REQUIEM (Lat. Missa pro Defunctis; Ital. Messa per i Defonti; Fr. Messe des Morts; Germ. Todtenmesse). A solemn Mass, sung, annually, in Commemoration of the Faithful Departed, on All Souls' Day (Nov. 2); and, with a less general intention, at Funeral Services, on the anniversaries of the decease of particular persons, and on such other occasions as may be dictated by feelings of public respect, or individual piety.

The Requiem takes its name[1] from the first word of the Introit—'Requiem æternam dona eis, Domine.' When set to Music, it naturally aranges itself in nine principal sections: (1) The Introit—'Requiem æternam'; (2) the 'Kyrie'; (3) the Gradual, and Tract—'Requiem æternam,' and 'Absolve, Domine'; (4) The Sequence or Prose—'Dies iræ'; (5) The Offertorium—'Domine Jesu Christi'; (6) the 'Sanctus'; (7) the 'Benedictus'; (8) the 'Agnus Dei'; and (9) the Communio—'Lux æterna.' To these are sometimes added (10) the Responsorium, 'Libera me,' which, though not an integral portion of the Mass, immediately follows it, on all solemn occasions; and (11) the Lectio'—Tædet animam meam,' of which we possess at least one example of great historical interest.

The Plain Chaunt Melodies adapted to the nine divisions of the Mass will be found in the Gradual; together with that proper for the Responsorium. The Lectio, which really belongs to a different Service, has no proper Melody, but is sung to the ordinary 'Tonus Lectionis.' [See Accents.] The entire series of Melodies is of rare beauty; and produces so solemn an effect, when sung, in Unison, by a large body of Grave Equal Voices, that most of the great Polyphonic Composers have employed its phrases more freely than usual, in their Requiem Masses, either as Canti fermi, or, in the form of unisonous passages interposed between the harmonised portions of the work. Compositions of this kind are not very numerous; but most of the examples we possess must be classed among the most perfect productions of their respective authors.

Palestrina's 'Missa pro Defunctis,' for 5 Voices, first printed at Rome in 1591, in the form of a supplement to the Third Edition of his 'First Book of Masses,' was reproduced in 1841 by Alfieri, in the first volume of his 'Raccolta di Musica Sacra'; again, by Lafage, in a valuable 8vo. volume, entitled 'Cinq Messes de Palestrina';[2] and by the Prince de la Moskowa in the 9th volume of his collection [see p. 31 of the present vol.], and has since been advertised, by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel, of Leipzig, as part of the contents of their complete edition. This beautiful work is, unhappily, very incomplete, consisting only of the 'Kyrie,' the 'Offertorium,' the 'Sanctus,' the 'Benedictus,' and the 'Agnus Dei.' We must not, however, suppose that the Composer left his work unfinished. It was clearly his intention that the remaining Movements should be sung, in accordance with a custom still common at Roman Funerals, in unisonous Plain Chaunt: and, as a fitting conclusion to the whole, he has left us two settings of the 'Libera me,' in both of which the Gregorian Melody is treated with an indescribable intensity of pathos.[3] One of these is preserved, in MS., among the Archives of the Pontifical Chapel, and the other, among those of the Lateran Basilica. After a careful comparison of the two, Baini arrived at the conclusion that that belonging to the Sistine Chapel must have been composed very nearly at the same time as, and probably as an adjunct to, the five printed Movements, which are also founded, more or less closely, upon the original Canti fermi, and so constructed as to bring their characteristic beauties into the highest possible relief—in no case, perhaps, with more touching effect than in the opening 'Kyrie,' the first few bars of which will be found at page 78 of our second volume.

Next in importance to Palestrina's Requiem, is a very grand one, for 6 Voices, composed by Vittoria, for the Funeral of the Empress Maria, widow of Maximilian II. This fine work—undoubtedly the greatest triumph of Vittoria's genius—comprises all the chief divisions of the Mass, except the Sequence, together with the Responsorium, and Lectio; and brings the Plain Chaunt Subjects into prominent relief, throughout. It was first published, at Madrid, in 1605—the year of its production. In 1869 the Lectio was reprinted at Ratisbon, by Joseph Schrems, in continuation of Proske's 'Musica divina.' A later cahier of the same valuable collection contains the Mass and Responsorium; both edited by Haberl, with a conscientious care which would leave nothing to be desired, were it not for the altogether needless transposition with which the work is disfigured, from beginning to end. The original volume contains one more Movement—'Versa est in luctum'—which has never been reproduced in modern notation; but, as this has now no place in the Roman Funeral Service, its omission is not so much to be regretted.

Some other very fine Masses for the Dead, by Francesco Anerio, Orazio Vecchi, and Giov. Matt. Asola, are included in the same collection, together with a somewhat pretentious work, by Pitoni, which scarcely deserves the enthusiastic eulogium bestowed upon it by Dr. Proske. A far finer Composition, of nearly similar date, is Colonna's massive Requiem for 8 Voices, first printed at Bologna in 1684—a copy of which is preserved in the Library of the Sacred Harmonic Society.

Our répertoire of modern Requiem Masses, if not numerically rich, is sufficiently so, in quality, to satisfy the most exacting critic. Three only of its treasures have attained a deathless reputation; but, these are of such superlative excellence, that they may be fairly cited as examples of the nearest approach to sublimity of style that the 19th century has as yet produced.

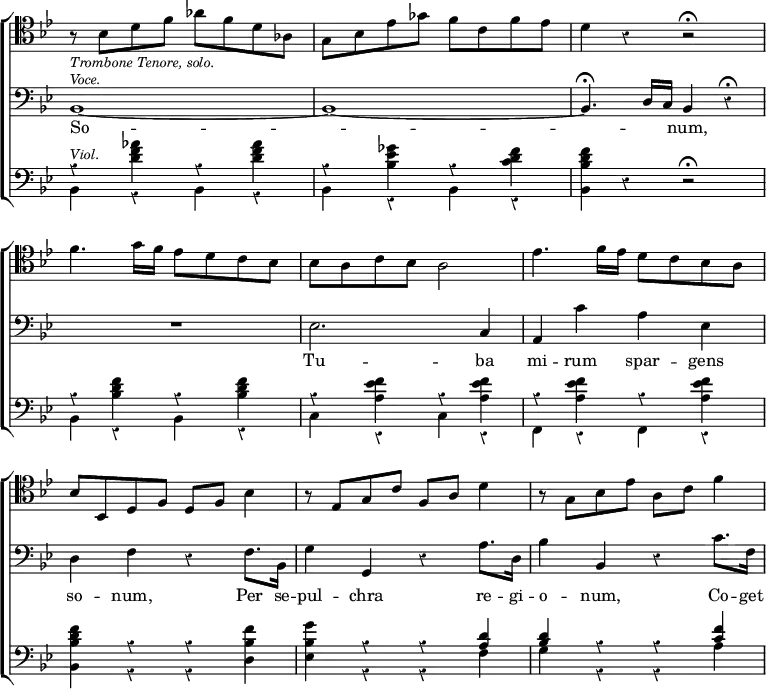

(1.) The history of Mozart's last work is surrounded by mysteries which render it scarcely less interesting to the general reader than the Music itself is to the student. Thanks to the attention drawn to it by recent writers, the narrative is now so well known, that it is needless to do more than allude to those portions of it which tend to assist the critic in his analysis of the Composition. Its outline is simple enough. In the month of July, 1791, Mozart was commissioned to write a Requiem, by a mysterious looking individual, whom, in the weakness consequent upon his failing health and long-continued anxiety, he mistook for a visitant from the other world. It is, now, well known that the 'Stranger' was, really, a certain Herr Leutgeb, steward to Graf Franz von Walsegg, a nobleman residing at Stuppach, who, having lately lost his wife, proposed to honour her memory by foisting upon the world, as his own Composition, the finest Funeral Mass his money could procure. This, however, did not transpire until long after Mozart's death. Suspecting no dishonourable intention on the part of his visitor, he accepted the commission; and strove to execute it, with a zeal so far beyond his strength, that worn out with over-work and anxieties, and tormented by the idea that he was writing the Music for his own Funeral, he died while the MS. still remained unfinished. His widow, fearing that she might be compelled to refund the money already paid for the work in advance, determined to furnish the 'Stranger' with a perfect copy, at any risk; and, in the hope of accomplishing this desperate purpose, entrusted the MS., first, to the Hofkapellmeister, Jos. von Eybler, and afterwards to Franz Xavier Süssmayer, for completion. Von Eybler, after a few weak attempts, gave up the task in despair. Süssmayer was more fortunate. He had watched the progress of the Requiem through each successive stage of its development. Mozart had played its various Movements to him on the Pianoforte, had sung them with him over and over again, and had even imparted to him his latest ideas on the subject, a few hours, only, before his death. Süssmayer was an accomplished Musician, intimately acquainted with Mozart's method of working: and it would have been hard, if, after having been thus unreservedly admitted into the dying Composer's confidence, he had been unable to fill up his unfinished sketches with sufficient closeness of imitation to set the widow's fears of detection at rest. He did in fact, place in her hands a complete Requiem, which Count Walsegg accepted, in the full belief that it was in Mozart's handwriting throughout. The 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie' were really written by Mozart; but the remainder was skilfully copied from sketches—now generally known as the 'Urschriften'—which, everywhere more or less unfinished, were carefully filled in, as nearly as possible in accordance with the Composer's original intention. The widow kept a transcript of this MS., and afterwards sold it to Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel, of Leipzig, who printed it, in full score, in 1800. But, notwithstanding the secrecy with which the affair had been conducted, rumours were already afloat, calculated to throw grave doubts upon the authenticity of the work. Süssmayer, in reply to a communication addressed to him by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel, laid claim to the completion of the 'Requiem,' 'Kyrie,' 'Dies iræ,' and 'Domine,'—of which he said that Mozart had 'fully completed the four Vocal Parts, and the Fundamental Bass, with the Figuring, but only here and there indicated the motivi for the Instrumentation,'—and asserted that the 'SaNctus,' 'Benedictus,' and 'Agnus Dei,' were entirely composed by himself (ganz neu, von mir verfertigt). This bold statement, however, did not set the dispute at rest. It was many times revived, with more or less acerbity; until, in 1825, Gottfried Weber brought matters to a climax, by publishing a virulent attack upon the Requiem, which he denounced as altogether unworthy of Mozart, and attributed almost entirely to Süssmayer. To follow the ensuing controversy through its endless ramifications would far exceed our present limits. Suffice it to say, that we are now in possession of all the evidence, documentary or otherwise, which seems at all likely to be brought forward on either side. With the assistance of Mozart's widow (then Madame von Nissen), Joh. André, of Offenbach, published, in 1826, a new edition of the Score, based upon that previously printed by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel, but corrected, by careful comparison, in the presence of the Abbé Stadler, with that originally furnished to the Graf von Walsegg, and marked, on the Abbé's authority, with the letters, 'M.' and 'S.' to distinguish the parts composed by Mozart from those added by Süssmayer. In 1829, Herr André conferred another benefit upon the artistic world by publishing, with the widow's permission, Mozart's original sketches of the 'Dies iræ,' 'Tuba mirum,' and 'Hostias,' exactly as the Composer left them. All these publications are still in print, together with another Score, lately published by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel in their complete edition of Mozart, in which the distinction between Mozart's work and Süssmayer's is very clearly indicated, as in Andre's earlier edition, by the letters 'M.' and 'S.' Happily, the original MSS. are now in safe keeping, also. In 1834, the Abbé Stadler bequeathed the autograph sketch of the entire 'Dies iræ,' with the exception of the last Movement, to the Imperial Library at Vienna. Hofkapellmeister von Eybler soon afterwards presented the corresponding MSS. of the 'Lacrymosa,' the 'Domine Jesu,' and the 'Hostias.' The collection of 'Urschriften,' therefore, needed only the original autographs of the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' to render it complete. These MSS, alone, would have been a priceless acquisition; but, in 1838, the same Library was still farther enriched by the purchase, for 50 ducats, of the complete MS. originally sold to Count von Walsegg; and it is now conclusively proved that the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' with which this MS. begins, are the original autographs needed to complete the collection of 'Urschriften'; and, that the remainder of the work is entirely in the hand-writing of Süssmayer. It is, therefore, quite certain, that, whatever else he may have effected, Süssmayer did not furnish the Instrumentation of the 'Requiem' and 'Kyrie,' as he claims to have done.[4]

In criticising the merits of the Requiem as a work of Art, it is necessary to weigh the import of these now well-ascertained facts, very carefully indeed, against the internal evidence afforded by the Score itself. The strength of this evidence has not, we think, received, as yet, full recognition. Gottfried Weber, dazzled, perhaps, by the hypothetic excellence of another Requiem of his own production, roundly abused the entire Composition, which he described as a disgrace to the name of Mozart. Few other Musicians would venture to adopt this view; though many have taken exception to certain features in the Instrumentation more especially, some Trombone passages in the 'Tuba mirum' and 'Benedictus'—even, in one case, to the extent of doubting whether they may not have been purposely introduced, as a mask, 'to screen the fraud of an impostor.' Yet, strange to say, e first of these very passages stands, in the Vienna MS. in Mozart's own handwriting.[5]

Such passages as these, though they may, perhaps, strengthen Süssmayer's claim to have filled in certain parts of the Instrumentation, stand on a very different ground to those which concern the Composition of whole Movements. The 'Lacrymosa' is, quite certainly, one of the most beautiful Movements in the whole Requiem—and Mozart is credited with having only finished the first 8 bars of it! Yet it is impossible to study this movement, carefully, without arriving at Professor Macfarren's conclusion, that 'the whole was the work of one mind, which mind was Mozart's. Süssmayer may have written it out, perhaps; but it must have been from the recollection of what Mozart had played, or sung to him; for, we know that this very Movement occupied the dying Composer's attention, almost to the last moment of his life. In like manner, Mozart may have left no 'Urschriften' of the 'Sanctus,' 'Benedictus,' and 'Agnus Dei'—though the fact that they have never been discovered does not prove that they never existed—and yet he may have played and sung these Movements often enough to have given Süssmayer a very clear idea of what he intended to write. We must either believe that he did this, or that Süssmayer was as great a genius as he; for not one of Mozart's acknowledged Masses will bear comparison with the Requiem, either as a work of Art, or the expression of a devout religious feeling. In this respect, it stands almost alone among Instrumental Masses, which nearly always sacrifice religious feeling to technical display.

(2.) Next in importance to Mozart's immortal work are the two great Requiem Masses of Cherubini. The first of these, in C minor, was written for the Anniversary of the death of King Louis XVI. (Jan. 21, 1793), and first sung, on that occasion, at the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, in 1817; after which it was not again heard until Feb. 14, 1820, when it was repeated, in the same Church, at the Funeral of the Duc de Berri. Berlioz regarded this as Cherubini's greatest work. It is undoubtedly full of beauties. Its general tone is one of extreme mournfulness, pervaded, throughout, by deep religious feeling. Except in the 'Dies iræ' and 'Sanctus' this style is never exchanged for a more excited one; and, even then, the treatment can scarcely be called dramatic. The deep pathos of the little Movement, interposed after the last 'Osanna,' to fulfil the usual office of the 'Benedictus'—which is here incorporated with the 'Sanctus'—exhibits the Composer's power of appealing to the feelings in its most affecting light.

The second Requiem, in D minor, for three Male Voices, is, in many respects, a greater work than the first; though the dramatic element pervades it so freely, that its character as a Religious Service is sometimes entirely lost. It was completed on Sept. 24, 1836, a few days after the Composer had entered his 77th year; and, with the exception of the Sixth Quartet, and the Quintet in E minor, was his last important work. The 'Dies iræ' was first sung at the Concert of the Conservatoire, March 19, 1837, and repeated on the 24th of the same month. On March 25, 1838, the work was sung throughout. In the January of that year, Mendelssohn had already recommended it to the notice of the Committee of the Lower Rhine Festival; and, in 1872 and 1873, it was sung, as a Funeral Service, in the Roman Catholic Chapel, in Farm Street, London. It is doubtful whether Cherubini's genius ever shone to greater advantage than in this gigantic work. Every Movement is replete with interest; and the 'whirlwind of sound' which ushers in the 'Dies iræ' produces an effect, which, once heard, can never be forgotten.

(3.) It remains only to notice a work, which, though a Requiem only in name, takes high rank among the greatest productions of the present day.

The 'German Requiem' of Johannes Brahms is, in reality, a Sacred Cantata, composed to words selected from Holy Scripture, in illustration of the joys of the Blessed, and the glories of the Life to Come. It prefers no claim to be considered as a Religious Service, in any sense of the word; and must, therefore, be criticised, like the great Mass of Sebastian Bach, as a shorter form of Oratorio. So considered, it is worthy of all praise; and exhibits, throughout, a striking originality, very far removed from the eccentricity which sometimes passes under that name, and too frequently consists in the presentation of forms rejected by older Composers by reason of their ugliness. The general style is neither dramatic, nor sensuously descriptive: but, in his desire to shadow forth the glories of a higher state of existence, the Composer has availed himself of all the latest resources of modern Music, including the most complicated Orchestral Effects, and Choral Passages of almost unconquerable difficulty. In the first Movement, an indescribable richness of tone is produced by the skilful management of the Stringed Band, from which the violins are altogether excluded. In the Funeral March, a strange departure from recognised custom is introduced, in the use of Triple Time, which the Composer has compelled to serve his purpose, so completely, that the measured tramp of a vast Procession is as clearly described, and as strongly forced upon the hearer's attention, as it could possibly have been by the ordinary means. The next division of the work introduces two Choral Fugues, founded upon Subjects which each embrace a compass of eleven notes, and differ, in many very important points, both of construction and treatment, from the Motivi employed by other adepts in this particular style of Composition. The Crescendo which separates these two Movements, is, at the same time, one of the most beautiful, and one of the most fearfully difficult passages in the entire work. No. 4 is an exquisitely melodious Slow Movement, in Triple Time; and No. 5, an equally attractive Soprano Solo and Chorus. No. 6 is a very important section of the work, comprising several distinct Movements, and describing, with thrilling power, the awful events connected with the Resurrection of the Dead. Here, too, the fugal treatment is very peculiar; the strongly characteristic Minor Second in the Subject, being most unexpectedly represented by a Major Second in the Answer. The Finale, No. 7, concludes with a lovely reminiscence of the First Movement, and brings the work to an end, with a calm pathos which is the more effective from its marked contrast with the stormy and excited Movements by which it is preceded.

It is impossible to study this important Composition in a truly impartial spirit without arriving at the conclusion that its numerous unusual features are introduced, not for the sake of singularitv, but, with an honest desire to produce certain effects, which undoubtedly are producible, when the Chorus and Orchestra are equal to the interpretation of the author's ideas. The possibility of bringing together a sufficiently capable Orchestra and Chorus has already been fully demonstrated, both in England and in Germany. The 'Deutsches Requiem,' first produced at Bremen, on Good Friday, 1868, was first heard, in this country, at the house of Lady Thompson, London, July 7, 1871, Miss Regan and Stockhausen singing the solos, and Lady Thompson and Mr. Cipriani Potter playing the accompaniment à quatre mains. It was next performed at the Philharmonic Society's Concert, April 2, 1873, and has since been most effectively given by the Bach Choir, and the Cambridge University Musical Society. The excellence of these performances plainly shows that the difficulties of the work are not really insuperable. They may, probably, transcend the power of an average country Choral Society; but we have heard enough to convince us that they may be dealt with successfully by those who really care to overcome them, and we are thus led to hope that after a time the performance of the work may not be looked upon as an unusual occurrence.

[App. p.770 "Mention should be made of the Requiem Masses of Gossec. [See vol. i. p. 611.] Berlioz, whose work is in some respects the most extraordinary setting of the words that has ever been produced, and Verdi, whose setting of the words maybe regarded as marking the transitional point in his style. A work of Schumann's, op. 148, is of small importance; more beautiful compositions of his, with the same title, though having no connection with the ecclesiastical use of the word, are the Requiem for Mignon, and a song included in op. 90. See vol. iii. p. 420 a."][ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ That is to say, its name as a special Mass. The Music of the ordinary Polyphonic Mass always bears the name of the Canto fermo on which it is founded.

- ↑ Paris, Launer et Cie.; London. Schott & Co.

- ↑ See Alfieri, 'Raccolta di Musica Sacra.' Tom. vii.

- ↑ The full details of the remarkable history, which we have here given in the form of a very rapid sketch, will be found in a delightful little brochure, entitled 'The Story of Mozart's Requiem,' by William Pole, F.R.S., Mus. Doc., Oxon. (Novello & Co.)

- ↑ We make this statement on the authority of Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel's latest Score, having had no opportunity of verifying it, by comparison with the original MS., before going to press.