SUBJECT. The theme, or leading idea, on which a musical Composition is based. A piece of Music can no more be composed without a Subject, than a sermon can be preached without a text. Rich Harmonies, and graceful Passages, may be strung together, in any number; but, if they be not suggested by a leading thought, they will mean nothing. The 'leading thought' is the Subject: and the merit of the Composition based upon that Subject will depend, in the first place, upon the worthiness of the idea, and, in the second, upon the skill with which the Composer discourses upon it.

Subjects may be divided into as many classes as there are classes of Composition: for, every definite Art-form is based upon a Subject in harmony with its own peculiar character.

I. The earliest known form of Subject is the Ecclesiastical Cantus firmus.[1] The most important varieties of this are the Plain Chaunt Melodies of the Antiphon,[2] and those of the Hymn.[3] The former admits of no rhythmic ictus beyond that demanded by the just delivery of the words to which it is set. The latter fell, even in very early times, into a more symmetrical vein, suggested by the symmetry of the Verse, or Prose, cultivated by the great mediaeval Hymnologists, though it was not until the close of the 15th, or beginning of the 16th century, that it developed itself, in Germany, into the perfectly rhythmic and metrically regular melody of the Choral.[4]

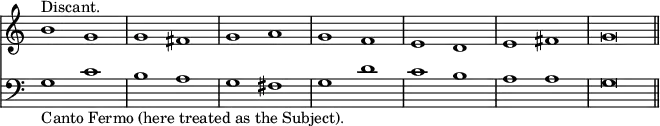

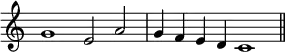

Upon a phrase of this Plain Chaunt, the inventors of Harmony discoursed, at will: in other words, they treated it as a Subject. Composers of the 11th century discoursed upon it by singing a Second Part against the given Subject, in Plain Counterpoint—Note against [5]Note. They sang this Part extempore: and, because it was sung by a second Voice, it was called Discantus—the literal meaning of which is, a Song sung by two Voices. The Song, in this case, was not a very poetical one: but, it was fairly and logically deduced from the Cantus firmus, and therefore perfectly reasonable. Our English verb 'to descant' is derived from this process of deduction, and describes it exactly; for good Discantus contains nothing that is not suggested by the Cantus firmus, as in the following example, from Morley's 'Plaine and easie Introduction.'

When extempore Discant gave place to written Counterpoint, the Cantus firmus was still retained, and sung, by the Tenor, in long sustained notes, while other Voices discoursed upon it, no longer note against note, but, as Art progressed, in passages of Imitation, sometimes formed from the actual notes of the Canto fermo, sometimes so contrived as to contrast with it, in pure Harmony, but with unlimited variety of Rhythm.[6] And this arrangement brought two classes of Theme into simultaneous use—the Plain Chaunt basis of the whole, and the Point of Imitation—the first of which was technically distinguished as the Canto fermo, while the last, in process of time, approached very nearly to the true Subject of the modern Schools. The two forms are very clearly shown in Palestrina's Missa 'Ecce Sacerdos [7]magnus,' in which the long notes of the Canto fermo never fail to present themselves in one or other of the Vocal Parts, however elaborate may be the Imitations carried on in the rest.

II. By a process not uncommon in the development of specific Art-forms, the long-drawn notes of the Canto fermo, after giving birth to a more vivacious form of Subject, fell gradually into disuse; appearing, if at all, by Diminution, or Double Diminution, in notes as short as those formerly used for Points of Imitation. In this manner, the antient Canto fermo became a Subject, properly so called; and, as a Subject, was made the groundwork of a regular Fugue. This process of development is strikingly exemplified in Palestrina's 'Missa L'Homme armé,' in some of the Movements of which the quaint old Melody is treated, in Longs, and Larges, as a Canto fermo, while, in others, it is written in Semibreves, and Minims, as a Fugal Subject.[8]

We do not mean to imply that Palestrina invented this mode of treatment: but only, that he availed himself of all the good things that had been used by his predecessors. The laws of Fugue were established more than a century before his time. Not the laws of what we now call Fugue; but those of the Real Fugue of the Middle Ages—a form of Composition which differs very materially from that brought to perfection by the Great Masters of the 18th century. Real Fugue was of two kinds—Limited, and Free.[9] In Limited Real Fugue, the Imitation was carried on from the beginning to the end of the Composition, forming what we now call Canon. In Free Real Fugue, it was not continued beyond the duration of the Subject itself. In the former case, the Theme of the Composition was called a Guida—that is, a Subject which serves as a 'Guide' to the other Parts, which imitate it, note for note, throughout. In Free Real Fugue, the Theme was called Subjectum, Propositio, or Dux: Soggetto, Proposta, or, if very short, Attacco: Führer, Aufgabe, or Hauptsatz. The early English writers called it Point; but this word is now applied, like the Italian Attacco, to little passages of Imitation only, and the leading idea of the Fugue is simply called the Subject.

The Subject of the Real Fugue—except in the Limited species—was always very short, frequently consisting of no more than three or four notes, after the statement of which the Part was free to move in any direction it pleased. But, the treatment of these few notes was very strict. Every Interval proposed by the leading Part was answered by the same Interval in every other Part. The Answer, therefore, corresponded exactly with the Subject, either in the Fifth, or Fourth, above, or below; and it was necessary that its Solmisation should also correspond with that of the Subject, in another Hexachord.[10] But, the Subject, and the Answer, had each a distinguishing name. The Theme and its reply were called, in various languages, Dux and Comes, Propositio and Responsum, or Antecedens and Consequens; Proposta and Risposta, or Antecedente and Consequenza; Führer and Gefahrte, or Antwort; Demande and Réponse. In English, Subject and Answer; or, more rarely, Antecedent and Consequent.

III. So long as the Ecclesiastical Modes remained in use, Real Fugue was the only species possible: but, as these were gradually replaced by our modern system of tonality, Composers invented a new kind of Fugue, formed upon a Subject the character of which differed entirely from that used by the older Masters. This form of Composition is now called Tonal Fugue.[11] It is generally described as differing from Real Fugue chiefly in the construction of the Answer. Undoubtedly, this definition disposes of its most essential characteristic. But, there are other differences between the two forms which cannot be thus lightly passed over. So far as the Answer is concerned, it is enough to say that its Intervals do not furnish an exact reproduction of those of the Subject; being governed, as to their arrangement, by laws which scarcely fall within the scope of our present article. The Subject, on the other hand, presents so many varieties of form and expression, that it cannot be too carefully considered. In the hands of the Great Masters, it presents an epitome of the entire Fugue, into which nothing is admissible which is not in some way suggested by it: and, in order that it may serve this comprehensive purpose, it must needs be very carefully constructed. The Subjects employed by the great Fuguists are always found to be capable of suggesting a logical Answer, and one or more good [12]Counter-Subjects; of being conveniently and neatly broken into fragments, for purposes of collateral discussion; of intertwining their various members among the involutions of an ingenious Stretto; and of lending themselves to a hundred other devices, which are so intimately connected with the conduct of the Fugue itself, that the necessary qualities of the Subject will be better understood by reference to our general article on Tonal Fugue, than by separate description here.

IV. We have shown how the fathers of Composition treated the Canto fermo: how their immediate successors enveloped it in a network of ingenious Points of Imitation: how, by fusing the Points of Imitation, and the Canto fermo which suggested them, into a homogeneous Theme, the Polyphonic Composers gave birth to that important factor in Composition which we call a Subject: and how that Subject was treated by the great Fuguists of the 18th century. We have now to see how these Fuguists revived the Canto fermo, and employed it simultaneously with the newer Subject. Not that there was ever a period when it fell into absolute desuetude: but, it was once so little used, that the term, revived, may be very fairly applied to the treatment it experienced from Handel and Bach, and their great contemporaries.

And, now, we must be very careful about the terms we use: terms which we can scarcely misapply, if we are careful to remember the process by which the Subject grew out of the Canto fermo. The German Composer of the 18th century learned the Melody of the Chorale in his cradle, and used it constantly: treating 'Kommt Menschenkinder, rühmt, und preist,' and 'Nun ruhen alle Walder,' as Palestrina treated 'Ecce Sacerdos magnus,' and 'L'Homme armé.' Sometimes he converted the traditional Melody into a regular Subject, as in the 'Osanna' of the last-named Mass. Sometimes, he retained the long notes, enriching them with a Florid Counter-point, as in the 'Kyrie.' In the first instance, there was no doubt about the nomenclature: the term, Subject, was applied to the Choral Melody, as a matter of course. In the other case, there was a choice. When the Melody of the Chorale was made to pass through the regular process of Fugal Exposition, and a new contrapuntal melody contrasted with it, in shorter notes, the former was called the Subject, and the latter, the Counter-Subject. When the Counterpoint furnished the Exposition, and the Chorale was occasionally heard against it, in long sustained notes, the first was called the Subject, and the second, the Canto fermo. Seb. Bach has left us innumerable examples of both methods of treatment, in his 'Choral-Vorspiele,' 'Kirchen-Cantaten,' and other works. A fine specimen of the Chorale, treated as a Subject, will be found in the well-known 'S. Anne's Fugue.' In the Motet, 'Ich lasse dich nicht,'[13] the Chorale 'Weil du mein Gott und Vater bist,' is sung, quite simply, in slow notes, as a Canto fermo, against the quicker Subject of the Fugue. In the 'Vorspiel,' known in England as 'The Giant,' the Chorale 'Wir glauben all' an einen Gott,' forms the Subject of a regular Fugue, played on the Manuals, while a stately Counter-Subject is played, at intervals, on the Pedals. A still grander example is the opening Movement of the 'Credo' of the Mass in B minor, in which the Plain Chaunt Intonation, 'Credo in unum Deum,' is developed into a regular Fugue, by the Voices, while an uninterrupted Counterpoint of Crotchets is played by the instrumental Bass. In neither of these cases would it be easy to misapply the words Subject, Counter-Subject, or Canto fermo; but, the correct terminology is not always so clearly apparent. In the year 1747, Bach was invited to Potsdam by Frederick the Great, who gave him a Subject, for the purpose of testing his powers of improvisation. We may be sure that the great Fuguist did full justice to this, at the moment: but, not contented with extemporising upon it, he paid the Royal Amateur the compliment of working it up, at home, in a series of Movements which he afterwards presented to King Frederick, under the title of 'Musikalisches Opfer.' In working this out, he calls the theme, in one place, 'Il Soggetto Reale'; and, in another, 'Thema regium.' It is quite clear that in these cases he attached the same signification to the terms Thema and Soggetto; and applied both to the principal Subject; treating the Violin and Flute passages in the Sonata, and the florid Motivo in the Canon, as Counter-Subjects. But, in another work, founded on a Theme by Legrenzi, he applies the term 'Thema,' to the principal Motivo, and 'Subjectum,' to the subordinate one.[14] We must suppose, therefore, that the two terms were in Bach's time, to a certain extent interchangeable.

Handel, though he did occasionally use the Canto fermo as Bach used it, produced his best effects in quite a different way. In the 'Funeral Anthem,' he treats the Chorale, 'Herr Jesu Christ' first as a Canto fermo and then, in shorter notes, as a regularly-worked Subject. 'As from the power of sacred lays' is founded upon a Chorale, sung in Plain Counterpoint by all the Voices; it therefore stands as the Subject of the Movement, while the Counter-Subject is entirely confined to the Instrumental Accompaniment. In 'O God, who from the suckling's mouth,' in the 'Foundling Anthem,' the Melody of 'Aus tiefer Noth' is treated as an orthodox Canto fermo, after the manner of the Motet, 'Ich lasse dich nicht,' already quoted. But, this was not Handel's usual practice. His Canti fermi are more frequently confined to a few notes only of Plain Chaunt, sung slowly, to give weight to the regularly-developed Subject, as in 'Sing ye to the Lord,' the 'Hallelujah Chorus,' the last Chorus in the 'Utrecht Te Deum,' the second in the 'Jubilate,' the Second Chandos Anthem, 'Let God arise,' the last Chorus in 'Esther,' and other places too numerous to mention.[15]

The use of the long-drawn Canto-fermo is fast becoming a lost art; yet the effect with which Mendelssohn has introduced 'Wir glauben all' an einen Gott,' in combination with the primary Subject of 'But our God abideth in Heaven,' in 'S. Paul,' has not often been surpassed. Mozart also has left us a magnificent instance, in the last Finale of 'Die Zauberflöte,' where he has enveloped the Chorale, 'Ach Gott vom Himmel sieh darein,' in an incomparable network of instrumental Counterpoint: and Meyerbeer has introduced two clever and highly effective imitations of the real thing, in 'Les Huguenots,' at the 'Litanies,' and the 'Conjuration.'

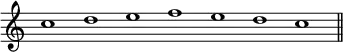

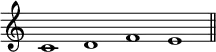

V. The similarity of the Canti fermi, and even of the true Subjects, used by great Composers, and handed on, from generation to generation, has given rise to much ingenious speculation. 1. A remarkable instance of this is a passage of slow notes, rising from the Tonic to the Sub-Dominant, and then descending towards the note from whence it started. This passage is constantly found in old Ecclesiastical Melodies; among others, in that of the Hymn 'Æterna Christi munera.' Zarlino used it as a Theme for his examples in Counterpoint. In Morley's 'Plain and easie Introduction,' Philomathes gives it to Polymathes, as a Point 'familiar enough, and easie to bee maintained'—i.e. developed: while the 'Master' calls it 'a most common Point,' which 'though it were giuen to all the Musicians of the world, they might compose vpon it, and not one of their Compositions bee like vnto that of another.' Byrd used it, in 'Non nobis' [which see]; Palestrina, in the first 'Agnus Dei' of his 'Missa brevis'; Bach, in the 'Gratias agimus' and 'Dona' of his Mass in B minor; Handel, in 'Sing ye to the Lord,' the 'Hallelujah Chorus,' the last Chorus in the 'Utrecht Te Deum,' the Chamber Duet, 'Tacete, ohimè!' and many other places; Steffani, in his Duet, 'Tengo per infallibile '; Perti, in a Fuga à 8, 'Ut nos possimus'; Mendelssohn, in 'Not only unto him,' from 'S. Paul'; and Beethoven, in the Trio of the 9th Symphony. And, in strange contrast to all these grand Compositions, an unknown French Composer used it, with remarkable effect, in 'Malbrook s'en-va-t-en guerre.' The truth is, the passage is simply a fragment of the Scale, which is as much the common property of Musicians, whether Fuguists, or Composers of the later Schools, as the Alphabet is the common property of Poets.[16]

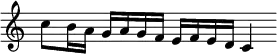

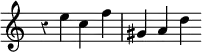

2. Another Subject, scarcely less universal in its application, embraces a more extended portion of the scale. Bach uses this in the 'Weihnachts Oratorium.' Handel, in the 'Hailstone Chorus'; in a remarkable Concerto for two Orchestras, of which the only known copy is the original Autograph at Buckingham Palace; in 'Worthy is the Lamb'; in 'When his loud Voice,' and in many other places. Mozart used it, in a form all but identical with Handel's, and also in the inverted form, in the Jupiter Symphony. Beethoven used it in his First Symphony; in his Sonata, Op. 31. No. 1; and in the inverted form, in his Symphony in C minor. Schumann, in his Stringed Quartet, No. 1, and his PF. Quartet, Op. 47; and Brahms, in the Finale to his Symphony in C Minor.

3. These examples deal only with the Scale. But there are certain progressions which are as much common property as the Scale itself; just as there are certain combinations of letters which are as much common property as the Alphabet. First among these stand the leaps of Fifths or Fourths, with which countless Subjects begin; and scarcely less common are the Sequences of ascending Fourths and descending Fifths, which we so frequently find associated with them: as in Bach's Fugue in E♭ No. 31 of the XLVIII; Mozart's Overture to 'Die Zauberflöte,' and a hundred other cases.

4. Closely allied to these Sequences of Fourths and Fifths, is a form in which a descending Third is followed by an ascending Fourth. This was used for a Canon, by Turini, in the 17th century; in Handel's Second Hautboy Concerto, and third Organ Fugue; Morley's Canzonet, 'Cruel, you pull away too soon'; Purcell's 'Full fathom five'; and numerous other cases, including a Subject given to Mendelssohn for improvisation at Eome, Nov. 23, 1830.

5. A Subject, characterised by the prominent use of a Diminished Seventh, and familiar, as that of 'And with His stripes,' is also a very common one. Handel himself constantly used it as a Theme for improvisation; and other Composers have used it also: notably Mozart, in the Kyrie of the 'Requiem.'

6. The Intonation and Reciting-Note of the Second Gregorian Tone—used either with, or without, the first note of the Mediation—may also be found in an infinity of Subjects, both antient and modern; including that of Bach's Fugue in E, no. 33, and the Finale of the Jupiter Symphony.

The number of Subjects thus traceable from one Composer to another is so great, that it would be impossible to give even a list of them. In fact, as Sir Frederick Ouseley has very justly observed, 'it is perhaps difficult for a Composer of the present day to find a great variety of original Fugue-Subjects.' But, the treatment may be original, though the Subject has been used a thousand times; and these constantly-recurring Subjects are founded upon progressions which, more than any others, suggest new Counter-Subjects in infinite variety.

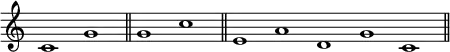

VI. The Subject of Canon differs from that of Fugue, in that it is continuous. The Subject is as long as the Canon itself. Hence, it is called the Guida, or Guide; each note in the leading part directing those that are to be sung by all the other Voices in turn. Subjects of this kind will be found in vol. ii. pp. 228a, 229a, 461b, 464b, 465a, and other places; and many more may be seen in the pages of Burney and Hawkins. Examples of the method of fitting these Subjects together will be found in vol. i. pp. 303b, 304a, and in vol. ii. p. 228b. The number of passages that can be made to fit together in Canon is so limited, that the same notes have been used, over and over again, by writers of all ages. A remarkable instance of this is afforded by 'Non nobis.' We have seen how many Composers have chosen this as a Fugal Subject; and an account of it, with some solutions in Canon not generally known, will be found at vol. ii. p. 464. It must not, however, be supposed that the older Composers alone were able to produce fine Canons. Haydn thoroughly understood the Art of writing them [see vol. i. 710b]; and so graceful are Mozart's that their Subjects might very easily be mistaken for those of an ordinary Part-Song.[17]

VII. Closely allied to the Subject of the Canon is that of the 'Rota,' or Round. In this, and in its comic analogue the Catch, the Guida is followed by every Voice in turn; for which reason the Composition was formerly written on a single Stave. It will be found so written in a facsimile of the oldest example we possess, at page 269 of the present volume: and it is virtually so written, even at the present day; though, in modern copies, the Guida is doubled back, so to speak, each time a new Voice enters, so as to give the outward appearance of a Score. That it is not really a Score is evident, from the fact that there is not a separate Part for each Voice; but, there is a substantial difference between this and the Canon, though the Subject of both is called a Guida. In the Canon, the Subject forms the whole Composition. In the Round, it continues only until the entrance of the second Voice, the later sections of the Guida representing Counter-Subjects only, and continuing to furnish new Counter-Subjects as often as new Voices enter.

It is remarkable that this, the oldest form of sæcular Part-writing in existence, should not only have been invented in England, but should still be more highly esteemed in England than in any other country—for it is only in England that the art of singing a Round is practised with success, and the success with which we practise it dates from the time of the Plantagenets.[18]

VIII. In turning from the learned complexities of Fugue and Canon, to the simple Subject of the Dance-Tune, we are not, as might be supposed, retracing our steps, but following the line traced out for us by the natural development of Art. When Instrumental Music first began to attract attention, the Fugue was regarded as the embodiment of its highest expression. Lulli ended his Overtures with a Fugue; but as time progressed this form of Finale was superseded by that of the Dance-Tune. The most common types were those of the Minuet, the Gavotte, the Bourrée, the Courante, the Chaconne, the Sarabande, the Giga, and the closely allied Tunes of the Allemande, the Ritornello, the Air, and the March. They originally consisted, for the most part, of two short Strains, the first of which stated the Subject, while the second developed it according to its means. It was de rigueur that the Minuet should be written in Triple Time, and that each phrase of its Subject should begin with the down-beat of the bar—though, in later times, most Minuets began with the third beat: that the Gavotte should be in Alla breve Time, beginning at the half-bar: that the Bourrée should be in Common Time, beginning on the fourth beat; that the Allemande should be in Common, and the Giga in Compound Common Time, each beginning, as a general rule, with a single short note: and so with the rest. It was indispensable that the First Strain, representing the Subject, should be complete in itself, though it did not always end in the Key in which it began. The development of the Subject, in the Second Strain, usually consisted in the prolongation of the Melody by means of phrases, which, in the finer examples, were directly derived from itself; sometimes carrying a characteristic figure through two or more closely-related Keys; sometimes returning, after this process, to the initial Strain, and thus completing the symmetry of the Movement in accordance with principles of the deepest artistic significance. The most highly-developed forms were those of the Courante and Allemande. In these, the First Strain, if in the Major Mode, almost invariably modulated to the Dominant, for the purpose of proceeding to a formal close in that Key: if in the Minor Mode, it proceeded, in like manner, to the Relative Major. The Second Strain then started with a tolerably exact reproduction of the initial Subject in the new Key, or some other closely related to it; and the Reprise terminated with the transposition to the original Key of that portion of the First Strain which had first appeared in the Dominant, or Relative Major. In these forms, the share of interest allotted to the process of development was very small indeed, compared with that absorbed by the Subject itself; insomuch that, in many very fine examples, the entire Movement consisted of little more than a Subject artfully extended by the articulation of two members of not very unequal proportions.

IX. Very different from this was the next manifestation of progressive power. Taking the lines of the Allemande as the limit of his general contour, Haydn used a primary Subject, of comparatively limited dimensions, as the foundation of a Movement of greater length and higher development than any previously attempted. For this form a good Subject was of paramount importance; but its office was that of a text, and nothing more: the real interest of the Movement lay in the completeness of its treatment. And, because no form of treatment can be complete without the element of contrast, the Father of the Symphony enriched his new Art-form with a Second Subject, so constructed as to enhance the beauty of the Primary Theme by the introduction of some form of expression distinctly opposed to it. Presented for the first time immediately after the first great Modulation to the Dominant or Relative Major, the subordinate Motive naturally brought the First Section of the Movement to a conclusion, in one or other of those nearly related Keys; and, naturally also, reappeared after the Reprise, with the transposition necessary to terminate the Second Section in the original Key. Haydn sometimes, and Mozart and Beethoven constantly, followed this Second Subject by a Third one, in the same Key—as in the Overture to 'Figaro,' and many similar Movements: but this plan introduced no new principle, and was, in fact, no more than a re-assertion of the leading idea that of introducing a new source of interest at a critical turn of the Movement. With the working of these Subjects we have, at present, no concern. It remains only to show the various forms they assumed in the most important styles of Composition.

In the Overture, the First Subject, if untrammelled by any dramatic or descriptive purpose, is usually a spirited one; and the Second, of a more sustained or cantabile character. In the great majority of cases, both Subjects are complete in themselves; but the first is generally a comparatively short one, while the second sometimes presents the form of a fully-developed Air, consisting of two or even more distinct Strains, as in the Overtures to 'Euryanthe' and 'Ruy Bias.' Very frequently the first forte introduces an independent Theme in the primary Key, as in 'Der Freischütz' and 'A Midsummer Night's Dream.' Classical Overtures almost always start with a strongly marked Theme in Simple Common Time. There is, indeed, no law concerning this point: but the custom is so general, that one of Mendelssohn's most active coadjutors at the Gewandhaus condemned the identity of Time (6-4) in 'The Naiades' and 'The Ruler of the Spirits,' as a self-evident plagiarism on the part of Sterndale Bennett, notwithstanding the entirely different character of the two works. Yet the Overture to 'Egmont' is in 3-4 time.

The First Subject of the Symphony is open to greater variety of character than that of the Overture; is frequently in 3-4 or 6-8 Time, or even in 9-8, as in Spohr's 'Die Weihe der Töne'; and is often of considerable length and extended development, as in Mendelssohn's 'Scotch Symphony.' This last characteristic, however, is by no means a constant one: witness the First Subject, of Beethoven's C minor Symphony, which consists of four notes only. As a general rule, the Second Subject of the Symphony is less extended in form than that of the Overture; and it may be predicated, with almost absolute certainty, that the less extended the Theme, the more completely and ingeniously will it be 'worked,' and vice versa.

The Subjects of the Sonata differ from those of the Symphony chiefly in their adaptation to the distinctive character of the Instrument or Instruments for which they are written; and the same may be said, within certain limits, of those of the Concerto, which however are almost always of greater extension and completeness than those of any other form of Composition, and are treated in a manner peculiar to themselves, and differing very materially, in certain particulars, from the plan pursued in most other Movements—as, for instance, in the almost epigrammatic terseness with which all the Subjects of the First Movement were interwoven, in the opening Tutti, into an epitome of the whole.

But in the important points of completeness and extension, all these Motivi yield to those of the Rondo, the First Subject of which forms a quite independent section of the Movement, and often closes with a definite and well-marked Cadence before the introduction of the first Modulation, as in the Rondo of Beethoven's 'Sonata Pastorale' (op. 29); that of the Sonata in C major (op. 53); that of Mozart's Sonata à 4 mains, in C major; and numerous other instances. This Subject is rarely presented in any other than its original form, in the primitive Key; though, in certain exceptional cases—such as Weber's Rondo for PF. in E♭—it is very elaborately developed. The Second Subject which almost always makes its first appearance in the Key of the Dominant, or Relative Major, to re-appear, after the last Reprise, in the primitive Key—is, in most cases, little less complete and extended than the First, though its construction is generally less homogeneous, consisting, frequently, of two, three, or even more distinct members, marked by considerable diversity of figure and phrasing, as in Weber's Rondo in E♭, already cited. This Subject, like the First, is seldom broken up to any great extent, or very completely 'worked,' though, as we have seen, it is again employed, in its entirety, in a transposed form. The Third Subject is usually of a less extended character than the First and Second; or, if equally complete and continuous, is at least more easily broken up into fragmentary phrases, and therefore more capable of effective working. The Third Subject of Beethoven's 'Sonate Pathétique' (Op. 13), is almost fugal in character, and rendered intensely interesting by its fine contrapuntal treatment, though destined nevermore to re-appear, after the second reprise of the principal Theme. Indeed, each of the three Subjects of the typical Rondo is nearly always so designed as to form the basis of an independent section of the Movement; and, though the First must necessarily appear three, or even four times, in the original Key, and the Second twice, in different Keys, the Third, even when elaborately worked in its own section, is very seldom heard again in a later one. In the Rondo of Beethoven's Sonata, Op. 26, the Third Subject is as complete in itself, and as little dependent on the rest of the Movement, as the Second, or the First; and is summarily dismissed after its first plain statement. But there are, of course, exceptions to this mode of proceeding. In the Rondo of the Sonata in C Major, Op. 53, all the Subjects, including even the First, are worked with an ingenuity quite equal to that displayed in the First Movement of the work. Still, these Subjects all differ entirely, both in form and character, from those employed in the First Movement; and this will always be found to be the case in the Rondos of the great Classical Composers.

There remains yet another class of Subjects to which we have as yet made no allusion, but which, nevertheless, plays a very important part in the œconomy of Musical Composition. We allude to the Subjects of Dramatic Movements, both Vocal and Instrumental. It is obvious, that in Subjects of this kind the most important element is the peculiar form of dramatic expression necessary for each individual Theme. And, because the varieties of dramatic expression are practically innumerable, it is impossible to fix any limit to the varieties of form into which such Subjects may be consistently cast. At certain epochs in the history of the Lyric Drama, consistency has undoubtedly been violated, and legitimate artistic progress seriously hindered, by contracted views on this point. In the days of Hasse, for instance, a persistent determination to cast all Melodies, of whatever character, into the same stereotyped form, led to the petrifaction of all natural expression in the most unnatural of all mechanical contrivances—the so-called 'Concert-Opera.' Against this perversion of dramatic truth all true Artists conscientiously rebelled. Gluck, with a larger Orchestra and stronger Chorus at command, returned to the principles set forth by Peri and Caccini in the year 1600. Mozart invented Subjects, faultlessly proportioned, yet always exactly suited to the character of the dramatic situation, and the peculiar form of passion needed for its expression. These Subjects he wrought into Movements, the symmetry of which equalled that of his most finished Concertos and Symphonies, while their freedom of development, and elaborate construction, not only interposed no hindrance to the most perfect scenic propriety, but, on the contrary, carried on the Action of the Drama with a power which has long been the despair of his most ambitious imitators. Moreover, in his greatest work, 'Il Don Giovanni,' he used the peculiar form of Subject now known as the 'Leading Theme'[19] with unapproachable effect; entrusting to it the responsibility of bringing out the point of deepest interest in the Drama—a duty which it performs with a success too well known to need even a passing comment. In 'Der Freischütz,' Weber followed up this idea with great effect; inventing, among other striking Subjects, two constantly-recurring Themes, which, applied to the Heroine of the piece and the Dæmon, invest the Scenes in which they appear with special interest.

At the present moment, the popularity of the 'Leading Theme' exceeds that of any other kind of Subject; while the danger of relapsing into the dead forms of the School of Hasse has apparently reached its zero. But, the constructive power of Mozart, as exhibited in his wonderful Finales, still sets emulation at defiance.

The different forms of Subject thus rapidly touched upon, constitute but a very small proportion of those in actual use; but we trust that we have said enough to enable the Student to judge for himself as to the characteristics of any others with which he may meet, during the course of his researches, and the more so, since many Subjects of importance are described in the articles on the special forms of Composition to which they belong.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ See Plain-Song.

- ↑ See Hymn.

- ↑ See Antiphon.

- ↑ See Choral.

- ↑ See Strict Counterpoint.

- ↑ See Polyphonia.

- ↑ Published in Breitkopf & Härtel's edition, vol. x.

- ↑ See L'Homme Armé.

- ↑ See Hexachord; Solmisation.

- ↑ See Real Fugue.

- ↑ See Tonal Fugue.

- ↑ See Counter Subject.

- ↑ Ascribed by Schicht and Albrechtsberger to Sebastian Bach; but now more frequently attributed to Johann Christoph. [See vol. i, p. 111a.]

- ↑ 'Thema Legrenzianum pedaliter elaboratum cum subjecto.' The original MS. of this work has disappeared. Messrs. Peters, of Leipzig, have published it in Cahier 4 of their edition of the Organ Works, on the authority of a copy by Andreas Bach.

- ↑ A learned modern critic finds fault with Burney for calling the Canto-fermo in 'Sing ye to the Lord' a Counter-Subject; but falls into the same error himself in describing the Utrecht 'Jubilate.'

- ↑ In the following examples, we give the primary form, only; leaving our readers to compare it, for themselves, with the Compositions to which we have referred.

- ↑ See a large collection of examples in Merrick's English Translation of Albrechtsberger, vol. ii. pp. 415–432.

- ↑ See Schools of Composition, Section XVI; Round; Somer is icumen in.

- ↑ See Leit Motif.