DIAGRAM (Gr. διάγραμμα, from διαγράφειν, to mark out by lines), a figure drawn in such a manner that the geometrical relations between the parts of the figure illustrate relations between other objects. They may be classed according to the manner in which they are intended to be used, and also according to the kind of analogy which we recognize between the diagram and the thing represented. The diagrams in mathematical treatises are intended to help the reader to follow the mathematical reasoning. The construction of the figure is defined in words so that even if no figure were drawn the reader could draw one for himself. The diagram is a good one if those features which form the subject of the proposition are clearly represented.

Diagrams are also employed in an entirely different way—namely, for purposes of measurement. The plans and designs drawn by architects and engineers are used to determine the value of certain real magnitudes by measuring certain distances on the diagram. For such purposes it is essential that the drawing be as accurate as possible. We therefore class diagrams as diagrams of illustration, which merely suggest certain relations to the mind of the spectator, and diagrams drawn to scale, from which measurements are intended to be made. There are some diagrams or schemes, however, in which the form of the parts is of no importance, provided their connexions are properly shown. Of this kind are the diagrams of electrical connexions, and those belonging to that department of geometry which treats of the degrees of cyclosis, periphraxy, linkedness and knottedness.

Diagrams purely Graphic and mixed Symbolic and Graphic.—Diagrams may also be classed either as purely graphical diagrams, in which no symbols are employed except letters or other marks to distinguish particular points of the diagrams, and mixed diagrams, in which certain magnitudes are represented, not by the magnitudes of parts of the diagram, but by symbols, such as numbers written on the diagram. Thus in a map the height of places above the level of the sea is often indicated by marking the number of feet above the sea at the corresponding places on the map. There is another method in which a line called a contour line is drawn through all the places in the map whose height above the sea is a certain number of feet, and the number of feet is written at some point or points of this line. By the use of a series of contour lines, the height of a great number of places can be indicated on a map by means of a small number of written symbols. Still this method is not a purely graphical method, but a partly symbolical method of expressing the third dimension of objects on a diagram in two dimensions.

In order to express completely by a purely graphical method the relations of magnitudes involving more than two variables, we must use more than one diagram. Thus in the arts of construction we use plans and elevations and sections through different planes, to specify the form of objects having three dimensions. In such systems of diagrams we have to indicate that a point in one diagram corresponds to a point in another diagram. This is generally done by marking the corresponding points in the different diagrams with the same letter. If the diagrams are drawn on the same piece of paper we may indicate corresponding points by drawing a line from one to the other, taking care that this line of correspondence is so drawn that it cannot be mistaken for a real line in either diagram. (See Geometry: Descriptive.)

In the stereoscope the two diagrams, by the combined use of which the form of bodies in three dimensions is recognized, are projections of the bodies taken from two points so near each other that, by viewing the two diagrams simultaneously, one with each eye, we identify the corresponding points intuitively. The method in which we simultaneously contemplate two figures, and recognize a correspondence between certain points in the one figure and certain points in the other, is one of the most powerful and fertile methods hitherto known in science. Thus in pure geometry the theories of similar, reciprocal and inverse figures have led to many extensions of the science. It is sometimes spoken of as the method or principle of Duality. Geometry Projective.)

Diagrams in Mechanics

The study of the motion of a material system is much assisted by the use of a series of diagrams representing the configuration, displacement and acceleration of the parts of the system.

Diagram of Configuration.—In considering a material system it is often convenient to suppose that we have a record of its position at any given instant in the form of a diagram of configuration. The position of any particle of the system is defined by drawing a straight line or vector from the origin, or point of reference, to the given particle. The position of the particle with respect to the origin is determined by the magnitude and direction of this vector. If in the diagram we draw from the origin (which need not be the same point of space as the origin for the material system) a vector equal and parallel to the vector which determines the position of the particle, the end of this vector will indicate the position of the particle in the diagram of configuration. If this is done for all the particles we shall have a system of points in the diagram of configuration, each of which corresponds to a particle of the material system, and the relative positions of any pair of these points will be the same as the relative positions of the material particles which correspond to them.

We have hitherto spoken of two origins or points from which the vectors are supposed to be drawn—one for the material system, the other for the diagram. These points, however, and the vectors drawn from them, may now be omitted, so that we have on the one hand the material system and on the other a set of points, each point corresponding to a particle of the system, and the whole representing the configuration of the system at a given instant.

This is called a diagram of configuration.

Diagram of Displacement.—Let us next consider two diagrams of configuration of the same system, corresponding to two different instants. We call the first the initial configuration and the second the final configuration, and the passage from the one configuration to the other we call the displacement of the system. We do not at present consider the length of time during which the displacement was effected, nor the intermediate stages through which it passed, but only the final result—a change of configuration. To study this change we construct a diagram of displacement.

Let A, B, C be the points in the initial diagram of configuration, and A′, B′, C′ be the corresponding points in the final diagram of configuration. From o, the origin of the diagram of displacement, draw a vector oa equal and parallel to AA′, ob equal and parallel to BB′, oc to CC′, and so on. The points a, b, c, &c., will be such that the vector ab indicates the displacement of B relative to A, and so on. The diagram containing the points a, b, c, &c., is therefore called the diagram of displacement.

In constructing the diagram of displacement we have hitherto assumed that we know the absolute displacements of the points of the system. For we are required to draw a line equal and parallel to AA′, which we cannot do unless we know the absolute final position of A, with respect to its initial position. In this diagram of displacement there is therefore, besides the points a, b, c, &c., an origin, o, which represents a point absolutely fixed in space. This is necessary because the two configurations do not exist at the same time; and therefore to express their relative position we require to know a point which remains the same at the beginning and end of the time.

But we may construct the diagram in another way which does not assume a knowledge of absolute displacement or of a point fixed in space. Assuming any point and calling it a, draw ak parallel and equal to BA in the initial configuration, and from k draw kb parallel and equal to A′B′ in the final configuration. It is easy to see that the position of the point b relative to a will be the same by this construction as by the former construction, only we must observe that in this second construction we use only vectors such as AB, A′B′, which represent the relative position of points both of which exist simultaneously, instead of vectors such as AA′, BB′, which express the position of a point at one instant relative to its position at a former instant, and which therefore cannot be determined by observation, because the two ends of the vector do not exist simultaneously.

It appears therefore that the diagram of displacements, when drawn by the first construction, includes an origin o, which indicates that we have assumed a knowledge of absolute displacements. But no such point occurs in the second construction, because we use such vectors only as we can actually observe. Hence the diagram of displacements without an origin represents neither more nor less than all we can ever know about the displacement of the material system.

Diagram of Velocity.—If the relative velocities of the points of the system are constant, then the diagram of displacement corresponding to an interval of a unit of time between the initial and the final configuration is called a diagram of relative velocity. If the relative velocities are not constant, we suppose another system in which the velocities are equal to the velocities of the given system at the given instant and continue constant for a unit of time. The diagram of displacements for this imaginary system is the required diagram of relative velocities of the actual system at the given instant. It is easy to see that the diagram gives the velocity of any one point relative to any other, but cannot give the absolute velocity of any of them.

Diagram of Acceleration.—By the same process by which we formed the diagram of displacements from the two diagrams of initial and final configuration, we may form a diagram of changes of relative velocity from the two diagrams of initial and final velocities. This diagram may be called that of total accelerations in a finite interval of time. And by the same process by which we deduced the diagram of velocities from that of displacements we may deduce the diagram of rates of acceleration from that of total acceleration.

We have mentioned this system of diagrams in elementary kinematics because they are found to be of use especially when we have to deal with material systems containing a great number of parts, as in the kinetic theory of gases. The diagram of configuration then appears as a region of space swarming with points representing molecules, and the only way in which we can investigate it is by considering the number of such points in unit of volume in different parts of that region, and calling this the density of the gas.

In like manner the diagram of velocities appears as a region containing points equal in number but distributed in a different manner, and the number of points in any given portion of the region expresses the number of molecules whose velocities lie within given limits. We may speak of this as the velocity-density.

Diagrams of Stress.—Graphical methods are peculiarly applicable to statical questions, because the state of the system is constant, so that we do not need to construct a series of diagrams corresponding to the successive states of the system. The most useful of these applications, collectively termed Graphic Statics, relates to the equilibrium of plane framed structures familiarly represented in bridges and roof-trusses. Two diagrams are used, one called the diagram of the frame and the other called the diagram of stress. The structure itself consists of a number of separable pieces or links jointed together at their extremities. In practice these joints have friction, or may be made purposely stiff, so that the force acting at the extremity of a piece may not pass exactly through the axis of the joint; but as it is unsafe to make the stability of the structure depend in any degree upon the stiffness of joints, we assume in our calculations that all the joints are perfectly smooth, and therefore that the force acting on the end of any link passes through the axis of the joint.

The axes of the joints of the structure are represented by points in the diagram of the frame. The link which connects two joints in the actual structure may be of any shape, but in the diagram of the frame it is represented by a straight line joining the points representing the two joints. If no force acts on the link except the two forces acting through the centres of the joints, these two forces must be equal and opposite, and their direction must coincide with the straight line joining the centres of the joints. If the force acting on either extremity of the link is directed towards the other extremity, the stress on the link is called pressure and the link is called a "strut." If it is directed away from the other extremity, the stress on the link is called tension and the link is called a "tie." In this case, therefore, the only stress acting in a link is a pressure or a tension in the direction of the straight line which represents it in the diagram of the frame, and all that we have to do is to find the magnitude of this stress. In the actual structure gravity acts on every part of the link, but in the diagram we substitute for the actual weight of the different parts of the link two weights which have the same resultant acting at the extremities of the link.

We may now treat the diagram of the frame as composed of links without weight, but loaded at each joint with a weight made up of portions of the weights of all the links which meet in that joint. If any link has more than two joints we may substitute for it in the diagram an imaginary stiff frame, consisting of links, each of which has only two joints. The diagram of the frame is now reduced to a system of points, certain pairs of which are joined by straight lines, and each point is in general acted on by a weight or other force acting between it and some point external to the system. To complete the diagram we may represent these external forces as links, that is to say, straight lines joining the points of the frame to points external to the frame. Thus each weight may be represented by a link joining the point of application of the weight with the centre of the earth.

But we can always construct an imaginary frame having its joints in the lines of action of these external forces, and this frame, together with the real frame and the links representing external forces, which join points in the one frame to points in the other frame, make up together a complete self-strained system in equilibrium, consisting of points connected by links acting by pressure or tension. We may in this way reduce any real structure to the case of a system of points with attractive or repulsive forces acting between certain pairs of these points, and keeping them in equilibrium. The direction of each of these forces is sufficiently indicated by that of the line joining the points, so that we have only to determine its magnitude. We might do this by calculation, and then write down on each link the pressure or the tension which acts in it.

We should in this way obtain a mixed diagram in which the stresses are represented graphically as regards direction and position, but symbolically as regards magnitude. But we know that a force may be represented in a purely graphical manner by a straight line in the direction of the force containing as many units of length as there are units of force in the force. The end of this line is marked with an arrow head to show in which direction the force acts. According to this method each force is drawn in its proper position in the diagram of configuration of the frame. Such a diagram might be useful as a record of the result of calculation of the magnitude of the forces, but it would be of no use in enabling us to test the correctness of the calculation.

But we have a graphical method of testing the equilibrium of any set of forces acting at a point. We draw in series a set of lines parallel and proportional to these forces. If these lines form a closed polygon the forces are in equilibrium. (See Mechanics.) We might in this way form a series of polygons of forces, one for each joint of the frame. But in so doing we give up the principle of drawing the line representing a force from the point of application of the force, for all the sides of the polygon cannot pass through the same point, as the forces do. We also represent every stress twice over, for it appears as a side of both the polygons corresponding to the two joints between which it acts. But if we can arrange the polygons in such a way that the sides of any two polygons which represent the same stress coincide with each other, we may form a diagram in which every stress is represented in direction and magnitude, though not in position, by a single line which is the common boundary of the two polygons which represent the joints at the extremities of the corresponding piece of the frame.

We have thus obtained a pure diagram of stress in which no attempt is made to represent the configuration of the material system, and in which every force is not only represented in direction and magnitude by a straight line, but the equilibrium of the forces at any joint is manifest by inspection, for we have only to examine whether the corresponding polygon is closed or not.

The relations between the diagram of the frame and the diagram of stress are as follows:—To every link in the frame corresponds a straight line in the diagram of stress which represents in magnitude and direction the stress acting in that link; and to every joint of the frame corresponds a closed polygon in the diagram, and the forces acting at that joint are represented by the sides of the polygon taken in a certain cyclical order, the cyclical order of the sides of the two adjacent polygons being such that their common side is traced in opposite directions in going round the two polygons.

The direction in which any side of a polygon is traced is the direction of the force acting on that joint of the frame which corresponds to the polygon, and due to that link of the frame which corresponds to the side. This determines whether the stress of the link is a pressure or a tension. If we know whether the stress of any one link is a pressure or a tension, this determines the cyclical order of the sides of the two polygons corresponding to the ends of the links, and therefore the cyclical order of all the polygons, and the nature of the stress in every link of the frame.

Reciprocal Diagrams.—When to every point of concourse of the lines in the diagram of stress corresponds a closed polygon in the skeleton of the frame, the two diagrams are said to be reciprocal.

The first extensions of the method of diagrams of forces to other cases than that of the funicular polygon were given by Rankine in his Applied Mechanics (1857). The method was independently applied to a large number of cases by W. P. Taylor, a practical draughtsman in the office of J. B. Cochrane, and by Professor Clerk Maxwell in his lectures in King’s College, London. In the Phil. Mag. for 1864 the latter pointed out the reciprocal properties of the two diagrams, and in a paper on “Reciprocal Figures, Frames and Diagrams of Forces,” Trans. R.S. Edin. vol. xxvi., 1870, he showed the relation of the method to Airy’s function of stress and to other mathematical methods. Professor Fleeming Jenkin has given a number of applications of the method to practice (Trans. R.S. Edin. vol. xxv.).

L. Cremona (Le Figure reciproche nella statica grafica, 1872) deduced the construction of reciprocal figures from the theory of the two components of a wrench as developed by Möbius. Karl Culmann, in his Graphische Statik (1st ed. 1864–1866, 2nd ed. 1875), made great use of diagrams of forces, some of which, however, are not reciprocal. Maurice Levy in his Statique graphique (1874) has treated the whole subject in an elementary but copious manner, and R. H. Bow, in his The Economics of Construction in Relation to Framed Structures (1873), materially simplified the process of drawing a diagram of stress reciprocal to a given frame acted on by a system of equilibrating external forces.

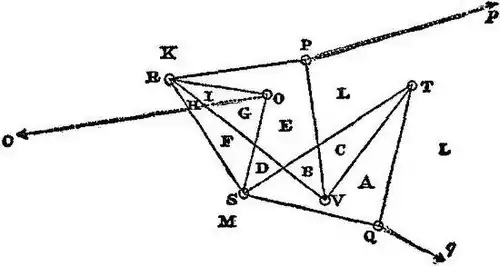

Fig. 1 Diagram of Configuration.

Instead of lettering the joints of the frame, as is usually done, or the links of the frame, as was the custom of Clerk Maxwell, Bow places a letter in each of the polygonal areas enclosed by the links of the frame, and also in each of the divisions of surrounding space as separated by the lines of action of the external forces. When one link of the frame crosses another, the point of apparent intersection of the links is treated as if it were a real joint, and the stresses of each of the intersecting links are represented twice in the diagram of stress, as the opposite sides of the parallelogram which corresponds to the point of intersection.

This method is followed in the lettering of the diagram of configuration (fig. 1), and the diagram of stress (fig. 2) of the linkwork which Professor Sylvester has called a quadruplane.

In fig. 1 the real joints are distinguished from the places where one link appears to cross another by the little circles O, P, Q, R, S, T, V. The four links RSTV form a “contraparallelogram” in which RS = TV and RV = ST. The triangles ROS, RPV, TQS are similar to each other. A fourth triangle (TNV), not drawn in the figure, would complete the quadruplane. The four points O, P, N, Q form a parallelogram whose angle POQ is constant and equal to π — SOR. The product of the distances OP and OQ is constant. The linkwork may be fixed at O. If any figure is traced by P, Q will trace the inverse figure, but turned round O through the constant angle POQ. In the diagram forces Pp, Qq are balanced by the force Co at the fixed point. The forces Pp and Qq are necessarily inversely as OP and OQ, and make equal angles with those lines.

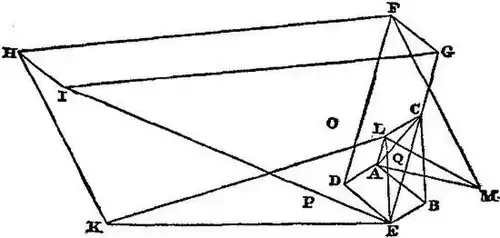

Fig. 2 Diagram of Stress.

Every closed area formed by the links or the external forces in the diagram of configuration is marked by a letter which corresponds to a point of concourse of lines in the diagram of stress. The stress in the link which is the common boundary of two areas is represented in the diagram of stress by the line joining the points corresponding to those areas. When a link is divided into two or more parts by lines crossing it, the stress in each part is represented by a different line for each part, but as the stress is the same throughout the link these lines are all equal and parallel. Thus in the figure the stress in RV is represented by the four equal and parallel lines HI, FG, DE and AB. If two areas have no part of their boundary in common the letters corresponding to them in the diagram of stress are not joined by a straight line. If, however, a straight line were drawn between them, it would represent in direction and magnitude the resultant of all the stresses in the links which are cut by any line, straight or curved, joining the two areas. For instance the areas F and C in fig. 1 have no common boundary, and the points F and C in fig. 2 are not joined by a straight line. But every path from the area F to the area C in fig. 1 passes through a series of other areas, and each passage from one area into a contiguous area corresponds to a line drawn in the diagram of stress. Hence the whole path from F to C in fig. 1 corresponds to a path formed of lines in fig. 2 and extending from F to C, and the resultant of all the stresses in the links cut by the path is represented by FC in fig. 2.

Many examples of stress diagrams are given in the article on bridges (q.v.).

Automatic Description of Diagrams.

There are many other kinds of diagrams in which the two co-ordinates of a point in a plane are employed to indicate the simultaneous values of two related quantities. If a sheet of paper is made to move, say horizontally, with a constant known velocity, while a tracing point is made to move in a vertical straight line, the height varying as the value of any given physical quantity, the point will trace out a curve on the paper from which the value of that quantity at any given time may be determined. This principle is applied to the automatic registration of phenomena of all kinds, from those of meteorology and terrestrial magnetism to the velocity of cannon-shot, the vibrations of sounding bodies, the motions of animals, voluntary and involuntary, and the currents in electric telegraphs.

In Watt’s indicator for steam engines the paper does not move with a constant velocity, but its displacement is proportional to that of the piston of the engine, while that of the tracing point is proportional to the pressure of the steam. Hence the co-ordinates of a point of the curve traced on the diagram represent the volume and the pressure of the steam in the cylinder. The indicator-diagram not only supplies a record of the pressure of the steam at each stage of the stroke of the engine, but indicates the work done by the steam in each stroke by the area enclosed by the curve traced on the diagram. (J. C. M.)