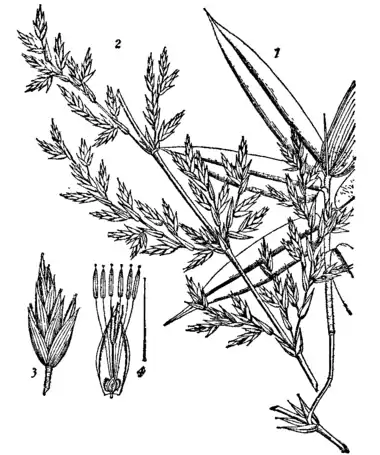

BAMBOO, the popular name for a tribe of grasses, Bambuseae, which are large, often tree-like, with woody stems. The stems spring from an underground root-stock and are often crowded to form dense clumps; the largest species reach 120 ft. in height. The slender stem is hollow, and, as generally in grasses, has well-marked joints or nodes, at which the cavity is closed by a strong diaphragm. The branches are numerous and in some species spiny; the narrow, often short, leaf-blade is usually jointed at the base and has a short stalk, by which it is attached to the long sheath. The spikelets are usually many-flowered and variously arranged in racemes or panicles. The flower differs from that of the majority of grasses in having usually three lodicules and six stamens. Many species bloom annually, but others only at intervals sometimes of many years, when the individuals of one and the same species are found in bloom over large areas. Thus on the west coast of India the simultaneous blooming of Bambusa arundinacea (fig. 1), one of the largest species, has been observed at intervals of thirty-two years. After ripening of the seed, the leafless flowering culms always die down.

|

| Fig. 1.—Bambusa arundinacea, an Indian bamboo. 1, Leafy shoot. 2, Branch of inflorescence. 3, Spikelet. 4, Flower. |

The Bambuseae contain twenty-three genera and occur throughout the tropical zone, but very unevenly distributed; they also extend into the sub-tropical and even into the temperate zone. Tropical Asia is richest in species; in Africa there are very few. In Asia they extend into Japan and to 10,000 ft. or more on the Himalayas; and in the Andes of South America they reach the snow-line.

The fruit in Bambusa, Arundinaria and other genera resembles the grain generally characteristic of grasses, but in Dendrocalamus and others it is a nut, while rarely, as in Melocanna, it is fleshy and suggests an apple in size and appearance. The uses to which all the parts and products of the bamboo are applied in Oriental countries are almost endless. The soft and succulent shoots, when just beginning to spring, are cut off and served up at table like asparagus. Like that vegetable, also, they are earthed over to keep them longer fit for consumption; and they afford a continuous supply during the whole year, though it is more abundant in autumn. They are also salted and eaten with rice, prepared in the form of pickles or candied and preserved in sugar. As the plant grows older, a species of fluid is secreted in the hollow joints, in which a concrete substance once highly valued in the East for its medicinal qualities, called tabaxir or tabascheer, is gradually developed. This substance, which has been found to be a purely siliceous concretion, is possessed of peculiar optical properties. As a medicinal agent the bamboo is entirely inert, and it has never been received into the European materia medica.

|

| Fig. 2.—Bamboo (Bambusa vulgaris), very much reduced. Grows 20 to 50 ft high. |

The grains of the bamboo are available for food, and the Chinese have a proverb that it produces seed more abundantly in years when the rice crop fails, which means, probably, that in times of dearth the natives look more after such a source of food. The Hindus eat it mixed with honey as a delicacy, equal quantities being put into a hollow joint, coated externally with clay, and thus roasted over a fire. The fleshly fruit of Melocanna is baked and eaten. The plant is a native of India, but is sometimes cultivated as in Mauritius. It is, however, the stem of the bamboo which is applied to the greatest variety of uses. Joints of sufficient size form water buckets; smaller ones are used as bottles, and among the Dyaks of Borneo they are employed as cooking vessels. Bamboo is extensively used as a timber wood, and houses are frequently made entirely out of the products of the plant; complete sections of the stem form posts or columns; split up, it serves for floors or rafters; and, interwoven in lattice-work, it is employed for the sides of rooms, admitting light and air. The roof is sometimes of bamboo solely, and when split, which is accomplished with the greatest ease, it can be formed into laths or planks. It is employed in shipping of all kinds; some of the strongest plants are selected for masts of boats of moderate size, and the masts of larger vessels are sometimes formed by the union of several bamboos built up and joined together.

The bamboo is employed in the construction of all kinds of agricultural and domestic implements and in the materials and implements required in fishery. Bows are made of it by the union of two pieces with many bands; and, the septa being bored out and the lengths joined together, it is employed, as we use leaden pipes, in transmitting water to reservoirs or gardens. From the light and slender stalks shafts for arrows are obtained; and in the south-west of Asia there is a certain species of equally slender growth, from which writing-pens or reeds are made. A joint forms a holder for papers or pens, and it was in a joint of bamboo that silk-worm eggs were carried from China to Constantinople during the reign of Justinian. The outer cuticle of Oriental species is so hard that it forms a sharp and durable cutting edge, and it is so siliceous that it can be used as a whetstone. This outer cuticle, cut into thin strips, is one of the most durable and beautiful materials for basket-making, and both in China and Japan it is largely so employed. Strips are also woven into cages, chairs, beds and other articles of furniture, Oriental wicker-work in bamboo being unequalled for beauty and neatness of workmanship. In China the interior portions of the stem are beaten into a pulp and used for the manufacture of the finer varieties of paper. Bamboos are imported to a considerable extent into Europe for the use of basket-makers, and for umbrella and walking-sticks. In short, the purposes to which the bamboo is applicable are almost endless, and well justify the opinion that “it is one of the most wonderful and most beautiful productions of the tropics, and one of Nature’s most valuable gifts to uncivilized man” (A. R. Wallace, The Malay Archipelago).

A number of species of bamboo are hardy under cultivation in the British Isles. A useful and interesting account of these and their cultivation will be found in the Bamboo Garden, by A. B. Freeman-Mitford. They are mostly natives of China and Japan and belong to the genera Arundinaria, Bambusa and Phyllostachys; but include a few Himalayan species of Arundinaria. They may be propagated by seed (though owing to the rare occurrence of fruit, this method is seldom applicable), by division and by cuttings. They are described as hungry plants which well repay generous treatment, and will flourish in a rich, not too stiff loam, and for the first year or two should be well mulched. They should be sheltered from winds and well watered during the growing period. When being transplanted the roots must be disturbed as little as possible. The following may be mentioned; Arundinaria simoni, a fine plant which in the bamboo garden at Kew has reached 18 ft. in height, and not infrequently flowers and fruits in Britain; A. japonica, a tall and handsome plant generally grown in gardens under the name Bambusa métaké; A. nitida, “by far the daintiest and most attractive of all its genus, and remarkably hardy”; Bambusa palmata, with leaves a foot or more long and three inches broad; B. tesselata; B. quadrangularis, remarkable for its square stems; Phyllostachys mitis, growing to 60 ft. high in its native home, China and Japan; and P. nigra, so called from the black stem, a handsome species.