A Failure

BY JENNETTE LEE

THE wedding was over and the last of the guests had gone. Mrs. Melvin had been afraid that some one would insist on remaining. The older married daughters had, indeed, objected that she must not be left alone—that one of them would stay for the night at least, and one or two of the children. But Mrs. Melvin had put them firmly aside.

"There is not the least need. I have your father; and the servants are excellent. It will seem good to have the house quiet for a little," she had added.

So they had all gone; and the house was left to the strange stillness that follows on a birth, or a death, or a wedding.

In some distant room the host, in shining shoes, was pottering about, turning out the extra lights and looking, a little wistfully, at the banks of flowers and ferns and trailing vines. He would have been glad to have some one in the house to bridge over the silence. But for once he had not been consulted.

"I prefer that they should go," his wife had said, when he had suggested mildly that some one might like to stay with them.

He had looked at her a little doubtfully, but he had not urged the point. Mary had never spoken to him in just that tone before; it was courteous and gracious, as always, but it was final. She was probably tired with the fuss of the wedding. It was right that she should have her way. His thought ran back over the twenty-eight years of their married life. He could not remember that she had ever crossed him in a wish. ... He had come to the library door and stood looking in with a smile. The floral arch was still in place, where Tottie had stood—his little Tottie. She was the last of the children. It seemed only yesterday that he was carrying her up to bed on his shoulder—and now she was married. He fumbled for his glasses and looked about for the daily paper. It was not in its accustomed place. But he found an old one and sat down by the library table, rubbing the glasses.

Out in the dining-room Mrs. Melvin had disposed of the remnants of the feast. The broken bits had been set aside for charity; and untouched loaves and fishes were being removed one by one, the servants carrying out her commands with noiseless feet, while she herself attended to the flowers, taking them from their places and snipping each stem before she placed it in the huge pan of water that had been brought in and set on the floor.

As she bent over the flowering things, the lines of her figure, supple and strong, and her face full of clear light, shed a girlishness about her. There was a kind of lightness in it—something set apart, untouched, rarely seen in a woman whose life has been lived. Only the line of the mouth contradicted the clear face and the eyes. As the blunt-pointed scissors came together on the heavy stems the line of the mouth deepened a little, each time, to a kind of firmness—edged with hardness.

She could afford to be hard now. The goal was in sight. She had waited for it through slow-moving years—the goal that a woman may achieve only by waiting, folding the hands over quick heart-beats.

Her mind ran back through the years as she massed the flowers, tossing aside, and snipping, and setting them upright in the fragrant pan. ... She had been only eighteen when she married—just the age of Theodora to-day. But Theodora's life would be very different from hers. She had taken care for that. The child's husband would be her master. He was only twenty-five, but he was a man—born to lead men and to master women. Theodora would have a happy life—and she was the last one. They were all married now, and married rather well. Mrs. Melvin lifted her face with a little sigh of relief. She glanced about the dismantled room with a look of satisfaction. It was almost finished—the life that had smothered her and held her for twenty-eight years. ... She had married a boy—twenty-three years old, but none the less a boy. She had married his blond face and waving hair and tall, lithe limbs. He had been a god to her—a Viking. ... The servants had left the room; and she was alone, gazing into the mass of flowers. Her hands had fallen in her lap and the scissors were idle. She was looking into the face of the man she had married ... so long ago.

She came back from her dream with a little shudder—as she had come back that first night when he had been brought home to her in a drunken stupor, limp and helpless, the even teeth and pink tongue gleaming from behind loose-parted lips. She felt again the quick blush of shame, the shrinking fingers and startled face and swift pain of the girl-wife. ... She rose to her feet, shrugging her shoulders a little and brushing the bits of stem from her lap. She must finish her work. ... No one had guessed what she had suffered that first night, and the next time it had happened—and the next. Her will had mastered his at last. It had not been easy. But it had been done, and now it was over—and the best years of her life. ... The lips grew hard, again as she bent above the roses, setting them in place.

Not even John Melvin himself had guessed the fierce shrinking of the girl and the swift rebound that had mastered him at last. He had drunk the wine that was served every day on his table. He had sipped it with cool, loose lip, looking over the rim of his glass into the clear eyes of his wife. He had chosen her because of her beauty and a kind of charm that he could not define, and her beauty had not failed him, nor her charm.

He was thinking of it now as he sat in the library dozing over the paper.—How well she had looked to-day! ... She should have an easier life now that the children were married. They would go abroad together, he and she—as soon as his term expired. ... He had not wanted the mayorship, but Mary had insisted. He had taken it really to please her. She was always so proud of his holding office of any kind. It was the one foolish thing about Mary. He dwelt on the thought lovingly. ... Where was she? She would be tired out. He glanced up at the clock a little fretfully. She ought to have stopped long ago. But it was not easy to stop Mary. He smiled tolerantly and took up his paper again.

Out in the dismantled room the woman was looking about her slowly, taking a last inventory. It was ready now for breakfast. The servants had only to carry the pan of roses to the cellar and sweep up the litter her scissors had made. She gave the final directions and passed into another room. The mass of flowers and heavy sweetness oppressed her. She still held the scissors in her hand, but she turned out the lights and passed hastily on. To-morrow let them be bundled out and burned. Let them wither on their stems where they stood. Her work was done. To-morrow life would begin.

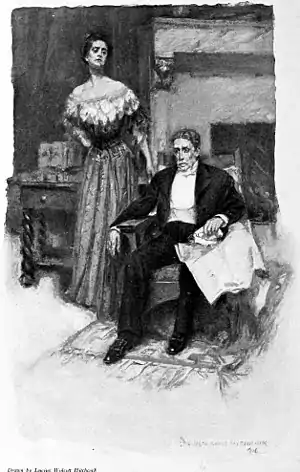

She had reached the door of the library. John Melvin, looking up from his paper with a smile, saw her standing there. He may have been reading or he may have been only dozing between the lines. But his face lighted up swiftly when he saw her.

"All through?" He asked it casually and kindly.

"All through." She stood sombrely by the table, her hand resting lightly on its shining surface.

He continued to look at her, his face filled with admiration. Then he took off his glasses and blew his nose gently.

"You are not old," he said, proudly.

"I do not feel old." She waited a minute for the right words to come. After all, she did not want to hurt him. He was only a fool. He had not meant to ruin the best years of her life.

"I want my share of the property." She said it baldly. The words escaped her without volition.

He stared at her a second. Then he looked away. "It is all yours," he said, after a minute.

"I know But I want it divided."

He was looking down now at his paper.

"What do you mean?" He spoke the words very low.

"I mean that I want a chance to live—my own life." The words were full of repressed force. "I have lived yours—twenty-eight years."

"You want more money? You shall have it—all you need—or want." The words came slowly. He did not look up. His hands were fumbling a little at the paper on his knees.

"I want half the property."

He looked up now—startled. "Wha—what for?" he demanded.

"That is my affair. I want it—I need it," she added, more gently.

"I can't give it to you." His lips came together almost firmly beneath the gray mustache.

"Yes, you can give it to me." Her attitude had changed subtly. Once more she must possess his will with hers—once more. ... She had thought to be free without it—to compel him in freedom. But the habit of years held them.

"You can give it," she repeated, quietly, "for you will not have me to support. I am going away."

He looked up helplessly. "When are you coming back?" he asked. His will was hers. But far back in the recesses something was struggling.

"Never."

The clock across the room ticked the sound and masses of flowers weighted with sweetness spread it about them.

The man sat with his head a little bowed. "Are you going to live—with the children?" he asked. The words groped their way through a kind of darkness. "I don't seem to understand, Mary." It was almost a cry.

"You don't need to understand." She barely heard him—so bent was she on freedom. "I shall not live with the children. I may visit them—sometimes. But I want to go away—by myself. To live my life, clean and free—" She broke off suddenly. "Never mind the reasons. Let me go."

"You shall not go." He got suddenly to his feet, confronting her.

"Oh yes, I shall go." Her quiet eyes met his. "I shall go because you will want me to—when I tell you."

He paused irresolute, his eyes seeking hers in disbelief.

"I am going because I must." The words came clear and distinct. "For years I have borne your soul— Soul?" She laughed a little. "Bah!" Her finger-tips spread themselves a little. "I hate you, I tell you. Now will you let me go!"

The man's hand groped for the chair behind him. He sat down, wiping the moisture from his forehead. He seemed suddenly shrivelled. His clothes hung loosely on him and his shoulders bent themselves like those of an old man. He did not lift his gaze to the woman standing above him, towering and straight. He seemed hardly to know that she was there. His lips mumbled a little and trembled to silence.

She waited a minute. Then she went across the room and lighted a candle. For twenty-eight years she had lighted his bedroom candle for him. She placed it in the nerveless fingers. "Go to bed," she said, gently.

He got to his feet and shuffled from the room—slowly still, like an old man. At the door he turned a little. "Why, Mary! Mary!"

She did not turn nor look at him, and he went into the hall.

When the door had closed, she lifted her head a little and drew a deep breath. Then she raised her folded hands high above her head and stretched them wide in a gesture of freedom.

They fell to her sides, and she stood very still, gazing at something—with wide, intent eyes. ... It was a vision that was often with her—a vision of the world—of men and women—like a very busy community of very black ants hurrying hither and thither—their black legs alive with importance—eating and drinking and sleeping; sometimes they laughed, sometimes they cried, but more often they hurried. One ant she seemed to see oftener than others—a female ant with long hair that it did up, standing in front of the mirror and coiling it anxiously about its round, black head, peering in the glass for wrinkles. Sometimes this ant grew sad and seated herself to weep, digging her long black feelers into her unhappy eyes. When this occurred, the woman, looking on, invariably laughed.

She laughed now, a dry, trembling laugh, as she lighted her bedroom candle.

HE SEEMED SUDDENLY SHRIVELLED

In the morning John Melvin was early in his place at table. He had been there for five minutes, reading his paper fitfully and glancing toward the door. The hand that held the paper trembled a little, and the face, beneath its look of alertness, was gray and worn. When the handle of the door turned, his face cleared a little, and his eyes brightened as they rested on the youthful figure and fresh, clear face ... she was his wife—and a mighty fine woman, too. She had been tired last night, and had said more than she meant. But he had something that would make things all right. He patted the pocket-book that lay beside his plate as he said good morning.

She responded absently. Her attention was preoccupied. She had hoped to get away to-day. But there were many details to be attended to. She might have to stay over another night.

"Mary!" He had cleared his throat a little, huskily.

"Yes?" She had made a memorandum on a slip of paper at her side. "Yes?" She did not look up. She was considering the question of the winter blankets—whether it was too early to send them to the cleaner.

"I wanted to give you this." He held out the blue slip of paper.

She took it in absent fingers.

He closed his purse with a little of the old air of importance. "I shall give you the same every quarter," he said.

She looked down at it, and a clear color came into her face—the flush of swift anger.

She waited a minute. Then she spoke, in even tones. "I shall not speak of this again. I do not want your quarterly check—like a pensioner. I want my rightful share of the property. There is enough for us both. Do you suppose that I do not know?" She laughed a little bitterly. "You will see Mr. Adams to-day and make assignments. If you need to consult me, I shall be in my room."

Something in his face as she handed him back the check stayed her hand for a minute. It was like the look in the face of her oldest boy, Harold, once when she had misjudged him. She had never forgotten the look. The boy had worshipped her, and in trying to please her had blundered. ... She had never thought that the boy looked like his father. The children were not like him. ... But something in the look stayed her hand a minute—something that was not asking for itself. ... She remembered how the boy had told her, with sobs, that he couldn't bear to have her seem so wrong. ... She brushed away the cobweb of thought.

Later, when John came to tell her that Adams would not be able to attend to things until to-morrow, she merely nodded absently. She had found so many things to be done that she would not be able to get off in any case.

She did not notice that John had not gone to the office. She had dropped the thought of him. The burden that had rested on her for twenty-eight years had fallen from her. She moved, a free being, in a kind of misty vacuum. Nothing could touch her now. The little black ants had scattered and fled. She folded blankets and cleaned cupboards in a haze of rosy light. A third of her life was left her. She would live it gloriously.

When the lawyer came, the next day, she was still busy with the bedding and linen and silver. Summoned to the library, she came down hastily, without removing the white cap that she had put on to protect her hair.

The lawyer glanced more than once from the clear, fresh face under its white border to that of the man on the opposite side of the table. The man's face seemed to have suddenly grown old. But there was something else in it—something that puzzled the lawyer incongruously—a kind of empty look of youth. ... The legal, impartial gaze scanned it anew. ... Ah, that was it—the very look! It was John Melvin, twenty-five years ago—or was it thirty? ... The lawyer's pen was racing fast over the paper, but not swifter than his mind over the past. He ought to know—if any one— how John Melvin had looked. They had been rivals for the hand of the same woman, and Melvin had won. The lawyer's gaze sought again the face in the white cap. He had never understood it. ... John Melvin was weak. He had always been weak. Yet somehow he had always won out. And now he was sitting across his library table, making over to his wife the half of a fortune that any one might be proud to own. It was natural that he should wish to give it to her now, in this way, rather than trust the chances of a will. ... They had always been strangely equal—this man and woman—more like comrades than married people. The lawyer's keen mind recognized it grudgingly, even while he failed to account for it. He had looked for failure when they were married, for a gradual falling apart. He had known John Melvin through and through, and he knew Mary Parkman. He had not believed that they could live together in harmony a single year; and lie had watched with puzzled eyes the transformation of the man, the serene, untroubled life of the woman. Of late years he had given over thinking of it. He himself had married. He had plenty of problems of his own, and children. But this morning as he sat in the home-like room, asking the crisp, legal questions and writing swiftly, it all came back to him with puzzling freshness. The intervening years were wiped away as he looked into John Melvin's face—weak and old, with something of the boy in it. The lawyer finished his papers and handed them across for signature. The two servants came in, with stiff, respectful fingers, to witness the deeds, and the transaction was over.

The lawyer followed the mistress of the house into the hall, standing for a minute in the outer door to look into the pleasant yard.

Then he turned back a little. "John is not ill?" It was a question of curiosity, yet prompted somehow by something deeper beneath it.

"John?" She paused for a minute with one hand on the balustrade, looking down at him. "No, he is not ill—only tired, I suppose—from the wedding—like the rest of us." She laughed lightly.

"You are not tired!" He was looking up at her, the puzzled look still in his eyes. "You are your own daughter!" he declared.

She smiled beneath the white border of the cap—a smile that startled him, so luminous was it, and clear and care free, "I am young," she said. "I mean never to grow old."

"You never will," he replied, lifting his hat as he left her.

She went slowly up the stairs, the little smile still on her lips.

In the library the old man with the boy's face fumbled with the papers, gathering them up in trembling hands and putting them away in the table drawer. He turned the key in the lock slowly. Then he walked vaguely out into the yard toward the spring sunshine. The air had the keen freshness of early May, and he shivered a little as he walked. Now and then stopped to look at the new buds that were opening to the light.

She had ignored the lawyer's question, but it came back to her now and then as she worked. She had her meals brought to her up-stairs to save time, and she did not see her husband's face again, but the lawyer's question brought it to her—haggard and a little bewildered. ... Of course he would mind. She had expected that. She could not help its being a shock. She had borne shocks—a long time. It was his turn now. Her face hardened a little. ... There should be no scandal. She would manage that—as she had always managed. There were a few calls she must make to explain her going. Every one would understand that she needed rest. She was going away for a little while. The servants understood that she would return. It would be easy, later, to delay the return, from time to time. Yes, there would be problems. But they would be easy compared with those she had faced so long.

She stretched her arms in a free gesture and went to change her dress for calling. Before she went out she gave instructions for dinner. She would take it in the dining-room as usual. ... She could endure his presence another hour. The trunks were packed, her house in order. In the morning she would be free—forever. To-night she would serve the last hour of bondage.

But she was not called on to perform it. A message came from her husband. He hoped she would excuse him. He was not feeling well. It was nothing serious—a little indisposition. She was not to worry. ... She ate her dinner alone. When it was finished she ascended the stairs, pausing a minute, irresolute, at the top. Then she went on to her own room. She slept soundly all night—a dreamless sleep.

In the morning the master of the house was still absent. She hesitated a minute before she rapped on his door with quick, decided touch. When she opened it and went in, he was lying huddled forward, a look of vacant stupor on his face.

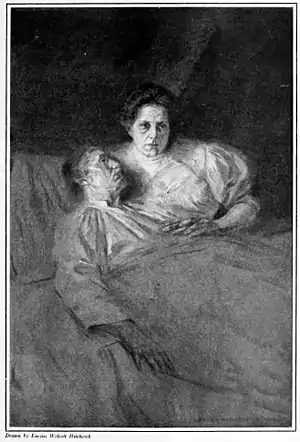

"I AM GLAD YOU WILL BE FREE—MARY"

She shivered a little as she bent over him. Her hand touched his forehead and travelled to his wrist. She waited a minute, with bent head, before she straightened herself and rang the bell.

When the doctor arrived she had exchanged her travelling-dress for a white one, and her hair was coiled close about her head.

The doctor examined the patient with grave care. "A shock of some kind—trouble with the brain." He was trying to shield the wife from the worst.

But she refused to be put off. "He is very ill?" she said, quietly.

"Perhaps— Yes. It is not always easy to tell—at once. Better get a nurse—"

"Not yet. I can take care of him for a while." She turned on him suddenly. "Tell me just how he is."

His eye dropped to the vacant face before them. "There is as much hope there as you see. Look."

The house settled down to the quiet that surrounds a sick-room. Bells were muffled and voices hushed. In a distant room, Mary Melvin's trunks were unstrapped and unpacked and their contents noiselessly returned to closets and bureau drawers. Her freedom was delayed a little, while she sat by the bed listening to quick, irregular breaths that came through loose lips—one, two, three—one, two, three—one, two, three—and then the long-drawn shivering sigh—and one, two, three—one, two, three—again and again. The rhythm beat itself into her brain.

She sat there watching her freedom being delayed a little. She had the hope that she saw in her husband's face. No more. She could not have told what its dull stare said to her. Nor whether she wished him to live. Had she been asked, she would have said that there was no hope for him or for her. They had had their life and this was the end—to be bound together forever in torment—unable even to die. Yet she would not leave her place, day or night. She waited for something. She could not have told what.

Yet when it came it was so quiet that it was like waking from a long sleep. His eyes opened and looked out at her—from a far place—the eyes that the girl had known. Slowly the loose lips moved themselves.

"I am glad you will be free—Mary."

She leaned forward, holding her breath, but there was no sound. The face, like a mask, had resumed its vacant hold. The eyes had closed again.

Yet something had passed from them to her. She straightened herself with a little cry and stood up, the tears running down her face unheeded. She stretched out her hands, groping vaguely. Then they fell to her sides, and she stood very still, listening. ... The beat of the breath had changed. Yes, it was swifter now—and fainter—and halting a little in the sigh that came—slowly—at the last.

She rang a bell and gave quick directions. The fight had begun. She bent to it all the force of her will. He should not die. He should come back from the far place—the man who had won her. Her soul and her will were his. He should not die.

And all the time, while the fight went on, hordes of tiny gnomes carrying heavy burdens climbed the steep hill of her vision, struggling to the top, panting, eager, hard pressed,—their tiny bodies strained against the load, their patient, grotesque faces lifted to the light,—striving against odds, but always striving.

She stood by the doctor, listening to his final words; and the doctor as he looked into her face was struck anew with its beauty. He had always thought Mrs. Melvin a beautiful woman; a little cold, perhaps, and self-centred, but beautiful—like a statue—some German Madonna. But now she was different. The face was alight—something trembled in it, like the color of a flower in spring or the passing of the wind over the grass; something swaying and fine and deep; something—... No. ... The doctor could not tell. He was not a poet. But he knew, looking into Mary Melvin's face to-night, that he would give a great deal to help her through. He had seen death held at bay before, but never like this. The light in the woman's face would not quench, and the face on the pillow was turned to it blank and untouched.

Only the quick breathing from the lips broke the quiet of the room.

"I can stay," said the doctor, slowly, "if you would like me to?"

She shook her head. A flitting paleness had crossed the lips. "It is to- night?" The words were almost a whisper. But the color had come back to her face.

"Would you like me to stay?" answered the doctor.

"No—no. You could not help?" quickly.

"Only to be here."

"No, do not stay." She laid her hand on his arm, motioning him toward the door. "Do not stay. I think I would rather be alone."

Slowly the night wore itself out. The long minutes shaped themselves, out of time, and laid themselves on her heart, with their burden of mystery and light. ... Now she had missed it all—the meaning of it! Life was love—and love. Love. The dark minutes filled the word from their cup ... and she had cast it aside—blind and righteous! Blind, blind! The face on the pillow had turned a little. She bent above it, looking at it long ... Ah, he had known—stupid, blundering boy. He had held it always. Love—for her, for the children, for every one. He had known it—and she had lost. But now she knew. He had waited to give it to her—when his heart broke. ... She fell on her knees by the bed.

Slowly the morning came upon the hills. The face on the pillow had grown subtly quiet. The lines relaxed, and into the mask of stupor crept a faint light that flickered and paled—and fluttered. A sigh that was scarcely a breath escaped the open lips. They closed gently in a deeper breath as a child stirs in sleep.

Mary Melvin raised her head with quick, questioning glance. Then she crept closer, on her knees, till her face touched the quiet cheek. It turned to her—the shadow of a breath—and the quiet, even breathing went on—like the faintest music that might come at sunrise, out of the deep night, the turn of the tide, the freshness of life—flowing in. ... When she lifted her face it was wet with tears—half blinded, she gazed at the sleeping face. Then she rose from her knees and groped to the window, rolling up the heavy shade and letting in the day.

In the east the sky was red, and along the road beyond the wall two laborers, with bowed backs and heavy hands and feet, were going to their work. They walked with clumsy, swinging gait, their great dinner-pails dangling from their hands, and the light of the east in their faces. Somewhere below, in the shrubbery, a bird broke into singing, and in the room behind her the lightest breath came and went, like a child in sleep.

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1927.

The author died in 1951, so this work is also in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 70 years or less. This work may also be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.