GROUSE, a word of uncertain origin,[1] now used generally by ornithologists to include all the “rough-footed” Gallinaceous birds, but in common speech applied almost exclusively, when used alone, to the Tetrao scoticus of Linnaeus, the Lagopus scoticus of modern systematists—more particularly called in English the red grouse, but till the end of the 18th century almost invariably spoken of as the Moor-fowl or Moor-game. The effect which this species is supposed to have had on the British legislature, and therefore on history, is well known, for it was the common belief that parliament always rose when the season for grouse-shooting began (August 12th); while according to the Orkneyinga Saga (ed. Jonaeus, p. 356; ed. Anderson, p. 168) events of some importance in the annals of North Britain followed from its pursuit in Caithness in the year 1157.

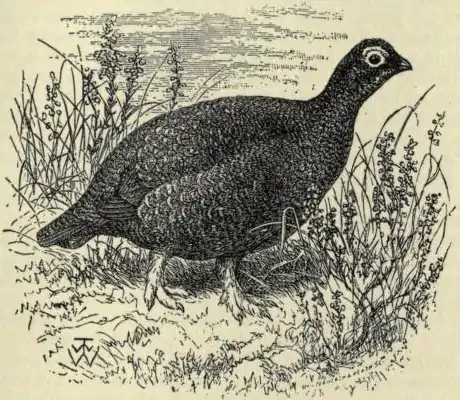

The red grouse is found on moors from Monmouthshire and Derbyshire northward to the Orkneys, as well as in most of the Hebrides. It inhabits similar situations throughout Wales and Ireland, but it does not naturally occur beyond the limits of the British Islands,[2] and is the only species among birds peculiar to them. The word “species” may in this case be used advisedly (since the red grouse invariably “breeds true,” it admits of an easy diagnosis, and it has a definite geographical range); but scarcely any zoologist can doubt of its common origin with the willow-grouse, Lagopus albus (L. subalpinus or L. saliceti of some authors), that inhabits a subarctic zone from Norway across the continents of Europe and Asia, as well as North America from the Aleutian Islands to Newfoundland. The red grouse indeed is rarely or never found away from the heather on which chiefly it subsists; while the willow-grouse in many parts of the Old World seems to prefer the shrubby growth of berry-bearing plants (Vaccinium and others) that, often thickly interspersed with willows and birches, clothes the higher levels or the lower mountain-slopes, and it flourishes in the New World where heather scarcely exists, and a “heath” in its strict sense is unknown. It is true that the willow-grouse always becomes white in winter, which the red grouse never does; but in summer there is a considerable resemblance between the two species, the cock willow-grouse having his head, neck and breast of nearly the same rich chestnut-brown as his British representative, and, though his back be lighter in colour, as is also the whole plumage of his mate, than is found in the red grouse, in other respects the two species are precisely alike. No distinction can be discovered in their voice, their eggs, their build, nor in their anatomical details, so far as these have been investigated and compared.[3] Moreover, the red grouse, restricted as is its range, varies in colour not inconsiderably according to locality.

|

| Red Grouse. |

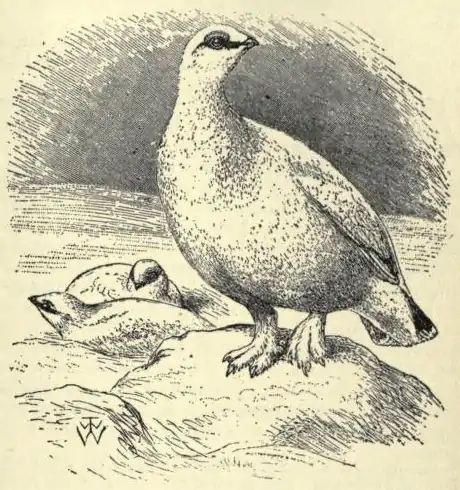

Though the red grouse does not, after the manner of other members of the genus Lagopus, become white in winter, Scotland possesses a species of the genus which does. This is the ptarmigan, L. mutus or L. alpinus, which differs far more in structure, station and habits from the red grouse than that does from the willow-grouse, and in Scotland is far less abundant, haunting only the highest and most barren mountains. It is said to have formerly inhabited both Wales and England, but there is no evidence of its appearance in Ireland. On the continent of Europe it is found most numerously in Norway, but at an elevation far above the growth of trees, and it occurs on the Pyrenees and on the Alps. It also inhabits northern Russia. In North America, Greenland and Iceland it is represented by a very nearly allied form—so much so indeed that it is only at certain seasons that the slight difference between them can be detected. This form is the L. rupestris of authors, and it would appear to be found also in Siberia (Ibis, 1879, p. 148). Spitzbergen is inhabited by a large form which has received recognition as L. hemileucurus, and the northern end of the chain of the Rocky Mountains is tenanted by a very distinct species, the smallest and perhaps the most beautiful of the genus, L. leucurus, which has all the feathers of the tail white.

|

| Ptarmigan. |

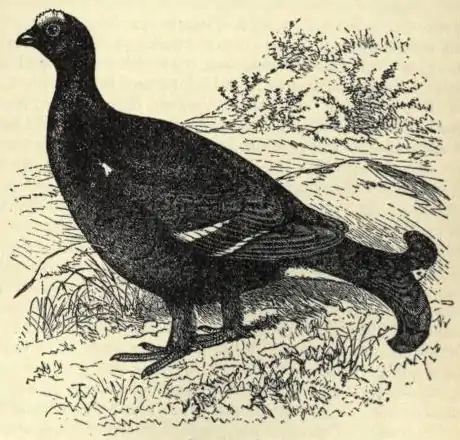

|

| Blackcock. |

The bird, however, to which the name of grouse in all strictness belongs is probably the Tetrao tetrix of Linnaeus—the blackcock and greyhen, as the sexes are respectively called. It is distributed over most of the heath-country of England, except in East Anglia, where attempts to introduce it have been only partially successful. It also occurs in North Wales and very generally throughout Scotland, though not in Orkney, Shetland or the Outer Hebrides, nor in Ireland. On the continent of Europe it has a very wide range, and it extends into Siberia. In Georgia its place is taken by a distinct species, on which a Polish naturalist (Proc. Zool. Society, 1875, p. 267) has conferred the name of T. mlokosiewiczi. Both these birds have much in common with their larger congener the capercally and its eastern representative.

The species of the genus Bonasa, of which the European B. sylvestris is the type, does not inhabit the British Islands. It is perhaps the most delicate game-bird that comes to table. It is the gelinotte of the French, the Haselhuhn of Germans, and Hjerpe of Scandinavians. Like its transatlantic congener B. umbellus, the ruffed grouse or birch-partridge (of which there are two other local forms, B. umbelloides and B. sabinii), it is purely a forest-bird. The same may be said of the species of Canace, of which two forms are found in America, C. canadensis, the spruce-partridge, and C. franklini, and also of the Siberian C. falcipennis. Nearly allied to these birds is the group known as Dendragapus, containing three large and fine forms D. obscurus, D. fuliginosus, and D. richardsoni—all peculiar to North America. Then there are Centrocercus urophasianus, the sage-cock of the plains of Columbia and California, and Pedioecetes, the sharp-tailed grouse, with its two forms, P. phasianellus and P. columbianus, while finally Cupidonia, the prairie-hen, also with two local forms, C. cupido and C. pallidicincta, is a bird that in the United States of America possesses considerable economic value, enormous numbers being consumed there, and also exported to Europe.

The various sorts of grouse are nearly all figured in Elliot’s Monograph of the Tetraoninae, and an excellent account of the American species is given in Baird, Brewer and Ridgway’s North American Birds (iii. 414-465). See also Shooting. (A. N.)

- ↑ It seems first to occur (O. Salusbury Brereton, Archaeologia, iii. 157) as “grows” in an ordinance for the regulation of the royal household dated “apud Eltham, mens. Jan. 22 Hen. VIII.,” i.e. 1531, and considering the locality must refer to black game. It is found in an Act of Parliament 1 Jac. I. cap. 27, § 2, i.e. 1603, and, as reprinted in the Statutes at Large, stands as now commonly spelt, but by many writers or printers the final e was omitted in the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1611 Cotgrave had “Poule griesche. A Moore-henne; the henne of the Grice [in ed. 1673 “Griece”] or Mooregame” (Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues, s.v. Poule). The most likely derivation seems to be from the old French word griesche, greoche or griais (meaning speckled, and cognate with griseus, grisly or grey), which was applied to some kind of partridge, or according to Brunetto Latini (Trés. p. 211) to a quail, “porce que ele fu premiers trovée en Grece.” The Oxford Dictionary repudiates the possibility of “grouse” being a spurious singular of an alleged plural “grice,” and, with regard to the possibility of “grows” being a plural of “grow,” refers to Giraldus Cambrensis (c. 1210), Topogr. Hib. opera (Rolls) v. 47: “gallinae campestres, quas vulgariter grutas vocant.”

- ↑ It was successfully, though with much trouble, introduced by Mr Oscar Dickson on a tract of land near Gottenburg in Sweden (Svenska Jägarförbundets Nya Tidskrift, 1868, p. 64 et alibi).

- ↑ A very interesting subject for discussion would be whether Lagopus scoticus or L. albus has varied most from the common stock of both. Looking to the fact that the former is the only species of the genus which does not assume white clothing in winter, an evolutionist might at first deem the variation greatest in its case; but then it must be borne in mind that the species of Lagopus which turn white differ in that respect from all other groups of the family Tetraonidae. Furthermore every species of Lagopus (even L. leucurus, the whitest of all) has its first set of remiges coloured brown. These are dropped when the bird is about half-grown, and in all the species but L. scoticus white remiges are then produced. If therefore the successive phases assumed by any animal in the course of its progress to maturity indicate the phases through which the species has passed, there may have been a time when all the species of Lagopus wore a brown livery even when adult, and the white dress donned in winter has been imposed upon the wearers by causes that can be easily suggested. The white plumage of the birds of this group protects them from danger during the snows of a protracted winter. But the red grouse, instead of perpetuating directly the more ancient properties of an original Lagopus that underwent no great seasonal change of plumage, may derive its ancestry from the widely-ranging willow-grouse, which in an epoch comparatively recent (in the geological sense) may have stocked Britain, and left descendants that, under conditions in which the assumption of a white garb would be almost fatal to the preservation of the species, have reverted (though doubtless with some modifications) to a comparative immutability essentially the same as that of the primal Lagopus.