Northwest Highlands

_Named_(HR).png.webp)

divisions of Scotland

The Northwest Highlands are the northern third of Scotland, which is separated from the Grampian Mountains by the Great Glen. The Caledonian Canal, which extends from Loch Linnhe in the west, via Loch Ness to the Moray Firth in the north splits this area from the rest of the country.

The Highlands are formed on Lewisian gneiss, the oldest layers of rock in Scotland. There are impressive rock islands of dark red or gray Torridonian sandstone which stick up out of the gneiss. Some of the peaks, such as Beinn Eighe and Canisp, are topped with light gray or white Cambrian quartzite.

The city of Inverness, known as the "Capital of the Highlands", is by far the largest settlement in the region. It is the administrative centre for the Highland Council area.

Climate

This area's climate varies with altitude. It has wet, warm summers, average under 17C (62.6F). The winters are mild at low altitude but become snowier and colder with higher elevation.

Mountains may have up to 6 months of snow. Naturally the area would be a vast birch, pine and montane shrub forest, such as those surviving in Glen Affric. Snow may lie from more than a month to 105 days, but not at coastal or very low altitudes.

Geography

The region has steep, glacier-carved mountains, valleys and interspersed plains. Many islands (which also vary widely) lie off the coast.

Elevations of around 800 metres or over are common, as are mountains exceeding 1000 metres.

The Northwest Highlands are typically not quite as cold as the Cairngorms. Considering its terrain and its latitude of about 57 to 58 degrees North, the area is surprisingly warm: this is due to the mild influence of the Gulf Stream. The aurora borealis is sometimes visible on winter nights, weather permitting, especially at the climax of the 11 year cycle.

Bordering the region to the north east is the lowland area of Caithness.

The region has a very low population density. Significant settlements are Kyle of Lochalsh, Mallaig, Dingwall, Dornoch, and Ullapool.

Geology

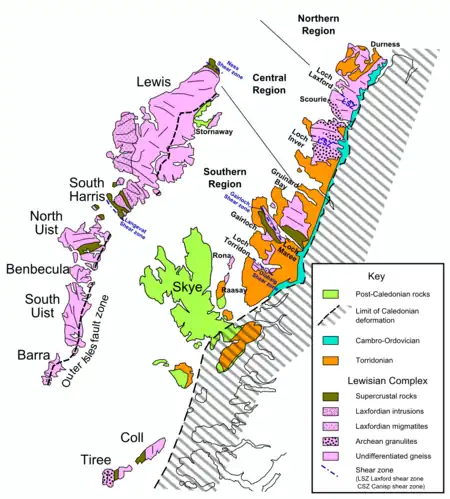

Geologically, the Northwest Highlands includes the Hebrides, especially Lewis and Harris.

Lewisian complex

The main outcrops of the Lewisian complex are on the islands of the Outer Hebrides, including Lewis, from which the complex takes its name.[1] It is also exposed on several islands of the Inner Hebrides, small islands north of the Scottish mainland and forms a coastal strip on the mainland.

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian Gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean Terrane. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleoproterozoic age, ranging from 3.0–1.7 billion years ago.

They form the basement on which later sediments were deposited. The Lewisian consists mainly of granitic gneisses. Rocks of the Lewisian complex were caught up in the Caledonian orogeny, appearing in the hanging walls of many of the thrust faults formed during the late stages of this tectonic event.

Its presence at the seabed and beneath Palaeozoic and Mesozoic strata west of Shetland has been confirmed by shallow boreholes and hydrocarbon exploration wells.[2]

Basement rocks of similar type are found at the base of the Moine Supergroup, sometimes with well-preserved unconformable contacts. These form part of the Lewisian, so the Lewisian complex extends at least as far southeast as the Great Glen Fault.[1]

Calidonian orogeny

The Highlands are formed from the remains of the old Caledonian mountain range in northern Europe, the Caledonian orogeny. This included what is now Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden), Scotland, Wales, Normandy and Brittany in France.

References

- Park, R.G.; Stewart, A.D.; Wright, D.T. (2003). "3. The Hebridean terrane". In Trewin N.H. (ed.). The Geology of Scotland. London: Geological Society. pp. 45–61. ISBN 978-1862391260. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- Kirton, S.R.; Hitchen, K. (1987). "Timing and style of crustal extension N of the Scottish mainland". In Coward M.P., Dewey J.F. & Hancock P.L. (ed.). Continental Extensional Tectonics. Special Publications. Vol. 28. London: Geological Society. pp. 501–510. ISBN 9780632016051.