Stream cipher

In cryptography, a stream cipher is a symmetric key cipher where plaintext bits are combined with a pseudorandom cipher bit stream (keystream) using an exclusive-or (xor) operation. In a stream cipher the Plaintext digits are encrypted one at a time, and the transformation of successive digits varies during the encryption state. An alternative name is a state cipher, as the encryption of each digit is dependent on the current state. In practice, the digits are typically single bits or bytes.

Stream ciphers represent a different approach to symmetric encryption from block ciphers. Block ciphers operate on large blocks of fixed length. Stream ciphers typically execute at a higher speed than block ciphers and have lower hardware requirements. However, stream ciphers can have serious security problems if used incorrectly; in particular, the same starting state must never be used twice.

A stream cipher makes use of a much smaller and more convenient cryptographic key, for example 128 bits keys. Based on this key, it generates a pseudorandom keystream which can be combined with the plaintext digits in a similar way to the one-time pad encryption algorithm. However, because the keystream is pseudorandom, and not truly random, the security associated with the one-time pad cannot be applied and it is quite possible for a stream cipher to be completely insecure.

Types of stream ciphers

A stream cipher generates successive elements of the keystream based on an internal state. This state is updated in two ways:

- If the state changes independently of the plaintext or ciphertext messages, the cipher is classified as a synchronous stream cipher.

- If the state is updated based on previous changes of the ciphertext digits, the cipher is classified as a self-synchronising stream ciphers.

Synchronous stream ciphers

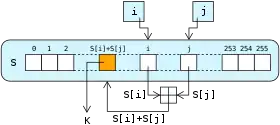

In a synchronous stream cipher a stream of pseudo-random digits is generated independently of the plaintext and ciphertext messages, and then combined with the plaintext (to encrypt) or with the ciphertext (to decrypt). In the most common form, binary digits(bits) are used, and the keystream is combined with the plaintext using the exclusive or operation (XOR). This is termed a binary additive stream cipher.

In a synchronous stream cipher, the sender and receiver must be synchronous for decryption to be successful. If digits are added or removed from the message during transmission, synchronisation is lost. To restore synchronisation, various offsets can be tried systematically to obtain the correct decryption. Another approach is to mark the ciphertext with markers at regular points in the output.

If, however, a digit is corrupted in transmission, rather than added or lost, only a single digit in the plaintext is affected and the error does not spread to other parts of the message. This property is useful when the transmission error rate is high; however, it makes it less likely that the error would be detected without further mechanisms. Moreover, because of this property, synchronous stream ciphers are very susceptible to active attacks — if an attacker can change a digit in the ciphertext, he might be able to make predictable changes to the corresponding plaintext bit; for example, flipping a bit in the ciphertext causes the same bit to be flipped(Toggled) in the plaintext.

Self-synchronizing stream ciphers

Self-synchronizing stream ciphers is another technique that uses part of the previous N ciphertext digits to compute the keystream. Such schemes are known also as asynchronous stream ciphers or ciphertext autokey (CTAK). The idea of self-synchronization was patented in 1946, and has the advantage that the receiver will automatically synchronise with the keystream generator after receiving N ciphertext digits, making it easier to recover if digits are dropped or added to the message stream. Single-digit errors are limited in their effect, affecting only up to N plaintext digits. It is somewhat more difficult to perform active attacks on self-synchronising stream ciphers rather than synchronous counterparts.

An example of a self-synchronising stream cipher is a block cipher in cipher-feedback mode (CFB).

Linear feedback shift register-based stream ciphers

Binary stream ciphers are often constructed using linear feedback shift registers (LFSRs) because they can be easily implemented in hardware and can be quickly analysed mathematically. However, the use of LFSRs only is insufficient to provide good security. Various schemes have been designed to increase the security of LFSRs.

Non-linear combining functions

Because LFSRs are inherently linear, one technique for removing the linearity is to feed the outputs of a group of parallel LFSRs into a non-linear Boolean function to form a combination generator. Various properties of such a combining function are important for ensuring the security of the resultant scheme, for example, in order to avoid correlation attacks.

Clock-controlled generators

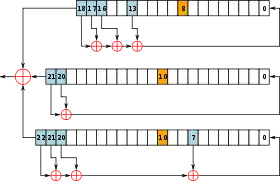

Normally LFSRs are stepped regularly. One technique to introducing non-linearity is to have the LFSR clocked irregularly, controlled by the output of a second LFSR. Such generators include the stop-and-go generator, the alternating step generator and the shrinking generator.

The stop-and-go generator (Beth and Piper, 1984) consists of two LFSRs. One LFSR is clocked if the output of a second is a "1", otherwise it repeats its previous output. This output is then (in some versions) combined with the output of a third LFSR clocked at a regular rate.

The shrinking generator uses a different technique. Two LFSRs are used, both clocked regularly in the following way:

- If the output of the first LFSR is "1", the output of the second LFSR becomes the output of the generator.

- If the output of the first LFSR "0", the output of the second is discarded, and no bit is output by the generator.

This technique suffers from timing attacks on the second generator, since the speed of the output is variable in a manner that depends on the second generator's state. This can be improved by buffering the output.

Filter generator

Another approach to improving the security of an LFSR is to pass the entire state of a single LFSR into a non-linear filtering function.

Other designs

Instead of a linear driving device, one may use a nonlinear update function. For example, Klimov and Shamir proposed triangular functions (T-Functions) with a single cycle on n bit words.

Security

To be secure, the period of the keystream (the number of digits output before the stream repeats itself) needs to be large enough. If the sequence repeats, then the overlapping ciphertexts can be aligned against each other "in depth", and there are techniques which allow extraction of the plaintext form ciphertexts generated using these methods.

Usage

Stream ciphers are often used in applications where plaintext comes in quantities of unknowable length as in secure wireless connections. If a block cipher were to be used in this type of application, the designer would need to choose either transmission efficiency or implementation complexity, since block ciphers cannot directly work on blocks shorter than their block size. For example, if a 128-bit block cipher received separate 32-bit bursts of plaintext, three quarters of the transmitted data need padding. Block ciphers must be used in ciphertext stealing or residual block termination mode to avoid padding, while stream ciphers eliminate this issue by operating on the smallest transmitted unit (usually bytes).

Another advantage of stream ciphers in military cryptography is that the cipher stream can be generated by an encryption device that is subject to strict security measures then fed to other devices, e.g. a radio set, which will perform the xor operation as part of their function. The other device can be designed for used in less securely environments.

RC4 is the most widely used stream cipher in software; others include: A5/1, A5/2, Chameleon, FISH, Helix, ISAAC, MUGI, Panama, Phelix, Pike, SEAL, SOBER, SOBER-128 and WAKE.

Comparison Of Stream Ciphers

| Stream Cipher |

Creation Date |

Speed (cycles/byte) |

(bits) | Attack | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Key-Length |

Initialization vector | Internal State |

Best Known | Computational Complexity | |||

| A5/1 | 1989 | Voice (Wphone) | 54 | 114 | 64 | Active KPA OR KPA Time-Memory Tradeoff |

~2 seconds OR 239.91 |

| A5/2 | 1989 | Voice (Wphone) | 54 | 114 | 64? | Active | 4.6 milliseconds |

| FISH | 1993 | Quite Fast (Wsoft) | Huge | ? | ? | Known-plaintext attack | 211 |

| Grain | Pre-2004 | Fast | 80 | 64 | 160 | Key-Derivation | 243 |

| HC-256 | Pre-2004 | 4 (WP4) | 256 | 256 | 65536 | ? | ? |

| ISAAC | 1996 | 2.375 (W64-bit) - 4.6875 (W32-bit) |

8-8288 usually 40-256 |

N/A | 8288 | (2006) First-round Weak-Internal-State-Derivation |

4.67×101240 (2001) |

| MUGI | 1998-2002 | ? | 128 | 128 | 1216 | N/A (2002) | ~282 |

| PANAMA | 1998 | 2 | 256 | 128? | 1216? | Hash Collisions (2001) | 282 |

| Phelix | Pre-2004 | up to 8 (Wx86) | 256 + a 128-bit Nonce | 128? | ? | Differential (2006) | 237 |

| Pike | 1994 | 0.9 x FISH (Wsoft) | Huge | ? | ? | N/A (2004) | N/A (2004) |

| Py | Pre-2004 | 2.6 | 8-2048? usually 40-256? |

64 | 8320 | Cryptanalytic Theory (2006) | 275 |

| Rabbit | 2003-Feb | 3.7(WP3)-9.7(WARM7) | 128 | 64 | 512 | N/A (2006) | N/A (2006) |

| RC4 | 1987 | Impressive | 8-2048 usually 40-256 |

8 | 2064 | Shamir Initial-Bytes Key-Derivation OR KPA | 213 OR 233 |

| Salsa20 | Pre-2004 | 4.24 (WG4) - 11.84 (WP4) |

128 + a 64-bit Nonce | 512 | 512 + 384 (key+IV+index) | Differential (2005) | N/A (2005) |

| Scream | 2002 | 4 - 5 (Wsoft) | 128 + a 128-bit Nonce | 32? | 64-bit round function | ? | ? |

| SEAL | 1997 | Very Fast (W32-bit) | ? | 32? | ? | ? | ? |

| SNOW | Pre-2003 | Very Good (W32-bit) | 128 OR 256 | 32 | ? | ? | ? |

| SOBER-128 | 2003 | ? | up to 128 | ? | ? | Message Forge | 2−6 |

| SOSEMANUK | Pre-2004 | Very Good (W32-bit) | 128 | 128 | ? | ? | ? |

| Trivium | Pre-2004 | 4 (Wx86) - 8 (WLG) | 80 | 80 | 288 | Brute force attack (2006) | 2135 |

| Turing | 2000-2003 | 5.5 (Wx86) | ? | 160 | ? | ? | ? |

| VEST | 2005 | 42 (WASIC) - 64 (WFPGA) |

Variable usually 80-256 |

Variable usually 80-256 |

256 - 800 | N/A (2006) | N/A (2006) |

| WAKE | 1993 | Fast | ? | ? | 8192 | CPA & CCA | Vulnerable |

| Stream Cipher |

Creation Date |

Speed (cycles/byte) |

(bits) | Attack | |||

| Effective Key-Length |

Initialization vector | Internal State |

Best Known | Computational Complexity | |||

Related pages

References

- Matt J. B. Robshaw, Stream Ciphers Technical Report TR-701, version 2.0, RSA Laboratories, 1995 (PDF) Archived 2008-07-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Thomas Beth and Fred Piper, The Stop-and-Go Generator. EUROCRYPT 1984, pp 88–92.

Other websites

- RSA technical report on stream cipher operation. Archived 2008-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Analysis of Lightweight Stream Ciphers (thesis by S. Fischer). Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine