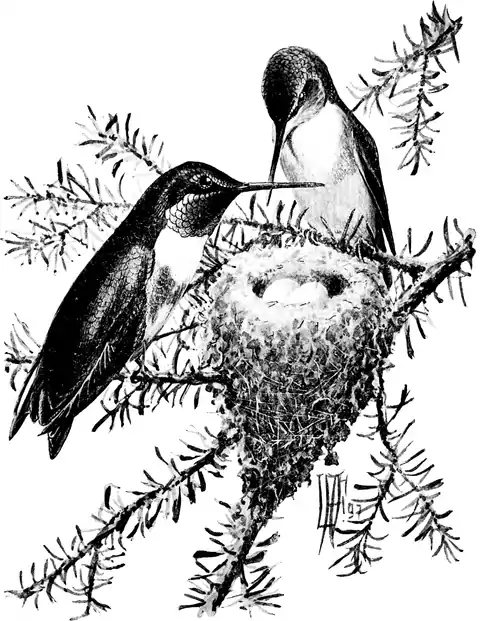

Plate 2.

Ruby-throated Hummingbird.

Length, 3.75 inches.

(See page 194.)

Ruby-throated Hummingbird:

Plate 2.

- Length:

- 3.76 inches.

- Male:

- Above metallic green; belly white. Wings and tail ruddy black, the latter deeply forked. Glistening ruby-red gorget.

- Female:

- Colours less iridescent; gorget lacking, tail with rounded points.

- Note:

- A shrill, mouse-like squeak.

- Season:

- Common summer resident; May to October.

- Breeds:

- From Florida to Labrador.

- Nest:

- A dainty circle an inch and a half in diameter, made of fern-wool, plant-down, etc., shingled with lichens to match the colour of the branch on which it is saddled.

- Eggs:

- 2, pure white, the size of soup-beans.

- Range:

- Eastern North America to the Plains, north to the Fur Countries, and south, in winter, to Cuba. and Veragua.

This is the only native Hummingbird of eastern North America, and it is impossible to confuse it with any other bird in its range.

When the late tulips and narcissi are blooming in the garden, and you hear a tense humming near them, varied by an occasional squeak, you know, Without looking, that the Hummingbirds have come. All through late May they dart here and there, now among the flowers, and then disappearing high up in the trees, searching for both honey and aphides with their proboscis-like tongues, while their movements exceed in dash and rapidity even the Swallows and Swifts. They seem merely to will to be in a certain spot, and they are there without efiort.

With June they settle in or near the garden, where the roses and honeysuckle supply them with nectar and ambrosia, and this is the season to study them. Late afternoon, between six and seven o’clock, is the best hour, for they are taking their supper, and the sun being low behind the trellis its rays shoot sidewise and bring out all the metallic splendour of their plumage. The adult birds seldom perch, but, drawing up their tiny claws, pause in front of the chosen flower, apparently motionless. But the hum of the wings tells the secret of the poise.

The parents jam their bills far down into the little gaping mouths, placing the food in the throat itself,—an effective but barbarous looking operation.

The nest is worthy of the bird, but is rare in comparison with the number of birds that are seen every year. There are two reasons for this; it blends so perfectly with the supporting branch as to be invisible when the leaves are on the trees, and owing to its spongy composition, it seldom retains its shape for any length of time.

Various nesting-sites are chosen, and in the garden I have found them, in different seasons, on a horizontal cedar bough, a slanting beech branch, a sweeping elm branch over the road, and one, which I discovered from a tower window, on the topmost branch of a spruce some sixty feet from the ground. In this last case the nest was covered with small flakes of spruce bark, instead of the usual lichens.

After the nesting the males make themselves exceedingly scarce, while the females and young haunt the garden, feeding in flocks, the young being distinguishable by their dullness of plumage and the fact that they perch frequently. All through August and early September, before cooling nights warn them away, they dart through the mellow haze claiming the last Jacque roses and the blossoms that continue to wreathe the honeysuckle, only leaving them when the twilight chill stiffens their feathered mechanism.

When the mild gold stars flower out,

As the summer gleaming goes,

A dim shape quivers about

Some sweet rich heart of a rose.

* * * * * * *

Then you, by thoughts of it stirred,

Still dreamily question them:

“Is it a gem, half bird,