SEALS. The idea of testifying the personal presence or the agency of an individual on some particular occasion, by affixing the impression of his seal (Lat. sigillum, O. Fr. scel) to the record or object connected with the transaction of the moment, can be traced back among the nations of the old world when advanced only a comparatively short way on the path of civilization. In the East the custom which has prevailed for centuries, and which is a practice at the present day, of using the seal as a stamp wherewith to print its device in ink or pigment in authentication of a document is parallel to our western habit of inscribing a signature for the same purpose. In the West, too, the impression of the seal has, at certain periods, had the same value as the signature; and at all times the connexion between the signature and the seal has been intimate in European practice (see Autographs and Diplomatic). But the western method of obtaining the impression has differed from the eastern method. With us, the notion of a seal is an impression in relief, obtained from an incised design, either on a soft material such as wax or clay, or on a harder material such as lead, gold or silver. By common usage the word “seal,” is employed as a term to describe both the implement for making the impression, and the impression itself; but properly it should be confined to the latter, the graven implement being technically called the matrix.

The earliest examples of seals, both matrices and impressions, are found among the antiquities of Egypt, Babylonia and Assyria. On the clay stoppers of wine jars of the remote age which goes by the name of the pre-dynastic period, and which preceded the historic period of the Egyptian seals. first Pharaohs, there are seal impressions which must have been produced from matrices, like those of Babylonia and Assyria, of the cylinder type, the impress of the design having been repeated as the cylinder was rolled along the surface of the moist clay. Two such engraved cylinders of this archaic period are in the British Museum collections. The cylinder, however, seems to have been generally superseded in Egypt by the engraved scarab, or beetle-shaped object, which, it may be assumed, was used at an early time, as it certainly was in later Egyptian history, for sealing purposes, although its proper function was that of an amulet. Still, the fashion for cylinders appears to have revived at intervals, for they are found in the 6th, the 12th and the 18th dynasties. Even in the 1st dynasty, about 4500 B.C., the Egyptian Pharaohs had their official sealers, or, to use a modern expression, keepers of the Royal Seal. Egyptian signet rings, which were used for sealing, date back to the 12th dynasty.

As already stated, the matrices of ancient Babylonian and Assyrian seals, usually cut on precious stones, are in cylinder form. The fine collection in the British Museum presents us with Babylonian specimens of even archaic times, followed by an historical series, the earliest of which Babylonian and Assyrian seals. is of nearly 4500 years B.C. The Assyrian series is not so full. The engraved subjects are chiefly mythological. Impressions are to be found on many of the cuneiform clay tablets. Early in the 7th century B.C. the cylinder seal gave place to the cone, the impression being henceforth obtained after the fashion followed to the present day.

The Phoenicians, as was only to be expected of those traders and artisans of the ancient world, appear to have adopted both the cylinder of Assyria and the scarab of Egypt as patterns for their seals. Examples indeed are rare, but that these people were acquainted with both Phoenician seals. forms is certain. Phoenician names are found cut both on cylinder matrices and on scarabs by the Phoenician engravers employed in Assyria and Egypt; and, when the cone-shaped matrix superseded the cylinder in Western Asia, the Phoenicians conformed to the change.

In Europe, the use of seals among the early Greeks is well known. Of the Mycenaean period numerous seal-impressions in clay have been found. Also from ancient times have survived the numerous engraved stones or pebbles, technically called gems, which served as Greek seals. matrices and in most instances were undoubtedly mounted as finger-rings or were furnished with swivels. At first being used in their natural forms, these pebbles or gems have been grouped as lenticular or bean-shaped, and glandular or of the sling-bolt pattern; later, from the 6th to the 4th century B.C., they were fashioned as scaraboids, that is, in the general form of the Egyptian scarab, but without the sculptured details of the beetle's body. To these, by a natural process, succeeded the matrix formed of only a thin slice of stone, which was more conveniently adapted for the bezel of the ring; and in this shape the engraved matrix passed on from the Greeks to the Romans. Signet-rings also with fixed metal bezels were in common use among the Greeks from about 600 B.C.

But while the scarab met with little favour in Greece, where, as just stated, the scaraboid was preferred, among the Etruscans its adoption was complete, and with them it became the commonest form of the seal-matrix, dating from the latter part of the 6th centuryEtruscan seals. B.C., engraved chiefly with subjects derived from Greek art.

Impressions of late Greek or Roman gems in clay have survived in a few instances. A series of impressions from Greek seals was found at Selinus in Sicily, dating before 249 B.C.; a small collection of sealed Greek documents on papyrus of the 4th and 3rd centuries B.C. has been discovered at Elephantine in Egypt. An interesting and very rare example of a Roman law deed sealed with gem impressions in clay is in the British Museum, recording the sale of a slave boy in A.D. 166.

It is not the object of this article to deal further with the history of antique seals (see Numismatics; also Gems, Jewelry and Ring), but to give some account of European seals of the middle ages, when the revival of their use for the authentication of documents resulted in their universal employment among all classes of society. Hence it is that We are in possession of the vast number of impressions still to be found in public museums and archives, and in private muniment rooms and antiquarian collections, either attached to the original charters or other deeds which they authenticated, or as independent specimens. Hence, too, have survived a fairly large number of matrices.

The connecting link between the general use of the signet, which was required by the Roman law for legal purposes, but which had died out by the 7th century, and the revival of seals in the middle ages is to be found in the chanceries of the Merovingian and Carolingian sovereigns, where Early medieval seals. the practice of affixing the royal seal to diplomas appears to have been generally maintained (see Diplomatic). Naturally, surviving examples of such seals are rare, but they are sufficient in number to indicate the style adopted at different periods. The seal-ring of Childeric II. (d. 673) was found in his tomb, bearing a full-face bust and his name; and impressions of seals of later monarchs of the Merovingian line, engraved with their busts and names, have survived. Pippin the Short and the early Carolings made use of intaglios, both actual antiques and copies from them; their successors had seals of ordinary types usually showing their busts. One of the oldest matrices is an intaglio in rock crystal, now preserved at Aix-la-Chapelle, bearing a portrait head of Lothair II., king of Lorraine (A.D. 855–869), and the legend “Xp̄e [Christe] Adivva Hlotharium Reg.” As time advanced there was a growing tendency to enlarge the royal seal. Under Hugh Capet there was (A.D. 989) a further development, the king being represented half-length with the royal insignia; and at last under Henry I. (A.D. 1031–1060) the royal seal of France was complete as the seal of majesty, bearing the full effigy of the king enthroned. In Germany, however, this full type had already been attained somewhat earlier in the seal of the emperor Henry II. (A.D. 1002–1024); and it had been used even earlier by Arnulf, count of Flanders, in 942. The royal seal thus developed as a seal of majesty became the type for subsequent seals of dignity of the monarchs of the middle ages and later, the inscription or legend giving the name and titles of the sovereign concerned.

All the early royal seals which have been referred to were affixed to the face of the documents, that is, en placard; but in the 11th century the practice of appending the seal from thongs or cords came into vogue; by the 12th century it was universal. Naturally, the introduction of the pendant seal invited an impression on the back as well as on the face of the disk of wax or other material employed. Hence arose the use of the counterseal, which might be an impression from a matrix actually so called (contrasigillum), or that of a signet or private seal (secretum), such counter sealing implying a personal corroboration of the sealing. The earliest seal of a sovereign of France to which a counter seal was added was that of Louis VII. A.D. 1141), an equestrian effigy of the king as duke of Aquitaine being impressed on the reverse. When, in 1154, Aquitaine passed to the English crown, this counter seal disappeared, and eventually in subsequent reigns a fleur-de-lis or the shield of arms of France took its place. In the German royal seals the imperial eagle or the imperial shield of arms was the ordinary counterseal.

|

| Fig. 1.—Seal of Edward the Confessor. |

To turn to England: it appears that the kings of the Anglo-Saxon race, or at least some of them, imitated their Frankish neighbours in using signets or other seals. There are still extant an impression of the seal of Offa of Mercia A.D. 790) bearing a portrait head; and one of the seal of Anglo-Saxon royal seals. Edgar A.D. 960), an intaglio gem. The first royal seal of England which ranks as a “great seal” is that of Edward the Confessor, impressions of which are extant. This seal was furnished with a counterseal, the design being nearly identical with that of the obverse (fig. 1). William the Conqueror, as duke of Normandy, used an equestrian Great seals. seal, representing him mounted and armed for battle. After the conquest of England, he added a seal of majesty, copied from the seal of Henry I. of France, as a counterseal. In subsequent reigns the order of the two seals was reversed, the seal of majesty becoming the obverse, and the reverse being the equestrian seal: a pattern which has been followed, almost uniformly, down to the present day.

Besides the two royal seals of Anglo-Saxon kings noticed above there are extant a few other seals, and there is documentary evidence of yet others, which were used in England before the Norman Conquest; but the rarity of such examples is an indication that the Anglo-Saxon private seals. employment of seals could not have been very common among our Anglo-Saxon forefathers. Berhtwald the thane, in 788, and Æthelwulf of Mercia, in 857, affixed their seals to certain documents. In the British Museum are the bronze matrices of seals of Æthilwald, bishop of Dunwich, about 800; of Ælfric, alderman of Hampshire, about 985; and the finely carved ivory double matrix of Godwin the thane (on the obverse) and of the nun Godcythe (on the reverse), of the beginning of the 11th century. In the Chapter Library of Durham there is the matrix of the monastic seal of about the year 970; and in the British Museum, appended to a later charter (Harl. 45 A. 36), is the impression of the seal of Wilton Abbey of about 974.

The official practice of the Frankish kings, which, as we have seen, was the means of handing down the Roman tradition of the use of the signet, was gradually imitated by high officers of state. In the 8th century the mayors of the palace are found affixing their personal seals to royal Medieval seals. diplomas; and, once the idea was started, the multiplication of seals naturally followed. From the end of the 10th century there was a growing tendency to their general use. From the 12th to the 15th century inclusive, sealing was the ordinary process of authenticating legal documents; and during that period an infinite variety of seals was in existence. The royal seals of dignity or great seals we have already noticed. The sovereign also had his personal seals: his privy seal, his signet. The provinces, the public departments, the royal and public officers, the courts of law: all had their special seals. The numerous class of ecclesiastical seals comprised episcopal seals of all kinds, official and personal; seals of cathedrals and chapters; of courts and officials, &c. The monastic series is one of the largest, and, from an artistic point of view, one of the most important. The topographical or local series comprises the seals of cities, of towns and boroughs and of corporate bodies. Then come the vast collections of personal seals. Equestrian seals of barons and knights; the seals of ladies of rank; the armorial seals of the gentry; and the endless examples, chiefly of private seals, with devices of all kinds, sacred and profane, ranging from the finely engraved work of art down to the roughly cut merchant's mark of the trader and the simple initial letter of the yeoman, typical of the time when everybody had his seal.

The ordinary shape of the medieval seal is round; but there are certain exceptions. Ladies' seals and some classes of ecclesiastical and monastic seals are of pointed oval form, which is best adapted to receive the standing figure of lady, bishop, abbot or saint: the common types in Shapes.such classes. Fancifully shaped seals also occur, but they are comparatively rare.

|

| Fig. 2.—Antique gem used as a private seal. |

In the middle ages the metal chiefly employed in the manufacture of matrices was bronze. Among the wealthy, silver was not uncommon; among the poor, lead was in general use. Matrices of steel and iron were made at a later time in the 16th and 17th centuries. In the 11th century a fairly large Matrices. number of matrices were cut in ivory. The use of engraved gems in the early middle ages has already been noticed; but the taste for antique intaglios was not confined to any one period. In the later centuries also, particularly in the 14th century, they were set in seal matrices and finger rings. A fine Graeco-Roman gem, bearing a female head, full face and set in a medieval setting, does duty for the head of Mary Magdalen, as seen in the accompanying cut (fig. 2).

|

| Fig. 3.—Seal of Boxgrave Priory: obverse. |

The ordinary matrix of the middle ages was provided with a ridge on the back (or, in some instances, with a vertical handle), by which it could be held while being used for sealing, and which might be pierced for suspension. Sockets for the insertion of handles are of comparatively late make. The matrix was in most instances simple, the design giving a direct impression once and for all. But there are examples of elaborate matrices composed of several pieces, from the impressions of which the seal was built up in an ingenious fashion, both obverse and reverse being carved in hollow work, through which figures and subjects impressed on an inner layer of wax are to be seen. Such examples are the seal matrix of the Benedictine priory of St Mary and St Blaise of Boxgrave in Sussex, of the 13th century, now in the British Museum (fig. 3); and the matrix of Southwick Priory in Hampshire, of the same period (Archaeologia, xxiii. 374). The matrix of one of the seals of Canterbury Cathedral was also constructed in the same manner.

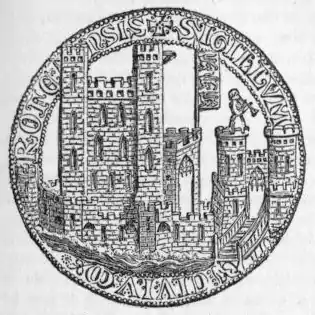

It has usually been the custom to break up or deface the matrices of official seals when they have ceased to be valid, as, for example, at the commencement of, a new reign. The seals of deceased bishops or abbots were solemnly broken in presence of the chapter or before the altar. But the legal maxim that corporations never die is well illustrated by the survival of the fine series, not-complete, indeed, but very full, of the matrices of English corporations, beginning with the close of the 12th century. A fine example is the corporate seal of Rochester, of the 13th century, showing the keep and battlements of the castle (fig. 4) in high relief.

The common material for receiving the impressions from the matrices was beeswax, generally strengthened and hardened by admixture with other substances, such as resin, pitch and even hemp and hair. The employment of chalk as an ingredient in many seals Waxen impressions. of the 12th century has caused them to become extremely friable. It was a common practice to apply to such seals a coating of brown varnish. Besides the transparent yellowish-brown of the wax when used in its natural state, as it very frequently was used in the earlier middle ages, many other colours, especially red, dark green and dark brown, and even black, are found in medieval seals. Any attempt to classify examples by their colours fails, for, while at some periods the particular tints employed in certain chanceries may have been selected with a view to marking the character of the documents so sealed, such practice was not consistently followed.

|

| Fig. 4.—Corporate Seal of Rochester. |

For the protection of the impression, in the 12th and 13th centuries, when it was an ordinary custom to impress the seals on thick cakes of wax, the surrounding margin rising well above the field usually formed a suitable fender; at other times, as in the 14th and 15th centuries, a so-called wreath, or twisted shred of parchment, or plaited grass or reed, was imbedded in the wax round the impression. But the most common process was to sew up the seal in a bag or piece of cloth or canvas, with the mistaken notion that this would ensure the seal’s integrity; the ordinary result being that, on the assumption that seals thus protected needed no further care, they have been in most instances either broken or crushed to powder. In later times, seals, especially great seals, have been frequently fitted in metal or wooden boxes.

The medieval seal may be said, in general, to be composed of two essential parts: the device, or type as it is sometimes called, and the inscription or legend. It is the existence of the legend, surrounding the device as with a border, that distinguishes it from the antique engraved gem, which rarely bore an Type and legend. inscription and then only its field. Such antique gems as were adopted for matrices in the middle ages were usually set in metal mounts, on which the legends were engraved. The first and obvious reason for an inscription on a seal was to ensure identification of the owner; and therefore the names of such owners appear in the earliest examples. Afterwards, when the use of seals became common, and when they were as often toys as signets, fanciful legends or mottoes appropriate to the devices naturally came into vogue. Examples of such mottoes will be given below.

A few words may be said regarding the different kinds of types or devices appropriate to particular classes or groups of medieval seals; and, although these remarks have special reference to English seals, it may be noted that there is a common affinity between the several classes of seals of all countries of western Europe, and that what is said of the seal-devices of one country may be applied in general terms to those of the rest. The types of the great seals of sovereigns have already been mentioned: a seal of majesty on the obverse, an equestrian seal on the reverse. Other royal official seals usually bear on the obverse the king enthroned or mounted, and the royal arms on the reverse.

|

| Fig. 5.—Seal of Lord High Admiral Huntingdon. |

Among other official seals a very interesting type is that of the Lord High Admiral in the 15th century, several matrices of the seals of holders of the dignity having survived and being exhibited in the British Museum. That of John Holland, earl of Huntingdon, Admiral of England, Ireland and Aquitaine, 1435–1442, is here given (fig. 5), having the usual device of a ship, on the mainsail of which are the earl’s armorial bearings. In ecclesiastical seals generally, in the seals of religious foundations, cathedrals, monasteries, colleges and the like, sacred subjects naturally find a place among other designs. Such subjects as the Deity, the Trinity, the Annunciation, the Nativity, the Crucifixion, the Coronation of the Virgin, are not uncommon. Episcopal seals more generally show the prelate prominently as a standing figure, or, less conspicuously, as kneeling in prayer before the Deity or patron saint; the counterseal also frequently represents him in the same posture of adoration. Chapter seals may bear the patron saint, or a representation, more or less conventional, of the cathedral; monastic seals may have figures of the Virgin Mary, or other patron saint, or of the founder, or of abbot or abbess; or the conventual building. If there be a counterseal, the figure of patron saint or founder may stand there, while the building occupies the obverse. Each abbot, too, would have his own seal of dignity, generally showing him standing. Local seals of town or borough may have the image of a patron saint, or armorial device, or castle or bridge or other building (see fig. 4), or the town itself. A seaport will be indicated by a ship on the waves. The baronial seal bears the armed and mounted knight. On ladies’ seals the owner is often gracefully depicted standing and holding flower or bird, or with shields of arms. After the 14th century, the figures of ladies, other than queens, vanish from seals. Armorial devices of the gentry first appear on seals at the close of the 12th century; and from that time there is a gradual development of the heraldic seal, which in the 14th century was often a work of fine decorative sculpture. And, lastly, the devices on fancy seals are without end in their variety.

|

| Fig. 6.—Merton Priory Seal. |

As in all other departments of medieval art, the engraving of seals in the middle ages passed through certain well-marked developments and changes characteristic of different periods. Fine seal engraving is to be found in the productions of many of the continental nations; but in the best Art. periods nothing can excel the work of English cutters. Beginning with the examples of the 11th and 12th centuries, we find the subjects generally of an archaic style, which is evidence of an early stage of the art. In the 13th century this undeveloped stage has passed, and a fine, but still restrained, quality of engraving ensues, which, like all the allied arts of that century, charms with its simple and unpretending precision. For example, in the great seals of Henry III., something of the antique stiffness remains, but the general effect and the finish of the details are admirable. We may refer also again to the Boxgrave seal (fig. 3) as a fine specimen of 13th century architectural carving.

|

| Fig. 7.—Seal of Robert Fitz-Walter. |

But the most beautiful seal of this period, and in many respects the most beautiful medieval seal in existence, is the monastic seal of Merton Priory, in Surrey, of the year 1241. An engraving of the obverse, the Virgin and Child, is here given (fig. 6). The Merton seal is the work of a master hand treating his subject with wonderful breadth and freedom. As the century advances, a more graceful movement in the figures is discernible. For instance, the great seal of Edward I. shows a departure from the severe simplicity of his predecessor in the addition of decorative architectural details, and in the easier action of the equestrian figure, which in this instance is of a strikingly fine type. Comparable with it is the remarkable baronial equestrian seal of Robert Fitz-Walter (fig. 7), 1298–1304, the silver matrix of which is in the British Museum collections.

The work of the 14th century is marked by a great development in decoration. Where the artist of the former century would have secured his effect by simple, firm lines, the new school trusted to a more superficial style, in which ornament rather than form is the leading motive. The new style is conspicuous in the great seals and other official seals of Edward III., as well as in other classes. The 14th century is also the period of enriched canopies, of niches and pinnacles and of other details of monumental sculpture reproduced in its seals. A very beautiful and typical example of the best work of this period of Richard de Bury, bishop of Durham from 1333 to 1345 (fig. 8).

|

| Fig. 8.—Seal of Richard de Bury, late 14th century. |

It is to be remarked that the standing figure of the bishop in episcopal seals, of the abbot in monastic seals and, of the lady in ladies’ seals, which was so persistent from the 12th century onwards, proved to be the happy cause of the maintenance of the elegant oval shape in examples of these classes, wherein some of the best balanced designs are to be found.

The 15th century brought with it to seal-engraving, as it did to other departments of medieval art, the elements of decadence. The execution becomes of a more mechanical type; the strength of the 13th century and the gracefulness of the 14th century have passed; and, while examples of great elaboration were still produced, the tendency grows to overload the decoration. This defect is noticeable for example, in the elaborate great seals of the Henries of the 15th century, as compared with the finer types of their predecessors. As a good example of the middle of the century, the seal of King’s College, Cambridge, of about the year 1443, is here given (fig. 9), showing the Virgin in glory in the centre, between St Nicholas and King Henry VI.

|

| Fig. 9.—Seal of King’s College, Cambridge. |

With the rise of the period of the Renaissance, like other medieval arts, seal-engraving passed out of the range of the traditions of the middle ages and came under the influence of the derived classical or pseudo-classical sentiment. There is, therefore, no need to pursue the subject further.

We close this portion of the present article with specimens of the legends or mottoes which are to be found on the innumerable personal seals of the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries. They are of great variety, and many of them are very interesting, both on account of the devices which they accompany Mottoes. and the sentiments which they express. In English seals they are found composed in Latin, in French, and in the vernacular. First there are legends describing the quality of the seal or conveying a message to the recipient of the missive, as:—Privé su (suis); privé su et poi conu (peu connu); sigillum secreti; secreti nuntius; je su mute; lel (loial) ami muet; je su sel bon e leel; veici parti lel; clausa secreta tego; signo secreta signo; secreta gero; si frangis, revelo; frange, lege, tege; brusset, liset, et celet; accipe, frange, lege; claude, repone, tege; missa lege, lecta tege; tecta lege, lecta tege; briset, vaez, lisez, craez; tene fidem; tenet la foy; softe and fayre. Seals with love mottoes are numerous:—sigillum pacis et amoris; je suy damurs; je su seel damur lel; seel de saluz e damur; de li penset par ki me avet; jeo su ci en lu dami; penset de li par ki su ci; ase for the treweste; ami amet, car lel ami avet; amye amet, mon quer avet; mun quer avet, ben le gardé; mun cuer avet, ne le deceve; penset de moi, e je de vus; mon quer jolye a vos doin, amye; je suy flur de lel amur; love me and I the; if the liket, mi love holde; poi vaut vivre sans lel ami. The lion is a not uncommon device:—Je su lion bon par avisoun; sum leo, quovis eo, non nisi uera veho; je su rey des bestes, leo tegit secretum. A lion dormant:—Ci repose le lion; ici dort le lion fort; wake, me no man. A lion dormant on a rose, the symbol of secrecy:—Ben pur celer, gis sur roser; ici repose liun en la rose; de su la rose le lion repose. Rustic life is represented by a squirrel:—I crake notis; I krak nots; I bite notes: by a hare, or a hare riding a dog:—Sohou, sohou; sohou, mutel; sohou, Robin; sohou, je le voi; sohou, je lai trouvé; je vois a bois; by a hare in a tree:—Sohou, scut, ware I cut: by a monkey riding a dog or goat:—Allone I ride, I hunt; allone I ride, have I no swayn: by a stag:—Alas, Bowles: by a dog:—hobbe, dogge, hobbe; garez ben le petit chen: by a hawk seizing a bird:—Alas, je su pris. And more than one example bears the motto:—By the rood, women ar wood (mad).

Bullae.—As stated above, metal seals, as well as seals in soft materials, have been employed in European countries under certain conditions. These are technically called “bullae” (Lat. bulla, a boss, or circular metal ornament), and necessarily they were in all cases suspended from the documents, and they bore a design on both obverse and reverse. In the southern countries of Europe, where wax would be affected by the warmth of the climate, it was natural that a harder material should also be used. Hence the leaden bulla was a recognized form of seal during the middle ages in the Peninsula, in southern France, in Italy, and in the Latin East. The best-known series is the papal series of leaden seals which have lent their name to the documents of the papal chancery which they authenticate, popularly known as papal “bulls.” The earliest extant example of this series is of the year 746 (see Diplomatic). Leaden seals were also used by the archbishops of Ravenna and other prelates of Italy; also to some extent by officials of a lower rank, and by certain communes. The official seals of the doges of Venice and of Genoa and of other dignitaries of those states were also of lead. The sovereigns of Spain, too, made use of the same material; and in the Byzantine empire leaden bullae seem to have been universally employed, not only by emperors and state officials but also by private persons. Even in the north, metal bullae were also occasionally in use. Certain Carolingian monarchs, probably copying the practice of the papal chancery, issued diplomas authenticated by leaden seals, examples of the reign of Charles the Bald being still extant. The fashion even spread to Britain, as is proved by the existence in the British Museum of a leaden bulla of Cœnwulf of Mercia, A.D. 800–810. In Germany, too, bishops occasionally made use of leaden seals. But, while lead was the ordinary material for the metal seal, a more precious substance was occasionally used. On special occasions golden bullae were issued by the Byzantine emperors, by the popes, by the Carolings, although no actual examples of the last have survived, by the emperors of Germany, and by other sovereigns and rulers. Such specimens as have descended to us show that the golden bulla of the middle ages was usually hollow, being formed of two thin plates of metal stamped with the designs of obverse and reverse, soldered together at the edges and padded with wax or plaster. On rare occasions it was of solid gold. The popes attached golden bullae to their confirmations of the elections of the emperors in the 12th and 13th centuries; and they issued them on such occasions as when Leo X. conferred on Henry VIII. the title of Defender of the Faith, in 1521; on the coronation of Charles V., 1530; on the erection of the archbishopric of Lisbon into a patriarchate in 1716, &c.; and quite recently papal golden bullae have been conferred on royal personages. Comparatively few examples of golden bullae have survived. The value of the metal sufficiently accounts for their scarcity. Some examples are in the British Museum, viz. of Baldwin II. de Courtenay, formerly emperor of Constantinople, attached to a charter of 1269; of Edmund, king of Sicily, son of Henry III. of England; and of the emperor Frederick III., 1452–1493. In the Public Record Office, of Alfonso X. of Castile, ceding Gascony to Edward, son of Henry III. of England, 1254; of Clement VII. confirming to Henry VIII. the title of Defender of the Faith, 1524 (this example being the work of Benvenuto Cellini); and of Francis I. of France, ratifying the treaty with Henry VIII., 1527 (the counterpart with Henry’s bulla being in Paris).

Authorities.—W. de G. Birch, Catalogue of Seals in the British Museum (6 vols., 1887–1900); A. Wyon, The Great Seals of England (1887): G. Pedrick, Borough Seals of the Gothic Period (1904); H. Laing, Catalogue of Ancient Scottish Seals (1858, 1866); Douet d’Areq, Collection de sceaux (Inventaires el documents des archives de l’Empire) (3 vols., 1863–1868); G. Demay, Inoentaire des sceaux de la Flandre (2 vols., 1873), de l’Artois et de la Picardie (1877), de la Normandie (1881); G. Schlumberger, Sigillographie de l’empire byzantin (1884); J. von Pflugk-Hartun, Specimina selecta chartarum pontificum Romanarum (for papal bullae) (1885–1887); Catalogue of Engraved Gems in the Dept. of Greek and Roman Antiquities (British Museum, 1888); F. H. Marshall, Catalogue of the Finger-Rings, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman, in the British Museum (1907); E. Babelon, Histoire de la gravure sur gemmes en France (1902). There are also numerous papers on seals in Archaeologia and in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, and in the archaeological journals. Handbooks on diplomatic devote some attention to seals, e.g. A. Giry, Manuel de diplomatique (1894); H. Bresslau, Handbuch der Urkundenlehre für Deutschland und Italien (1889). (E. M. T.)