FINGERING (Ger. Fingersatz, Applicatur; Fr. Doigté), the method which governs the application of the fingers to the keys of any keyed instrument, to the various positions upon stringed instruments, or to the holes and keys of wind instruments, the object of the rules being in all cases to facilitate execution. The word is also applied to the numerals placed above or beneath the notes, by which the particular fingers to be used are indicated.

In this article we have to do with the fingering of the pianoforte (that of the organ, though different in detail, is founded on the same principles, and will not require separate consideration); for the fingering of wind and stringed instruments the reader is referred to each particular name.

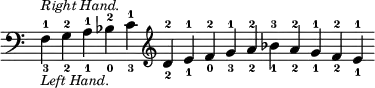

In order to understand the principles upon which the rules of modern fingering are based, it will be well to glance briefly at the history of those rules, and in so doing it must be borne in mind that two causes have operated to influence their development the—construction of the keyboard, and the nature of the music to be performed. It is only in comparatively modern times, in fact since the rise of modern music, that the second of these two causes can have had much influence, for the earliest use of the organ was merely to accompany the simple melodies or plainsongs of the church, and when in later years instrumental music proper came into existence, which was not until the middle of the 16th century, its style and character closely resembled that of the vocal music of the time. The form and construction of the keyboard, on the other hand, must have affected the development of any system of fingering from the very beginning, and the various changes which took place from time to time are in fact sufficient to account for certain remarkable differences which exist between the earliest rules of fingering and those in force at the present time. Until the latter half of the 16th century there would appear to have been no idea of establishing rules for fingering; nor could this have been otherwise, for from the time of the earliest organs, the keys of which were from 3 to 6 inches wide, and were struck with the closed fist, down to about the year 1480, when, although narrower, the octave still measured about two inches more than on the modern keyboard, any attempt at fingering in the modern sense must have been out of the question. The earliest marked fingering of which we have any knowledge is that given by Ammerbach in his 'Orgel oder Instrument Tabulatur' (Leipzig, 1571). This, like all the fingering in use then and for long afterwards, is characterised by the almost complete avoidance of the use of the thumb and little finger, the former being only occasionally marked in the left hand, and the latter never employed except in playing intervals of not less than a fourth in the same hand. Ammerbach's fingering for the scale is as follows, the thumbs being marked and the fingers with the first three numerals:—

This kind of fingering, stiff and awkward as it appears to us, remained in use for upwards of a century, and is even found as late as 1718, in the third edition of an anonymous work entitled 'Kurzen jedoch gründlichen Wegweiser,' etc. Two causes probably contributed to retard the introduction of a more complete system. In the first place, the organ and clavichord not being tuned upon the system of equal temperament, music for these instruments was only written in the simplest keys, with the black keys but rarely used; and in the second place the keyboards of the earlier organs were usually placed so high above the seat of the player that the elbows were of necessity considerably lower than the fingers. The consequence of the hands being held in this position, and of the black keys being but seldom required, would be that the three long fingers, stretched out horizontally, would be chiefly used, while the thumb and little finger, being too short to reach the keys without difficulty, would simply hang down below the level of the keyboard.

But although this was the usual method of the time, it is highly probable that various experiments, tending in the direction of the use of the thumb, were made from time to time by different players. Thus Praetorius says ('Syntagma Muaicum,' 1619), 'Many think it a matter of great importance, and despise such organists as do not use this or that particular fingering, which in my opinion is not worth the talk; for let a player run up or down with either first, middle, or third finger, aye, even with his nose if that could help him, provided everything is done clearly, correctly, and gracefully, it does not much matter how or in what manner it is accomplished.' One of the boldest of these experimenters was Couperin, who in his work 'L'art de toucher le clavecin' (Paris, 1717) gives numerous examples of the employment of the thumb. He uses it however in a very unmethodical way; for instance, he would use it on the first note of an ascending scale, but not again throughout the octave; he employs it for a change of fingers on a single note, and for extensions, but in passing it under the fingers he only makes use of the first finger, except in two cases, in one of which the second finger of the left hand is passed over the thumb, and in the other the thumb is passed under the third finger, in the very unpractical fashion shown in the last bar of the following example, which is an extract from a composition of his entitled 'Le Moucheron,' and will serve to give a general idea of his fingering.

About this time also the thumb first came into use in England. Purcell gives a rule for it in the instructions for fingering in his 'Choice Collection of Lessons for the Harpsichord,' published about 1700, but he employs it in a very tentative manner, using it only once throughout a scale of two octaves. His scale is as follows:—

Contemporary with Couperin we find Sebastian Bach, to whose genius fingering owes its most striking development, since in his hands it became transformed from a chaos of unpractical rules to a perfect system, which has endured in its essential parts to the present day. Bach adopted the then newly invented system of equal temperament for the tuning of the clavichord, and was therefore enabled to write in every key; thus the black keys were in continual use, and this fact, together with the great complexity of his music, rendered the adoption of an entirely new system of fingering inevitable, all existing methods being totally inadequate. Accordingly, he fixed the place of the thumb in the scale, and made free use of both that and the little finger in every possible position. In consequence of this the hands were held in a more forward position on the keyboard, the wrists were raised, the long fingers became bent, and therefore gained greatly in flexibility, and thus Bach acquired such a prodigious power of execution as compared with his contemporaries, that it is said that nothing which was at all possible was for him in the smallest degree difficult.

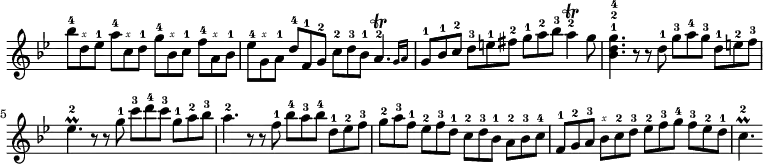

Our knowledge of Bach's method is derived from the writings of his son, Emanuel, who taught it in his 'Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen.' But it would not be safe to conclude that he gave it literally and without omissions. At any rate there are two small pieces extant, the marked fingering in which is undoubtedly by Sebastian Bach himself, and yet differs in several respects from his own rules as given by his son. These pieces are to be found in the 'Clavierbüchlein,' and one of them is also published as No. 11 of 'Douze petits Préludes,' but without Bach's fingering. The other is here given complete:—

In the above example it is worthy of notice that although Bach himself had laid down the rule, that the thumb in scale-playing was to be used twice in the octave, he does not abide by it, the scales in this instance being fingered according to the older plan of passing the second finger over the third, or the first over the thumb. In the fifth bar again the second finger passes over the first—a progression which is disallowed by Emanuel Bach.

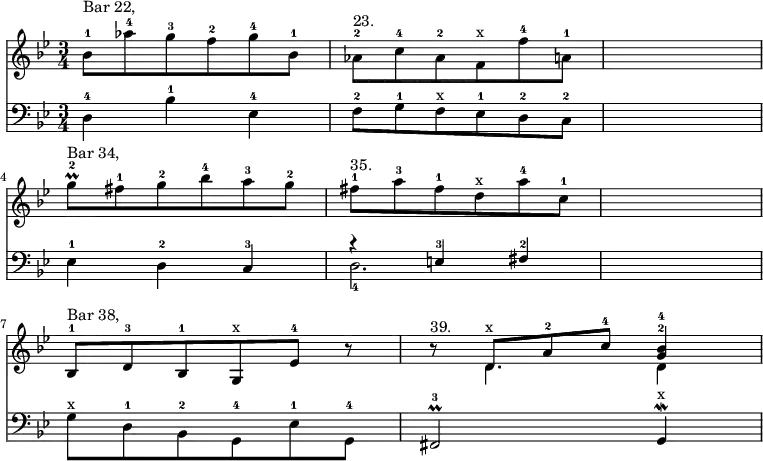

The discrepancies between Bach's fingering and his son's rules, shown in the other piece mentioned, occur between bars 22 and 23, 34 and 35, and 38 and 39, and consist in passing the second finger over the first, the little finger under the third (left hand), and the third over the little finger (left hand also).

From these discrepancies it would appear that Bach's own fingering was more varied than the description of it which has come down to us, and that it was free in the sense not only of employing every possible new combination of fingers, but also of making use of all the old ones, such as the passing of one long finger over another. Emanuel Bach restricts this freedom to some extent, allowing for instance the passage of the second finger over the third, but of no other long finger. Thus only so much of Bach's method has remained in practical use to the present lay as Emanuel Bach retained, and as is absolutely essential for the performance of his works.

Emanuel Bach's fingering has been practically that of all his successors until the most recent times; Clementi, Hummel, and Czerny adopted it almost without change, excepting only the limitation caused by the introduction of the pianoforte, the touch of which requires a much sharper blow from the finger than that of the clavichord or harpsichord, in consequence of which the gentle gliding of the second finger over the third, which was allowed by Emanuel Bach, has become unsuitable, and is now rarely used.

In the teaching of all the above-named masters, one principle is particularly observed,—the thumb is not used on a black key except (as Emanuel Bach puts it) 'in cases of necessity,' and it is the abolition of this restriction which forms the latest development of fingering. Modern composersn, and in particular Chopin and Liszt, have by their invention of novel passages and difficulties done once more for the thumb what Bach did for it, and just as he redeemed it from a condition of uselessness, so have they freed its employment from all rules and restrictions whatsoever. Hummel, in his 'Art of playing the Pianoforte,' says 'We must employ the same succession of fingers when a passage consists of a progression of similar groups of notes .... The intervention of the black key changes the symmetrical progression so far only as the rule forbids the use of the thumb on the black keys." But the modern system of fingering would employ absolutely the same order of fingers throughout such a progression without considering whether black keys intervene or no. Many examples of the application of this principle may be found in Tausig's edition of Clementi's 'Gradus ad Parnassum,' especially in the first study, a comparison of which with the original edition (where it is No. 16) will at once show its distinctive characteristics. That the method has immense advantages and tends greatly to facilitate the execution of modern difficulties cannot be doubted, even if it but rarely produces the striking result ascribed to it by Von Bülow, who says in the preface to his edition of Cramer's Studies, that in his view (which he admits may be somewhat chimerical), a modern pianist of the first rank ought to be able by its help to execute Beethoven's 'Sonata Appassionata' as readily in the key of F♯ minor as in that of F minor, and with the same fingering!

There are two methods of marking fingering, one used in England and the other in all other countries. Both consist of figures placed above the notes, but in the English system the thumb is represented by a ×, and the four fingers by 1, 2, 3, and 4, while in Germany, France, and Italy, the first five numerals are employed, the thumb being numbered 1, and the four fingers 2, 3, 4, and 5. This plan was probably introduced into Germany—where its adoption only dates from the time of Bach—from Italy, since the earliest German fingering (as in the example from Ammerbach quoted above) was precisely the same as the present English system, except that the thumb was indicated by a cypher instead of a cross. The same method came into partial use in England for a short time, and may be found spoken of as the 'Italian manner of fingering' in a treatise entitled 'The Harpsichord Illustrated and Improv'd,' published about 1740. Purcell also adopted it in his 'Choice Collection' quoted above, but with the bewildering modification, that whereas in the right hand the thumb was numbered 1, and so on to the little finger, in the left hand the little finger was called the first, and the thumb the fifth.[ F. T. ]