SCHERZO. An Italian word signifying 'jest' or 'joke.' Its application in music is extensive, and—as is the case with many other musical titles—often incorrect. Most of the movements, from the time of Mendelssohn onwards, would be better designated as 'Caprices' or 'Capriccios.' Obviously the word signifies that the piece to which it applies is not merely of a light and gay character, but is of the nature of a joke, in that it possesses that rare quality in music, humour. But, exclusive of Haydn and Beethoven, what musician shows humour, real unaffected drollery, in his music?

The term seems to have been first employed (Scherzando) merely as a direction for performance, but there are early instances of its use as a distinctive title. The light Italian canzonets popular in Germany in the 17th century were called Scherzi musicali. In 1688 Johann Schenk published some 'Scherzi musicali per la viola di gamba.' Later, when each movement of an instrumental composition had to receive a distinctive character, the directions Allegretto scherzando and Presto scherzando became common, several examples occurring in the Sonatas of Ph. Em. Bach. But even in the 'Partitas' of his great father, we find a Scherzo preceded by a Burlesca and a Fantaisie, though few modern ears can discover anything of humour or fancy in either of these. The Scherzo commences

and might as well have been termed a Gavotte. There is another Scherzo among the doubtful works beginning thus:

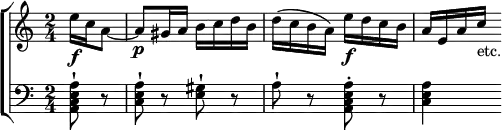

Many of the Gigues are far more frolicsome than these would-be jests. In Peters's edition of Scarlatti's Clavecin pieces, will be found a piece with the following theme for principal subject, which the editor, von Bülow, has entitled a Scherzo:

The initial figure of this theme, treated in free imitation, runs through the movement. As a similar phrase forms so distinctive a feature of the Scherzo to Beethoven's 7th Symphony it is not unfair to compare the two, and remark the difference between a merely bright little piece with no particular qualities, and a true Scherzo which fills the heart with lively and delightful thoughts. In the same volume will be found a Capriccio (No. 4) which is a real Scherzo in all but name.

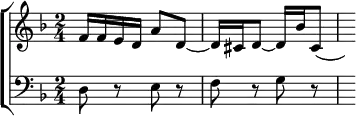

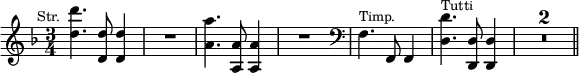

Coming now to the period of the Symphony it may be as well to remind the reader of a fact which will be more enlarged upon under that heading, namely, that the presence of the Minuet or Scherzo in works of the symphonic class, is a matter of natural selection, or survival of the fittest. In the old Suites the Minuet, being of rather shorter rhythm than the other dances, was seized upon, perhaps unconsciously, by the great masters who tied themselves down to the old form, and was exaggerated out of all recognition for the sake of contrast. The actual Minuet, as danced from the 16th century up to the present day (if any one still learns it), is in the time of that famous specimen in Mozart's Don Juan, or say M. M. ♩ = 80. Yet even in the Suites of Bach one finds quick and slow Minuets, neither having any regard to the requirements of the dance. When we come to Haydn the term Minuet ceases to have any meaning; the stateliness and character of the dance are quite gone, and what we should call a Waltz appears. But with the true instinct of an artist, Haydn felt that in a work containing such heavy subtleties (for even Haydn was deemed heavy and subtle once) as the ordinary first movement and slow movement, a piece of far lighter character was imperatively demanded. So lighter and quicker and more sportive grew the Minuets, till Beethoven crowned the incongruous fashion with the 'Minuet' of his 1st Symphony. It should be mentioned, however, that Mozart never departed nearly so far from the true Minuet as Haydn, whose gaiety of musical thought drove him into really inventing the Scherzo, though he did not use the name. The Minuets of many of the String Quartets of Haydn exhibit indeed those quaint and fanciful devices of unexpected reiteration, surprises of rhythm, and abrupt terminations, which are the leading characteristics of the Scherzo, and are completely opposed to the spirit of the true Minuet. One which begins and ends each part with these bars

is a strong instance in point.

Beethoven quickly gave the Scherzo the permanent position in the Symphony which it now occupies. He also settled its form and character. As to form, why, the old Minuet and Trio was as good a skeleton as any other; for what matters the shape of the bones when we are dazzled by the form which covers them? It is a good answer to those who consider the classical forms worn out and irksome to the flow of inspiration to point out that in the Scherzo, where full rein is given to the individual caprice of the musician, there is as much attention given to construction as anywhere. In fact, either the bold and masculine First-movement form, or its sister, the weaker and more feminine Rondo form must be the backbone of every piece of music with any pretensions to the name. But, lest the light and airy character of the Scherzo should be spoilt by the obtrusion of the machinery, the greater composers have sought to obscure the form artistically by several devices, the most frequent and obvious being the humorous persistent dwelling on some one phrase—generally the leading feature of the first subject—and introducing it in and out of season, mixed up with any or all of the other subjects. Witness the Scherzo of Beethoven's 9th Symphony, quoted below, where the opening phrase is used as an accompaniment to the 2nd subject—indeed as a persistent 'motto' throughout. Apart from this there is not the slightest departure from rigid First-movement form in this great movement.

The Trio, which is a relic of the Minuet and takes the position of third subject or middle section in a Rondo, survives because of the naturally felt want of a contrast to the rapid rhythm of the Scherzo. Many modern composers affect to dispense with it, but there is usually a central section answering to it, even though it be not divided off from the rest by a double bar. Mendelssohn has been the most successful in writing Scherzos without Trios. The main idea was to have a movement in extremely short and marked rhythm, for which purpose triple time is of course the best. In the Pianoforte Sonatas the Scherzo to that in E♭ (Op. 31, No. 3) is the only instance where Beethoven has employed 2–4. The Trios to the Scherzos of the Pastoral and Choral Symphonies are 2–4 and ![]() for special reasons of effect and contrast. It may be worth noticing that Beethoven invariably writes 3–4 even where 6–8 or 3–8 could equally well have been employed. This is no doubt in order that the written notes should appeal to the eye as much as the sounded notes to the ear. In fact three crotchets, with their separate stems, impress far more vividly on the mind of the player the composer's idea of tripping lightness and quick rhythm than three quavers with united tails. Having once ousted the Minuet, Beethoven seldom re-introduced it, the instances in which he has done so being all very striking, and showing that a particularly fine idea drove him to use a worn-out means of expression. In several cases (PF. Sonatas in E♭, op. 7; in F, op. 10, etc.) where there is no element of humour he has abstained from the idle mockery of calling the movement a Minuet, because it is not a Scherzo, as others have done; yet, on the other hand, the third movements of both the 1st, 4th, and 8th Symphonies are called Minuets while having little or nothing in common with even the Symphony Minuets of Haydn and Mozart. Amongst Beethoven's endless devices for novelty should be noticed the famous treatment of the Scherzo in the C minor Symphony; its conversion into a weird and mysterious terror, and its sudden reappearance, all alive and well again, in the midst of the tremendous jubilation of the Finale. Symphony No. 8, too, presents some singular features. The second movement is positively a cross between a slow movement and a Scherzo, partaking equally of the sentimental and the humorous. But the Finale is nothing else than a rollicking Scherzo, teeming with eccentricities and practical jokes from beginning to end, the opening jest (and secret of the movement) being the sudden unexpected entry of the basses with a tremendous C sharp, afterwards turned into D flat, and the final one, the repetition of the chord of F at great length as if for a conclusion, and then, when the hearer naturally thinks that the end is reached, a start off in another direction with a new coda and wind-up.

for special reasons of effect and contrast. It may be worth noticing that Beethoven invariably writes 3–4 even where 6–8 or 3–8 could equally well have been employed. This is no doubt in order that the written notes should appeal to the eye as much as the sounded notes to the ear. In fact three crotchets, with their separate stems, impress far more vividly on the mind of the player the composer's idea of tripping lightness and quick rhythm than three quavers with united tails. Having once ousted the Minuet, Beethoven seldom re-introduced it, the instances in which he has done so being all very striking, and showing that a particularly fine idea drove him to use a worn-out means of expression. In several cases (PF. Sonatas in E♭, op. 7; in F, op. 10, etc.) where there is no element of humour he has abstained from the idle mockery of calling the movement a Minuet, because it is not a Scherzo, as others have done; yet, on the other hand, the third movements of both the 1st, 4th, and 8th Symphonies are called Minuets while having little or nothing in common with even the Symphony Minuets of Haydn and Mozart. Amongst Beethoven's endless devices for novelty should be noticed the famous treatment of the Scherzo in the C minor Symphony; its conversion into a weird and mysterious terror, and its sudden reappearance, all alive and well again, in the midst of the tremendous jubilation of the Finale. Symphony No. 8, too, presents some singular features. The second movement is positively a cross between a slow movement and a Scherzo, partaking equally of the sentimental and the humorous. But the Finale is nothing else than a rollicking Scherzo, teeming with eccentricities and practical jokes from beginning to end, the opening jest (and secret of the movement) being the sudden unexpected entry of the basses with a tremendous C sharp, afterwards turned into D flat, and the final one, the repetition of the chord of F at great length as if for a conclusion, and then, when the hearer naturally thinks that the end is reached, a start off in another direction with a new coda and wind-up.

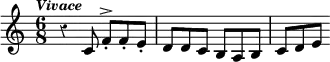

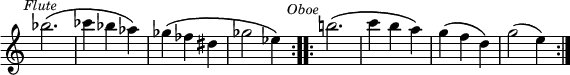

As a specimen of true Scherzo—that is, a movement in strict form and with quaint and whimsical humorous devices springing up unexpectedly, but naturally, throughout,—the Scherzo of the 9th Symphony must ever stand without a rival. The tiny phrase which is the nucleus of the whole is thus eccentrically introduced:—

preparing us at the outset for all manner of starts and surprises. The idea of using the drums for this phrase seems to have tickled Beethoven's fancy, as he repeats it again and again.

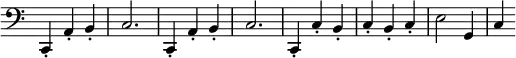

Humour is more unexpected in Schubert than in Beethoven, and perhaps because of its unexpectedness we appreciate it the more. The Scherzo of the C major Symphony is full of happy thoughts and surprises, as fine as any of Beethoven's, and yet distinct from them. The varied changes of rhythm in 2, 3 and 4 bars, the piquant use of the wood wind, and above all the sudden and lovely gleam of sunshine—

combine to place this movement among the things imperishable. The Scherzos of the Octet, the Quintet in C, and above all, the PF. Duet in C, which Joachim has restored to its rightful dignity of Symphony, are all worthy of honour. The last-named, with its imitations by inversion of the leading phrase, and its grotesque bass

is truly comical.

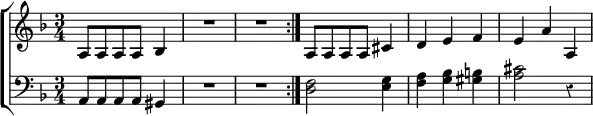

It is much to be regretted that the more modern composers have lost sight of the true bearing of the Scherzo so completely. Mendelssohn indeed has given it an elfish fairy character, but though this is admirable in the 'Midsummer Night's Dream,' it is perhaps a little out of place elsewhere. Lightness and airy grace his Scherzos possess to admiration, in common with his Capriccios, which they closely resemble; but the musical humour which vents itself in unexpected rhythms and impudent upstartings of themes in strange places, neither he nor any later composer seems to have had an idea of. Mendelssohn has not used the title 'Scherzo' to either of his five symphonies, though the 'Vivace non troppo' of the Scotch, the 'Allegretto' of the Lobgesang, and the 'Allegro Vivace' of the Reformation are usually called Scherzos. It is sufficient to name the String Octet, the two PF. Trios and the two Quintets for Strings, as a few of his works which contain the most striking specimens in this line. As before mentioned, his Capriccios for Piano are pieces of the same order, and No. 4 of the 'Sieben Charakter-stücke' (op. 7) may be classed with them.

With Schumann we find ourselves again in a new field. Humour, his music seldom, if ever, presents, and he is really often far less gay in his Scherzos than elsewhere. He introduced the innovation of two Trios in his B♭ and C Symphonies, PF. Quintet, and other works, but although this practice allows more scope to the fancy of the composer in setting forth strongly contrasted movements in related rhythm, it is to be deprecated as tending to give undue length and consequent heaviness to what should be the lightest and most epigrammatic of music. Beethoven has repeated the Trios of his 4th and 7th Symphonies, but that is quite another thing. Still, though Schumann's Scherzos are wanting in lightness, their originality is more than compensation. The Scherzos of his orchestral works suffer also from heavy and sometimes unskilful instrumentation, but in idea and treatment are full of charm. Several of his Kreisleriana and other small PF. pieces, are to all intents and purposes Scherzos.

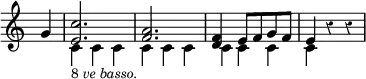

Though the modern composers have not produced many remarkable Scherzos, it is not for want of trying. Rubinstein has a very pretty idea in 6–4 time in his Pianoforte Octet, and a very odd one in his A major Trio. The 'Ocean' Symphony has two Scherzos, in excellent contrast, the first being in 2–4 time, and slightly Schumannish, and the second in 3–4 time, with quite a Beethoven flavour. The first of these is not, however, entitled Scherzo by the composer any more than is the second movement of his 'Dramatic' Symphony, which begins with the following really humorous idea:—

Raff has—as frequently in other cases—spoilt many fine ideas by extravagances of harmony and lack of refinement. The two PF. Quartets (op. 202) show him at his very best in Scherzo, while his wonderful and undeservedly neglected Violin Sonatas have two eccentric specimens. The 1st Sonata (E minor, op. 73) has a Scherzo with bars of 2, 3, 4, and 5 crotchets at random; thus:—

![\relative e'' { \time 3/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \mark \markup \small "3" \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

e4 dis8( e) e4 | dis8( e) e4 dis8( e) | \time 5/4 \mark \markup \small "5"

e[( f)] f[( cis)] cis[( d)] d[( a')] a[( dis,)] | \break \time 4/4 \mark \markup \small "4"

dis[( e)] e[( g]) g[( c]) c[( b)] | b[( a)] a[( g)] g[( f)] f[( dis)] \time 2/4 \mark \markup \small "2" dis[( e)] e[( f)] }](../../I/76b5dcfb76a73abf4f5b78a78d696345.png.webp)

while the Trio, which is in 3–4 time, is played so tempo rubato as to appear equally timeless with the above. In the Scherzo of the 2nd Sonata (A major, op. 78) occurs an odd effect. For no less than 56 bars the Violin sustains its low G as a pedal, while continuing a bagpipe melody against brilliant running accompaniment. In the Symphonies the 'Dance of Dryads' of the 'Im Walde' is perhaps the best Scherzo, most of the others being too bizarre and artificial.

Unlike Schubert and Beethoven, Brahms seldom rises sufficiently from his natural earnestness to write a really bright Scherzo, but he has published one for PF. solo (op. 4) which is very odd and striking. The 2nd Symphony has a movement which is a combination of Minuet and Scherzo, and certainly one of his most charming ideas. On somewhat the same principle is the Scherzo of the 2nd String Sextet (op. 36) which begins in 2–4 as a kind of Gavotte, while the Trio is 3–4 Presto, thus reversing the ordinary practice of making the Trio broader and slower than the rest of the piece.

Quite on a pedestal of their own stand the four Scherzos for piano by Chopin. They are indeed no joke in any sense; the first has been entitled 'Le Banquet infernal,' and all four are characterised by a wild power and grandeur which their composer seldom attained to.

Among recent productions may be noticed the Scherzo for orchestra by Goldmark, the so-called Intermezzo of Goetz's Symphony, the Scherzos in Dvorak's Sextet, and other chamber works. We have omitted mention of the strangely instrumented 'Queen Mab' Scherzo of Berlioz—more of a joke in orchestration than anything.

The position of the Scherzo in the Symphony—whether second or third of the four movements—is clearly a matter of individual taste, the sole object being contrast. Beethoven, in the large majority of cases, places it third, as affording relief from his mighty slow movements, whereas most modern composers incline to place it as a contrast between the first and slow movements. The matter is purely arbitrary.[ F. C. ]