Chap. CCLXXXIV.—Of the Perspective of Colours.

The air will participate less of the azure of the sky, in proportion as it comes nearer to the horizon, as it is proved by the third and ninth proposition[1], that pure and subtile bodies (such as compose the air) will be less illuminated by the sun than those of thicker and grosser substance: and as it is certain that the air which is remote from the earth, is thinner than that which is near it, it will follow, that the latter will be more impregnated with the rays of the sun, which giving light at the same time to an infinity of atoms floating in this air, renders it more sensible to the eye. So that the air will appear lighter towards the horizon, and darker as well as bluer in looking up to the sky; because there is more of the thick air between our eyes and the horizon, than between our eyes and that part of the sky above our heads.

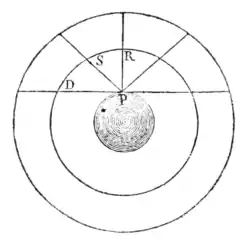

For instance: if the eye placed in P, looks through the air along the line P R, and then lowers itself a little along P S, the air will begin to appear a little whiter, because there is more of the thick air in this space than in the first. And if it be still removed lower, so as to look straight at the horizon, no more of that blue sky will be perceived which was observable along the first line P R, because there is a much greater quantity of thick air along the horizontal line P D, than along the oblique P S, or the perpendicular P R.

- ↑ These propositions, any more than the others mentioned in different parts of this work, were never digested into a regular treatise, as was evidently intended by the author, and consequently are not to be found, except perhaps in some of the volumes of the author’s manuscript collections.