Richard I, Duke of Normandy

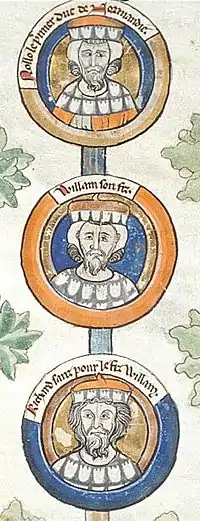

Richard I of Normandy (933–996), also known as Richard the Fearless (French, Sans Peur), was the "Duke of Normandy" from 942 to 996.[lower-alpha 1] Richard made Normandy into a feudal society where he owned all the land. His followers held on to the lands given them by remaining loyal to him. He made Normandy a much stronger a power in western France.

Early Career

Richard was the son of William Longsword, princeps[3] or ruler of Normandy. His mother's name was Sprota.[4] She was a Breton prisoner captured in war who William later married.[lower-alpha 2][7] William Longsword was told of the birth of a son after the battle with Riouf and other viking rebels. But he kept this a secret until a few years later. When he first met his son he kissed him and made him the heir to Normandy. William then sent Richard to be cared for in Bayeux.[8]

When his father died, Richard was only 10 years old (he was born in 933).[4] King Louis IV of France decided to take charge of Normandy himself. The king placed the young duke in the custody of the count of Ponthieu.[9] Then the king gave the lands in lower Normandy to Hugh the Great. Louis kept Richard a prisoner at Lâon.[10] Fearing the king was going to harm the boy Osmond de Centville, Bernard de Senlis (who had been a companion of Richard's grandfather Rollo), Ivo de Bellèsme, and Bernard the Dane freed Richard.[11]

Duke of Normandy

In 946, Richard agreed to be a ward of Hugh, Count of Paris. He then allied himself with the Norman and Viking leaders. Together they drove Louis out of Rouen and took back Normandy by 947.[12] In 962 Theobald I, Count of Blois, attacked Rouen. But Richard's army defeated them.[13] Lothair king of West Francia stepped in to prevent any more war between the two.[14] For the rest of his reign Richard chose not to make Normandy bigger. Instead he worked on making Normandy stronger.[15]

Richard used marriages to build strong alliances. His marriage to Emma gave him a connection to the Capet family. His wife Gunnor was from a rival Viking group in the Cotentin. His marriage to her gave him support from her family. Her sisters married several of Richard's loyal followers.[16] Also Richard's daughters provided valuable marriage alliances with powerful counts as well as to the king of England.[16] Richard also made sure the church and the great monasteries were doing well. His reign was marked by a long period of peace and tranquility.[17] Richard died in Fecamp, Normandy, on 20 November 996.[18]

Marriages

William married first (960)to Emma, daughter of Hugh "The Great" of France.[4] They were promised to each other when both were very young. She died after 19 March 968, before they had any children.[4]

Richard had children with his concubine Gunnora. Richard later married her to make their children legitimate:[4]

- Richard II "the Good", Duke of Normandy[4]

- Robert II, Archbishop of Rouen, Count of Évreux[4]

- Mauger, Earl of Corbeil[4]

- Emma of Normandy, wife of two kings of England[4]

- Maud of Normandy, wife of Odo II, Count of Blois, Champagne and Chartres[4]

- Hawise of Normandy married Geoffrey I, Duke of Brittany[4]

- Papia of Normandy

- William, Count of Eu

Illegitimate Children

Richard was known to have had several other concubines and had children with many of them. Known children are:

Notes

- The title "Duke of Normandy" is used here as a title of convenience by historians.[1] While Richard's father was called the Count of Rouen he also used the title Count of Normandy. Richard I styled himself "count and consul" in a charter for Fecamp.[2]

- This was a type of marriage that did not have a church ceremony. It was a common type of marriage at this time in Normandy and elsewhere.[5] After William was killed, Sprota became the wife of Esperleng, a wealthy miller; Rodulf of Ivry was their son and Richard's half-brother.[6]

References

- François Neveux, The Normans; The Conquests that Changed the Face of Europe, trans. Howard Curtis (London: Constable & Robinson Ltd., 2008), p. 69

- David Douglas, 'The Earliest Norman Counts', The English Historical Review, Vol. 61, No. 240 (May, 1946), p. 130

- The Annals of Flodoard of Reims; 916–966, ed. & trans. Steven Fanning and Bernard S. Bachrach (University of Toronto Press, 2011), p. 32

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln|Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band II (Marburg, Germany: J. A. Stargardt, 1984), Tafel 79

- Edward Augustus Freeman, The History of the Norman Conquest of England; Its Causes and its Results, Vol. I (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1877), pp. 624-25

- Detlev Schwennicke, Europäische Stammtafeln: Stammtafeln zur Geschichte der Europäischen Staaten, Neue Folge, Band III Teilband 4 (Marburg, Germany: J. A. Stargardt, 1989), Tafel 694A

- The Normans in Europe, ed. & trans. Elisabeth van Houts (Manchester University Press, 2000), p. 47 n. 77

- Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 95

- Pierre Riché, The Carolingians; A Family who Forged Europe, trans. Michael Idomir Allen (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1993) pp. 262–3

- Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 80

- The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vatalis, and Robert of Torigni, Vol. I, ed. & trans. Elisabeth M.C. van Houts (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992) pp. 103, 105

- Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), pp. 85–6

- The Annals of Flodoard of Reims; 916–966, ed. & trans. Steven Fanning and Bernard S. Bachrach (University of Toronto Press, 2011), p. 66

- Pierre Riché, The Carolingians; A Family who Forged Europe, trans. Michael Idomir Allen (University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1993), p. 265

- Eleanor Searle, Predatory Kinship and the Creation of Norman Power, 840–1066 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988), p. 89

- A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World, ed. Christopher Harper-Bill, Elisabeth Van Houts (The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, 2007), p. 27

- François Neveux. A Brief History of The Normans (Constable & Robbinson, Ltd, London, 2008), pp. 73. 74

- François Neveux. A Brief History of The Normans (Constable & Robbinson, Ltd, London, 2008), p. 74

- David Douglas, 'The Earliest Norman Counts', The English Historical Review, Vol.61, No. 240 (May 1946), p. 140