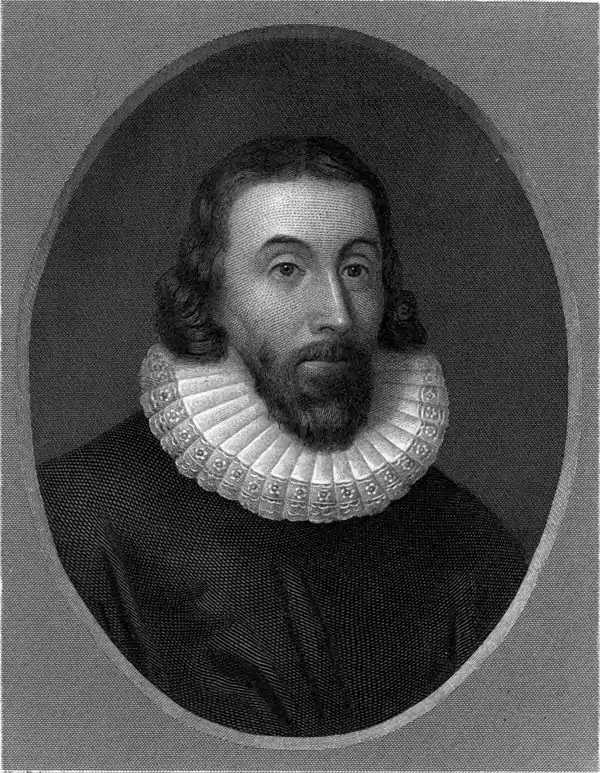

WINTHROP, John, governor of Massachusetts, b. in Edwardston, near Groton, Suffolk, England, 22 Jan., 1588; d. in Boston, Mass., 26 March, 1649. The manor of Groton had been purchased in 1544 by his grandfather, Adam Winthrop, a rich clothier of Suffolk, who had also a city home in St. Michael's, Cornhill, and who was for several years master of the famous Cloth-workers' company of London. A portrait of him, ascribed to Hans Holbein, indicates a man of culture, decision, and great strength of character. One of his daughters became the wife of Sir Thomas Mildmay, nephew of the founder of Emmanuel college; and another was the mother of Dr. William Alabaster, who is styled, in “Fuller's Worthies,” “a most rare poet as any our age or nation has produced: witnesse his Tragedy of Roxana.” Of this Adam Winthrop the third son, also named Adam, was a lawyer by profession, a graduate of Magdalen college, Cambridge, and for many years the auditor of Trinity and St. John's colleges. His first wife was a sister of Dr. John Still, bishop of Bath and Wells, but she died early without offspring. His second wife was Anne Browne, of Edwardston, and of this marriage John Winthrop, the subject of this notice, was the only son. His parents lived until within a few years of his coming to this country, his mother dying only one year before he embarked. Of the school or schools which he attended as a boy there is no record, but we find him admitted to Trinity college, Cambridge, on 18 Dec., 1602, when he was not quite fourteen years of age, and he remained there for more than two years. But his college life was brought prematurely to a close, before he was entitled to a degree, by his early engagement and marriage. On 26 April, 1605, he married Mary Forth, daughter and sole heir of John Forth, of Great Stambridge, in Essex. She was of a wealthy family, one of whom was knighted in 1604, and is said to have brought to her husband “a large portion of outward estate.” It is matter of tradition that he was made a justice of the peace on arriving at eighteen years of age, and that “he was exemplary for his grave and Christian deportment.” As early as 1609, when he had just attained his majority, he is recorded in his father's diary as holding “his first court in Groton Hall.” The wife of his youth was taken away within eleven years after their marriage, having borne him six children, of whom two had died in their earliest infancy; and a second wife, of the old Clopton family, had been buried, with her infant, only a year and a day after wedlock. He was sorely oppressed by such successive bereavements, and found consolation only in a more earnest cultivation of the Christian hope and faith which he had cherished from his childhood. There is reason for thinking that he had contemplated becoming a clergyman at this period, and his “Experiences,” as written at the

| |

| Van Dyke | Girsch |

to religious impressions, not without a tinge of superstition. But he gradually gave himself up to the profession of his father, engaged actively in the practice of the law and in the discharge of his duties as a magistrate, and in 1626 was appointed by Sir Robert Naunton one of the attorneys in the court of wards and liveries, over which Sir Robert presided. His professional services brought him also into connection with the parliamentary proceedings of the time, in preparing bills for legislative committees; and as late as 1628 we find record of his special admission to the Inner Temple, of which his eldest son had been admitted a member four years previously. Meantime he was once more established in domestic life, having married in 1618 Margaret, daughter of Sir John Tyndal, knight, of Great Maplested, in Essex, who was happily spared to him for nearly thirty years, and who was to be his companion and support for seventeen of those years in the New World.

The coming over of John Winthrop to America seems not to have been the result of any long previous deliberation. The earliest intimation of such a step is found in a letter dated 15 May, 1629, in which he says: “My dear wife, I am veryly persuaded God will bringe some heavye Affliction upon this lande, and that speedylye: but be of good comfort, the hardest that can come shall be a meanes to mortifie this bodye of corruption, which is a thousand tymes more dangerous to us than any outward tribulation, and to bring us into nearer communion with our Lord Jesus Christ, and more assurance of his kingdome. If the Lord seeth it will be good for us, he will provide a shelter and a hidinge place for us and others, as a Zoar for Lott, Sarephtah for his prophet,” etc. At this moment he was privately preparing a careful statement of the “Reasons to be considered for justefieing the undertakeres of the intended Plantation in New England, and for incouraginge such whose hartes God shall move to joyne with them in it.” This is the paper that he communicated for consideration to his eldest son (afterward governor of Connecticut) in August of the same year, and which elicited from him the memorable response: “For the business of New England I can say no other thing but that I believe confidently that the whole disposition thereof is of the Lord, who disposeth all alterations by his blessed will, to his own glory and the good of his; and therefore do assure myself that all things shall work together for the best therein. . . . The Conclusions which you sent down I showed my uncle and aunt, who liked them well. I think they are unanswerable.” In less than a year from the date of that letter John Winthrop, the father, was established in New England, having been elected governor of Massachusetts by the company in London, on 30 Oct., 1629, and having arrived at Salem, with the charter and company, in a fleet of eleven ships, of which the “Arbella” was “the admiral,” on 22 June, 1630. A few days later he went to what is now called Charlestown, and soon afterward to the site and settlement of Boston.

|

Both the religious and the political condition of Old England at that period were repulsive to minds like those of Winthrop and his associates. The king was systematically assuming and asserting despotic authority, and reducing the power of parliament to a nullity. Indeed, from March, 1629, no parliament was convoked for eleven years. It was the period of high commission, star chamber, tonnage and poundage, forced loans, and taxation without representation. Not a few distinguished men who opposed such a policy and resisted such exactions were seized and imprisoned. Sir John Eliot, to whom Winthrop was no stranger, was sent to the Tower for free speech in parliament, to die there after several years of suffering. The Puritan spirit, with which Winthrop strongly sympathized, was sternly repressed. Laud, as bishop of London, was already manifesting the bigoted and proscriptive policy which he displayed a few years later as archbishop of Canterbury, and which at last brought him to the block. Meantime the New World was open to freedom, and the little pioneer Pilgrim band was already sending over tidings of religious liberty from Plymouth Rock. All this will sufficiently explain the great Suffolk emigration, of which Winthrop was the chosen leader. The Massachusetts company had already established a plantation at Salem, and John Endicott had been deputed by them to govern the little colony in subordination to the governor and company in London. But they now solemnly resolved to transfer the whole government to the American soil, and Winthrop was made the leader and governor to effect and carry out that transfer, the company “having received, as the record says, extraordinary great commendations of his integrity and sufficiency.” Nineteen years intervened between the arrival of Gov. Winthrop at Salem and his death in Boston in 1649, during twelve of which he was the governor of the colony, and during every year of which he was actively engaged in its affairs. He was annually elected governor till 1634, and held the office again in 1637-'40, 1642-'4, and from 1646 till his death. In 1636, when Sir Harry Vane was chosen governor, Winthrop was deputy, and he led the opposition to Vane in the Anne Hutchinson controversy, on which issue he was elected over Vane in 1637. He was an earnest opponent of the new Antinomian doctrines, and was active in the banishment of Mrs. Hutchinson and her followers. In 1644-'5 he was again deputy governor. During that year he was virtually impeached, but his acquittal and the speech which followed it, with his celebrated definition of liberty, are among his most memorable triumphs. Winthrop lived to see Boston, which he had founded, a thriving and prosperous capital; and the state, of which he brought over the charter, extended by successive settlements over a wide territory, and represented, in its little legislature, by deputies from nearly thirty separate towns. Other colonies had planted themselves around Massachusetts, and a New England confederation had been formed under his auspices, of which he was the first president. Free schools had been established, and a college incorporated and organized. Above all, religion had taken deep root in all the settlements, and churches were gathered wherever there was an adequate population. Although he was a member of the Church of England as long as he resided in the mother country, and had united in an affectionate farewell to that church on his departure, he was a man who held Christianity to be above all churches. He soon saw clearly that Congregationalism was the best and only mode of planting and propagating Christianity in this part of the country and in those old Puritan times, and he was henceforth a Congregationalist until his death. Bancroft says of him: “It was principally the calm decision of Winthrop which sustained the courage of his companions.” Palfrey concludes a notice of him, in his “History of New England,” as follows: “Certain it is that, among the millions of living men descended from those whom he ruled, there is not one who does not, through efficient influences, transmitted in society and in thought along the intervening generations, owe much of what is best within him and in the circumstances about him to the benevolent and courageous wisdom of John Winthrop.”

He kept a careful journal of all that was done by himself and others, which he designed to have revised and perfected at his leisure; but no leisure ever came to him. The first volume was published from family manuscripts (Hartford, 1790). The continuation was discovered in 1816 in the tower of the Old South church in Boston, and placed in the hands of James Savage, who published the whole journal as “The History of New England from 1630 to 1649, by John Winthrop,” with notes (2 vols., Boston, 1825-'6; 2d ed., with additions, 1853). It furnishes the most authentic record of the early days of Massachusetts. Among other writings is an essay entitled “Arbitrary Government described; and the Government of the Massachusetts vindicated from that Aspersion.” It was written by him in 1644, but it saw the light only in 1869. His “Modell of Christian Charity,” written on board the “Arbella,” on his way to this country, is printed in the “Massachusetts Historical Collections.” His “Life and Letters” were published by Robert C. Winthrop (2 vols., Boston. 1864-'7). There is a portrait of him, ascribed to Vandyck, in the senate-chamber of Massachusetts, and reproduced in the accompanying steel engraving; a statue by Richard Greenough in the U. S. capitol at Washington, another in Boston and one in the chapel at Mount Auburn cemetery, seen in the illustration on page 573. —

|

His eldest son, John, known as John Winthrop the younger, b. in Groton Manor, 12 Feb., 1606; d. in Boston, Mass., 5 April, 1676, after being educated at Bury St. Edmunds school and Trinity college, Dublin, entered the Inner Temple, but, finding the study of law little to his taste, obtained temporary employment in the naval service and sailed under the Duke of Buckingham in the unfortunate expedition for the relief of the Protestants of Rochelle. A little later he made a prolonged tour of Europe, passed some time in Padua, Venice, and Constantinople, returning home in 1629, to find his friends busy with the great Massachusetts enterprise, in which he was soon actively enlisted. In 1631 he followed his father to New England, and he was shortly afterward elected an assistant of the Massachusetts colony, which post he retained for eighteen successive years. In 1633 he took the chief part in the settlement of Ipswich, Mass., where he acquired a considerable estate. In 1634 he went to England on public business, and he returned, in 1635, with a commission from Lords Say, Brooke, and others, empowering him to build a fort at the mouth of Connecticut river, and constituting him governor of that region for one year from his arrival. At the expiration of this term he preferred to return to Massachusetts, where he busied himself in scientific researches, in trying to develop the mineral resources of the colony, and in building salt-works. The journal of Gov. Winthrop the elder speaks of his son John at this period as possessing in Boston a library of more than 1,000 volumes, several hundred of which are still preserved, and bear testimony to the learning and broad intellectual tastes of their original owner. In 1640 he obtained a grant of Fisher's island, which was subsequently confirmed by royal patent. In 1641 he went again to England on a long absence, bringing back with him, in 1643, workmen and machinery with which he established iron-works at Lynn and Braintree. In 1646 he began the plantation at Pequot, better known as New London, and, having gradually acquired much landed property in that neighborhood, he transferred thither his principal residence in 1650, exchanging the duties of a Massachusetts for those of a Connecticut magistrate. In 1657 he was elected governor of Connecticut, and, with a single year's exception, he held that office till his death, nineteen years later. From the autumn of 1661 till the spring of 1663 he was chiefly in London on business of the colony, where he became widely known as an accomplished scholar, one of the earliest and most active members of the Royal society, and the personal friend of many of the chief natural philosophers of Europe, his correspondence with whom is in print. The ability and tact that he displayed at the court of Charles II. resulted in his obtaining from that monarch a charter uniting the colonies of Connecticut and New Haven, with the most ample privileges, under which the freemen of that colony became entitled to all the rights and immunities of Englishmen. In this charter Winthrop was named first governor, and in the administration of it he passed his remaining years. His death occurred in Boston, where he had gone to attend a meeting of the commissioners of the united colonies and where he was buried in his father's tomb. He had not the latter's heroic cast of character, and his tastes were rather those of a student than a statesman; but he was a man of singularly winning qualities and great moderation, whose Puritanism was devoid of bigotry or asceticism, and who knew how to retain the esteem of those from whom he differed most widely in opinion. By Indians he was revered for his justice, and by Quakers gratefully remembered for his lenity. In chemistry and medicine he was particularly skilled, and in the dearth of medical practitioners in the colony his advice was sought far and wide. He married, in 1631, his cousin Martha, daughter of Thomas Fones, of London, and step-daughter of Rev. Henry Painter; she died in Ipswich, without surviving issue, in 1634. He married, in 1635, Elizabeth, daughter of Edmund Reade, of Wickford in Essex, and step-daughter of the famous Hugh Peters; this lady, so lovingly alluded to in the letters of Roger Williams, died in Hartford in 1672, leaving two sons and five daughters. Much of the correspondence of her husband and sons is printed in the publications of the Massachusetts historical society. — The second John's elder son, John, known as Fitz-John, b. in Ipswich, Mass., 19 March, 1639; d. in Boston, Mass., 27 Nov., 1707, left Harvard without taking a degree in order to accept a commission in the parliamentary army, in which his father's brother, Stephen, and his mother's brother, Thomas Reade, were colonels. After seeing active service in Scotland, where he was for some time in command at Cardross, he accompanied Gen. George Monk on his famous march to London; but his regiment was disbanded at the Restoration, and he returned to New England in 1663, and passed the remainder of his life in the military and civil employment of Connecticut. He served with distinction in the Indian wars, sat in the council of Sir Edmund Andros, and was appointed in 1690 major-general commanding the joint expedition against Canada. The lukewarm support of the New York government and the bad faith of its Indian allies made this campaign a failure, but Fitz-John received a vote of thanks from Connecticut, and in 1693 was made agent of that colony in London, where he passed four years at the court of William III. His services in this capacity were so highly appreciated that, soon after his return in 1698, he was elected governor of Connecticut, continuing in office till his death nearly ten years later, while on a visit to his brother in Boston. His own principal residence was at New London, where he was noted for his hospitality. He was neither a great scholar like his father, nor a great statesman like his grandfather, but he was deservedly respected as a gallant soldier, a skilful administrator, and a man of conspicuous integrity and patriotism. He married, somewhat late in life, Elizabeth, daughter of George Tongue, of New London, and left an only child, Mary, who married Col. John Livingston, of Albany, but died without issue. — Another son of the second John, Wait Still, jurist, b. in Boston, 27 Feb., 1643; d. there, 7 Nov., 1717, was early in the military service of Connecticut, and took part in Indian wars; but after his father's death he resided chiefly in Massachusetts, where he was for about thirty years a member of the executive council and major-general of the provincial forces, besides holding, for shorter periods, the offices of judge of admiralty, judge of the superior court, and chief justice. He took an active part in the overthrow of Sir Edmund Andros, and an effort was made by the popular party to have him appointed governor, in place of Joseph Dudley. Judge Sewall speaks of him as “the great stay and ornament of the council, a very pious, prudent, courageous New England man; for parentage, piety, prudence, philosophy, love to New England ways and people very eminent.” In the intervals of public duty he devoted himself to agriculture and the study of medicine, often practising gratuitously among his neighbors. — Wait Still's son, John (1681-1747), was graduated at Harvard in 1700, served for some time as a magistrate of Connecticut, and was afterward a fellow of the Royal society of London, to whose “Transactions” he was a contributor, and one of whose volumes was dedicated to him. — John, physicist, b. in Boston, Mass., 19 Dec., 1714: d. in Cambridge, Mass., 3 May, 1779, was the son of Chief-Justice Adam Winthrop. He was graduated at Harvard in 1732, and from 1738 till his death was professor of mathematics and natural philosophy there. The range of his acquirements was great, and he did good original work in several departments of science. It seems likely that we owe in part to his influence the attention of Benjamin Franklin and of Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, to physical science. He was in the 18th century the foremost teacher of science in this country. In 1740 he observed the first of the transits of Mercury that took place in that century. In 1761 he observed the second transit, making a journey to Newfoundland for this purpose. The voyage was made in a vessel in the provincial service and the expenses were defrayed by the colonial government. This is believed to have been the earliest purely scientific expedition sent out by any American state. In the development of astronomy Prof. Winthrop made other important observations in the matter of comets, the results of which were published by means of two printed lectures (1759). He had an opportunity to observe the facts connected with the great earthquake that occurred in New England on 18 Nov., 1755. It was his habit to publish the more popular and interesting parts of his work in public lectures in the college chapel. His observations on this phenomenon were contained in a discourse printed in Boston within a month after the catastrophe. The observations recorded in this memoir and the scientific considerations that he based on them show that Winthrop had a clearer conception of earthquake movements than any of his predecessors. He recognized the fact that the movement was essentially a wave in the earth's crust, and perceived that the buildings affected by the shock took on a pendulum movement. Observing that the bricks were thrown from the chimney of his house, which had a height of thirty-two feet, so that they fell at a point thirty feet from the column, he com- puted the speed of their motion, and ascertained it to be twenty-one feet a second. He also perceived the fact that the shorter the vibrations the quicker they performed the movement. He saw also the analogy between the vibrations of the earth and those of the chord of a musical instrument. In this and many other observations he showed a capacity for observation and for the application of computative methods to this class of phenomena that was unusual in the scientists of his time. It appears probable that he was the first person to apply computations to earthquake phenomena. If this be the case, it may be claimed for him that he laid the foundations of the important science of seismology. Prof. Joseph Levering, in his account of “Boston and Science” in the “Memorial History of Boston,” says that “Prof. Winthrop's views of the nature of heat were greatly in advance of the science of his day.” We find in his lecture on earthquakes that he looked to the action of heat for an explanation of seismic disturbances. He had a considerable share in the public life of the colony where he lived. He was several years judge of probate for Middlesex county, a member of the governor's council in 1773-'4, and in the Revolution threw his influence with the patriots. The University of Edinburgh gave him the honorary degree of LL. D. in 1771, and the Royal society of London made him a member. Although Prof. Winthrop has left no work of any importance to modern physicists, his influence in determining a scientific spirit in New England was great. He laid the foundations of scientific inquiry in Harvard. Though not the earliest of the Massachusetts men of science — for he was preceded by Thomas Brattle, Zabdiel Boylston, and others — he deserves the first place among the pioneers of natural science in New England. His publications include “Lecture on Earthquakes” (1755); “Answer to Mr. Prince's Letter on Earthquakes” (1756); “Account of some Fiery Meteors” (1765); and “Two Lectures on the Parallax” (1769). His paper “Cogitata de Cometes” was communicated to the Royal society by Benjamin Franklin (London, 1766). — Prof. Winthrop's son, James, jurist, b. in Cambridge, Mass., in 1752; d. there, 26 Sept., 1821, was graduated at Harvard in 1769, and was wounded at Bunker Hill. He was librarian of Harvard from 1772 till 1787; for several years a judge of the court of common pleas; and long register of probate. He bequeathed his valuable library to Alleghany college, Meadville, Pa. He published “Attempt to translate the Prophetic Part of the Apocalypse of St. John into Familiar Language” (Boston, 1794); “Systematic Arrangement of Several Scripture Prophecies relating to Antichrist” (1795); “Attempt to arrange, in the Order of Time, Scripture Prophecies yet to be Fulfilled” (Cambridge, 1803); and scientific and literary contributions to current literature. — John Winthrop the younger's great-grandson, Thomas Lindall, merchant, b. in New London, Conn., 6 March, 1760; d. in Boston, Mass., 22 Feb., 1841, was graduated at Harvard in 1780, and in 1786 married Elizabeth Bowdoin Temple, a granddaughter of Gov. James Bowdoin and the daughter of Sir John Temple, British consul-general in the United States. In early life he was an active Federalist, but he joined the Republicans at the beginning of the war of 1812-'15, and was successively a state senator, lieutenant-governor of Massachusetts in 1826-'32, and a presidential elector. Few men of his time were so widely esteemed throughout New England for integrity, public spirit, and unostentatious hospitality. Among his many posts of public usefulness were those of president of the Massachusetts agricultural society, the Massachusetts historical society, and the American antiquarian society. —

|

|

Thomas Lindall's youngest son, Robert Charles, statesman, b. in Boston, 12 May, 1809, was graduated at Harvard in 1828, studied law with Daniel Webster, was admitted to the bar in 1831, but after a brief professional career became active in local politics as a Henry Clay Whig. From 1834 till 1840 he was a member of the lower house of the Massachusetts legislature, of which he was chosen speaker in 1838, 1839, and 1840. In the last-named year he was elected to congress, where he served ten years with much distinction, maintaining the reputation he had already acquired as a ready debater and accomplished parliamentarian, and adding to it by a series of impressive speeches upon public questions, many of which are still consulted as authorities. The earliest resolution in favor of international arbitration by a commission of civilians was offered by him. In 1847-'9 he was speaker of the house, but he was defeated for a second term by a plurality of two, after a contest that lasted three weeks. In 1850 he was appointed by the governor of Massachusetts to Daniel Webster's seat in the senate, when the latter became secretary of state. His course on the slavery question was often distasteful to men of extreme opinions in both sections of the Union, and in 1851 he was defeated for election to the senate by a coalition of Democrats and Free-soilers, after a struggle of six weeks. In the same year he was Whig candidate for governor of the state, and received a large plurality; but the constitution then required a majority, and the election was thrown into the legislature, where the same coalition defeated him. This occasioned a change in the state constitution, which now requires merely a plurality, but Mr. Winthrop declined to be a candidate again, and successively refused various other candidacies and appointments, preferring gradually to retire from political life and devote himself to literary, historical, and philanthropic occupations. From time to time, however, his voice was still heard in presidential elections, and he gave active and influential support to Gen. Winfield Scott in 1852, to Millard Fillmore in 1856, to John Bell in 1860, and to Gen. McClellan in 1864, when a speech of his at New London was the last, but not the least memorable, of his political addresses. Of the Boston provident association he was the laborious president for twenty-five years, of the Massachusetts historical society for thirty years, of the Alumni of Harvard for eight years, besides serving as chairman of the overseers of the poor of Boston, and in many other posts of dignity and usefulness. He was the chosen counsellor of George Peabody in several of his munificent benefactions, and has been from the outset at the head of the latter's important trust for southern education. It is as the favorite orator of great historical anniversaries that Mr. Winthrop has long been chiefly associated in the popular mind, and he has uniformly received the commendation of the best judges, not merely for the scholarship and finish of these productions, but for the manifestation in them of a fervid eloquence that the weight of years has failed to quench. They may be found scattered through four volumes of “Addresses and Speeches,” the first of which was published in 1852 and the last in 1886. Among the most admired of them have been an “Address on laying the Corner-Stone of the National Monument to Washington” in 1848, and one on the completion of that monument in 1885, the latter prepared at the request of congress; an “Address to the Alumni of Harvard,” in 1857; an “Oration on the 250th Anniversary of the Landing of the Pilgrims,” in 1870; the “Boston Centennial Oration,” 4 July, 1876; an address on unveiling the statue of Col. Prescott on Bunker Hill, in 1881; and, in the same year, an oration on the hundredth anniversary of the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown, delivered by invitation of congress. He has been thought equally to excel in shorter and less formal utterances. Several speeches of his on Boston common during the civil war excited much enthusiasm by their patriotic ring; while his brief tributes to John Quincy Adams, John C. Calhoun, Edward Everett, Daniel Webster, Abraham Lincoln, and many other eminent men with whom he had been associated at different periods, are models of graceful and discriminating eulogy. Besides the collected works already cited, he is the author of the “Life and Letters of John Winthrop” (2 vols., Boston, 1864), and “Washington, Bowdoin, and Franklin” (1876). A portrait of him, in the capitol at Washington, presented by citizens of Massachusetts, commemorates at once his speakership and his Yorktown oration; while another, in the hall of the Massachusetts historical society, is a fit reminder of his services to New England history. — Thomas Lindall's nephew, Benjamin Robert, capitalist, b. in New York city, 18 Jan., 1804; d. in London, England, 26 July, 1879, was in early life a clerk in the banking-house of Jacob Barker, but afterward devoted himself to the care of a large inherited estate and to furthering the interests of public institutions of education, charity, and religion in his native city. He was a trustee of the old Public school society, and on its dissolution in 1853 became a school commissioner and member of the board of education; was an earnest friend of the New York hospital, the Lying-in hospital, and other similar institutions; and by his care and liberality did much to advance the prosperity of the Institution for the deaf and dumb. He was recording secretary and vice-president of the New York historical society, and for many years a vestryman of Trinity church, as a member of whose cemetery committee he originated the plan of displaying plants in the church-yards of the parish. Among his publications is an address on “Old New York,” which he read before the Historical society (New York, 1862). —

|

|

The second John's descendant, Theodore, author, b. in New Haven, Conn., 22 Sept., 1828; d. near Great Bethel, Va., 10 June, 1861, was the son of Francis Bayard Winthrop. His mother was Elizabeth Woolsey, a niece of President Timothy Dwight, and sister of President Theodore Woolsey, for whom Theodore was named. He was graduated at Yale in 1848, with the Clark scholarship, on which he continued there a year, studying mental science, languages, and history. In 1849 he went to recruit his health in Europe, where he remained until January, 1851. There he became acquainted with William H. Aspinwall, whose children he taught for some time, and through him Winthrop entered the employ of the Pacific mail steamship company, to whose offices in Panama he was transferred in 1852. In the following year he visited California and Oregon, and thence he returned overland to New York. In December, 1853, he joined, as a volunteer, the expedition under Lieut. Isaac G. Strain to survey a canal-route across the Isthmus of Panama, and soon after his return in March, 1854, he began to study law with Charles Tracy. He was admitted to the bar in 1855, and in the following year, during a vacation-trip in Maine, made political speeches there in advocacy of John C. Frémont. After this he spent most of his time in literary pursuits, for which he had always had a fondness. The first of his writings that appeared in print was a description of his friend Frederic E. Church's painting, “The Heart of the Andes,” whose progress he had watched at the easel. For several years Winthrop worked carefully on his novels, recasting them after each rejection by a publisher. One, “Cecil Dreeme” was finally accepted, but the opening of the civil war delayed its appearance. Another, “John Brent,” was also accepted on condition that the author should omit the episode of the death of the horse Don Fulano. which he refused to do. At the opening of the civil war Winthrop enlisted in the 7th New York regiment, which he accompanied to Washington. Soon afterward he went with Gen. Benjamin F. Butler to Fort Monroe as military secretary, with the rank of major, and with his commanding officer he planned the attack on Little and Great Bethel, in which he took part. During the action at the latter place he sprang upon a log to rally his men, and received a bullet in his heart. Shortly before his departure for the seat of war his tale “Love and Skates” had been accepted for the “Atlantic Monthly” by its editor, James Russell Lowell, who then asked the author to furnish an account of his march to Washington for the magazine. This he did in two articles, which attracted much attention, and made Winthrop so well known that the sudden end of his career soon afterward occasioned wide-spread sorrow. Immediately after his death his novels appeared in quick succession, and were very favorably received. They have held their place in American literature, and it is probable that had Winthrop lived he would have taken high rank as a writer. Prof. John Nichol, of Glasgow, says of “Cecil Dreeme”: “With all its defects of irregular construction, this novel is marked by a more distinct vein of original genius than any American work of fiction known to us that has appeared since the author's death.” His books include the three novels “Cecil Dreeme” (Boston, October, 1861), “John Brent” (January, 1862), and “Edwin Brothertoft” (July, 1862); and the collections of sketches “The Canoe and the Saddle” (November, 1862), and “Life in the Open Air, and other Papers” (May, 1863). These have passed through many editions, and were reprinted in the “Leisure-Hour Series,” with the addition of his “Life and Poems,” edited by his sister, Laura Winthrop Johnson (New York, 1884). See also a memoir by George William Curtis, prefixed to the earlier editions of “Cecil Dreeme.” — Theodore's brother, William Woolsey, soldier, b. in New Haven, Conn., 3 Aug., 1831, was graduated at Yale in 1851, and at the law-school in 1853, and afterward continued his legal studies at Harvard. He was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1854, and practised until April, 1861, when he entered the 7th New York regiment as a private. He was commissioned 1st lieutenant of sharp-shooters, 1 Oct., 1861, became captain, 22 Sept., 1862, was made major and judge-advocate, 19 Sept., 1864, and at the close of the war brevetted colonel for meritorious service. On 25 Feb., 1867, he was commissioned major in the regular army, and on 5 July, 1884, he became lieutenant-colonel and deputy judge-advocate-general. He is now professor of law in the U. S. military academy. Col. Winthrop is the author of “Digest of Opinions of the Judge-Advocates-General of the Army” (Washington, 1865; enlarged eds., 1866 and 1868; greatly enlarged and annotated, 1880); and “Treatise on Military Law” (2 vols., 1886; condensed into one volume for the use of the cadets at the military academy as “Abridgment of Military Law,” 1887). He has also translated the “Military Penal Code of the German Empire” (1873). — Their sister, Laura, author, b. in New Haven, Conn., 13 Sept., 1825, was educated at private schools in her native place, and in 1846 married W. Templeton Johnson. Besides the above-mentioned “Life and Poems” of her brother Theodore, she has published “Little Blossom's Reward,” a book for children, under the pen-name of “Emily Hare” (Boston, 1854); “Poems of Twenty Years” (New York, 1874); a “Longfellow Prose Birth-day Book” (Boston, 1888); and various articles in magazines. — Theodore's cousin, Frederick, soldier, b. in New York city, 3 Aug., 1839; d. near Five Forks, Va., 1 April, 1865, was the son of Thomas C. Winthrop. He was commissioned a captain in the 12th U. S. infantry, 26 Oct., 1861, and received the brevet of brigadier-general of volunteers on 1 Aug., 1864. He was killed at the battle of Five Forks, where he commanded a brigade in the 5th corps. In 1867 the brevet of major-general of volunteers was conferred on him, among the few brevets that were given after death. It was dated back to 1 April, 1865, the day of the battle in which he fell.