OKAPI, the native name of an African ruminant mammal (Ocapia johnstoni), belonging to the Giraffidae, or giraffe-family, but distinguished from giraffes by its shorter limbs and neck, the absence of horns in the females, and its very remarkable type of colouring. Its affinity with the giraffes is, however, clearly revealed by the structure of the skull and teeth, more especially the bilobed crown to the incisor-like lower canine teeth. At the shoulder the okapi stands about 5 ft. In colour the sides of the face are puce, and the neck and most of the body purplish, but the buttocks and upper part of both fore and hind limbs are transversely barred with black and white, while their lower portion is mainly white with black fetlock-rings, and in the front pair a vertical black stripe on the anterior surface. Males have a pair of dagger-shaped horns on the forehead, the tips of which, in some cases at any rate, perforate the hairy skin with which the rest of the horns are covered. As in all forest-dwelling animals, the ears are large and capacious. The tail is shorter than in giraffes, and not tufted at the tip. The okapi, of which the first entire skin sent to Europe was received in England from Sir H. H. Johnston in the spring of 1901, is a native of the Semliki forest, in the district between Lakes Albert and Albert Edward. From certain differences in the striping of the legs, as well as from variation in skull-characters, the existence of more than a single species has been suggested; but further evidence is required before such a view can be definitely accepted.

Specimens in the museum at Tervueren near Brussels show that in fully adult males the horns are subtriangular and inclined somewhat backwards; each being capped with a small polished epiphysis, which projects through the skin investing the rest of the horn. As regards its general characters, the skull of the okapi appears to be intermediate between that of the giraffe on the one hand and that of the extinct Palaeotragus (or Samotherium) of the Lower Pliocene deposits of southern Europe on the other. It has, for instance, a greater development of air-cells in the diplöe than in the latter, but much less than in the former. Again, in Palaeotragus the horns (present only in the male) are situated immediately over the eye-sockets, in Ocapia they are placed just behind the latter, while in Giraffa they are partly on the parietals. In general form, so far as can be judged from the disarticulated skeleton, the okapi was more like an antelope than a giraffe, the fore and hind cannon-bones, and consequently the entire limbs, being of approximately equal length. From this it seems probable that Palaeotragus and Ocapia indicate the ancestral type of the giraffe-line; while it has been further suggested that the apparently hornless Helladotherium of the Grecian Pliocene may occupy a somewhat similar position in regard to the horned Sivatherium of the Indian Siwaliks.

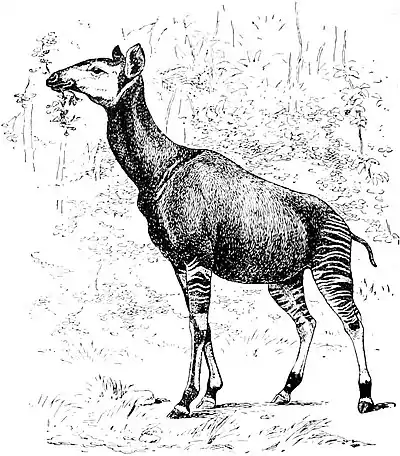

Female Okapi.

For these and other allied extinct genera see Pecora; for a full description of the okapi itself the reader should refer to an illustrated memoir by Sir E. Ray Lankester in the Transactions of the Zoological Society of London (xvi. 6, 1902), entitled “On Okapia, a New Genus of Giraffidae from Central Africa.”

Little is known with regard to the habits of the okapi. It appears, however, from the observations of Dr J. David, who spent some time in the Albert Edward district, that the creature dwells in the most dense parts of the primeval forest, where there is an undergrowth of solid-leaved, swamp-loving plants, such as arum, Donax and Phrynium, which, with orchids and climbing plants, form a thick and confused mass of vegetation. The leaves of these plants are blackish-green, and in the gloom of the forest, grow more or less horizontally, and are ghstening with moisture. The effect of the light falling upon them is to produce along the midrib of each a number of short white streaks of light, which contrast most strongly with the shadows cast by the leaves themselves, and with the general twilight gloom of the forest. On the other hand, the thick layer of fallen leaves on the ground, and the bulk of the stems of the forest trees are bluish-brown and russet, thus closely resembling the decaying leaves in an European forest after heavy rain; while the whole effect is precisely similar to that produced by the russet head and body and the striped thighs and limbs of the okapi. The long and mobile muzzle of the okapi appears to be adapted for feeding on the low forest underwood and the swamp-vegetation. The small size of the horns of the males is probably also an adaptation to life in thick underwood. In Dr David's opinion an okapi in its native forest could not be seen at a distance of more than twenty or twenty-five paces. At distances greater than this it is impossible to see anything clearly in these equatorial forests, and it is very difficult to do so even at this short distance. This suggests that the colouring of the okapi is of purely protective type.

By the Arabianized emancipated slaves of the Albert Edward district the okapi is known as the kenge, ó-à-pi being the Pigmies’ name for the creature. Dr David adds that Junker may undoubtedly claim to be the discoverer of the okapi, for, as stated on p. 299 of the third volume of the original German edition of his Travels, he saw in 1878 or 1879 in the Nepo district a portion of the skin with the characteristic black and white stripes. Junker, by whom it was mistaken for a large water-chevrotain or zebra-antelope, states that to the natives of the Nepo district the okapi is known as the makapé. (R. L.*)