As of Old

BY GEORGE WESTON

SPEAKING in a most significant voice, I wish to say that Mortimer had an appointment that afternoon to take Miss Josephine a spin in The Hornet, his forty-horse-power car. And (in a tone that fairly drips with unction) I will add that Mortimer made the following mechanical provisions to insure the proper running of the car—viz., he shaved himself for the second time that day, anointed his head with an exquisite eau de cologne, delicately dusted his brick-red features with talcum powder, and changed his necktie four times. Thus equipped and accoutred, he climbed into The Hornet, kicked at the clutch, and madly chug-a-chug-chugged to the house where Josephine was staying with her aunt. For though The Hornet had been his only love for eighteen months, Miss Josephine had come between them at last and had weaned his affections away.

She came smilingly, trippingly down the steps of her aunt's house (Miss Josephine did), while The Hornet rumbled and buzzed, and Mortimer tenderly helped her into the car and off they rode toward sylvan solitudes. She was silent because she was aware of the impropriety of distracting a driver's attention; and he was silent because of the vasty convolutions of his thoughts.

"I will ask her," he thought at last, drawing an equally vasty breath, "as soon as we come to the cross-roads." And while they drew near to the spot (appropriately marked as though with a highway X), he frowned like a general on the point of uttering an historic order; but when they came to the fateful place his perturbation was such that The Hornet nearly ran into the fence (to sting it, as one might say), and by the time he had regained the middle of the road the sign-post at the Corners was far behind them. He shot a glance toward the girl by his side and saw that she was as cool and as pensive as a Minerva modeled in snow.

"This," thought Mortimer. "is going to be hard." And, being something of a classical scholar, he added, "Eheu!"

On and on buzzed The Hornet, jealously requiring the use of both Mortimer's hands (to say nothing of his eyes and his feet), for the road was rough with ruts, and, though he had a very particular message to deliver to Josephine, he did not wish to impart it while they were catapulting through the air (like shooting-stars) or crashing into a stone wall (like meteors) or anything of that tempestuous sort. "All the same," he thought, "I will ask her when we come to the bridge." They reached the bridge, and while they were rumbling over it Mortimer bit his tongue and gently said:

"Miss Josephine—"

Apparently she did not hear him, so pensive was she.

"Miss Josephine—" he said, in a louder voice.

But still she pensively gazed at the great eternal hills.

"Miss Josephine!" he shouted.

But while she was turning her head to look at him The Hornet viciously struck a bunker that nearly sent them skidding into a grand old oak-tree which flourished by the side of the road. "This," thought Mortimer (with both hands on the wheel eyes on the road)—"this is like trying to eat with the hands tied. I would put it off if she wasn't going home to-night. For two cents I would stop the car and ask her, but it looks so crazy."

And no generous soul being there to offer him the mere pittance which he mentioned, and having, moreover, a deep-seated prejudice against a reputation for lunacy, they traveled on, and The Hornet hummed pleasantly under its hood and behaved altogether like a car that was having the time of its sportive young life.

"I'm awfully sorry that you're going away, Miss Josephine," said Mortimer. But he had to speak in a raucous and unromantic voice (so that she could hear him), and while he spoke he had to watch the road ahead for boulders.

"I'm sorry, too," she said; "I've had a lovely time."

"Before you leave—" he began, and then he stopped because a skittish horse attached to a surrey turned suddenly out from one of the side lanes (like a new figure in a nightmare) and reared up and gracefully and commandingly waved its forelegs at The Hornet as though inviting Mortimer to come and join it in the mazes of a mad, delirious waltz.

"What were you going to say, Mr. Perkins?" asked Miss Josephine, after the Terpsichorean horse had passed them, biped and unappeased.

"Oh yes," said Mortimer (in a now-or-never voice), "I was going to say that before you went back home I had a question I wanted—"

They were bowling down a steep hill leading to a village below, and a group of children were also riding down the hill in home-made coasters on wheels. The steepness of the hill and the hazard of the children kept Mortimer so fully occupied in restraining the homicidal possibilities of The Hornet that again he was obliged to leave his remark unfinished. But when he approached the foot of the hill and saw a livery-stable sign creaking gently in the breeze, an inspiration grand and noble dashed quickly through his comprehending mind.

"I know what I'll do," he smiled to himself. And when he came to the livery-stable The Hornet crawled along more and more slowly and then stopped dead in its tracks.

"Dear me!" exclaimed Mortimer, in a tone which was meant to indicate astonishment, "something is wrong!"

He jumped out, and, lifting the hood, he looked so wise that if he had been possessed of a beard, a short nose, and a different set of features he would have looked amazingly like Socrates.

"I'm afraid," he said to Josephine (and this time he wagged his head), "that we shall have to go home in a buggy."

And just at that psychological moment (if a moment can ever be called psychological) a loud voice shouted: "Hello, Mortimer! In trouble, old man?"

Mortimer turned around and gazed into the smiling countenance of Willis Andrews, and the more he gazed the more he hated him. For Willis was not only the most irritatingly handsome man in all those parts, he was not only a recognized diagnostician regarding the complaints of motor-cars, but he was also an ardent suitor for the hand of the pensive Josephine. Wherefore Mortimer hated him with a hatred more bitter than henbane, more enduring than granite and steel.

They had the carburetor apart in less time than it takes to verify the spelling of the word, and then they started after the spark-plug.

"Ah-ha!" cried Willis, with an aggravating accent of superior knowledge and beauty, "here's the trouble! One of the binding-posts is gone!"

"Well, well," muttered Mortimer (and he didn't look so very much like Socrates then). "Well, well."

"What a funny name!" exclaimed Miss Josephine, looking down from her place in the car. "What does it look like. Mr. Andrews?"

"It's about an inch long," he explained, "and as big around as a lead-pencil." he began looking around in the dust underneath the car, and he only gave up the search (and then with evident regret) when Josephine took her place in the buggy which Mortimer had hurriedly—almost feverishly—hired. "Push the car into the stable!" cried Mortimer to the breathless liverymen; "I'll be back to-morrow. Get up, Dobbin! Good-by, Willis!"

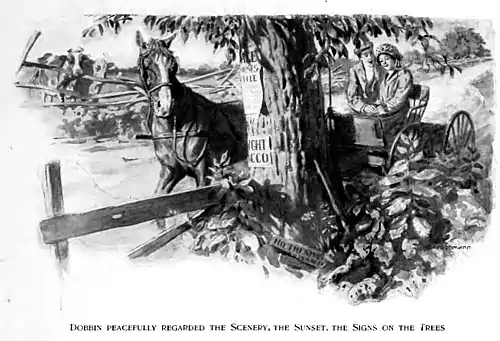

The twilight was falling and their homeward way was toward the setting sun. In front of them Dobbin jogged peacefully and rhythmically along, with the comfortable and reassuring appearance of a horse who could jog along peacefully forever. He peacefully regarded the cows, the scenery, the sunset, the signs on the trees, and yet he had (between his ears) a certain wise and knowledgable look which is extremely hard to define, though it may best be described as one of discreet expectancy.

"Josephine," said Mortimer, his arm stealing behind her (as it couldn't—in the car), "I meant to ask you before, but I couldn't (in the car). How would you like to be Mrs. Perkins?"

Slowly and shyly she nestled against him (as she couldn't—in the car), and when (a few moments later) she gave him her hand (to squeeze, I think—an operation quite impossible in the car) the missing binding-post fell coyly into his palm.

"Hello!" cried Mortimer, bending over and looking at it as though it fascinated him, "where did this come from?"

It might have been the sunset, or it might have been that she blushed for herself, or it might have been that she only blushed for him.

"When you were leaning over the machine and threw this behind you," she said, with great severity of manner, "you should have looked where it went, Mortimer."

"Where did it go?" he humbly asked.

"It landed in my lap," she said, more severely than before, "and thinking that you didn't want it—in the car—I hid it in my glove!"

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1968, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 50 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.