectious disease, and the younger that she did not think much of Bellini, anyway.

He knelt for some time, and I had not the heart to disturb him; indeed, I had no wish to, either, for Bellini's "Madonna" is my favorite picture, and that morning I saw in it more than I had ever seen before. It seemed to me as if that triumphant, mellow glow of the great master was, an eternal thing, and as if the saints and their gracious Lady, with the stalwart, standing Child upon her knee, were more real than flesh and blood, and would still be more real when flesh and blood had ceased to be. I never have recaptured the feeling; perhaps there was something infectious about Brother Leo, after all. He made no comment on the Madonna, nor did I expect one, for we do not need to assert that we find the object of our worship beautiful; but I was amused at his calm refusal to look upon the great Titian as a Madonna at all.

"No, no," he said firmly. "This one is no doubt some good and gracious lady, but the Madonna! Signore, you jest. Or, if the painter thought so, he was deceived by the devil. Yes, that is very possible. The father has often told us that artists are exposed to great temptations: their eyes see paradise before their souls have reached it, and that is a great danger."

I said no more, and we passed out into the street again. I felt ashamed to say that I wanted my luncheon, but I did say so, and it did not seem in the least surprising to Brother Leo; he merely drew out a small wallet and offered me some bread, which he said the father had given him for our needs.

I told him that he must not dream of eating that; he was to come and dine with me at my hotel. He replied that he would go wherever I liked, but that really he would prefer to eat his bread unless indeed we were so fortunate as to find a beggar who would like it. However, we were not so fortunate, and I was compelled to eat an exceedingly substantial five-course luncheon while my companion sat opposite me and ate his halt loaf of black bread with what appeared to be appetite and satisfaction.

He asked me a great main questions about what everything in the room was used for and what everything cost, and appeared very much surprised at my answers.

"This, then," he said, "is not like all the other houses in Venice? Is it a special house—perhaps for the English only?"

I explained to him that most houses contained tables and chairs; that this, being a hotel, was in some ways even less furnished than a private house, though doubtless it was larger and was arranged with a special eye to foreign requirements.

"But the poor—they do not live like this?" Leo asked. I had to own that the poor did not. "But the people here are rich?" Leo persisted.

"Well, yes, I suppose so, tolerably well off," I admitted.

"How miserable they must be!" exclaimed Leo, compassionately. "Are they not allowed to give away their money?

This seemed hardly the way to approach the question of the rich and the poor, and I do not know that I made it any better by an after-dinner exposition upon capital and labor. I finished, of course, by saying that if the rich gave to the poor to-day, there would still be rich and poor to-morrow. It did not sound very convincing to me, and it did nothing whatever to convince Brother Leo.

"'IT SEEMS STRANGE TO ME NOT TO SPEAK TO THESE BROTHERS AND SISTERS'"

"That is perhaps true," he said at last. "One would not wish, however, to give all into unready hands like that poor beggar this morning who knew no better than to pretend in order to get more money. No, that would be the gift of a madman. But could not the rich use their money in trust for the poor, and help and teach them little by little till they learned how to share their labor and their wealth? But you know how ignorant am I who speak to you. It is probable that this is what is already being done even here now in Venice and all over the world. It would not be left to a little one like me to think of it. What an idea for the brothers at home to laugh at!"

"Some people do think these things," I admitted.

"But do not all?" asked Brother Leo, incredulously.

"No, not all," I confessed.

"Andiamo!" said Leo, rising resolutely. "Let us pray to the Madonna. What a vexation it must be to her and to all the blessed saints to watch the earth! It needs the patience of the Blessed One Himself, to bear it."

In the Palazzo Giovanelli there is one of the loveliest of Giorgiones. It is called "His Family," and it represents a beautiful nude woman with her child and her lover. It seemed to me an outrage that this young brother should know nothing of the world, of life. I was determined that he should see this picture. I think I expected Brother Leo to be shocked when he saw it. I know I was surprised that he looked at it—at the serene content of earth, its exquisite ultimate satisfaction—a long time. Then he said in an awed voice:

"It is so beautiful that it is strange any one in all the world can doubt the love of God who gave it."

"Have you ever seen anything more beautiful; do you believe there is anything more beautiful?" I asked rather cruelly.

"Yes," said Brother Leo, very quietly; "the love of God is more beautiful, only that cannot be painted."

After that I showed him no more pictures, nor did I try to make him understand life. I had an idea that he understood it already rather better than I did. When I took him back to the piazza, it was getting on toward sunset, and we sat at one of the little tables at Florian's, where I drank coffee. We heard the band and watched the slow-moving, good-natured Venetian crowd, and the pigeons winging their perpetual flight.

All the light of the gathered day seemed to fall on the great golden church at the end of the piazza. Brother Leo did not look at it very much; his attention was taken up completely in watching the faces of the crowd, and as he watched them I thought to read in his face what he had learned in that one day in Venice—whether my mission had been a success or a failure; but, though I looked long at that simple and childlike face, I learned nothing.

What is so mysterious as the eyes of a child?

But I was not destined to part from Brother Leo wholly in ignorance. It was as if, in his open kindliness of nature, he would not leave me with any unspoken puzzle between us. I had been his friend and he told me, because it was the way things seemed to him, that I had been his teacher.

We stood on the piazzetta. I had hired a gondola with two men to row him back; the water was like beaten gold, and the horizon the softest shade of pink. "This day I shall remember all my life," he said, "and you in my prayers with all the world—always, always. Only I should like to tell you that that little idea of mine, which the father told me he had spoken to you about, I see now that it is too large for me. I am only a very poor monk. I should think I must be the poorest monk God has in all His family of monks. If He can be patient, surely I can. And it came over me while we were looking at all those wonderful things, that if money had been the way to save the world, Christ himself would have been rich. It was stupid of me. I did not remember that when he wanted to feed the multitude, he did not empty the great granaries that were all his, too; he took only five loaves and two small fishes; but they were enough.

"We little ones can pray, and God can change His world. Speriamo!" He smiled as he gave me his hand—a smile which seemed to me as beautiful as anything we had seen that day in Venice. Then the high-prowed, black gondola glided swiftly out over the golden waters with the little brown figure seated in the smallest seat. He turned often to wave to me, but I noticed that he sat with his face away from Venice.

He had turned back to San Francesco del Deserto, and I knew as I looked at his face that he carried no single small regret in his eager heart.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1963, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 50 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.