SIGNATURE (Fr. Signes accidentales; Ger. Vorzeichnung, properly regulare Vorzeichnung). The signs of chromatic alteration, sharps or flats, which are placed at the commencement of a composition, immediately after the clef, and which affect all notes of the same names as the degrees upon which they stand, unless their influence is in any case counteracted by a contrary sign.

The necessity for a signature arises from the fact that in modern music every major scale is an exact copy of the scale of C, and every minor scale a copy of A minor, so far as regards the intervals tones and semitones by which the degrees of the scale are separated. This uniformity can only be obtained, in the case of a major scale beginning on any other note than C, by the use of certain sharps or flats; and instead of marking these sharps or flats, which are constantly required, on each recurrence of the notes which require them, after the manner of Accidentals, they are indicated once for all at the beginning of the composition (or, as is customary, at the beginning of every line), for greater convenience of reading. The signature thus shows the key in which the piece is written, for since all those notes which have no sign in the signature are understood to be naturals (naturals not being used in the signature), the whole scale may readily be inferred from the sharps or flats which are present, while if there is no signature the scale is that of C, which consists of naturals only. [See Key.] The following is a table of the signatures of major scales.

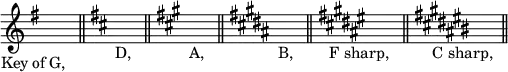

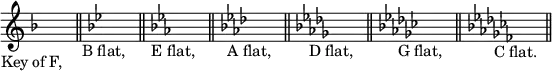

1.

Sharp Signatures.

Flat Signatures.

The order in which the signs are placed in the signature is always that in which they have been successively introduced in the regular formation of scales with more sharps or flats out of those with fewer or none. This will be seen in the above table, where F♯, which was the only of the signature, both in major and minor keys, sharp required to form the scale of G, remains and to mark it as an accidental (like the sharp the first sharp in all the signatures, C♯ being the second throughout, and so on, and the same rule is followed with the flats. The last sharp or flat of any signature is therefore the one which distinguishes it from all scales with fewer signs, and on this account it is known as the essential note of the scale. If a sharp, it is on the seventh degree of the scale; if a flat, on the fourth.

The signature of the minor scale is the same as that if its relative major (i.e. the scale which has its key-note a minor third above the key-note of the minor scale), but the sharp seventh—which, though sometimes subject to alteration for reasons due to the construction of melody is an essential note of the scale—is not included in the signature, but is marked as an accidental when required. The reason of this is that if it were placed there it would interfere with the regular order of sharps or flats, and the appearance of the signature would become so anomalous as to give rise to possible misunderstanding, as will be seen from the following example, where the signature of A minor (with sharp seventh) might easily be mistaken for that of G major misprinted, and that of F minor for E♭ major.

In former times many composers were accustomed to dispense with the last sharp or flat of the signature, both in major and minor keys, and to marke it as an accidental (like the sharp seventh of the minor scale) wherever required, possibly in order call attention to its importance as an essential note of the scale. [App. p.793 "The true explanation of the omission of the last flat or sharp from the signature referred to on p. 493b, is probably to be found in the influence of the ancient modes."] Thus Handel rarely wrote F minor with more than three flats, the D♭ being marked as an accidental as well as the E♮ (see 'And with His stripes' from Messiah); and a duet 'Joys in gentle train appearing' (Athalia), which is in reality in E major, has but three sharps. Similar instances may be found in the works of Corelli, Geminiani, and others.

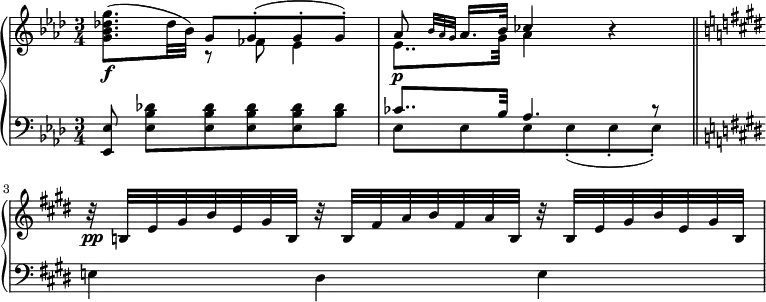

When in the course of a composition the key changes for any considerable period of time, it is frequently convenient to change the signature, in order to avoid the use of many accidentals. In effecting this change, such sharps or flats as are no longer required are cancelled by naturals, and this is the only case in which naturals are employed in the signature; for example—

3.

Hummel, 'La Contemplazione.'

[ F. T. ]