PSALTER, the english Metrical, or paraphrastic rhyming translation of the Psalms and Evangelical Hymns, intended to be sung, dates from the third year of King Edward the Sixth, the year 1549; but if we may believe the accounts usually given of the subject, the practice of singing compositions of this nature in England is far older, having existed among the sympathizers with the new doctrines, long before the Reformation; it may even have had its beginnings among the followers of Wycliffe or Walter Lollard. With regard to this supposition, one thing only is certain: Sternhold's translations—the nucleus of the metrical psalter which has come down to us—were not by any means the first. Sir Thomas Wyat the elder had already translated the seven penitential psalms, and the Earl of Surrey three others; and in 1549, the year in which Sternhold's first small work was published, without tunes, there appeared a metrical translation of the Psalter complete, together with the Evangelical Hymns, and music set in four parts, of which the title is as follows:—

The Psalter of David newely translated into Englysh metre in such sort that it maye the more decently, and wyth more delyte of the mynde, be read and songe of al men. Wherunto is added a [1]note of four partes, with other thynges, as shall appeare in the Epistle to the Readar. Translated and Imprinted by Robert Crowley in the yere of our Lorde MDXLIX the XX daye of September. And are to be sold in Eley rentes in Holbourne. Cum privilegio ad Imprimenaum solum.[2]

In the 'Epistle to the Readar' the music is described thus:—

A note of song of iiii parts, which agreth with the meter of this Psalter in such sort, that it serveth for all the Psalmes thereof, conteyninge so many notes in one part as be syllables in one meter, as appeareth by the dyttie that is printed with the same.

This book is extremely interesting, not only in itself, but because it points to previous works of which as yet nothing is known. In his preface the author says:—'I have made open and playne that which in other translations is obscure and harde,' a remark which must surely apply to something more than the meagre contributions of Surrey and Wyat; and indeed the expression of the title, 'the Psalter of David, newly translated,' seems clearly to imply the existence of at least one other complete version. The metre is the common measure, printed not, as now, in four lines of eight and six alternately, but in two lines of fourteen, making a long rhyming couplet.[3] The verse, compared with other work of the same kind, is of average merit: the author was not, like Surrey or Wyat, a poet, but a scholar turned puritan preacher and printer, who pretended to nothing more than a translation as faithful as possible, considering the necessities of rhyme. But the most interesting thing in the book is the music, which here follows:—

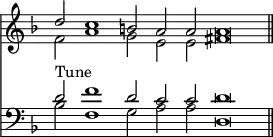

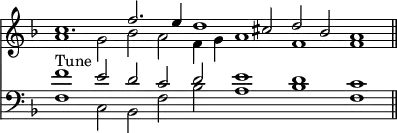

Mode IX.

That man is happy[4] and blessed, that hath not gone a - stray:

Its interest is of several kinds. In the first place it is the earliest music to an English metrical version as yet discovered. It is also a double chant, a musical form hitherto supposed unknown till a hundred years later; and it thus shows by what a simple transition the passage from chanting the prose psalter to singing the metrical one might be accomplished. It would be unwise to argue from this single specimen that it was so accomplished, or that we see here the typical early English metrical psalm-tune; but certainly the discovery of this little composition, so obviously intermediate in character, very much diminishes the probability that anything like the chorale form, which soon afterwards prevailed, was known in England at this time.

We now enter upon the history of what afterwards became the authorized version. In the year 1548 or 1549—it is uncertain which, but possibly early in 1549—appeared a small volume with the following title:—

Certayne Psalmes chosen out of the Psalter of David and drawen into Englishe Metre by Thomas Sternhold, Grome of ye Kynges Maiesties Robes. London, Edvardus Whitchurche.'

This volume, which is without date, contains 19 psalms only, in the double common measure, or four lines of fourteen, by Sternhold alone, without music. Sternhold died in 1549, and on Dec. 14 of that year another edition was published, with a new title:—

All such psalmes of David as Thomas Sternehold late groome of ye Kinges Maiesties Robes didde in his lyfetime draw into English metre. Newly imprinted by Edward Whitchurche.

Besides the original 19, this edition contains 18 by Sternhold; and, printed as a second part, a supplement of 7 by J. Hopkins, without music. This is the volume which in previous accounts of the subject[5] has been usually described as the first edition; and no mention is made of Hopkins's supplement. It has also been usual to describe the contents as 'fifty-one psalms'; the actual number, it will be seen, is 44. Lowndes mentions a second edition of this work in the following year:—'by the widowe of Jhon Harrington, London, 1550.'

In this year also William Hunnis, a gentleman of the Chapel Royal, published a small selection of metrical psalms, in the style of Sternhold, with the following title:—

Certayne Psalms chosen out of the Psalter of David, and drawen furth into English Meter by William Hunnis, London, by the wydow of John Herforde, 1650.

A copy of this work is in the public library of Cambridge. There is no music. In 1553 appeared a third edition of the volume dated 1549, again published by Whitchurche. This edition contains a further supplement of 7 psalms, by Whittingham, thus raising the number to 51. There is still no music. Lowndes mentions another edition of the same year, 'by Thom. Kyngston and Henry Sutton, London.'

To this year also belongs a small volume containing 19 psalms in the common measure, which is seldom mentioned in accounts of the subject, but which is nevertheless of great interest, since it contains music in four parts. The title is as follows:—

Certayne Psalmes select out of the Psalter of David, and drawen into Englyshe Metre, with notes to every Psalme in iiij parts to Synge, by F. S. Imprinted at London by Wyllyam Seres, at the Sygne of the Hedge Hogge, 1553.[6]

In the dedication, to Lord Russell, the author gives his full name, Francys Seagar. The music is so arranged that all the four voices may sing at once from the same book: the parts are separate, each with its own copy of words; the two higher voices upon the left-hand page, the two lower upon the right; all, of course, turning the leaf together. Though the music continues throughout the book, the actual number of compositions is found to be only two, one being repeated twelve times, the other seven. The first is here given:—

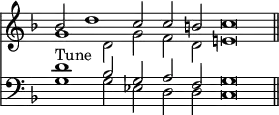

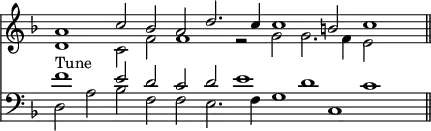

Mode II. Transposed

It will be perceived that we have not yet quite arrived at a tune. The part next above the bass, in descending by one degree upon the final, performs the office of a cantus firmus, but exhibits no other characteristic of a tune that could be sung alone. The composition is in fact a little motet, full of points of imitation, but capable of repetition. It is written in a style which will be easily recognised by those who are acquainted with Dr. Tye's music to his metrical Acts of the Apostles (also published in this year) or with the four-part song 'In going to my naked bed'; a native style, founded upon the secular part-songs of Fayrfax, Cornysshe, Newark, and Banister, which had been growing up during the reign of Henry the Eighth. We see it here, however, in an imperfect shape, and its development into a flowing, consecutive common measure tune is only to be found in Tye's work.[7] It is true that Tye, in the last line of his compositions generally, and occasionally elsewhere, somewhat injured the rhythmical continuity by introducing a point of imitation; but that was so obviously a concession to scholarship, and could with so little difficulty have been altered, that we may certainly ascribe to him the invention of an English form of psalm tune, in four parts, suitable for popular use, and far more beautiful than the tunes in chorale form to which it was compelled to give way. The influence of Geneva was at this time exceedingly powerful in England, and the tendency, slight as it is, to florid descant in Tye's work, must have been to the reformers extremely objectionable; for just as unisonous psalm-singing was to the papist the sign of heresy, so not less to the reformer was florid descant the sign of popery. To this, no doubt, it is owing that no more tunes were written in this style.

The publications of this year probably took place before July, which was the month of the king's death; and nothing further was produced in this country during the reactionary reign of his successor. But in 1556 an edition of Sternhold was published in Geneva, for the use of the Protestants who had taken refuge there, which is extremely important in the history of the subject, since it contains the first instalment of those famous 'Church tunes,' some at least of which have been sung, Sunday after Sunday, in our English churches, from that day to this. The book appeared with a new title:—

One and fiftie Psalmes of David in English metre, whereof 37 were made by Thomas Sterneholde and the rest by others. Conferred with the hebrewe, and in certeyn places corrected as the text, and sens of the Prophete required.[8]

The date is gathered from the second part of the book, which contains the Geneva catechism, form of prayer, and confession, and is printed 'by John Crespin, Geneva, 1556.' No addition, it will be seen, had been made to the number of translations: it only remains, therefore, to speak of the tunes. In one respect this edition differs from all others. Here a new tune is given for every Psalm; in subsequent editions the tunes are repeated, sometimes more than once. They are printed without harmony, in the tenor or alto clef, at the head of the Psalm; the first verse accompanying the notes. The question has often been discussed, what the Church tunes are; what their origin, and who their author. Burney says they are 'mostly German'; but that is impossible, since the translations in the edition of Sternhold which the emigrants took with them to Geneva were all, except one or two, in double common measure; and there are no foreign tunes of this date which will fit that peculiarly English metre. The true answer is probably to be found in Ravenscroft's classified index of the tunes in his Psalter, published in 1621; where, under the heading of 'English tunes imitating the High Dutch, Italian, French and Netherlandish tunes,' will be found almost all the original 'Church tunes' which remained in use in his day. According to this excellent authority, therefore, the 'Church tunes,' as a whole, are English compositions. Furthermore, considering that they appear for the first time in this volume, published at Geneva, three years after the emigration, it becomes exceedingly probable that they are imitations of those which the emigrants found in use at Geneva among the French Protestants; which were chiefly, if not entirely, the tunes composed by Guillaume Franc for the Psalter of Marot and Béza. [See Bourgeois and Franc in App.] Some of the French tunes evidently at once became great favourites with the English Protestants. Already in this volume we find two most interesting attempts to adapt the famous French tune now known as the Old Hundredth to the double common measure. One is set to the 3rd Psalm, the other to the 68th. In both the first line is note for note the same as in the French tune: the difference begins with the difference of metre, in the second line. We find further that as the translation of the Psalter proceeded towards completion, Keith and Whittingham, residents in Geneva, rendered some of the later psalms into special metres, and re-translated others—among them the 100th, in order to provide for the adoption of the most admired French tunes intact: these will be mentioned in detail, so far as they have been as yet identified, later on. The question of authorship is of secondary interest. There were at this time, no doubt, many English musicians capable of composing them, among the organists or singing men in the Cathedrals and Chapels Royal, who are known to have entered almost as warmly as the clergy into the religious discussions of the time, and of whom many took refuge at Geneva along with the clergy. Immediately upon the death of Mary, in 1558, this work found its way to England. The tunes at once became popular, and a strong and general demand was made for liberty to sing them in the churches. In the following year permission was given, in the 49th section of the injunctions for the guidance of the clergy; where, after commanding that the former order of service (Edward's) be preserved, Elizabeth adds:—

And yet nevertheless, for the comforting of such as delight in music, it may be permitted, that in the beginning or in the end of Common Prayer, either at morning or evening, there may be sung an hymn, or such like song, to the praise of Almighty God, in the best melody and music that may be conveniently devised, having respect that the sentence of the hymn may be understood and perceived.

This permission, and the immediate advantage that was taken of it, no doubt did much to increase the popular taste for psalm-singing, and to hasten the completion of the Psalter. For in the course of the next year, 1560, a new edition appeared, in which the number of Psalms is raised to 64, with the following title:[9]—

Psalmes of David in Englishe Metre, by Thomas Sterneholde and others: conferred with the Ebrue, and in certeine places corrected, as the sense of the Prophete required: and the Note joyned withall. Very mete to be used of all sorts of people privately for their godly solace & comfort, laying aparte all ungodly songes & ballades, which tende only to the nourishing of vice, and corrupting of youth. Newly set foarth and allowed, according to the Quenes Maiesties Iniunctions. 1560.

There is no name either of place or of printer, but in all probability it was an English edition. Although no mention is made of them in the title, this work includes metrical versions of three of the Evangelical Hymns, the ten Commandments, the Lord's Prayer, and the Creed. It may have included a few more of the same kind, but the only known copy of the work is imperfect at the end, where these additions are printed as a kind of supplement. The practice of repeating the tunes begins here, for though the number of psalms has been increased, the number of tunes has diminished. There are only 44, of which 23 have been taken on from the previous edition; the rest are new. Among the new tunes will be found five adopted from the French Psalter, in the manner, described above. They are as follows:—The tunes to the French 121st, 124th, and 130th, have been set to the same psalms in the English version; the French 107th has been compressed to suit the English 120th; and the French 124th, though set to the same psalm in the English version, has been expanded by the insertion of a section between the third and fourth of the original; the French psalm having four lines of eleven to the stanza, the English five. The tune for the metrical commandments is the same in both versions.

By the following year 23 more translations were ready; and another edition was brought out, again at Geneva:[10]—

Foure score and seven Psalmes of David in English Mitre, by Thomas Sterneholde and others: conferred with the Hebrewe, and in certeine places corrected, as the sense of the Prophet requireth. Whereunto are added the Songe of Simeon, the then commandments and the Lord's Prayer. 1561.

From the 'Forme of Prayers,' etc., bound up with it, we gather that it was 'printed at Geneva by Zacharie Durand.' The number of tunes had now been largely increased, and raised to a point beyond which we shall find it scarcely advanced for many years afterwards. The exact number is 63; of which 22 had appeared in both previous editions, 14 in the edition of 1560 only, and 2 in the edition of 1556 only. The rest were new. Among the new tunes will again be found several French importations. The tunes for the English 50th and 104th are the French tunes for the same psalms. The 100th is the French 134th, the 113th the French 36th, the 122nd the French 3rd, the 125th the French 21st, the 126th the French 90th. The 145th and 148th are also called 'French' by Ravenscroft.[11] Thus far there is no sign of any other direct influence. The imported tunes, so far as can be discovered, are all French; and the rest are English imitations in the same style.

Before we enter upon the year 1562, which saw the completion of Sternhold's version, it is necessary that some account should be given of another Psalter, evidently intended for the public, which had been in preparation for some little time, and was actually printed, probably in 1560, but which was never issued;—the Psalter of Archbishop Parker. The title is as follows:—

The whole Psalter translated into English metre, which contayneth an hundreth and fifty psalmes, Imprinted at London by John Daye, dwelling over Aldersgate beneath S. Martyn's. Cum gratia et privilegio Regiæ maiestatis, per decennium.

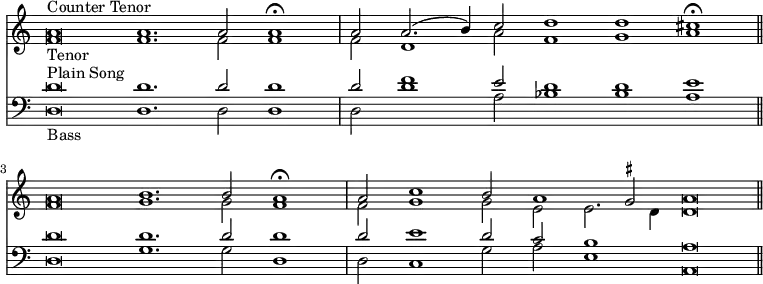

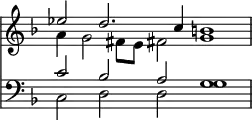

The privilege sufficiently proves the intention to publish. It seems at first sight curious, that while it has been necessary to speak of the copies of published works hitherto referred to as unique, it should be possible to say of this, which was never given to the public, that at least four or five examples are in existence. The reason, however, is no doubt to be found in the fact that the few copies struck off as specimens were distributed to select persons, and so, finding their way at once into careful hands, were the better preserved. The existing copies, so far as they have been compared, correspond exactly; and show that the work was complete, lacking nothing except the date, for which a blank space was left at the foot of the title page. The verse of this translation, which is in various metres, is in every way far superior to that of Sternhold's; but though the author has evidently aimed at the simplicity and directness of his original, he is frequently obscure. The suppression of the work, however, was probably not due to any considerations of this kind, but either to the enormous popularity of Sternhold's version, which was every day becoming more manifest, or, as it has been sometimes supposed, to a change in the author's opinion as to the desirability of psalm-singing. In any case, it is much to be regretted, since it involved the suppression of nine tunes, specially composed by Tallis, in a style peculiar to himself, which, if the work had been published, would at all events have once more established the standard of an English tune in four parts, broad, simple, and effective, and suitable for congregational use; and, from the technical point of view, finer than anything of the kind that has been done since. Whether it would have prevailed or not, it is impossible to say. We have seen how, in the case of Tye, the influence of Geneva triumphed over the beauty of his music; and that influence had become stronger in the interval. On the other hand, the tendency to florid descant, so hateful to the reformers, was absent from the work of Tallis. The compositions in this book are printed, in the manner then customary, in separate parts, all four being visible at once. They are in nearly plain counterpoint; the final close is sometimes slightly elaborated, but generally the effect—which is one of great richness, solemn or sweet according to the nature of the particular scale—is obtained by very simple means. Eight of the tunes are in the first eight modes, and are intended for the psalms; the ninth, in Mode XIII, is supplementary, and is set to a translation of 'Veni Creator.' Two of them have been revived, and are now well known. One appears in our hymnals as 'Tallis,' and is the supplementary tune in Mode XIII.; the other, generally set to Bishop Ken's evening hymn, and known as 'Canon,' is the tune in Mode VIII. With regard to the latter, it should be mentioned that in the original it is twice as long as in the modern form, every section being repeated before proceeding to the next. With this exception the melodies appear as they were written; but, as regards the three other parts, only such fragments have been retained as have happened to suit the taste or convenience of compilers. In the original, too, the tenor leads in the canon; this is reversed in the modern arrangement. The example here given, which is the tune in Mode I, is in a more severe and solemn strain than the two just mentioned. The treatment of the B—natural in the first half of the tune, and flat in the latter half is in the finest manner of Dorian harmony.[12]

Mode I.

The instruction with regard to the tunes is as follows:—

The tenor of these partes be for the people when they will syng alone, the other parts, put for greater queers, or such as will syng or play them privatlye.

The method of fitting the psalms to appropriate tunes is very simple. At the head of each psalm stands an accent grave, acute, or circumflex indicating its nature as sad, joyful, or indifferent, according to the author's notion: the tunes bear corresponding accents. The work is divided into three parts, each containing fifty psalms; and since it is only in the third part that these accents appear, (together with a rather ingenious system of red and black brackets, showing the rhyming structure of the verse,) we may perhaps conclude that the work was not all printed at once, and that it was only towards the end—possibly after the promulgation of Elizabeth's injunctions—that it was thought desirable to have tunes composed.

It seems certain that the first complete edition of this version, containing the whole Psalms, the Evangelical Hymns, and the Spiritual Songs, was published in 1562, and that another followed in 1563; but the earliest now in existence is the one of 1564, of which the title is as follows:

'The whole booke of Psalms collected into Englysh Meter, by Thomas Sternhold, J. Hopkins, and others, conferred with the Hebrew, with apt notes to sing them withal, faithfully perused and allowed according to thorder appoynted in the Queenes maiestyes Iniunctions. Very meet,' etc., as in the edition of 1560. 'Imprinted at London by John Daye, dwelling over Aldersgate. Cum gratia et privilegio regiæ Maiestatis per septenniuin. 1564.'

The number of tunes in this edition is 65; of which 14 had appeared in all the previous editions, 7 in the editions of 1560 and 1561 only, and 7 in the edition of 1561 only, and 4 in the edition of 1560 only. The rest were new. Nothing more had been taken from the French Psalter; but two tunes which Ravenscroft calls 'High Dutch' were adopted. One of them, set to Wisdome's prayer 'Preserve us, Lord, by thy dear word,' was identified by Burney with the so-called Luther Chorale set to similar words. It will have been observed that a considerable re-arrangement of the tunes had hitherto taken place in every new edition; the tunes which were taken on from previous editions generally remained attached to the same psalms as before, but the number of new tunes, as well as of those omitted, was always large. Now, however, the compilers rested content; and henceforward, notwithstanding that a new edition was published almost yearly, the changes were so gradual that it will only be necessary to take note of them at intervals. The tunes are printed without bars, and in notes of unequal length. Semibreves and minims are both used, but in what seems at first sight so unsystematic a way—since they do not correspond with the accents of the verse—that few of the tunes, as they stand, could be divided into equal sections; and some could not be made to submit to any time-signature whatever. In this respect they resemble the older ecclesiastical melodies. The idea of imitation, however, was probably far from the composer's mind, and the object of his irregularity was no doubt variety of effect; the destruction of the monotonous swing of the alternate eight and six with accents constantly recurring in similar positions. To the eye the tunes appear somewhat confused; but upon trial it will be found that the long and short notes have been adjusted with great care, and, taking a whole tune together, with a fine sense of rhythmical balance. The modes in which these compositions are written are such as we should expect to meet with in works of a popular, as opposed to an ecclesiastical, character. The great majority of the tunes will be found to be in the modes which have since become our major and minor scales. The exact numbers are as follows:—28 are in Modes XIII. and XIV., 23 in Modes IX. and X., 12 in Modes I. and II., one in Mode VII., and one in Mode VIII. All these modes, except the last two, are used both in their original and transposed positions.

A knowledge of music was at this time so general, that the number of persons able to sing or play these tunes at sight was probably very considerable. Nevertheless, in the edition of 1564, and again in 1577, there was published 'An Introduction to learn to sing,' consisting of the scale and a few elementary rules, for the benefit of the ignorant. The edition of 1607 contained a more elaborate system of rules, and had the sol-fa joined to every note of the tunes throughout the book; but this was not repeated, nor was any further attempt made, in this work, to teach music.

For competent musicians, a four-part setting of the church tunes was also provided by the same publisher:—

The whole psalmes in foure partes, which may be song to al musicall instrumentes, set forth for the encrease of vertue, and abolishyng of other vayne and triflyng ballades. Imprinted at London by John Day, dwelling over Aldersgate, beneath Saynt Martyns. Cum gratia et privilegio Regiæ Maiestatis, per septennium. 1563.[13]

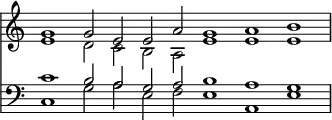

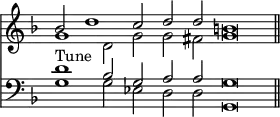

Notwithstanding this title, only the first verse of each Psalm is given; enough to accompany the notes once, and no more: it is therefore only a companion to Sternhold; not, like almost all subsequent works of the kind, a substitute. But in other respects it was designed on a much larger scale than anything that appeared afterwards. It is in four volumes, one for each voice. Every composition, long or short, occupies a page; and at the head of each stands one of the fine pictorial initial letters which appear in all Day's best books about this time. But it is as regards the quantity of the music that it goes farthest beyond all other collections of the same kind. The composers of subsequent Psalters thought it quite sufficient, as a rule, to furnish each of the 65 church tunes with a single setting; but here, not only has each been set, but frequently two and sometimes three and four composers have contributed settings of the same tune; and as if this were not enough, they have increased the work by as many as 30 tunes, not to be found in Sternhold, and for the most part probably original. The total result of their labours is a collection of 141 compositions, of which 4 are by N. Southerton, 11 by R. Brimle, 17 by J. Hake, 27 by T. Causton, and 81 by W. Parsons. It is worthy of remark that while all the contemporary musicians of the first rank had already been employed upon contributions to the liturgical service, not only by way of MSS., but also in the printed work, 'Certayne notes,' etc. issued by Day in 1560,—the composers to whom the publisher had recourse for this undertaking are all, except one,[14] otherwise unknown. Nor is their music, though generally respectable and sometimes excellent, of a kind that requires any detailed description: it will be sufficient to mention a few of its most noticeable characteristics, interesting chiefly from the insight they afford into the practice of the average proficient at this period. The character of these compositions in most cases is much the same as that of the simple settings of the French Psalter by Goudimel and Claude le Jeune; the parts usually moving together, and the tenor taking the tune. The method of Causton, however, differs in some respects from that of his associates: he is evidently a follower of Tye; showing the same tendency towards florid counterpoint, and often indeed using the same figures. He is, as might be expected, very much Tye's inferior in invention, and moreover still retains some of the objectionable collisions, inherited by the school of this period from the earlier descant, which Tye had refused to accept.[15] Brimle offends in the same way, but to a far greater extent: indeed, unless he has been cruelly used by the printer, he is sometimes unintelligible. In one of his compositions, for instance, having to accommodate his accompanying voices to a difficult close in the melody, he has written as follows:—[16]

The difficulty arising from the progression of the melody in this passage was one that often presented itself during the process of setting the earliest versions of the church tunes. It arose whenever the melody, in closing, passed by the interval of a whole tone from the seventh of the scale to the final. When this happened, the final cadence of the mode was of course impossible, and some sort of expedient became necessary. Since, however, no substitute for the proper close could be really satisfactory because, no matter how cleverly it might be treated, the result must necessarily be ambiguous—in all such cases the melody was sooner or later altered. As these expedients do not occur in subsequent Psalters, two other specimens are here given of a more rational kind than the one quoted above.

Both Parsons[18] and Hake appear to have been excellent musicians. The style of the former is somewhat severe, sometimes even harsh, but always strong and solid. In the latter we find more sweetness; and it is characteristic of him that, more frequently than the others, he makes use of the soft harmony of the imperfect triad in its first inversion. It should be mentioned that of the 17 tunes set by him in this collection, 7 were church tunes, and 10 had previously appeared in Crespin's edition of Sternhold, and had afterwards been dropped. His additions, therefore, were none of them original. One other point remains to be noticed. Modulation, in these settings, is extremely rare; and often, when it would seem—to modern ears at least—to be irresistibly suggested by the progression of the melody, the apparent ingenuity with which it has been avoided is very curious. In the tune given to the 22nd Psalm, for instance, which is in Mode XIII (final, C), the second half begins with a phrase which obviously suggests a modulation to the dominant:—

but which has been treated by Parsons follows:—[19]

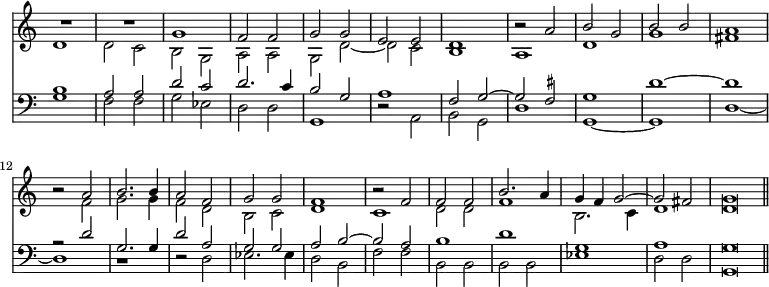

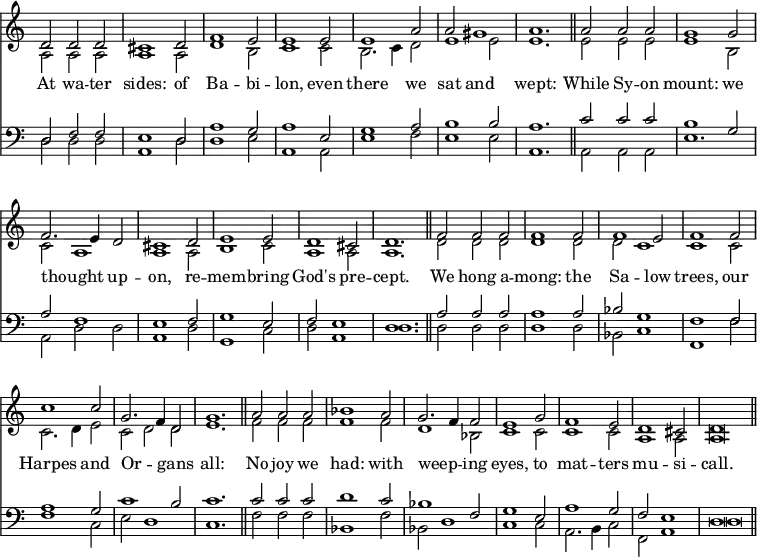

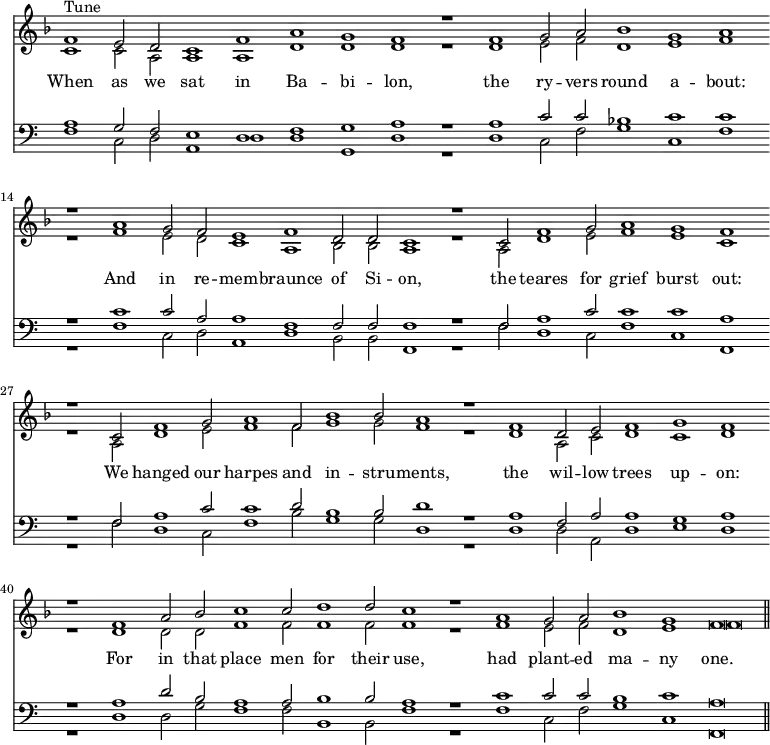

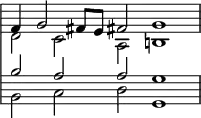

The importance of this Psalter, at once the first and the most liberal of its kind, entitles it to a complete example of its workmanship. The tune chosen is that to the 137th Psalm, an excellent specimen of the English imitations of the French melodies, and interesting also as being one of the two tunes which, appearing among the first printed—in Crespin's edition of Sternhold,—are in use at this day. It was evidently a favourite with Parsons, who has set it three times; twice placing it in the tenor, and once in the upper voice. The latter setting is the one here given:—[20]

Mode XIV. Transposed.

Psalm cxxxvii.

W Parsons.

At the end of the book are to be found a few miscellaneous compositions, some in metre and some in prose, evidently not specially intended for this work, but adopted into it. Some of these are by the musicians employed upon the Psalter; but there are also two by Tallis, and one each by Shephard and Edwards.

The ample supply of four-part settings contained in Day's great collection seems to have so far satisfied the public craving, that during the next sixteen years no other publication of the same kind was attempted. Nor had the work which appeared at the end of that period been composed with any kind of desire to rival or succeed the existing one; it had, in fact, never been intended for the public, and was brought out without the permission, or even the knowledge of its author. Its title was as follows:—

The Psalmes of David in English meter with notes of foure partes set unto them by Guilielmo Damon, for John Bull, to the use of the godly Christians for recreatyng themselves, instede of fond and unseemly Ballades. Anno 1579 at London Printed by John Daye. Cum privilegio.

The circumstances of this publication, as they were afterwards related, were shortly these. It was Damon's custom, on the occasion of each of his visits to his friend, Mr. John Bull, to compose, and leave behind him, a four-part setting of some one of the church tunes; and these, when the collection was complete, Bull gave to the printer, without asking the author's consent. The preface, by one Edward Hake, is kind of apology, partly for the conduct of the above-mentioned Mr. John Bull, 'citizen and goldsmith of London,' and partly for the settings themselves, of which he says that they were 'by peece meale gotten and gathered together from the fertile soyle of his honest frend Guilielmo Damon one of her Maiesties Musitions,' who 'never meant them to the use of any learned and cunnyng Musition, but altogether respected the pleasuryng of his private frend.' The settings—one only to each tune—are very much of the kind that might be expected from the circumstances. They are in plain counterpoint, with the tune in the tenor; evidently the work of a competent musician, but without special merit. The book contains 14 tunes not to be found in Day, and among these are the first four of those single common measure tunes which later quite took the place in popular favour of all but a few of the older double kind. They had not as yet been named, but they were afterwards known as Cambridge, Oxford, Canterbury, and Southwell. Two of the church tunes have been dropped; and it should also be remarked that in many tunes the value of the notes has been altered, the alteration being, in all cases, the substitution of a minim for a semibreve.

Warton mentions a small publication, 'VII Steppes to heauen, alias the vij [penitential] Psalmes reduced into meter by Will Hunnys,'[21] which he says was brought out by Henry Denham in 1581; and 'Seuen sobs of a sorrowfull soule for sinne,' published in 1585, was, according to the same authority, a second edition of the same work with a new title. The later edition contains seven tunes in double common measure, in the style of the church tunes, exceedingly well written, and quite up to the average merit of their models. Burney and Lowndes both mention a collection of settings with the following title:—

Musicke of six and five parts made upon the common tunes used in singing of the Psalmes by John Cosyn, London by John Wolfe 1585.[21]

Another work, called by Canon Havergal the 'Psalter of Henrie Denham,'[21] is said to have been published in 1588.

Damon seems to have been considerably annoyed to find that compositions which he thought good enough for Mr. Bull, had been by Mr. Bull thought good enough for the public; and, as a protest against the injustice done to his reputation, began, and lived long enough to finish, two other separate and complete settings of the church tunes, in motet fashion; the tunes in the first being in the tenor, and in the second in the upper voice. They were brought out after his death by a friend, one William Swayne, from whose preface we learn the particulars of the publication of 1579. The titles are as follows:—

1. The former booke of the Musicke of M. William Damon late one of her maiesties Musitions: conteining all the tunes of David's Psalmes, as they are ordinarily soung in the Church: most excellently by him composed into 4 parts. In which sett the Tenor singeth the Church tune. Published for the recreation of such as delight in Musicke: by W. Swayne Gent. Printed by T. Este, the assigné of W. Byrd. 1591.2. The second Booke of the Musicke of M. William Damon, conteining all the tunes of David's Psalmes, differing from the former in respect that the highest part singeth the Church tune, etc.

In both these works the compositions are in the same rather ornate style; points of imitation are frequently taken upon the plain song, the parts from time to time resting, in the usual manner of the motet. Their whole aim is, in fact, more ambitious than that of any other setting of the church tunes. Twelve of the original tunes have been dropped; and one in single common measure, added, the tune afterwards known as Windsor or Eton. [See Windsor Tune.]

Este, the publisher of these two works, must have been at the same time engaged upon the preparation of his own famous Psalter, for in the course of the next year it was brought out, with the following title:—

The whole booke of psalmes: with their wonted Tunes, as they are song in Churches, composed into foure parts: All which are so placed that foure may sing ech one a seueral part in this booke. Wherein the Church tunes are carefully corrected, and thereunto added other short tunes usually song in London, and other places of this Realme. With a table in the end of the booke of such tunes as are newly added, with the number of ech Psalme placed to the said Tune. Compiled by sondry avthors who haue so laboured herein, that the vnskilfull with small practice may attaine to sing that part, which is fittest for their voice. Imprinted at London by Thomas Est, the assigné of William Byrd: dwelling in Aldersgate streete at the signe of the Black Horse and are there to be sold. 1592.[22]

It seems to have been part of Este's plan to ignore his predecessor. He has dropped nine of the tunes which were new in Damon's Psalters, and the five which he has taken on appear in his 'Note of tunes newly added in this booke.' Four of these five were those afterwards known as Cambridge, Oxford, Canterbury, and Windsor, and the first three must already have become great favourites with the public, since Cambridge has been repeated 29 times, Oxford 27 times, and Canterbury 33 times. The repetition, therefore, is now on a new principle: the older custom was to repeat almost every tune once or twice, but in this Psalter the repetition is confined almost entirely to these three tunes. Five really new tunes, all in single common measure, have been added. To three of these, names, for the first time, are given; they are 'Glassenburie,' 'Kentish' (afterwards Rochester), and 'Chesshire.' The other two, though not named as yet, afterwards became London and Winchester.

For the four-part settings Este engaged ten composers, 'being such,' he says in his preface, 'as I know to be expert in the Arte and sufficient to answere such curious carping Musitions, whose skill hath not been employed to the furthering of this work.' This is no empty boast: 17 of the settings are by John Farmer; 12 by George Kirbye; 10 by Richard Allison; 9 by Giles Farnaby; 7 by Edward Blancks; 5 by John Douland; 5 by William Cobbold; 4 by Edmund Hooper; 2 by Edward Johnson, and 1 by Michael Cavendish. It will be observed that though most of these composers are eminent as madrigalists, none of them, except Hooper, and perhaps Johnson, are known as experts in the ecclesiastical style: a certain interest therefore belongs to their settings of plainsong; a kind of composition which they have nowhere attempted except in this work.[23] The method of treatment is very varied: in some cases the counterpoint is perfectly plain; in others plain is mixed with florid; while in others again the florid prevails throughout. In the plain settings no great advance upon the best of those in Day's Psalter will be observed. Indeed, in one respect,—the melodious progression of the voices,—advance was scarcely possible; since equality of interest in the parts had been, from the very beginning, the fundamental principle of composition. What advance there is will be found to be in the direction of harmony. The ear is gratified more often than before by a harmonic progression appropriate to the progression of the tune. Modulation in the closes, therefore, becomes more frequent; and in some cases, for special reasons, a partial modulation is even introduced in the middle of a section. In all styles, a close containing the prepared fourth, either struck or suspended, and accompanied by the fifth, is the most usual termination; but the penultimate harmony is also sometimes preceded by the sixth and fifth together upon the fourth of the scale. The plain style has been more often, and more successfully, treated by Blancks than by any of the others. He contrives always to unite solid and reasonable harmony with freedom of movement and melody in the parts; indeed, the melody of his upper voice is often so good that it might be sung as a tune by itself. But by far the greater number of the settings in this work are in the mixed style, in which the figuration introduced consists chiefly of suspended concords (discords being still reserved for the closes), passing notes, and short points of imitation between two of the parts at the beginning of the section. It is difficult to say who is most excellent in this manner. Farmer's skill in contriving the short points of imitation is remarkable, but one must also admire the richness of Hooper's harmony, Allison's smoothness, and the ingenuity and resource shown by Cobbold and Kirbye. The two last, also, are undoubtedly the most successful in dealing with the more florid style, which, in fact, and perhaps for this reason, they have attempted more often than any of their associates. They have produced several compositions of great beauty, in which most of the devices of counterpoint have been introduced, though without ostentation or apparent effort.

Farnaby and Johnson were perhaps not included in the original scheme of the work, since they do not appear till late, Johnson's first setting being Ps. ciii. and Farnaby's Ps. cxix. They need special, but not favourable, mention; because, although their compositions are thoroughly able, and often beautiful—Johnson's especially so—it is they who make it impossible to point to Este's Psalter as a model throughout of pure writing. The art of composing for concerted voices in the strict diatonic style had reached, about the year 1580, probably the highest point of excellence it was capable of. Any change must have been for the worse, and it is in Johnson and Farnaby that we here see the change beginning.[24]

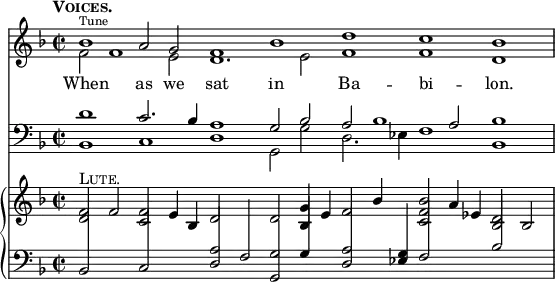

There is, however, one Psalter which can be said to show the pure Elizabethan counterpoint in perfection throughout. It is entirely the work of one man, Richard Allison, already mentioned as one of Este's contributors, who published it in 1599, with the following title:

The Psalmes of David in Meter, the plaine song beeing the common tunne to be sung and plaide upon the Lute, Orpharyon, Citterne or Base Violl, severally or altogether, the singing part to be either Tenor or Treble to the instrument, according to the nature of the voyce, or for fowre voyces. With tenne short Tunnes in the end, to which for the most part all the Psalmes may be usually sung, for the use of such as are of mean skill, and whose leysure least serveth to practize. By Richard Allison Gent. Practitioner in the Art of Musicke, and are to be solde at his house in the Dukes place neere Alde-Gate London, printed by William Barley, the asigné of Thomas Morley. 1599.

The style of treatment employed by Allison in this work—in which he has given the tune to the upper voice throughout—is almost the same as the mixed style adopted by him in Este's Psalter. Here, after an interval of seven years, we find a slightly stronger tendency towards the more florid manner, but his devices and ornaments are still always in perfectly pure taste.[25] The lute part was evidently only intended for use when the tune was sung by a single voice, since it is constructed in the manner then proper to lute accompaniments to songs, in which the notes taken by the voice were omitted. Sir John Hawkins, in his account of the book, makes a curious mistake on this point. He says, 'It is observable that the author has made the plainsong or Church tune the cantus part, which part being intended as well for the lute or cittern, as the voice, is given also in those characters called the tablature which are peculiar to those instruments.' That the exact opposite is the case,[26] will be seen from the translation of a fragment of the lute part, here given:—

The next Psalter to be mentioned is one which seems to have hitherto escaped notice. It was issued without date; but since collation with Este's third edition proves it to be later than 1604, and since we know that its printer, W. Barley, brought out nothing after the year 1614, it must have been published in the interval between those two dates. Its title is as follows:—

The whole Booke of Psalmes. With their woonted Tunes, as they are sung in Churches, composed into foure parts. Compiled by sundrie Authors, who have so laboured herein, that the unskilful with small practise may attaine to sing that part, which is fittest for their voice. Printed at London in little S. Hellens by W. Barley, the assigne of T. Morley, and are to be sold at his shop in Gratious street. Cum privilegio.

From this title, and from the fact that Morley was the successor to Byrd, whose assignee Este was, it would be natural to infer that the work was a further edition of Este's Psalter: and from its contents, it would seem to put forward some pretence to be so. But it differs in several important respects from the original. Este's Psalter was a beautiful book, in octavo size, printed in small but perfectly clear type; the voice parts separate, but all visible at once, and all turning the leaf together. Barley's Psalter is reduced to duodecimo size, becoming in consequence inconveniently thick; it is badly printed; and the parts, though separate, do not always turn the leaf together. Worse than this, in almost all the settings, the two upper voice parts are omitted, and the remaining parts—the tune and the bass—being separate are rendered useless even to the organist, the only person who could have turned two parts to any sort of account. The work, therefore, is so unsatisfactory as to be scarcely worthy of notice, did it not contain ten new and admirable settings, of which four are by Morley himself, five by John Bennet, and one by Farnaby. These not only save the book, but render it valuable; for in Ravenscroft's Psalter, published a few years later, only five of them—two by Morley, and three by Bennet—survive. This work therefore contains six compositions by eminent musicians which are not to be found elsewhere. They are of course printed entire, as are also the settings of the two established and often repeated favourites above referred to, Oxford and Cambridge tunes, and a few others, which, however, though they have escaped mutilation, have not escaped alteration, considerable changes being sometimes made in the parts. In some of the mutilated settings, also, the bass part has been altered, and in some a new bass has been substituted for the old one, while the editor has allowed the name of the original composer to stand above the tune. Examples of extreme carelessness in editing might also be given, were it worth while to do so. On the whole, the book is somewhat of a puzzle. There would be nothing surprising in its peculiarities had it been some unauthorized or piratical edition of Este; but when we remember that the printer was working under the royal patent granted to Morley, and that Morley himself, and another musician almost as distinguished, contributed to it some of the best settings of church tunes ever composed, it becomes difficult to account for its badness.[27] Besides the new settings of old tunes, it also contains one new tune set by Blancks, afterwards called by Ravenscroft a Dutch tune.

Ravenscroft's Psalter, which comes next in order, was published in 1621, with the following title:—

The whole Booke of Psalmes with the Hymnes Evangelicall and Songs Spirituall. Composed into four parts by sundry authors, to such severall tunes, as have been, and are generally sung in England, Scotland, Wales, Germany, Italy, France, and the Netherlands: never as yet before in one volume published… Newly corrected and enlarged by Thomas Ravenscroft Bachelar of Musicke. Printed at London, for the Company of Stationers.[28]

This Psalter contains a larger number of compositions than any other except that of Day; but the number in excess of the Church tunes is not made up, as in Day, by alternative settings, but by the addition of 40 new tunes, almost all of which are single common measure tunes of the later kind, with names. They appear in the index under the heading—'such tunes of the Psalmes usually sung in Cathedrall Churches, Collegiat Chapels, &c.,' and are divided broadly into three classes, one of which contains those named after the English Cathedrals and Universities, while the other two are called respectively Scotch and Welsh, and the tunes named accordingly. The whole subject of these names, and how they are to be understood, has been gone into at some length by Canon Havergal in the preface to his quasi-reprint of this Psalter; and his conclusion is probably the right one, namely, that the tunes were in most cases designated according to the localities in which they were found in use, but that this does not necessarily imply a local origin. We have already referred to Ravenscroft's description of the old double common measure tunes, and need add nothing here with respect to them. Under the heading 'forraigne tunes usually sung in Great Brittaine' will be found, for the French, only the few tunes taken from the Geneva Psalter, enumerated above; with regard to other sources, the magnificent promise of the title-page is reduced to three German tunes, two Dutch, and one Italian.

Of the 100 settings in this work, 38 had appeared in previous ones. All the musicians engaged upon Este's Psalter are represented here; 31 of their compositions have been taken on, and Douland and Hooper have each contributed a new one; Douland's is the setting of the 100th Psalm, already given in this work. [See Hymn, vol. i. p. 762b.] Also, one of Parsons' settings has been taken from Day's Psalter, though not without alteration. The four settings by Morley and Bennet, from Barley's Psalter, have already been mentioned, and in addition there is a new one by Morley, a setting of the 1st Psalm. Tallis's tune in Mode VIII is also given here from Parker's Psalter (to a morning hymn), in the shortened form, but with the tenor still leading the canon.

Eight new composers appear, whose names and contributions are as follows: R. Palmer, 1; J. Milton, 2; W. Harrison, 1; J. Tomkins, 1; T. Tomkins, 2; W. Cranfield or Cranford, 2; J. Ward, 1; S. Stubbs, 2; Ravenscroft himself, 48. In the work of all these composers is to be seen the same impurity of taste which was visible in the settings made for Este by Farnaby and Johnson. The two cadences given above in a note, as examples of a kind of aberration, are here found to have become part of the common stock of music; and an inferior treatment of conjunct passages in short notes, in which the alternate crotchet is dotted, finds, among other disimprovements, great favour with the editor. Ravenscroft and Milton appear to be by far the best of the new contributors. The variety shown by the former in his methods of treatment is remarkable: he seems to have formed himself upon Este's Psalter, to have attempted all its styles in turn, and to have measured himself with almost every composer. Notwithstanding this, it is evident that he had no firm grasp of the older style, and that he was advancing as rapidly as any musician of his day towards the modern tonality and the modern priority of harmonic considerations in part writing. Milton's two settings are fine, notwithstanding the occasional use of the degraded cadence, and on the whole worthy of the older school, to which indeed he properly belonged. The rest, if we except Ward, may be briefly dismissed. They were inferior men, working with an inferior method.

Two years later appeared the work of George Wither:—

The Hymnes and Songs of the Church. Divided into two Parts. The first Part comprehends the Canonicall Hymnes, and such parcels of Holy Scripture as may properly be sung: with some other ancient Songs and Creeds. The second Part consists of Spirituall Songs, appropriated to the severall Times and Occasions, observable in the Church of England. Translated and composed by G. W. London, printed by the assignes of George Wither, 1623. Cum privilegio Regis Regali.

This work was submitted during its progress to James the First, and so far found favour that the author obtained a privilege of fifty-one years, and a recommendation in the patent that the book should be 'inserted in convenient manner and due place in every English Psalm book in metre.' The king's benevolence, however, was of no effect; the Company of Stationers, considering their own privilege invaded, declared against the author, and by every means in their power, short of a flat refusal, avoided the sale of the book. Here again, as in the case of Parker's Psalter, the virtual suppression of the work occasioned the loss of a set of noble tunes by a great master. Sixteen compositions by Orlando Gibbons had been made for it, and were printed with it. They are in two-part counterpoint, nearly plain, for treble and bass; the treble being the tune, and the bass, though not figured, probably intended for the organ. In style they resemble rather the tunes of Tallis than the imitations of the Geneva tunes to which English congregations had been accustomed, it being possible to accent them in the same way as the words they were to accompany; syncopation, however, sometimes occurs, but rarely, and more rarely still in the bass. The harmony often reveals very clearly the transitional condition of music at this period. For instance, in Modes XIII and XIV a sectional termination in the melody on the second of the scale was always, in the older harmony, treated as a full close, having the same note in the bass; here we find it treated in the modern way, as a half close, with the fifth of the scale in the bass. Two of these tunes, altered, appear in modern hymnals.[29]

In 1632 an attempt was made to introduce the Geneva tunes complete into this country. Translations were made to suit them, and the work was brought out by Thomas Harper. It does not seem, however, to have reached a second edition. The enthusiasm of earlier days had no doubt enabled the reformers to master the exotic metres of the few imported tunes; but from the beginning the tendency had been to simplify, and, so to speak, to anglicize them; and since the Geneva tunes had remained unchanged, Harper's work must have presented difficulties which would appear quite insuperable to ordinary congregations.

We have now arrived at the period when the dislike which was beginning to be felt by educated persons for the abject version of Sternhold was to find practical expression. Wither had intended his admirable translation of the Ecclesiastical Hymns and Spiritual Songs to supersede the older one, and in 1636 George Sandys, a son of the Archbishop, published the complete psalter, with the following title:—

A paraphrase upon the Psalms of David, by G. S. Set to new tunes for private devotion; and a thorough bass, for voice or instrument. By Henry Lawes, gentleman of His Majesty's Chapel Royal.[29]

The tunes, 24 in number, are of great interest. Lawes was an ardent disciple of the new Italian school; and these two-part compositions, though following in their outline the accustomed psalm-tune form, are in their details as directly opposed to the older practice as anything ever written by Peri or Caccini. The two parts proceed sometimes for five or six notes together in thirds or tenths; the bass is frequently raised a semitone, and the imperfect fifth is constantly taken, both as a harmony and as an interval of melody. The extreme poverty of Lawes's music, as compared with what was afterwards produced by composers following the same principles, has prevented him from receiving the praise which was certainly his due. He was the first English composer who perceived the melodies to which the new system of tonality was to give rise; and in this volume will be found the germs of some of the most beautiful and affecting tunes of the 17th and 18th centuries: the first section of the famous St. Anne's tune, for instance, is note for note the same as the first section of his tune to the 9th psalm. Several of these tunes, complete, are to be found in our modern hymnals.

The translation of Sandys was intended, as the title shows, to supersede Sternhold's in private use; but several others, intended to be sung in the churches, soon followed. Besides the translation of Sir. W. Alexander (published in Charles the First's reign), of which King James had been content to pass for the author, there appeared, during the Commonwealth, the versions of Bishop King, Barton, and Rous. None, however, require more than a bare mention, since they were all adapted to the Church tunes to be found in the current editions of Sternhold, and have therefore only a literary interest. Nothing requiring notice here was produced until after the Restoration, when, in 1671, under circumstances very different from any which had decided the form of previous four-part psalters, John Playford brought out the first of his well-known publications:—

Psalms and Hymns in solemn musick of foure parts on the Common Tunes to the Psalms in Metre: used in Parish Churches. Also six Hymns for one voyce to the Organ. By Iohn Playford. London, printed by W. Godbid for J. Playford at his shop in the Inner Temple. 1671.

This book contains only 47 tunes, of which 35 were taken from Sternhold (including 14 of the single common measure tunes with names, which had now become Church tunes), and 12 were new. But Playford, in printing even this comparatively small selection, was offering to the public a great many more than they had been of late accustomed to make use of. The tunes in Sternhold were still accessible to all; but not only had the general interest in music been steadily declining during the reigns of James and Charles, but the authorized version itself, from long use in the churches, had now become associated in the minds of the Puritans with the system of Episcopacy, and was consequently unfavourably regarded, the result being that the number of tunes to which the psalms were now commonly sung, when they were sung at all, had dwindled down to some half dozen. These tunes may be found in the appendix to Bishop King's translation, printed in 1651. According to the title-page, his psalms were 'to be sung after the old tunes used in ye churches,' but the tunes actually printed are only the old 100th, 51st, 81st, 119th, Commandments, Windsor, and one other not a Church tune. 'There be other tunes,' adds the author, 'but being not very usuall are not here set down.' The miserable state of music in general at the Restoration is well known, but, as regards psalmody in particular, a passage in Playford's preface so well describes the situation and some of its causes, that it cannot be omitted here:—

For many years, this part of divine service was skilfully and devoutly performed, with delight and comfort, by many honest and religious people: and is still continued in our churches, but not with that reverence and estimation as formerly: some not affecting the translation, others not liking the music: both, I must confess need reforming. Those many tunes formerly used to these Psalms, for excellency of form, solemn air, and suitableness to the matter of the Psalms, were not inferior to any tunes used in foreign churches; but at this day the best, and almost all the choice tunes are lost, and out of use in our churches; nor must we expect it otherwise, when in and about this great city, in above one hundred parishes there is but few parish clerks to be found that have either ear or understanding to set one of these tunes musically as it ought to be: it having been a custom during the late wars, and since, to choose men into such places, more for their poverty than skill or ability; whereby this part of God's service hath been so ridiculously performed in most places, that it is now brought into scorn and derision by many people.

The settings are all by Playford himself. They are in plain counterpoint, and the voices indicated are Alto, Countertenor, Tenor, and Bass, an arrangement rendered necessary by the entire absence, at the Restoration, of trained trebles.

This publication had no great success, a result ascribed by the author to the folio size of the book, which he admits matle it inconvenient to 'carry to church.' His second psalter, therefore, which he brought out six years later, was printed in 8vo. The settings are here again in plain counterpoint, but this time the work contains the whole of the Church tunes. The title is as follows:—

The whole book of Psalms, collected into English metre by Sternhold Hopkins, &c. With the usual Hymns and Spiritual Songs, and all the ancient and modern tunes sung in Churches, composed in three parts, Cantus Medius and Bassus. In a more plain and useful method than hath been heretofore published. By John Playford. 1677.

Playford gives no reason for setting the tunes in three parts only, but we know that this way of writing was much in favour with English composers after the Restoration, and remained so till the time of Handel. Three-part counterpoint had been much used in earlier days by the secular school of Henry the Eighth's time, but its prevalence at this period was probably due to the fact that it was a favourite form of composition with Carissimi and his Italian and French followers, whose influence with the English school of the Restoration was paramount.

This was the last complete setting of the Church tunes, and for a hundred years afterwards it continued to be printed for the benefit of those who still remained faithful to the old melodies, and the old way of setting them. In 1757 the book had reached its 20th edition.

Playford generally receives the credit, or discredit, of having reduced the Church tunes to notes of equal value, since in his psalters they appear in minims throughout, except the first and last notes of sections, where the semibreve is retained; but it will be found, on referring to the current editions of Sternhold, that this had already been done, probably by the congregations themselves, and that he has taken the tunes as he found them in the authorized version. His settings also have often been blamed, and it must be confessed that compared with most of his predecessors, he is only a tolerable musician, though he thought himself a very good one; but this being admitted, he is still deserving of praise for having made, in the publication of his psalters, an intelligent attempt to assist in the general work of reconstruction; and if he failed to effect the permanent restoration of the older kind of psalmody, it was in fact not so much owing to his weakness, as to the natural development of new tendencies in the art of music.

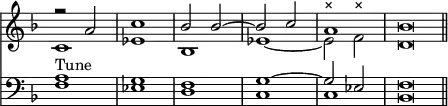

The new metrical translations afterwards brought out were always intended, like those of the Commonwealth, to be sung to the Church tunes; and each work usually contained a small selection, consisting of those most in use, together with a few new ones. Concurrently with these appeared a large number of publications,—Harmonious Companions, Psalm Singer's Magazines, etc., which contained all the favourite tunes, old and new, set generally in four parts. Through one or other of these channels most of the leading musicians of this and the following century contributed to the popular Psalmody. Both tunes and settings now became very various in character, and side by side with settings made for Este's Psalter might be found compositions of which the following fragment will give some idea.

Harmonious Companion, 1732.

![<< \time 3/2 \new Staff << \partial 2 \new Voice { \voiceOne \relative a' { a2 | g1 fis2 | g2. a4 b a | g1 g2 c1 \bar "||" } }

\new Voice { \voiceTwo \relative f' { f2 | d1 d2 | d e fis | d2. e4 f2 | g1 } } >>

\new Staff << \clef bass \new Voice = "tune" { \voiceOne \relative d' { d4(^"Tune" c) | b1 a2 | b4.^( c8 b4. c8) d4.^( c8) | b4.^( c8 b4. c8) d4^( b) | c8[ d] e2. } }

\new Voice { \voiceTwo d2 g1 d2 g1 d2 | g,1 g4 f | e8 d c2. } >>

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "tune" { The Lord goes up __ a -- bove __ the sky. } >>](../../I/fb69965c4e72269fb0488395d2dba3ef.png.webp)

On the next page is the original setting of the 44th Psalm by Blancks.

The fact most strongly impressed upon the mind after going through a number of these publications, extending over a period of one hundred and fifty years, is that the quality and character of the new tunes and settings in no way depends, as in the case of the old psalters, upon the date at which they were written. Dr. Howard's beautiful tune, St. Bride, for instance, was composed thirty or forty years after the strange production given above; his tune, however, must not be taken as a sign of any general improvement, things having rather gone from bad to worse. The truth seems to be that the popular tradition of psalmody having been hopelessly broken during the Commonwealth, and individual taste and ability having become the only deciding forces in the production of tunes, the composers of the 17th and 18th centuries, in the exercise of their discretion, chose sometimes to imitate the older style, and sometimes to employ the inferior methods of contemporary music. To the public the question of style seems to have been a matter of the most perfect indifference.

Sternhold continued to be printed as an authorized version until the second decade of the present century. The version of Tate and Brady remained in favour twenty or thirty years longer, and was only superseded by the hymnals now in actual use.[ H. E. W. ]

- ↑ 'Note' or 'note of song,' was, or rather had been, the usual description of music set to words. At this date it was probably old-fashioned, since it seldom occurs again. In 1544, Cranmer, in his letter to Henry VIII, respecting his Litany, speaks of the whole of the music sometimes as 'the note,' and sometimes as the 'song.'

- ↑ The unique copy of this book is in the library of Brasenose College, Oxford. Thanks are due to the College for permission to examine it.

- ↑ This was the usual way of printing the common measure in Crowley's day, and for many years afterwards.

- ↑ In the original the reciting note is divided into semibreves, one for each syllable.

- ↑ Except in that given by Warton, who speaks of several editions during Sternhold's lifetime; it is impossible however to corroborate this.

- ↑ The unique copy of this book is in the library of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Thanks are due to the College for permission to examine it.

- ↑ One of Tye's tunes has already been printed entire in this work. See article Windsor or Eton Tune.

- ↑ The unique copy of this book is in the Bodleian Library.

- ↑ The unique copy of this work is in the library of Christ Church, Oxford. Thanks are due to the College for permission to examine it.

- ↑ The unique copy of this book is in the Library of S. Paul's Cathedral. Thanks are due to the Dean and Chapter for permission to examine it.

- ↑ The imported tunes sometimes underwent a slight alteration, necessitated by the frequency of the feminine rhymes in the French version. By this method a new character was often given to the tune.

- ↑ The bars in the original are only sectional, coinciding with the punctuation of the text.

- ↑ A second edition was published in 1565.

- ↑ Causton, a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal, had been a contributor to 'Certayne notes.'

- ↑ He frequently converts passing discords into discords of percussion, by repeating the bass note; and his ear, it seems, could tolerate the prepared ninth at the distance of a second, when it occurred between inner parts.

- ↑ This passage, however, will present nothing extraordinary to those who may happen to have examined the examples, taken from Risby, Pigott, and others, in Morley's 'Plaine and Easle Introduction to Practicall Musick.' From those examples it appears that the laws which govern the treatment of discords were not at all generally understood by English musicians, even as late as the beginning of Henry the Eighth's reign: it is quite evident that discords (not passing) were not only constantly taken unprepared, but, what is more strange, the discordant note was absolutely free in its progression. It might either rise or fall at pleasure; it might pass, by skip or by degree, either to concord or discord; or it might remain to become the preparation of a suspended discord. And this was the practice of musicians of whom Morley says that 'they were skilful men for the time wherein they lived.'

- ↑ In Este's psalter the tune of No. 1 has already been altered, in order to make a true final close possible, in the manner shown below. The tune containing No. 2 does not occur again, but here also an equally simple alteration brings about the desired result.

1.

W. Cobbold.

2.

- ↑ W. Parsons must not be confounded with R. Parsons, a well-known composer of this period. J. Hake may possibly have been the 'Mr. Hake,' a singing man of Windsor, whose name was mentioned by Testwoode in one of the scoffing speeches for which he was afterwards tried (with Merbecke and another) and executed.

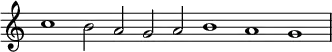

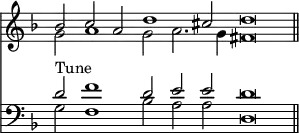

- ↑ Nothing is more interesting than to trace the progress of a passage of this kind through subsequent psalters, and to notice how surely, sooner or later, the modulation comes:—

Mode XIII. Transposed.

W. Cobbold (Este's Psalter, 1592).

T. Morley (Barley's Psalter).

- ↑ It must be confessed that the tune is more beautiful without its setting. Parsons has not only avoided every kind of modulation, but has even refused closes which the ear desires, and which he might have taken without having recourse to chromatic notes. It remained for later musicians to bring out the beauty of the melody.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 These works the writer has notbeen able to meet with.

- ↑ A second edition was published in 1594, and a third in 1604. The work was reprinted by the Musical Antiquarian Society in 1844.

- ↑ Farmer had published, in the previous year, forty canons, two in one, upon one plainsong. These however were only contrapuntal exercises.

- ↑ Johnson (Ps. cxl.) has taken the fourth unprepared in a chord of the 6-4, and the imperfect triad with the root in the bass. Farnaby so frequently abandons the old practice of making all the notes upon one syllable conjunct, that one must suppose he actually preferred the leap in such cases. The following variants of a well-known cadence, also, have a kind of interest, since it is difficult to see how they could for a moment have borne comparison with their original:—

G. Farnaby. E. Johnson.

Johnson, though sometimes licentious, was also sometimes even prudish. In taking the sixth and fifth upon the fourth of the scale, his associates accompanied them, in the modern way, with a third; Johnson however refuses this, and, following the strict Roman practice, doubles the bass note instead.

- ↑ It was by a chance more unfortunate even than usual that Dr. Burney selected this Psalter,—on the whole the best that ever appeared,—as a victim to his strange prejudice against our native music. His slighting verdict is that 'the book has no merit, but what was very common at the time it was printed': which is certainly true; but Allison, a musician of the first rank, is not deserving of contempt on the ground that merit of the highest kind happened to be very common in his day.

- ↑ Hawkins has evidently been misled by the clumsily worded title.

- ↑ One explanation only can be suggested at present. The work may never have been intended to rank with four-part psalters at all. The sole right to print Sternhold's version, with the church tunes, had just passed into the hands of the Stationers' company; and it is possible that this book may have been put forward, not as a fourth edition of Este, but in competition with the company: the promoters hoping, by the retention of the complete settings of a few favourite tunes, and the useless bass part of the rest, to create a technical difference, which would enable them to avoid infringement of the Stationers' patent. The new settings of Morley and Bennet may have been added as an attractive feature. If, however the announcement in the title of the third edition of Este (1604), 'printed for the companie of Stationers,' should mean that the company had acquired a permanent right to that work, Barley's publication would seem no longer to be defensible, on any ground. Further research may make the matter more clear.

- ↑ A second edition was published in 1633. It was also several times reprinted, either entirely or in part, during the 18th century.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 These works were reprinted by John Russell Smith in 1856 and 1872 respectively.