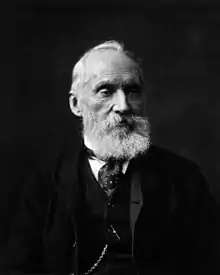

William Thomson

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin, OM, GCVO, PC, FRS, FRSE (26 June 1824 – 17 December 1907) was a Scots-Irish[2][5] mathematical physicist and engineer. He was born in Belfast in 1824. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formed the first and second laws of thermodynamics.

The Lord Kelvin | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Royal Society | |

| In office 1890–1895 | |

| Preceded by | George Stokes |

| Succeeded by | Lord Lister |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 26 June 1824 Belfast, Ireland |

| Died | 17 December 1907 (aged 83) Largs, Ayrshire, Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Scots-Irish[1][2] |

| Spouse(s) | Margaret Crum (m. 1852; died 1870) Frances Blandy [3](m. 1874–1907) |

| Children | none[4] |

| Residence | Belfast; Glasgow; Cambridge |

| Signature | |

| Alma mater |

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | University of Glasgow |

| Academic advisors | William Hopkins |

| Notable students |

|

| Influences |

|

| Influenced | Andrew Gray |

| It is believed the "PNP" in his signature stands for "Professor of Natural Philosophy". Kelvin also wrote under the pseudonym "P. Q. R." | |

Works

Kelvin did much to unify physics in its modern form. He also had a career as an electric telegraph engineer and inventor, which propelled him into the public eye and gave him wealth, fame and honour.

For his work on the transatlantic telegraph project he was knighted in 1866 by Queen Victoria, becoming Sir William Thomson. He was noted for his work on the mariner's compass. This had been rather unreliable owing to the iron in ships' hulls.

Absolute temperatures are stated in units of kelvin in his honour. The existence of a lower limit to temperature (absolute zero) was known before his work, but Lord Kelvin found its correct value as approximately −273.15 degree Celsius or −459.67 degree Fahrenheit.

He was made Lord Kelvin in 1892 in recognition of his achievements in thermodynamics, and of his opposition to Irish Home Rule.[6][7][8] He became Baron Kelvin, of Largs in the County of Ayr.

He was the first British scientist to be elevated to the House of Lords. His title refers to the River Kelvin, which flows close by his laboratory at the University of Glasgow. Despite offers from several world-renowned universities, Lord Kelvin refused to leave Glasgow, remaining Professor of Natural Philosophy for over 50 years, until his eventual retirement. The Hunterian Museum at the University of Glasgow has a permanent exhibition on the work of Lord Kelvin.

Always active in industrial research and development, he was recruited around 1899 by George Eastman to serve as vice-chairman of the board of the British company Kodak Limited, affiliated with Eastman Kodak.[9]

References

- Grabiner, Judy (2002). "Creators of Mathematics: The Irish Connection (book review)" (PDF). Irish Math. Soc. Bulletin. 48: 67. doi:10.33232/BIMS.0048.65.68. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- "Significant Scots. William Thomson (Lord Kelvin)". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- "William Thomson, Lord Kelvin. Scientist, Mathematician and Engineer". Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

His first wife was Margaret Crum and he married secondly Frances Blandy but had no children.

- Grabiner, Judy (2002). "Creators of Mathematics: The Irish Connection (book review)" (PDF). Irish Math. Soc. Bulletin. 48: 67. doi:10.33232/BIMS.0048.65.68. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Kelvin and Ireland Raymond Flood, Mark McCartney and Andrew Whitaker (2009) J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 158 011001

- Randall, Lisa (2005). Warped Passages. New York: HarperCollins. p.162

- "Hutchison, Iain "Lord Kelvin and Liberal Unionism"" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- Lord Kelvin, Recipient of The John Fritz Medal in 1905 Matthew Trainer, Physics in Perspective, (2008) 10, 212-223