BALLAD, from the Italian ballata,[1] a dance, and that again from ballare, to dance. The form and application of the word have varied continually from age to age. In Italy a Balletta originally signified a song intended to be sung in dance measure, accompanied by or intermixed with dancing; 'in the Crusca dictionary,' says Burney, 'it is defined as Canzone, che si canta ballando'—a song sung while dancing. The old English ballads are pieces of narrative verse in stanzas, occasionally followed by an envoi or moral. Such are 'Chevy Chase,' 'Adam Bell, Clym of the Clough and William of Cloudeslee,' 'The Babes in the Wood'; and, to come to more modern times, such are 'Hozier's Ghost' (Walpole's favourite), Goldsmith's 'Edwin and Angelina,' and Coleridge's 'Dark Ladie.' But the term has been used for almost every kind of verse—historical, narrative, satirical, political, religious, sentimental, etc. It is difficult to discover the earliest use of the word. Many references which have been made to old authors reputed to have employed it are not to the point, as it will be found in such cases that the original word in the old Latin chronicles ia some form of the noun 'cantilena.'

In a MS. of the Cotton collection, said to be as ancient as the year 1326, mention is made of ballads and roundelays (Hawkins, Hist. of Music). John Shirley, who lived about 1440, made a collection of compositions by Chaucer, Lydgate, and others, and one of the volumes, now in the Ashmolean collection, is entitled 'A Boke cleped the abstracte brevyaire, compyled of diverse balades, roundels, … collected by John Shirley.' In the devices used at the coronation of Henry VI (Dec. 17, 1431) the king was portrayed in three several ways, each 'with a ballad' (Sharon Turner). Coverdale's Bible, printed in 1535, contains the word as the title of the Song of Solomon 'Salomon's Balettes called Cantica Canticorum.'

Ballad making was a fashionable amusement in the reign of Henry VIII, who was himself renowned for 'setting of songes and makyng of ballettes.' A composition attributed to him, and called 'The Kynges Ballade' (Add. MSS. Brit. Mus. 5665), became very popular. It was mentioned in 'The Complainte of Scotland,' published in 1548, and also made the subject of a sermon preached in the presence of Edward VI by Bishop Latimer, who enlarged on the advantages of 'Passetyme with good companye.' Amongst Henry's effects after his decease, mention is made of 'songes and ballades.' In Queen Elizabeth's reign ballads and ballad gingers came into disrepute, and were made the subject of repressive legislation. 'Musicians held ballads in contempt, and great poets rarely wrote in ballad metre.'

Morley, in his 'Plaine and easie introduction to Practicall Musicke,' 1597, says, after speaking of Vilanelle, 'there is another kind more light than this which they tearm Ballete or daunces, and are songs which being sung to a dittie may likewise be danced, these and other light kinds of musicke are by a general name called aires.' Such were the songs to which Bonny Boots, a well-known singer and dancer of Elizabeth's court, both 'tooted it' and 'footed it.' In 1636 Butler published 'The Principles of Musicke,' and in that work spoke of 'the infinite multitude of Ballads set to sundry pleasant and delightful tunes by cunning and witty composers, with country dances fitted unto them.' After this the title became common.

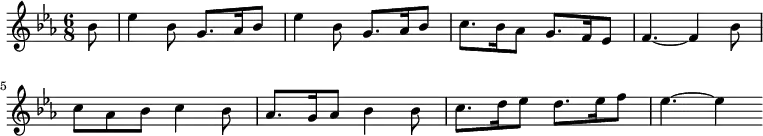

The name has been applied to a pastoral song, 'Sumer is icumen in,' preserved in the Harleian MSS., which dates from the 13th century, and furnishes the earliest example known (though it is obvious that so finished a composition cannot have been the first) of part music. The music is in triple measure, and a sort of dance rhythm, but the song can in no sense be called a ballad. [See Sumer is icumen in.] The music of many real old ballads has however survived, for which the reader may be referred to Mr. W. Chappell's well-known work. 'Chevy Chase' appears to have been sung to three different melodies. One of these, 'The hunt is up,' was a favourite popular air, of which we give the notes—

This old tune was otherwise employed. In 1537 information was sent to the Council against John Hogon, who, 'with a crowd or a fyddyll,' sang a song with a political point to the tune 'The hunt is up.' 'If a man,' says Fletcher of Saltoun, 'were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care who should make the laws of a nation.' 'Lilliburlero' (beloved of my uncle Toby), is a striking proof of the truth of Saltoun's remark, since it helped to turn James II out of Ireland. The tune and the history of the song will be found under Lilliburlero. 'Marlbrouk,' the 'Marseillaise,' and the 'Wacht am Rhein,' are other instances of ballads which have had great political influence.

Ballads have sunk from their ancient high estate. Writing in 1803 Dr. Burney said, 'A ballad is a mean and trifling song such as is generally sung in the streets. In the new French Encyclopédie we are told that we English dance and sing our ballads at the same time. We have often heard ballads sung and seen country dances danced; but never at the same time, if there was a fiddle to be had. The movement of our country dances is too rapid for the utterance of words. The English ballad has long been detached from dancing, and, since the old translation of the Bible, been confined to a lower order of song.' Notwithstanding the opinion of Dr. Burney the fact remains incontrovertible that the majority of our old ballad tunes are dance tunes, and owe their preservation and identification to that circumstance alone—the words of old ballads being generally found without the music but with the name of the tune attached, the latter have thus been traced in various collections of old dance music. The quotation already made from Butler shews that the use of vocal ballads as dance tunes implied in the name had survived as late as the reign of Charles I. One instance of the use of the word where dancing can by no possibility be connected with it is in the title to Goethe's 'Erste Walpurgisnacht,' which is called a Ballad both by him and by Mendelssohn, who set it to music. The same may be said of Schiller's noble poems 'Der Taucher,' 'Ritter Togenburg,' and others, so finely composed by Schubert, though these are more truly 'ballads' than Goethe's 'Walpurgisnacht.' So again Mignon's song 'Kennst du das Land,' though called a 'Lied' in Wilhelm Meister, is placed by Goethe himself at the head of the 'Balladen' in the collected edition of his poetry. In fact both in poetry and music the term is used with the greatest freedom and with no exact definition.

At the present time a ballad in music is generally understood to be a sentimental or romantic composition of a simple and unpretentious character, having two or more verses of poetry, but with the melody or tune complete in the first, and repeated for each succeeding verse. 'Ballad concerts' are ostensibly for the performance of such pieces, but the programmes often contain songs of all kinds, and the name is as inaccurate as was 'Ballad opera' when applied to such pieces as 'The Beggar's Opera,' which were made up of well-known airs with fresh words. [English Opera.][ W. H. C. ]

[ M. ]

- ↑ Ballata = a dancing piece, as Suonata, a sounding piece, and Cantata, a singing piece.