V

The Episode of the Drawn Game

The twelfth of August saw us, as usual, at Seldon Castle, Ross-shire. It is part of Charles's restless, roving temperament that, on the morning of the eleventh, wet or fine, he must set out from London, whether the House is sitting or not, in defiance of the most urgent three-line whips; and at dawn on the twelfth he must be at work on his moors, shooting down the young birds with might and main, at the earliest possible legal moment.

He goes on like Saul, slaying his thousands, or, like David, his tens of thousands, with all the guns in the house to help him, till the keepers warn him he has killed as many grouse as they consider desirable; and then, having done his duty, as he thinks, in this respect, he retires precipitately with flying colours to Brighton, Nice, Monte Carlo, or elsewhere. He must be always 'on the trek'; when he is buried, I believe he will not be able to rest quiet in his grave: his ghost will walk the world to terrify old ladies.

'At Seldon, at least,' he said to me, with a sigh, as he stepped into his Pullman, 'I shall be safe from that impostor!'

And indeed, as soon as he had begun to tire a little of counting up his hundreds of brace per diem, he found a trifling piece of financial work cut ready to his hand, which amply distracted his mind for the moment from Colonel Clay, his accomplices, and his villainies.

Sir Charles, I ought to say, had secured during that summer a very advantageous option in a part of Africa on the Transvaal frontier, rumoured to be auriferous. Now, whether it was auriferous or not before, the mere fact that Charles had secured some claim on it naturally made it so; for no man had ever the genuine Midas-touch to a greater degree than Charles Vandrift: whatever he handles turns at once to gold, if not to diamonds. Therefore, as soon as my brother-in-law had obtained this option from the native vendor (a most respected chief, by name Montsioa), and promoted a company of his own to develop it, his great rival in that region, Lord Craig-Ellachie (formerly Sir David Alexander Granton), immediately secured a similar option of an adjacent track, the larger part of which had pretty much the same geological conditions as that covered by Sir Charles’s right of pre-emption.

We were not wholly disappointed, as it turned out, in the result. A month or two later, while we were still at Seldon, we received a long and encouraging letter from our prospectors on the spot, who had been hunting over the ground in search of gold-reefs. They reported that they had found a good auriferous vein in a corner of the tract, approachable by adit-levels; but, unfortunately, only a few yards of the lode lay within the limits of Sir Charles's area. The remainder ran on at once into what was locally known as Craig-Ellachie's section.

However, our prospectors had been canny, they said; though young Mr. Granton was prospecting at the same time, in the self-same ridge, not very far from them, his miners had failed to discover the auriferous quartz; so our men had held their tongues about it, wisely leaving it for Charles to govern himself accordingly.

'Can you dispute the boundary?' I asked.

'Impossible,' Charles answered. 'You see, the limit is a meridian of longitude. There's no getting over that. Can't pretend to deny it. No buying over the sun! No bribing the instruments! Besides, we drew the line ourselves. We've only one way out of it, Sey. Amalgamate! Amalgamate!'

Charles is a marvellous man! The very voice in which he murmured that blessed word 'Amalgamate!' was in itself a poem.

'Capital!' I answered. 'Say nothing about it, and join forces with Craig-Ellachie.'

Charles closed one eye pensively.

That very same evening came a telegram in cipher from our chief engineer on the territory of the option: 'Young Granton has somehow given us the slip and gone home. We suspect he knows all. But we have not divulged the secret to anybody.'

'Seymour,' my brother-in-law said impressively, 'there is no time to be lost. I must write this evening to Sir David—I mean to My Lord. Do you happen to know where he is stopping at present?'

'The Morning Post announced two or three days ago that he was at Glen-Ellachie,' I answered.

'Then I'll ask him to come over and thrash the matter out with me,' my brother-in-law went on. 'A very rich reef, they say. I must have my finger in it!'

We adjourned into the study, where Sir Charles drafted, I must admit, a most judicious letter to the rival capitalist. He pointed out that the mineral resources of the country were probably great, but as yet uncertain. That the expense of crushing and milling might be almost prohibitive. That access to fuel was costly, and its conveyance difficult. That water was scarce, and commanded by our section. That two rival companies, if they happened to hit upon ore, might cut one another's throats by erecting two sets of furnaces or pumping plants, and bringing two separate streams to the spot, where one would answer. In short—to employ the golden word—that amalgamation might prove better in the end than competition; and that he advised, at least, a conference on the subject.

I wrote it out fair for him, and Sir Charles, with the air of a Cromwell, signed it.

'This is important, Sey,' he said. 'It had better be registered, for fear of falling into improper hands. Don't give it to Dobson; let

Césarine took it as directed.Césarine take it over to Fowlis in the dog-cart.'

It is the drawback of Seldon that we are twelve miles from a railway station, though we look out on one of the loveliest firths in Scotland.

Césarine took it as directed—an invaluable servant, that girl! Meanwhile, we learned from the Morning Post next day that young Mr. Granton had stolen a march upon us. He had arrived from Africa by the same mail with our agent's letter, and had joined his father at once at Glen-Ellachie.

Two days later we received a most polite reply from the opposing interest. It ran after this fashion:—

'Craig-Ellachie Lodge,

'Glen-Ellachie, Inverness-shire.

'Dear Sir Charles Vandrift — Thanks for yours of the 20th. In reply, I can only say I fully reciprocate your amiable desire that nothing adverse to either of our companies should happen in South Africa. With regard to your suggestion that we should meet in person, to, discuss the basis of a possible amalgamation, I can only say my house is at present full of guests—as is doubtless your own—and I should therefore find it practically impossible to leave Glen-Ellachie. Fortunately, however, my son David is now at home on a brief holiday from Kimberley; and it will give him great pleasure to come over and hear what you have to say in favour of an arrangement which certainly, on some grounds, seems to me desirable in the interests of both our concessions alike. He will arrive to-morrow afternoon at Seldon, and he is authorised, in every respect, to negotiate with full powers on behalf of myself and the other directors. With kindest regards to your wife and sons, I remain, dear Sir Charles, yours faithfully,

'Craig-Ellachie.'

'Cunning old fox!' Sir Charles exclaimed, with a sniff. 'What's he up to now, I wonder? Seems almost as anxious to amalgamate as we ourselves are, Sey.' A sudden thought struck him. 'Do you know,' he cried, looking up, 'I really believe the same thing must have happened to both our exploring parties. They must have found a reef that goes under our ground, and the wicked old rascal wants to cheat us out of it!'

'As we want to cheat him,' I ventured to interpose.

Charles looked at me fixedly. 'Well, if so, we're both in luck,' he murmured, after a pause; 'though we can only get to know the whereabouts of their find by joining hands with them and showing them ours. Still, it's good business either way. But I shall be cautious—cautious.'

'What a nuisance!' Amelia cried, when we told her of the incident. 'I suppose I shall have to put the man up for the night—a nasty, raw-boned, half-baked Scotchman, you may be certain.'

On Wednesday afternoon, about three, young Granton arrived. He was a pleasant-featured, red-haired, sandy-whiskered youth, not unlike his father; but, strange to say, he dropped in to call, instead of bringing his luggage.

'Why, you're not going back to Glen-Ellachie to-night, surely?' Charles exclaimed, in amazement. 'Lady Vandrift will be so disappointed! Besides, this business can't be arranged between two trains, do you think, Mr. Granton?'

Young Granton smiled. He had an agreeable smile—canny, yet open.

'Oh no,' he said frankly. 'I didn't mean to go back. I've put up at the inn. I have my wife with me, you know—and, I wasn't invited.'

Amelia was of opinion, when we told her this episode, that David Granton wouldn't stop at Seldon because he was an Honourable. Isabel was of opinion he wouldn't stop because he had married an unpresentable young woman somewhere out in South Africa. Charles was of opinion that, as representative of the hostile interest, he put up at the inn, because it might tie his hands in some way to be the guest of the chairman of the rival company. And I was of opinion that he had heard of the castle, and knew it well by report as the dullest country-house to stay at in Scotland.

However that may be, young Granton insisted on remaining at the Cromarty Arms, though he told us his wife would be delighted to receive a call from Lady Vandrift and Mrs. Wentworth. So we all returned with him to bring the Honourable Mrs. Granton up to tea at the Castle.

She was a nice little thing, very shy and timid, but by no means unpresentable, and an evident lady. She giggled at the end of every sentence; and she was endowed with a slight squint, which somehow seemed to point all her feeble sallies. She knew little outside South Africa; but of that she talked prettily; and she won all our hearts, in spite of the cast in her eye, by her unaffected simplicity.

Next morning Charles and I had a regular debate with young Granton about the rival options. Our talk was of cyanide processes, reverberatories, pennyweights, water-jackets. But it dawned upon us soon that, in spite of his red hair and his innocent manners, our friend, the Honourable David Granton, knew a thing or two. Gradually and gracefully he let us see that Lord Craig-Ellachie had sent him for the benefit of the company, but that he had come for the benefit of the Honourable David Granton.

'I'm a younger son, Sir Charles,' he said; 'and therefore I have to feather my nest for myself. I know the ground. My father will be guided

She was endowed with a slight squint.implicitly by what I advise in the matter. We are men of the world. Now, let's be business-like. You want to amalgamate. You wouldn't do that, of course, if you didn't know of something to the advantage of my father's company—say, a lode on our land—which you hope to secure for yourself by amalgamation. Very well; I can make or mar your project. If you choose to render it worth my while, I'll induce my father and his directors to amalgamate. If you don't, I won't. That's the long and the short of it!'

Charles looked at him admiringly.

'Young man,' he said, 'you're deep, very deep—for your age. Is this candour—or deception? Do you mean what you say? Or do you know some reason why it suits your father's book to amalgamate as well as it suits mine? And are you trying to keep it from me?' He fingered his chin. 'If I only knew that,' he went on, 'I should know how to deal with you.'

Young Granton smiled again. 'You're a financier, Sir Charles,' he answered. 'I wonder, at your time of life, you should pause to ask another financier whether he's trying to fill his own pocket—or his father's. Whatever is my father's goes to his eldest son—and I am his youngest.'

'You are right as to general principles,' Sir Charles replied, quite affectionately. 'Most sound and sensible. But how do I know you haven't bargained already in the same way with your father? You may have settled with him, and be trying to diddle me.'

The young man assumed a most candid air. 'Look here,' he said, leaning forward. 'I offer you this chance. Take it or leave it. Do you wish to purchase my aid for this amalgamation by a moderate commission on the net value of my father's option to yourself—which I know approximately?'

'Say five per cent,' I suggested, in a tentative voice, just to justify my presence.

He looked me through and through. 'Ten is more usual,' he answered, in a peculiar tone and with a peculiar glance.

Great heavens, how I winced! I knew what his words meant. They were the very words I had said myself to Colonel Clay, as the Count von Lebenstein,

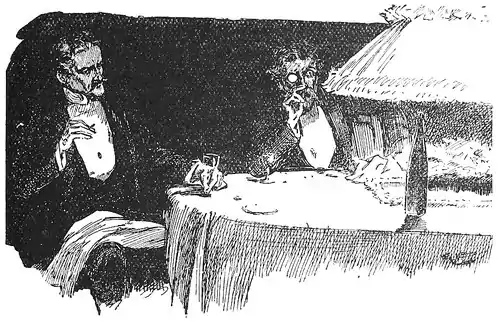

Ten is more usual.about the purchase-money of the schloss—and in the very same accent. I saw through it all now. That beastly cheque! This was Colonel Clay; and he was trying to buy up my silence and assistance by the threat of exposure!

My blood ran cold. I didn't know how to answer him. What happened at the rest of that interview I really couldn't tell you. My brain reeled round. I heard just faint echoes of 'fuel' and 'reduction works.' What on earth was I to do? If I told Charles my suspicion—for it was only a suspicion—the fellow might turn upon me and disclose the cheque, which would suffice to ruin me. If I didn't, I ran a risk of being considered by Charles an accomplice and a confederate.

The interview was long. I hardly know how I struggled through it. At the end young Granton went off, well satisfied, if it was young Granton; and Amelia invited him and his wife up to dinner at the castle.

Whatever else they were, they were capital company. They stopped for three days more at the Cromarty Arms. And Charles debated and discussed incessantly. He couldn’t quite make up his mind what to do in the affair; and I certainly couldn't help him. I never was placed in such a fix in my life. I did my best to preserve a strict neutrality.

Young Granton, it turned out, was a most agreeable person; and so, in her way, was that timid, unpretending South African wife of his. She was naïvely surprised Amelia had never met her mamma at Durban. They both talked delightfully, and had lots of good stories—mostly with points that told against the Craig-Ellachie people. Moreover, the Honourable David was a splendid swimmer. He went out in a boat with us, and dived like a seal. He was burning to teach Charles and myself to swim, when we told him we could neither of us take a single stroke; he said it was an accomplishment incumbent upon every true Englishman. But Charles hates the water; while, as for myself, I detest every known form of muscular exercise.

However, we consented that he should row us on the Firth, and made an appointment one day with himself and his wife for four the next evening.

That night Charles came to me with a very grave face in my own bedroom. 'Sey,' he said, under his breath, 'have you observed? Have you watched? Have you any suspicions?'

I trembled violently. I felt all was up. 'Suspicions of whom?' I asked. 'Not surely of Simpson?' (he was Sir Charles's valet).

My respected brother-in-law looked at me contemptuously.

'Sey,' he said, 'are you trying to take me in? No, not of Simpson: of these two young folks. My own belief is—they're Colonel Clay and Madame Picardet.'

'Impossible!' I cried.

He nodded. 'I'm sure of it.'

'How do you know?'

'Instinctively.'

I seized his arm. 'Charles,' I said, imploring him, 'do nothing rash. Remember how you exposed yourself to the ridicule of fools over Dr. Polperro!'

'I've thought of that,' he answered, 'and I mean to ca' caller.' (When in Scotland as laird of Seldon, Charles loves both to dress and to speak the part thoroughly.) 'First thing to-morrow I shall telegraph over to inquire at Glen-Ellachie; I shall find out whether this is really young Granton or not; meanwhile, I shall keep my eye close upon the fellow.'

A groom was dispatched with a telegram.

Early next morning, accordingly, a groom was dispatched with a telegram to Lord Craig-Ellachie. He was to ride over to Fowlis, send it off at once, and wait for the answer. At the same time, as it was probable Lord Craig-Ellachie would have started for the moors before the telegram reached the Lodge, I did not myself expect to see the reply arrive much before seven or eight that evening. Meanwhile, as it was far from certain we had not the real David Granton to deal with, it was necessary to be polite to our friendly rivals. Our experience in the Polperro incident had shown us both that too much zeal may be more dangerous than too little. Nevertheless, taught by previous misfortunes, we kept watching our man pretty close, determined that on this occasion, at least, he should neither do us nor yet escape us.

About four o'clock the red-haired young man and his pretty little wife came up to call for us. She looked so charming and squinted so enchantingly, one could hardly believe she was not as simple and innocent as she seemed to be. She tripped down to the Seldon boat-house, with Charles by her side, giggling and squinting her best, and then helped her husband to get the skiff ready. As she did so, Charles sidled up to me. 'Sey,' he whispered, 'I'm an old hand, and I'm not readily taken in. I've been talking to that girl, and upon my soul I think she’s all right. She's a charming little lady. We may be mistaken after all, of course, about young Granton. In any case, it's well for the present to be courteous. A most important option! If it's really he, we must do nothing to annoy him or let him see we suspect him.’

I had noticed, indeed, that Mrs. Granton had made herself most agreeable to Charles from the very beginning. And as to one thing he was right. In her timid, shrinking way she was undeniably charming. That cast in her eye was all pure piquancy.

We rowed out on to the Firth, or, to be more strictly correct, the two Grantons rowed while Charles and I sat and leaned back in the stern on the luxurious cushions. They rowed fast and well. In a very few minutes they had rounded the point and got clear out of sight of the Cockneyfied towers and false battlements of Seldon.

Mrs. Granton pulled stroke. Even as she rowed she kept up a brisk undercurrent of timid chaff with Sir Charles, giggling all the while, half forward, half shy, like a school-girl who flirts with a man old enough to be her grandfather.

Sir Charles was flattered. He is susceptible to the pleasures of female attention, especially from the young, the simple, and the innocent. The wiles of women of the world he knows too well; but a pretty little ingénue can twist him round her finger. They rowed on and on, till they drew abreast of Seamew's island. It is a jagged stack or skerry, well out to sea, very wild and precipitous on the landward side, but shelving gently outward; perhaps an acre in extent, with steep gray cliffs, covered at that time with crimson masses of red valerian. Mrs. Granton rowed up close to it. 'Oh, what lovely flowers!' she cried, throwing her head back and gazing at them. 'I wish I could get some! Let's land here and pick them. Sir Charles, you shall gather me a nice bunch for my sitting-room.'

Charles rose to it innocently, like a trout to a fly.

'By all means, my dear child, I—I have a passion for flowers;' which was a flower of speech itself, but it served its purpose.

They rowed us round to the far side, where is the easiest landing-place. It struck me as odd at the moment that they seemed to know it. Then young Granton jumped lightly ashore; Mrs. Granton skipped after him. I confess it made me feel rather ashamed to see how clumsily Charles and I followed them, treading gingerly on the thwarts for fear of upsetting the boat, while the artless young thing just flew over the gunwale. So like White Heather! However, we got ashore at last in safety, and began to climb the rocks as well as we were able in search of the valerian.

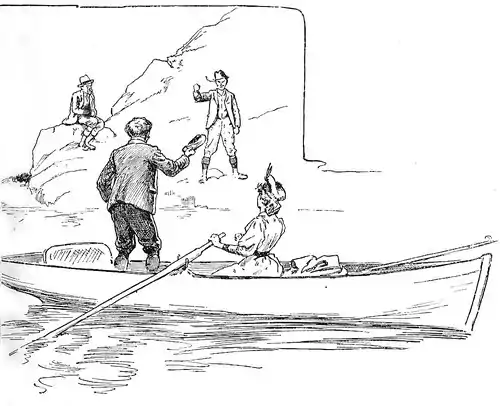

Judge of our astonishment when next moment those two young people bounded back into the boat, pushed off with a peal of merry laughter, and left us there staring at them!

They rowed away, about twenty yards, into deep water. Then the man turned, and waved his hand at us gracefully. 'Good-bye!' he said, 'good-bye! Hope you'll pick a nice bunch! We're off to London!'

'Off!' Charles exclaimed, turning pale. 'Off! What do you mean? You don't surely mean to say you're going to leave us here?'

The young man raised his cap with perfect politeness, while Mrs. Granton smiled, nodded, and kissed her pretty hand to us. 'Yes,' he answered; 'for the present. We retire from the game. The fact of it is, it's a trifle too thin: this is a coup manqué.'

'A what?' Charles exclaimed, perspiring visibly.

'A coup manqué,' the young man replied, with a compassionate smile. 'A failure, don't you know; a bad shot; a fiasco. I learn from my scouts that you sent a telegram by special messenger to Lord Craig-Ellachie this morning. That shows you suspect me. Now, it is a principle of my system never to go on for one move with a game when I find myself suspected. The slightest symptom of distrust, and—I back out immediately. My plans can only be worked to satisfaction when there is perfect confidence on the part of my patient. It is a well-known rule of the medical profession. I never try to bleed a man who struggles. So now we're off. Ta-ta! Good luck to you!'

He was not much more than twenty yards away, and could talk to us quite easily. But the water was deep; the islet rose sheer from I'm sure I don't know how many fathoms of sea; and we could neither of us swim. Charles stretched out his arms imploringly. 'For Heaven's sake,' he cried, 'don't tell me you really mean to leave us here.'

He looked so comical in his distress and terror that Mrs. Granton—Madame Picardet—whatever I am to call her—laughed melodiously in her prettiest way at the sight of him. 'Dear Sir Charles,' she called out, 'pray don't be afraid! It's only a short

Ta-ta!and temporary imprisonment. We will send men to take you off. Dear David and I only need just time enough to get well ashore and make—oh!—a few slight alterations in our personal appearance.' And she indicated with her hand, laughing, dear David's red wig and false sandy whiskers, as we felt convinced they must be now. She looked at them and tittered. Her manner at this moment was anything but shy. In fact, I will venture to say, it was that of a bold and brazen-faced hoyden.

'Then you are Colonel Clay!' Sir Charles cried, mopping his brow with his handkerchief.

'If you choose to call me so,' the young man answered politely. 'I'm sure it's most kind of you to supply me with a commission in Her Majesty's service. However, time presses, and we want to push off. Don't alarm yourselves unnecessarily. I will send a boat to take you away from this rock at the earliest possible moment consistent with my personal safety and my dear companion's.' He laid his hand on his heart and struck a sentimental attitude. 'I have received too many unwilling kindnesses at your hands, Sir Charles,' he continued, 'not to feel how wrong it would be of me to inconvenience you for nothing. Rest assured that you shall be rescued by midnight at latest. Fortunately, the weather just at present is warm, and I see no chance of rain; so you will suffer, if at all, from nothing worse than the pangs of temporary hunger.'

Mrs. Granton, no longer squinting—'twas a mere trick she had assumed—rose up in the boat and stretched out a rug to us. 'Catch!' she cried, in a merry voice, and flung it at us, doubled. It fell at our feet; she was a capital thrower.

'Now, you dear Sir Charles,' she went on, 'take that to keep you warm! You know I am really quite fond of you. You're not half a bad old boy when one takes you the right way. You have a human side to you. Why, I often wear that sweetly pretty brooch you gave me at Nice, when I was Madame Picardet! And I’m sure your goodness to me at Lucerne, when I was the little curate's wife, is a thing to remember. We're so glad to have seen you in your lovely Scotch home you were always so proud of! Don't be frightened, please. We wouldn't hurt you for worlds. We are so sorry we have to take this inhospitable means of evading you. But dear David—I must call him dear David still—instinctively felt that you were beginning to suspect us; and he can't bear mistrust. He is so sensitive! The moment people mistrust him, he must break off with them at once. This was the only way to get you both off our hands while we make the needful little arrangements to depart; and we've been driven to avail ourselves of it. However, I will give you my word of honour, as a lady, you shall be fetched away to-night. If dear David doesn't do it, why, I'll do it myself.' And she blew another kiss to us.

Charles was half beside himself, divided between alternate terror and anger. 'Oh, we shall die here!' he exclaimed. 'Nobody'd ever dream of coming to this rock to search for me.'

'What a pity you didn't let me teach you to swim!' Colonel Clay interposed. 'It is a noble exercise, and very useful indeed in such special emergencies! Well, ta-ta! I'm off! You nearly scored one this time; but, by putting you here for the moment, and keeping you till we’re gone, I

Charles was half beside himself.

venture to say I've redressed the board, and I think we may count it a drawn game, mayn't we? The match stands at three, love—with some thousands in pocket?'

'You're a murderer, sir!' Charles shrieked out. 'We shall starve or die here!'

Colonel Clay on his side was all sweet reasonableness. 'Now, my dear sir,' he expostulated, one hand held palm outward, 'do you think it probable I would kill the goose that lays the golden eggs, with so little compunction? No, no, Sir Charles Vandrift; I know too well how much you are worth to me. I return you on my income-tax paper as five thousand a year, clear profit of my profession. Suppose you were to die! I might be compelled to find some new and far less lucrative source of plunder. Your heirs, executors, or assignees might not suit my purpose. The fact of it is, sir, your temperament and mine are exactly adapted one to the other. I understand you; and you do not understand me—which is often the basis of the firmest friendships. I can catch you just where you are trying to catch other people. Your very smartness assists me; for I admit you are smart. As a regular financier, I allow, I couldn't hold a candle to you. But in my humbler walk of life I know just how to utilise you. I lead you on, where you think you are going to gain some advantage over others; and by dexterously playing upon your love of a good bargain, your innate desire to best somebody else—I succeed in besting you. There, sir, you have the philosophy of our mutual relations.'

He bowed and raised his cap. Charles looked at him and cowered. Yes, genius as he is, he positively cowered. 'And do you mean to say,' he burst out, 'you intend to go on so bleeding me?'

The Colonel smiled a bland smile. 'Sir Charles Vandrift,' he answered, 'I called you just now the goose that lays the golden eggs. You may have thought the metaphor a rude one. But you are a goose, you know, in certain relations. Smartest man on the Stock Exchange, I readily admit; easiest fool to bamboozle in the open country that ever I met with. You fail in one thing—the perspicacity of simplicity. For that reason, among others, I have chosen to fasten upon you. Regard me, my dear sir, as a microbe of millionaires, a parasite upon capitalists. You know the old rhyme:

Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em,

And these again have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum!

Well, that’s just how I view myself. You are a capitalist and a millionaire. In your large way you prey upon society. You deal in Corners, Options, Concessions, Syndicates. You drain the world dry of its blood and its money. You possess, like the mosquito, a beautiful instrument of suction—Founders' Shares—with which you absorb the surplus wealth of the community. In my smaller way, again, I relieve you in turn of a portion of the plunder. I am a Robin Hood of my age; and, looking upon you as an exceptionally bad form of millionaire—as well as an exceptionally easy form of pigeon for a man of my type and talents to pluck—I have, so to speak, taken up my abode upon you.'

Charles looked at him and groaned.

The young man continued, in a tone of gentle badinage. 'I love the plot-interest of the game,' he said, ‘and so does dear Jessie here. We both of us adore it. As long as I find such good pickings upon you, I certainly am not going to turn away from so valuable a carcass, in order to batten myself, at considerable trouble, upon minor capitalists, out of whom it is difficult to extract a few hundreds. It may have puzzled you to guess why I fix upon you so persistently. Now you know, and understand. When a fluke finds a sheep that suits him, that fluke lives upon him. You are my host: I am your parasite. This coup has failed. But don’t flatter yourself for a moment it will be the last one.'

'Why do you insult me by telling me all this?' Sir Charles cried, writhing.

The Colonel waved his hand. It was small and white. 'Because I love the game,' he answered, with a relish; 'and also, because the more prepared you are beforehand, the greater credit and amusement is there in besting you. Well, now, ta-ta once more! I am wasting valuable time. I might be cheating somebody. I must be off at once. . . . Take care of yourself, Wentworth. But I know you will. You always do. Ten per cent is more usual!'

He rowed away and left us. As the boat began to disappear round the corner of the island, White Heather—so she looked—stood up in the stern and shouted aloud through her pretty hands to us. 'By-bye, dear Sir Charles!' she cried. 'Do wrap the rug around you! I'll send the men to fetch you as soon

I climbed to the top of the cliff.as ever I possibly can. And thank you so much for those lovely flowers!'

The boat rounded the crags. We were alone on the island. Charles flung himself on the bare rock in a wild access of despondency. He is accustomed to luxury, and cannot get on without his padded cushions. As for myself, I climbed with some difficulty to the top of the cliff, landward, and tried to make signals of distress with my handkerchief to some passer-by on the mainland. All in vain. Charles had dismissed the crofters on the estate; and, as the shooting-party that day was in an opposite direction, not a soul was near to whom we could call for succour.

I climbed down again to Charles. The evening came on slowly. Cries of sea-birds rang weird upon the water. Puffins and cormorants circled round our heads in the gray of twilight. Charles suggested that they might even swoop down upon us and bite us. They did not, however, but their flapping wings added none the less a painful touch of eeriness to our hunger and solitude. Charles was horribly depressed. For myself, I will confess I felt so much relieved at the fact that Colonel Clay had not openly betrayed me in the matter of the commission, as to be comparatively comfortable.

We crouched on the hard crag. About eleven o'clock we heard human voices. 'Boat ahoy!' I shouted. An answering shout aroused us to action. We rushed down to the landing-place and cooee'd for the men, to show them where we were. They came up at once in Sir Charles's own boat. They were fishermen from Niggarey, on the shore of the Firth opposite.

A lady and gentleman had sent them, they said, to return the boat and call for us on the island; their description corresponded to the two supposed Grantons. They rowed us home almost in silence to Seldon. It was half-past twelve by the gatehouse clock when we reached the castle. Men had been sent along the coast each way to seek us. Amelia had gone to bed, much alarmed for our safety. Isabel was sitting up. It was too late, of course, to do much that night in the way of apprehending the miscreants, though Charles insisted upon dispatching a groom, with a telegram for the police at Inverness, to Fowlis.

Nothing came of it all. A message awaited us from Lord Craig-Ellachie, to be sure, saying that his son had not left Glen-Ellachie Lodge; while research the next day and later showed that our correspondent had never even received our letter. An empty envelope alone had arrived at the house, and the postal authorities had been engaged meanwhile, with their usual lightning speed, in 'investigating the matter.' Césarine had posted the letter herself at Fowlis, and brought back the receipt; so the only conclusion we could draw was this—Colonel Clay must be in league with somebody at the post-office. As for Lord Craig-Ellachie's reply, that was a simple forgery; though, oddly enough, it was written on Glen-Ellachie paper.

However, by the time Charles had eaten a couple of grouse, and drunk a bottle of his excellent Rudesheimer, his spirits and valour revived exceedingly. Doubtless he inherits from his Boer ancestry a tendency towards courage of the Batavian description. He was in capital feather.

'After all, Sey,' he said, leaning back in his chair, 'this time we score one. He has not done us brown; we have at least detected him. To detect him in time is half-way to catching him. Only the remoteness of our position at Seldon Castle saved him from capture. Next set-to, I feel sure, we will not merely spot him, we will also nab him. I only wish he would try on such a rig in London.'

His spirits revived.

But the oddest part of it all was this, that from the moment those two people landed at Niggarey, and told the fishermen there were some gentlemen stranded on the Seamew's island, all trace of them vanished. At no station along the line could we gain any news of them. Their maid had left the inn the same morning with their luggage, and we tracked her to Inverness; but there the trail stopped short, no spoor lay farther. It was a most singular and insoluble mystery.

Charles lived in hopes of catching his man in London.

But for my part, I felt there was a show of reason in one last taunt which the rascal flung back at us as the boat receded: 'Sir Charles Vandrift, we are a pair of rogues. The law protects you. It persecutes me. That's all the difference.'