Tay Bridge

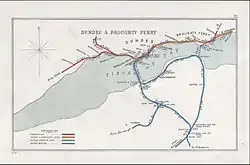

The Tay Bridge (or Tay Rail Bridge) is a railway bridge about 2.25 miles (3.62 kilometres) long[1] that spans the Firth of Tay in Scotland, between the city of Dundee and Wormit, Fife (grid reference NO391277).

Tay Bridge | |

|---|---|

Tay Bridge at Dundee, Scotland from the Dundee Law | |

| Coordinates | 56°26′14.4″N 2°59′18.4″W |

| Carries | Rail traffic |

| Crosses | Firth of Tay |

| Locale | Dundee to Wormit, Scotland |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 3,264 metres (10,709 ft) |

| History | |

| Construction start | 22 July 1871 (1st) 6 July 1883 (2nd) |

| Construction end | early 1878 (1st) 1887 (2nd) |

| Opened | 1 June 1878 (1st) 20 June 1887 (2nd) |

| Closed | 28 December 1879 (1st) |

| Location | |

As with the Forth Rail Bridge, the Tay Bridge has been called the Tay Rail Bridge since the construction of the Tay Road Bridge over the firth. The original rail bridge replaced an early train ferry.

The present Tay Bridge is the second Rail bridge over the Tay. The first one collapsed in 1879 in a storm, with great loss of life.

First rail bridge

The original Tay Bridge was designed by noted railway engineer Thomas Bouch,[2] who received a knighthood when the bridge was completed.[3] It was a lattice-grid design, combining cast and wrought iron. The design was well known: it was used with success in the Crumlin Viaduct in South Wales in 1858, after the use of cast iron in the Crystal Palace.

A previous cast iron design, the Dee bridge which collapsed in 1847, failed due to poor use of cast-iron girders. Later, Gustave Eiffel used a similar design to create several large viaducts in the Massif Central (1867).

Proposals for constructing a bridge across the River Tay date back to at least 1854. The North British Railway (Tay Bridge) Act received the Royal Assent on 15 July 1870 and the foundation stone was laid on 22 July 1871.

The bridge design: the basic idea

The original design was for lattice girders supported by brick piers resting on bedrock shown by trial borings to lie at no great depth under the river. At either end of the bridge the single rail track ran on top of the bridge girder, most of which therefore lay below the pier tops. However, in the centre section of the bridge (the “high girders”) the railway ran inside the bridge girder, which could then run above the pier tops to give the required clearance to allow passage of sailing ships upriver (e.g. to Perth).

However as the bridge extended out into the river, it became clear in December 1873,[4] that the bedrock really lay much deeper; too deep to act as a foundation for the bridge piers. Bouch had to redesign the bridge.

He reduced the number of piers and increased the span of the girders. The pier foundations were no longer taken down to bedrock; instead they were constructed by sinking brick-lined wrought-iron caissons onto the riverbed,[5][6]

The work

The company which had the contract for building the bridge went bankrupt while Bouch was redesigning the bridge. The replacement company did poor work. Almost every part of the bridge was substandard, including the iron and the ties and fixings.[7] Lack of precision in the bolts and braces led to ad hoc on-site fixes, described by one witness at the later inquiry as "about as slovenly a piece of work as ever I saw in my life".[8]

Opening

The bridge was opened for passenger traffic on 1 June 1878.[9] The next year, on June 20 1879, Queen Victoria crossed the bridge to return south from Balmoral. Bouch was presented to her before she did so, and on June 26th 1879 he was knighted by the Queen at Windsor Castle.

The Tay Bridge Disaster

On the night of 28 December 1879 at 7.15pm, the bridge collapsed after its central spans gave way during high winter gales. A train with six carriages carrying seventy-five passengers and crew, crossing at the time of the collapse, plunged into the icy waters of the Tay. All seventy-five were lost. The disaster stunned the whole country and sent shock waves through the Victorian engineering community.[10]

At the time a gale estimated at force ten or eleven (Tropical Storm force winds: 55–72 mph/80–117 km/hr) had been blowing down the Tay estuary at right angles to the bridge. The engine itself was salvaged from the river and restored to the railways for service.

The collapse of the bridge, opened only nineteen months earlier and passed as safe by the Board of Trade, is still the most famous bridge disaster in the British Isles.[10] The stumps of the original bridge piers are still visible above the surface of the Tay even at high tide.

Causes

The inquiry held that the fall of the bridge was occasioned by the insufficiency of the cross-bracings and fastenings to sustain the force of the gale on the night of December 28th 1879 and that the bridge had been previously strained by other gales.

However, this is not a finding that the bridge as designed would have failed. The engineer appointed to carry out detailed investigations testified:

- "Wind-pressure alone (supposing the structure to have been perfectly made, and so designed) to the amount of 37 lbs to the square foot would have overthrown it, but that, being perfect, it fell in consequence of an excess of wind-pressure is evidently not the case, [because] it did not fall upon those points which would have been the least lines of resistance had the structure been perfect. The mode in which it fell shows that there must have been weak points in the structure and that, with the knowledge which I have [of parts which already had to be repaired], ... shows me that the structure was not in that perfect condition".[11]

The section in the middle of the bridge, where the rail ran inside high girders, was potentially top-heavy and very vulnerable to high winds. Neither Bouch nor the contractor appeared to have regularly visited the on-site foundry where iron from the previous half-built bridge was recycled. The cylindrical cast iron columns supporting the 13 longest spans of the bridge, each 245 ft (75 m) long, were of poor quality. Many had been cast horizontally, with the result that the walls were not of even thickness, and there was some evidence that imperfect castings were disguised from the (very inadequate) quality control inspections.

In particular, some of the lugs used as attachment points for the wrought iron bracing bars had been "burnt on" rather than cast with the columns. Even the normal lugs were very weak. They were tested for the Inquiry, and proved to break at only about 20 long tons (20 t) rather than the expected load of 60 long tons (61 t). These lugs failed and destabilised the entire centre of the bridge during the storm.

Put into simple words, the bridge failed because of defects in its manufacture. This meant it did not reach the standards of wind resistance intended by the designer.

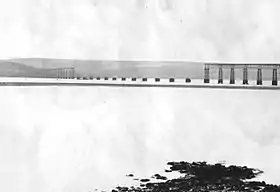

The second bridge

A new double-track bridge was designed by William Henry Barlow. It was built by William Arrol & Co. 18 metres (59 ft) upstream of, and parallel to, the original bridge. The foundation stone laid on 6 July 1883. Construction involved 25,000 metric tons (28,000 short tons) of iron and steel, 70,000 metric tons (77,000 short tons) of concrete, ten million bricks (weighing 37,500 metric tons (41,300 short tons)) and three million rivets. Fourteen men lost their lives during its construction, most by drowning.

The second bridge opened on 13 July 1887 and is still in use. In 2003, a £20.85 million strengthening and refurbishment project (£NaN as of 2024),[12] on the bridge was completed. More than 1,000 metric tons (1,100 short tons) of bird droppings were scraped off the ironwork lattice of the bridge using hand tools, and bagged into 25 kilograms (55 lb) sacks. Hundreds of thousands of rivets were removed and replaced. All work was done in very exposed conditions high over fast-running tides in the river.

References

- Including a brick viaduct

- Rapley, John 2006. Thomas Bouch : the builder of the Tay Bridge. Stroud : Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3695-3

- Firth of Tay Bridge (1877) at Structurae

- Minutes of Evidence p 402 – evidence of Sir T Bouch

- A caisson is a watertight structure under water. At first it is hollow, then filled with concrete. Its function is to support the weight of a bridge or other structure.

- The Tay Bridge by A. Grothe C.E. Manager of the Tay Bridge contract. Good Words (1878)

- Report of the Court of Inquiry, paragraph 11.

- Minutes of Evidence - evidence of H Law page 331

- Thomas, John (1969). The North British Railway, vol. 1. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4697-0.

- Thomas, John 1972. The Tay Bridge disaster: new light on the 1879 tragedy. David & Charles, London. ISBN 0-7153-5198-2

- Evidence of Henry Law, pp. 307-308 Minutes of Evidence

- UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Measuring Worth: UK CPI.