SEQUENCE is generally taken to mean the repetition of a definite group of notes or chords in different positions of the scale, like regular steps ascending or descending, as in the following outlines:—

![{ \new Staff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/2 \partial 2

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemUp

\[ c2^"1." | a \] d | b e | c f | d g | e1 \bar "||" }

\new Voice \relative c' { \stemDown

c2 | f d | g e | a f | b g | c1 } >> }](../../I/561645f3dc5a071a27027d02ea757232.png.webp)

![{ \new Staff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/2 \partial 1.

\new Voice \relative g'' { \stemUp

\[ g2^"2." f d | e \] f e c | d e d b | c d c a | b1 \bar "||" }

\new Voice \relative g' { \stemDown

g2 a b | c f, g a | b e, f g | a d, e f | g1 } >> }](../../I/c177ebc50479a45dac72b12a8121dbc6.png.webp)

The device has been a favourite one with composers, from Corelli, Bach, and Handel, to Schumann, Brahms, and Wagner. The reason is partly that it is so thoroughly intelligible without being commonplace. The mind is easily led from point to point by recognising each successive step after the first group of chords has been given, and is sufficiently interested by the slight amount of diversity which prevails at each repetition. It thus supplies a vital element of form in a manner which in some cases has certain advantages over simple exact repetition, especially when short phrases are repeated in juxtaposition. It was consequently made much use of by early composers of sonatas, and instrumental works of like nature, such as Corelli and his immediate successors; and in many cases examples make their appearance at analogous points in different movements, indicating the recognition of formal principles in their introduction. This occurs, for instance, near the beginning of the second half in the following movements from Corelli's Opera Quarta: Corrente and Allemanda of Sonata 1, Allemanda and Corrente of Sonata 2, Corrente of Sonata 3, Corrente and Giga of Sonata 4, Gavotte of Sonata 5, Allemanda and Giga of Sonata 6, and so forth. A large proportion of both ancient and modern sequences are diatonic; that is, the groups are repeated analogously in the same key series, without consideration of the real difference of quality in the intervals; so that major sevenths occasionally answer minor sevenths, and diminished fifths perfect fifths, and so forth; and it has long been considered allowable to introduce intervals and combinations in those circumstances which would otherwise have been held inadmissible. Thus a triad on the leading note would in ordinary circumstances be considered as a discord, and would be limited in progression accordingly; but if it occurred in a sequence, its limitations were freely obviated by the preponderant influence of the established form of motion. Such diatonic sequences, called also sometimes diatonic successions, are extremely familiar in Handel's works. A typical instance is a Capriccio in G major, published in Pauer's 'Alte Meister,' which contains at least fifteen sequences, some of them unusually long ones, in four pages of Allegro. The subject itself is a characteristic example of a sequence in a single part; it is as follows:—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4 \key g \major \relative d'' {

r16 \[ d c d b d g, b e, \] c' b c a c fis, a |

d, b' a b g b e, g c,8 a' g a | fis s_"etc." } }](../../I/abfb469b8f1298f4348880f73d0cb788.png.webp)

A kind of sequence which was early developed, but which is more characteristic of later music, is the modulatory sequence, sometimes also called chromatic. In this form accidentals are introduced, sometimes by following exactly the quality of the intervals where the diatonic series would not admit of them, and sometimes by purposely altering them to gain the step of modulation. This will be easily intelligible from the following example:—

![{ \new Staff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4

\new Voice \relative e'' { \stemUp

\[ e4 d8 b c4 \] | d c8 a b4 |

c bes8 g a4 | b! a8 fis g4 \bar "||" }

\new Voice \relative e' { \stemDown

e4 gis a | d, fis g! | c, e f | b,! dis e } >> }](../../I/15a4e96ea38e8cb7262593455c8b24ca.png.webp)

The usefulness of the device in such circumstances is, if anything, even more marked than it is in a single key, because of the greater breadth of range which it allows, and the closeness and cogency of the successive transitions which it renders possible. A compact and significant example to the point is the following from a fugue by Cherubini in C major:—

Beethoven made very remarkable use of this device, especially in the great Sonata in B♭, op. 106, from which an example is quoted in the article Modulation. [See ii. 350.] The 'working out' portion of the first movement of the same sonata is an almost unbroken series of sequences of both orders; and the introduction to the final fugue is even more remarkable, both for the length of the sequence, and the originality of its treatment. The first-mentioned, which is from the Slow Movement, is further remarkable as an example of a peculiar manipulation of the device by which modern composers have obtained very impressive results. This is the change of emphasis in the successive steps of which it is composed. For instance, if the characteristic group consists of three chords of equal length, and the time in which it occurs is a square one, it is clear that the chord which is emphatic in the first step will be weakest in the next, and vice versâ. This form will be most easily understood from an outline example:—

![{ \new Staff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemUp

\[ c4 b a \] d | c b e d | c f e d | g f e }

\new Voice \relative c' { \stemDown

c4 e f d | f g e g | a f a b | g f c } >> }](../../I/355406df08b379b3bf1e14df87a52e1e.png.webp)

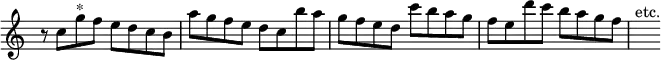

A passage at the beginning of the Presto at the end of Beethoven's Leonora Overture, No. 3, is a good example of a sequence of this kind in a single part. It begins in the following quotation at *

The extension of the characteristic group of a sequence is almost unlimited, but it will be obvious at once that in harmonic sequences the shorter and simpler they are the more immediately they will be understood. In long-limbed sequences the hearer may soon perceive that there is a principle of order underlying what he hears, though its exact nature may always elude his apprehension, and in respect of the larger branches of form this is a decided advantage. Among short-limbed emphatic sequences in modern music, the one of eight steps which occurs towards the end of the first full portion of the Overture to the Meistersinger is conspicuous, and it has the advantage of being slightly irregular. The long-limbed sequences are sometimes elaborately concealed, so that the underlying source of order in the progression can only with difficulty be unravelled. A remarkable example of a very complicated sequence of this kind is a passage in Schumann's Fantasia in C major (op. 17), in the movement in E♭, marked 'Moderate con energia,' beginning at the 58th bar. The passage is too long to quote, but the clue to the mystery may be extracted somewhat after this manner:—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\time 4/4 \key ees \major \relative a {

r4 \[ a d c | bes f'2 bes,4 | b f'2 b,4 | c f d f |

ees \] \clef bass g, c bes | %end line 1

aes ees'2 aes,4 | a ees'2 a,4 | bes ees c d |

bes \clef treble d g f | ees bes'2 ees,4 | %end line 2

e bes'2 e,4 | f bes g bes | aes8 s_"etc." } }](../../I/61c6699dffb7f0398a6c8ed2c47c429a.png.webp)

In order to see how this has been manipulated reference must be made to the original.

A species of sequence which is familiar in modern music is that in which a figure or melody is repeated a tone higher; this has been termed a Rosalia. [See vol. iii, p. 160.] Another, which is equally characteristic, is a repetition of a figure or passage a semitone higher; an example from the Eroica Symphony is quoted in vol. ii. p. 346 of this Dictionary.

The device has never been bound to rigid exactness, because it is easy to follow, and slight deviations seasonably introduced are often happy in effect. In fact its virtue does not consist so much in the exactness of transposition as in the intelligibility of analogous repetitions. If the musical idea is sufficiently interesting to carry the attention with it, the sequence will perform its function adequately even if it be slightly irregular both in its harmonic steps and in its melodic features; and this happens to be the case both in the example from the Slow Movement of Beethoven's Sonata in B♭, and in the passage quoted from Schumann's Fantasia. It is not so, however, with the crude harmonic successions which are more commonly met with; for they are like diagrams, and if they are not exact they are good for nothing.[ C. H. H. P. ]