MELODY is the general term which is vaguely used to denote successions of single notes which are musically effective. It is sometimes used as if synonymous with Tune or Air, but in point of fact many several portions of either Tunes or Airs may be accurately characterised as 'melody' which could not reasonably be made to carry the name of the whole of which they form only a part. Tunes and airs are for the most part constructively and definitely complete, and by following certain laws in the distribution of the phrases and the balance of the groups of rhythms, convey a total impression to the hearer; but melody has a more indefinite signification, and need not be a distinct artistic whole according to the accepted laws of art, though it is obvious that to be artistic it must conform to such laws as lie within its range. For example, the term 'melody' is often with justice applied to the inner parts of fine contrapuntal writing, and examples will occur to every one in numerous choruses and symphony movements and other instrumental works where it is so perfectly woven into the substance of the work that it cannot be singled out as a complete tune or air, though it nevertheless stands out from the rest by reason of its greater beauty.

Melody probably originated in declamation through recitative, to which it has the closest relationship. In early stages of musical art vocal music must have been almost exclusively in the form of recitative, which in some cases was evidently brought to a very high pitch of expressive perfection, and no doubt merged into melody at times, much as prose in passages of strong feeling occasionally merges into poetry. The lowest forms of recitative are merely approximations to musical sounds and intervals imitating the inflexions of the voice in speaking: from this there is a gradual rise to the accompanied recitative, of which we have an example of the highest melodious and artistic beauty in the 'Am Abend da es kühle war,' near the end of Bach's Matthäus Passion. In some cases an intermediate form between recitative and tunes or airs is distinguished as an Arioso, of which we have very beautiful examples in Bach's 'Johannes Passion,' and in several of his Cantatas, and in Mendelssohn's 'Elijah.' Moreover we have opportunities of comparing mere declamatory recitative and melody in juxtaposition, as both Bach and Mendelssohn adopted the device of breaking into melody in especially solemn parts of recitative; as in No. 17 of the Matthäus Passion to the words 'Nehmet, esset,' etc., and in Nos. 41 and 44 in 'St. Paul,' near the end of each.

It appears then that recitative and melody overlap. The former, in proportion as it approximates to speech in simple narration or description, tends to be disjointed and unsystematised; and in proportion as it tends, on the other hand, towards being musically expressive in relation to things which are fit to be musically embodied, it becomes melody. In fact the growth of melody out of recitative is by assuming greater regularity and continuity and more appreciable systematisation of groups of rhythms and intervals.

The elements of effect in melody are extremely various and complicated. In the present case it will only be possible to indicate in the slightest manner some of the outlines. In the matter of rhythm there are two things which play a part the rhythmic qualities of language, and dance rhythms. For example, a language which presents marked contrasts of emphasis in syllables which lie close together will infallibly produce corresponding rhythms in the national music; and though these may often be considerably smoothed out by civilisation and contact with other peoples, no small quantity pass into and are absorbed in the mass of general music, as characteristic Hungarian rhythms have done through the intervention of Haydn, Schubert, Beethoven, and other distinguished composers. [See Magyar Music, p. 197.]

Dance-rhythms play an equally important part, and those rhythms and motions of sound which represent or are the musical counterpart of the more dignified gestures and motions of the body which accompany certain states of feeling, which, with the ancients and some mediæval peoples, formed a beautiful element in dancing, and are still travestied in modern ballets.

In the distribution of the intervals which separate the successive sounds, harmony and harmonic devices appear to have very powerful influence. Even in the times before harmony was a recognised power in music we are often surprised to meet with devices which appear to show a perception of the elements of tonal relationship, which may indicate that a sense of harmony was developing for a great length of time in the human mind before it was definitely recognised by musicians. However, in tunes of barbaric people who have no notion of harmony whatever, passages of melody also occur which to a modern eye look exceedingly like arpeggios or analyses of familiar harmonies: and as it is next to impossible for those who are saturated with the simpler harmonic successions to realise the feelings of people who knew of nothing beyond homophonic or single-toned music, we must conclude that the authors of these tunes had a feeling for the relations of notes to one another, pure and simple, which produced intervals similar to those which we derive from familiar harmonic combinations. Thus we are driven to express their melody in terms of harmony, and to analyse it on that basis: and we are moreover often unavoidably deceived in this, for transcribers of national and ancient tunes, being so habituated to harmonic music and to the scales which have been adopted for the purposes of harmony, give garbled versions of the originals without being fully aware of it, or possibly thinking that the tunes were wrong and that they were setting them right. And in some cases the tunes are unmercifully twisted into forms of melody to which an harmonic accompaniment may be adjusted, and thereby their value and interest both to the philosopher and to every musician who hears with understanding ears is considerably impaired. [See Irish Music.]

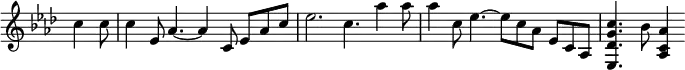

Modern melody is almost invariably either actually derived from, or representative of, harmony, and is dependent for a great deal of its effect thereupon. In the first place it is immediately representative in one of two ways; either as the upper outline of a series of different chords, and therefore representing changing harmonies; or else by being constructed of different notes taken from the same chord, and therefore representing different phases of permanent harmony. Examples of either of these forms being kept up for any length of time are not very common; of the first the largest number will be found among hymn tunes and other forms of simple note-against-note harmony;—the first phrase of 'Batti batti' approaches it very nearly, and the second subject of the first movement in Beethoven's Waldstein Sonata, or the first four bars of 'Selig sind die Todten' in Spohr's 'Die letzten Dinge' are an exact illustration. Of the second form the first subject of Weber's Sonata in A♭ is a remarkable example:—

since in this no notes foreign to the chord of A♭ are interposed till the penultimate of all. The first subject of the Eroica Symphony in like manner represents the chord of E♭, and its perfectly unadorned simplicity adds force to the unexpected C♯, when it appears, and to its yet more unexpected resolution; the first subject of Brahms's Violin Concerto is a yet further example to the point:—

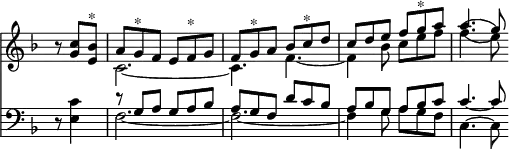

The simplest variation of these forms is arrived at by the interposition of passing notes between notes which are part of the essential chord or chords, as in the following from 'Cet asile aimable,' in Gluck's 'Orphée.'

The notes with asterisks may all be regarded as passing notes between the notes which represent the harmonies.

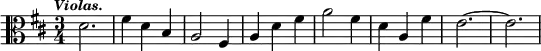

This often produces successions of notes which are next to each other in the scale; in other words, progression by single degrees, of which we have magnificent examples in some of the versions of the great subject of the latter part of Beethoven's 9th Symphony, in the first subject [App. p.716 "second subject of the first movement"] of his Violin Concerto, and in the last chorus of Bach's Matthäus Passion. When these passing notes fall on the strong beats of the bar they lead to a new element of melodic effect, both by deferring the essential note of the chord and by lessening the obviousness of its appearance, and by affording one of the many means, with suspensions, appoggiaturas, and the like, of obtaining the slurred group of two notes which is alike characteristic of Bach, Gluck, Mozart, and other great inventors of melody, as in the following example from Mozart's Quartet in D major:—

![<< \new Staff { \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \key g \major \partial 4 << \new Voice { \relative c'' { \stemUp \autoBeamOff \slurUp cis8[( d]) | e[( d]) d[( c!]) c[( b]) | d[( c]) c[( b]) b[( a]) | g4 } } \new Voice { \relative a' { \stemDown a4 | b r r | a r r | } } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key g \major << \new Voice { \relative f' { \stemUp fis8( d) | g4 s s | fis } } \new Voice { r4 g r r d r r g } >> } >>](../../I/95b074147dcd0ae0c5a8a12c9f1139a2.png.webp)

The use of chromatic preparatory passing notes pushes the harmonic substratum still further out of sight, and gives more zest and interest to the melodic outline; as an example may be taken the following from the 2nd Act of Tristan und Isolde.

![<< \new Staff { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \key ges \major << \new Voice { \relative b' { \stemUp bes4. ges8 ces,4 ~ | ces8 des ces'4. bes8 ~ | bes g aes4. ges8 ~ |

ges d ees g aes ces | ees4. ces!8 f,4 | ees'4. des!8 f,4 |

ees'8 d f,4. ges!8 ~ | ges g4 aes8 bes ces! | <bes d,>4. } }

\new Voice { \relative b { \stemDown bes2 a4 ~ | a8 bes ees4 eeses8 des | <ces f>2 <c g>4 | <ces aes>4 s2 | f2 s4 | f2 s4 | f4 s2 | ces4 c <ces des> | bes2 s8 } } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key ges \major << \new Voice { \stemUp des2 eeses4 | des4. ees8 f ges | s2. | s2 ees'4 ^~ | ees'2 d'4 | des'2 c'4 | ces'2 ^~ ces'8 bes | aes!4 ges f8 ees | des2 s8^"etc." }

\new Voice { \stemDown s2. s s s | s2 g8 aes | s2 g8 aes | s4 g8[ aes a bes] }

\new Voice { \stemDown ges,2. _~ ges, | des,( des2) c'8 aes | des2. _~ des _~ des _~ des g,2 } >> } >>](../../I/fd07f83e4c390119382ae6a175ba9d8b.png.webp)

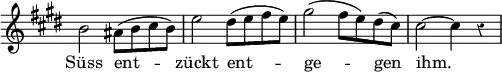

Along with these elements of variety there are devices of turns and such embellishments, such as in the beginning of the celebrated tune in Der Freischütz, which Agatha sings in the 2nd scene of the 2nd Act:—

Sequences also, and imitations and anticipations, and all the most elaborate devices of resolution, come into play, such as interpolation of notes between the discordant note and its resolution. Further, there are endless refinements of grouping of phrases, and repetition of rhythms and groups of intervals in condensed forms and in different parts of the scale, which introduce an intellectual element even into the department of pure melody.

Lastly, it may be pointed out that the order and character of the successions of harmony which any special form of melody represents has a great deal to do with its importance. Commonplace tunes represent commonplace and trite successions of harmony in a commonplace way, while melody of a higher order usually represents successions which are in themselves more significant and more freely distributed. The giants of art have produced tunes the melody of which may represent the simplest harmonic successions, but they do it in their own way, and the result is proportionate to their powers and judgment. Unfortunately, the material of the simpler order of melody tends to be exhausted, and a large proportion of new melody has to be constructed on a more complicated basis. To take simple forms is often only to make use of what the great masters rejected; and indeed the old forms by which tunes are constructively defined are growing so hackneyed that their introduction in many cases is a matter for great tact and consideration. More subtle means of defining the outlines of these forms are possible, as well as more subtle construction in the periods themselves. The result in both cases will be to give melody an appearance of greater expansion and continuity, which it may perfectly have without being either diffuse or chaotic, except to those who have not sufficient musical gift or cultivation to realise it. In instrumental music there is more need for distinctness in the outline of the subjects than in the music of the drama; but even in that case it may be suggested that a thing may stand out by reason of its own proper individuality quite as well and more artistically than if it is only to be distinguished from its surroundings by having a heavy blank line round it. Melody will always be one of the most important factors in the musical art, but it has gone through different phases, and will go through more. Some insight into its direction may be gained by examination of existing examples, and comparison of average characters at different periods of the history of music, but every fresh great composer who comes is sure to be ahead of our calculations, and if he rings true will tell us things that are not dreamed of in our philosophy.[ C. H. H. P. ]