TRUMPET (Fr. Trompette; Ger. Trompete, Trummet, Tarantara; Ital. Tromba, Tr. doppia, Clarino). It is unnecessary to seek for the origin of an instrument which was already familiar when the Mosaic books were written; at Jericho performed one of the earliest miracles; figured in the Hebrew ritual; preluded to the battles around Troy; is carved on the stone chronicles of Nineveh and Egypt; and for which China claims, in the form of the 'Golden Horn' a far greater antiquity than these.

If, instead of following the vertical ordinate history, we move along the horizontal line of ethnology, we find its gradual development from the shell, the cow, buffalo or ram's horn through the root[1] hollowed by fire, to the wooden Alpenhorn bound with birch bark; thence to the Zinckes and Cornets of ancient Germany, up to the Tuba and Lituus of Rome. Both of these, which were real Trumpets, Rome borrowed, inherited, or stole; the former from Etruscan, the latter from Oscan, originals. One of the Etruscan Tubas in the British Museum has a mouthpiece perfectly characteristic, and capable of being played on; two spare mouthpieces standing beside it as perfect as though just turned.

In the typical shapes above named we have evidence of an early subdivision into two forms of the sounding tube which has now become fruitful of musical results. For whereas the large-bored conical Tuba still keeps its name, and is the mother of Bugles, Serpents, Horns, Cornets à piston, Euphoniums, Bombardons and the like; the Lituus, which Forcellini derives from the Greek λιτὸς, tenuis, is the small-bored cylindrical Trumpet, and the father of all Trombones. It was early seen that two distinct varieties of tone quality could thus be obtained; the large cone and bell favouring the production of the fundamental note and the lower partial tones; whereas the long contracted pipe broke easily into harmonics, and spoke freely in its upper octaves. Hence the Orchestral Trumpet, as now used, is really an 8-foot pipe overblown, like a Harmonic stop on the Organ; to this it owes its keenness, pungency, power of travelling, and its marvellous superiority in timbre over the 4-foot Cornet.

That the distinction between the Roman Tuba and Lituus is real, needs for proof no more scholarship than is contained in Horace's First Ode to Mæcenas:

Multos castra juvant, et lituo tubæ

Permixtus somtus.

On this passage Forcellini comments, 'Sunt qui lituum a tubâ distinguunt, ex eo quod ille equitum sit, hæc vero peditum.' The distinction is good to-day. The Tuba was the 'Infantry Bugle'; the Lituus the 'Cavalry Trumpet.'

The derivation of lituus may indeed be originally Greek; certainly it is proximately from the hooked augur's staff of the Oscans, which had been Mercury's wand, and has become the bishop's crozier. Cicero sets the etymology hindside foremost. 'Bacillum,' he says of the staff, 'quod ab ejus litui quo canitur similitudine nomen invenit.' It might as well be said that the horse was made with four legs and a round body to fit the forked shafts of the cart.

Both Tuba and Lituus figure on Trajan's column, in the triumphal procession. Vegetius defines the former: 'Tuba—quæ directa est, appellatur.' This straight form reappears even in more recent times, as in a fine picture by Baltazarini; by comparing it with the average height of the players, it may be estimated at about seven feet long. The Lituus is figured by Bartolini from a marble Roman tombstone with the inscription

M. Julius Victor

ex collegio

Liticinum Cornicinum.

which is perhaps the first mention of a society of professional musicians.

A farther development of the two types above named involved the means of bridging over the harmonic gaps. For this purpose the slide was obviously the first in date. [See Trombone.] Its application to the Trumpet itself came later, from the reason named above, that in its upper part the harmonic series closes in upon itself so that at a certain point the open notes become all but consecutive and form a natural scale. This can be accomplished by a good lip, unassisted by mechanism, and is probably one of the reasons why Bach, Handel, and the older musicians write such extremely high parts for the instrument.[2] The Bugle type, on the other hand, developed early into hand-stopped side holes, as in the Serpent, followed by the same, key-stopped in the Key-Bugle, keyed Serpent, and the identical instrument with the mongrel Greek appellation of Ophicleide. Considerably later the prodigious brood of Valve or 'Ventil' contrivances allied itself to the Bugles with fair success. On the Trumpet[3] and Trombones they are a complete failure, as they obscure the upper harmonics, the main source of the characteristic tone.

In the following description of the modern Trumpet the writer has been materially assisted by an excellent monograph published by Breitkopf & Härtel of Leipzig in 1881, and named 'Die Trompete in Alter und neuer Zeit, von Hermann Eichborn.' In acknowledging his obligations to the work he can heartily advise its study by those who wish for more detail than can be given in a dictionary.

The simple or Field Trumpet is merely a tube twice bent on itself, ending in a bell. Hence its Italian name Tromba doppia. The modern orchestral or slide Trumpet, according to the description of our greatest living player,[4] is made of brass, mixed metal, or silver, the two latter materials being generally preferred. .jpg.webp) It consists of a tube sixty-six inches and three quarters in length, and three eighths of an inch in diameter. It is twice turned or curved, thus forming three lengths; the first and third lying close together, and the second about two inches apart. The last fifteen inches form a bell. The slide is connected with the second curve. It is a double tube five inches in length on each side, by which the length of the whole instrument can be extended. It is worked from the centre by the second and third fingers of the right hand, and after being pulled back is drawn forward to its original position by a spring fixed in a small tube occupying the centre of the instrument. There are five additional pieces called crooks, a tuning bit, and the mouthpiece.

It consists of a tube sixty-six inches and three quarters in length, and three eighths of an inch in diameter. It is twice turned or curved, thus forming three lengths; the first and third lying close together, and the second about two inches apart. The last fifteen inches form a bell. The slide is connected with the second curve. It is a double tube five inches in length on each side, by which the length of the whole instrument can be extended. It is worked from the centre by the second and third fingers of the right hand, and after being pulled back is drawn forward to its original position by a spring fixed in a small tube occupying the centre of the instrument. There are five additional pieces called crooks, a tuning bit, and the mouthpiece.

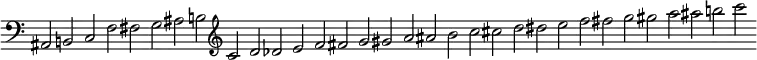

The first crook and mouthpiece increase the length of the whole tube to 72 inches, and give the key of F. The second gives E, the third, E♭, the fourth, D. The fifth or largest crook in general use is 25½ inches long, making the total length of the instrument 96 inches, and giving the key of C. A D♭, B♮, and B♭ crook may be used, but are not often required. The mouthpiece is turned from solid brass or silver, and its exact shape is of greater importance than is generally supposed. The cup is hemispherical, the rim not less than an eighth of an inch in breadth, level in surface, with slightly rounded edges. The diameter of the cup differs with the individual player and the pitch of the notes required. It should be somewhat less for the high parts of the older scores.

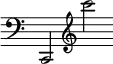

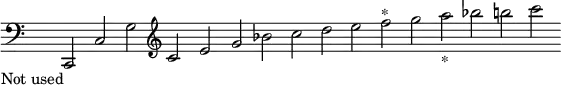

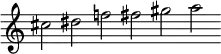

Practically the useful compass begins with the Clarinet E and ends with the G in alt.

The Natural notes of the Trumpet.

Scale of the Slide Trumpet. (Harper).

A number of alternative notes are given in good instruction books, such as that already quoted, by which, on the same principle, other notes may be tempered to suit the harmony, and Mr. Harper very judiciously sums up his directions by saying: 'It will therefore be seen that the required length of slide for certain notes varies with each change of crook, consequently when it is necessaiy to extend the slide, the ear must assist the fingers.' This fact has already been noted in regard to the Trombone, and exists to a certain extent in the Bassoon and Ophicleide. It is quite impossible on the Valve Trumpet.

The mediæval use of the Trumpet is well given in Eichborn's book already named; but somewhat exceeds our present limits. He states however that Henry VIII of England had 14 Trumpeters, one 'Dudelsack* (or bagpipe), and 10 Trombones in his band, and Elizabeth, in 1587, 10 Trumpets and 6 Trombones. Indeed, it is in the 16th century, according to him, that the 'building up of the art of sound' made a great advance. He divides the band of that day, 'the day of Palestrina and of Giovanni Gabrieli' into seven groups, of which group 3, Zinken or Cornets, Quart-Zinken, Krumm-horns, Quint-Zinken, Bass-Zinken and Serpents of the Bugle type, group 6, Trumpets, 'Klarinen,' and 'Principal or Field-Trumpets,' with group 7, the Trombones, from soprano to bass, most concern us.

At this period falls in Baltazarini's picture, named before, of the marriage of Margaret of Lorraine with the Duke of Joyeuse, of which we have the music as well as the pictorial representation. Claudio Monteverde, about 1610, has 1 Clarino, 3 Trombe and 4 Tromboni, in his orchestra; and Benevoli in a mass at Salzburg Cathedral in 1628 has 'Klarinen, Trompeten, Posaunen'; Prætorius in 1620, already quoted under Trombone (p. 176) waxes enthusiastic, and says 'Trummet ist ein herrlich Instrument, wenn em gute Meister, der es wohl und künstlich zwingen kann, daruber kömmt.'

About this time began the curious distinction into Clarini and Principale which is found in Handel's scores, and especially in the Dettingen Te Deum. The Principale was obviously a large-bored bold-toned instrument resembling our modern Trumpet. It was apparently of 8-foot tone as now used. To the Clarino I and II of the score were allotted florid, but less fundamental passages, chiefly in the octave above those of the Principale. They were probably of smaller bore, and entirely subordinate to the 'herrlich' Principale, both in subject and in dominance of tone. A like arrangement for three Trumpets occurs in J. S. Bach's Choralgesang 'Lobe den Herrn,' though the Principale is not definitely named. The mode of scoring is an exact parallel to that for the three Trombones. A good example of it also occurs in Haydn's Imperial Mass, where, besides the 1st and 2nd Trumpets, there is a completely independent 3rd part of Principale character.

Beethoven's use of the Trumpet is in strong contrast to his use of the Horn. The Horn he delights to honour (and tease), the Trumpet he seldom employs except as a tutti instrument, for reinforcing, or marking rhythms. He takes it so high as to produce an effect not always agreeable; see the forte in the Allegretto of Symphony No. 7 (bar 75) and in the Allegro assai of the Choral Symphony (Theme of the Finale, bar 73). In the Finale of the 8th Symphony however there is an F♮ prolonged through 17 bars, with masterly ingenuity and very striking effect. An instance of more individual treatment will be found in the Recitative passage in the Agnus of the Mass in D; and the long flourish in the overtures to Leonora, nos. 2 and 3, (in the no. 2 an E♭ Trumpet and in triplets, in the no. 3 a B♭ one and duple figures,) can never be forgotten. But on the whole the Trumpet was not a pet of Beethoven's.

Schubert uses it beautifully in the slow movement of the great Symphony in C as an accompaniment pianissimo to the principal theme.

Mendelssohn wrote a 'Trumpet overture,' but the instrument has no special prominence, and it is probable that the name is merely used as a general term for the Brass.

The only successful attempt to apply valves to this instrument is the 'Univalve Trumpet' of Mr. Bassett, who brought it under the notice of the Musical Association in 1876. It is the ordinary Slide Trumpet, with the addition of a single valve tuned in unison with the open D, or harmonic ninth—in other words, lowering the pitch a minor tone. This valve—worked by the first finger of the left hand, the instrument being held exactly in the usual manner does not injure in the slightest degree the pure tone of the old Trumpet, the bore of the main tube remaining perfectly straight. By the use of this single valve and the slide, it is possible to produce a complete scale, major or minor, with a perfection of intonation only limited by the skill of the player, as it is essentially a slide instrument. The valve not only supplies those notes which are false or entirely wanting in the ordinary Slide Trumpet (including even the low A♭ and E♭ when playing on the higher crooks), but greatly facilitates transposition and rapid passages, while comparatively little practice is required to become familiar with its use.[ W. H. S. ]

- ↑ A good example of this, with a cupped mouthpiece scooped in the wood, which could be played on, was shown at the Loan Exhibition of Scientific Instruments by Mr. Bassett, from Africa.

- ↑ A Trumpet capable of producing the high notes in Bach's Trumpet parts has been made in Berlin, and was used in the performance of the B minor Mass under Joachim at the unveiling of the statue at Eisenach in Sept. 1884.

- ↑ In the Monatshefte für Musik-Gesch. for 1881, No. III, is a long and interesting article by Kitner, investigating the facts as to the inventor of the 'Ventil trompete,' which is said to date from 1802 or 1803. The writer seems however to confuse entirely the key-system or 'Klappen Trompete' with the ventil or valve. Valves render the harmonic system of the Trumpet entirely false, besides deadening its tone Eitner's error is exposed in the preface to Eichborn's 'Die Trompete.'

- ↑ Harper's School for the Trumpet. Rudall, Carte & Co.

- ↑ Eichborn names 'Das kontra Register' or 'Posaunen Register,' but says 'es spricht sehr schwer an.'