Itanium

Itanium (/aɪˈteɪniəm/ eye-TAY-nee-əm) is a type of Intel microprocessor with 64-bit chip architecture (not related to the by now mainstream 64-bit CPUs made by Intel and others). Itanium processors are sometimes used today for servers. Itanium processors were originally designed by HP and Intel with Intel making producing them, and several manufacturers of systems used them; nowhere as many systems used as originally hoped for. HP still supports systems using these chips.

Itanium 2 processor | |

| Produced | From mid-2001 to present |

|---|---|

| Common manufacturer(s) |

|

| Max. CPU clock rate | 733 MHz to 2.53 GHz |

| FSB speeds | 300 MHz to 667 MHz |

| Instruction set | Itanium |

| Number of cores | 1, 2, 4 or 8 |

Intel officially announced the end of life and product discontinuance of the Itanium CPU family on January 30, 2019.[1]

Market reception

Powerful-type server market

When first released in 2001, Itanium's speed was disappointing compared to other processor types.[2][3] Using existing x86 applications and operating systems was especially bad, with one test in 2001 showing that it was as fast as a 100 MHz Pentium (1.1 GHz Pentiums were on the market at that time).[4] Itanium did not have success compared to IA-32 or RISC, and was even worse when x86-64 was released, which worked with older x86 applications.

In an article from 2009 about the history of Itanium — "How the Itanium Killed the Computer Industry" — journalist John C. Dvorak reported "This continues to be one of the great fiascos [bad situations] of the last 50 years" .[5] Technology writer Ashlee Vance wrote that slowness in speed and release "turned the product into a joke in the chip industry."[6] In an interview, Donald Knuth said "The Itanium approach...was supposed to be so terrific—until it turned out that the wished-for compilers were basically impossible to write."[7]

Both Red Hat and Microsoft said that they would stop allowing Itanium to be used with their operating systems.[8][9] However, other Linux distributions such as Gentoo and Debian were still available for Itanium. On March 22, 2011, Oracle said they would no longer support Itanium, but support for their existing products would continue.[10] In October 2013, Oracle said they would release Oracle Database 12.1.0.1.0 on HP-UX Itanium 11.31 by early 2014.[11]

A past Intel company official said that Itanium had become profitable (Able to make a lot of money) for Intel in late 2009.[12] In 2009 and later, Itanium was mostly used on servers by HP, which made 95% of Itanium servers,[6] so the primary operating system for Itanium was HP-UX. On March 22, 2011, Intel said they will keep supporting Itanium entirely with many new Itanium chips being created and on-time.[13]

Other markets

Although Itanium did do well with high-end computing, Intel wanted it to have more usage compared to the original x86 architecture.[14]

AMD decided on an easier idea, creating x86-64, a 64-bit addition to the x86 architecture, which Microsoft soon supported in Microsoft Windows, so Intel had to include the same type of 64-bit addition in Intel's x86 processors.[15] x86-64 can use existing 32-bit applications at full hardware speed, but has 64-bit memory addressing and other additions to new applications.[6] This architecture has now become the most used 64-bit architecture in the desktop and laptop market, with the 64-bit ARMv8 architecture powering many mobile devices, used in today's iPhones, iPads, iPod Touches, and now many Android phones and tablets such as the Nexus 6P and Nexus 9. Ssome Itanium-based workstations were introduced by companies such as SGI, but they are no longer available. Because AMD made the first x86-64 chip, the architecture is commonly referred to as "amd64" inside of operating systems.

History

Development: 1989–2000

In 1989, HP thought Reduced Instruction Set Computing (RISC) architectures were stuck at one instruction per cycle. HP researchers tried to create a new type of processor architecture, later called Explicitly Parallel Instruction Computing (EPIC), that allows the processor to use many instructions in each clock cycle. EPIC uses a form of very long instruction word architecture, in which 1 instruction word had many instructions. With EPIC, the compiler checks which instructions can be used at the same time, so the processor can run the instructions without needing complicated methods to see which instructions to use at the same time.[18] The idea is to allow better inspection of the code at the time of compile to check for additional opportunities for multiple executions at once, and to simplify processor design and save electricity by removing the need for runtime scheduling instructions.

HP thought that it was not good for individual enterprise system companies like HP to make proprietary processors, so HP worked with Intel in 1994 to create the IA-64 architecture, made with EPIC's ideas. Intel wanted to make a large effort in creating IA-64 in the expectation that the resulting processor would be used by most enterprise systems. HP and Intel had a large design effort to make the first Itanium product, Merced, in 1998.[18]

During creation, Intel, HP, and other industry analysts thought that IA-64 would be very popular in servers, workstations, and desktops, and one day replace RISC and Complex Instruction Set Computing (CISC) architectures for multi-purpose applications.[2][3] Compaq and Silicon Graphics stopped working on their Alpha and MIPS architectures to move to the Itanium architecture.[19]

Many groups created operating systems for Itanium, including Microsoft Windows, OpenVMS, Linux, and UNIX types such as HP-UX, Solaris,[20][21][22] Tru64 UNIX,[19] and Monterey/64[23] (the last three were never finished). By 1997, many found that the Itanium architecture and the compiler were more difficult to use than they thought.[24] Technology issues such as the very high transistor counts needed for the large instruction words and the large caches. There were also problems with the project, as the two parts of the team used different methods and had slightly different priorities. Because Merced was the first EPIC processor, its creation had more problems than the team had thought. In addition, the EPIC concept requires different compiler abilities that had never been created before, so more research was needed.

Intel announced the name of the processor, Itanium, on October 4, 1999.[25] In only a few hours, the name Itanic had been used as a joke, (a reference to Titanic, the "unsinkable" ship that sank in 1912 ("Itanium + Titanic = Itanic")).[26] "Itanic" has also been used by The Register,[27] and others,[28][29][30] to say the multi-billion-dollar investment in Itanium, and the early demand with it, would mean nothing because they thought Itanium was going to fail.

Itanium (Merced): 2001

Itanium processor | |

| Produced | From June 2001 to June 2002 |

|---|---|

| Common manufacturer(s) |

|

| Max. CPU clock rate | 733 MHz to 800 MHz |

| FSB speeds | 266 MT/s |

| Instruction set | Itanium |

| Number of cores | 1 |

| L2 cache | 96 KB |

| L3 cache | 2 or 4 MB |

| Socket(s) |

|

| Core name(s) |

|

By the time Itanium was released in June 2001, its performance was not superior to competing RISC and CISC processors.[31] Itanium competed with low-power systems (primarily 4-CPU and small systems) with servers based on x86 processors, and with high-power such as with IBM's POWER architecture and Sun Microsystems' SPARC architecture. Intel shifted Itanium to working with the high-power business and HPC computing, trying to copy x86's successful market (i.e., 1 architecture, many system vendors). The success of the 1st processor version was only with replacing PA-RISC in HP systems, Alpha in Compaq systems and MIPS in SGI systems, but IBM also made a supercomputer based on this architecture.[32] POWER and SPARC were strong, and the x86 architecture grew more into the enterprise space, because of easier scaling and very large install base.

Only a few thousand systems using the 1st Itanium processor, Merced, were sold, because of poorer performance, high cost and less Itanium-made software.[33] Intel saw that Itanium required more native software to work well, so Intel made thousands of systems for independent software vendors to help them make Itanium software. HP and Intel brought the 2nd Itanium processor, Itanium 2, to market a year later.

Itanium 2: 2002–2010

Itanium 2 processor | |

| Produced | From 2002 to 2010 |

|---|---|

| Designed by | Intel |

| Common manufacturer(s) |

|

| Max. CPU clock rate | 900 MHz to 2.53 GHz |

| Instruction set | Itanium |

| Number of cores | 1, 2, 4 or 8 |

| L2 cache | 256 KB on Itanium2 256 KB (D) + 1 MB(I) or 512 KB (I) on (Itanium2 9x00 series) |

| L3 cache | 1.5-32 MB |

| Socket(s) |

|

| Core name(s) |

|

The Itanium 2 processor was released in 2002, for enterprise servers and not all of high-power computing. The 1st version of Itanium 2, code-named McKinley, was created by HP and Intel. It fixed many of the problems of the 1st Itanium processor, which were mostly caused by a bad memory subsystem. McKinley had 221 million transistors (25 million of them were for logic), and was 19.5 mm by 21.6 mm (421 mm2) and was created with a 180 nm design process, and a CMOS process with 6 layers of aluminium.[34]

In 2003, AMD released the Opteron, which implemented the first x86-64 architecture (called AMD64 at the time). Opteron was much more successful because it was an easy upgrade from x86. Intel implemented x86-64 in its Xeon processors in 2004.[19]

Intel released a new Itanium 2 processor, code-named Madison, in 2003. Madison used a 130 nm process and was the foundation of all new Itanium processors until June 2006.

In March 2005, Intel announced that it was working on a new Itanium processor, code-named Tukwila, to be released in 2007. Tukwila would have 4 processor cores and would replace the Itanium bus with a new Common System Interface, which would also be used by a new Xeon processor.[35]Later in that year, Intel changed Tukwila's release date to late 2008.[36]

In November 2005, the largest Itanium server makers worked with Intel and many software vendors to create the Itanium Solutions Alliance, to promote the architecture and speed up software porting.[37] The Alliance said that its members would invest $10 billion in Itanium solutions by the end of the decade.[38]

In 2006, Intel delivered Montecito (marketed as the Itanium 2 9000 series), a 2-core processor that had approximately 2x performance and 20% less energy usage.[39]

Intel released the Itanium 2 9100 series, codenamed Montvale, in November 2007.[40] In May 2009, the release for Tukwila, Montvale's successor, was changed again, with release to OEMs planned for the first quarter of 2010.[41]

Itanium 9300 (Tukwila): 2010

The Itanium 9300 series processor, code-named Tukwila, was released on February 8, 2010, with greater performance and memory.[42]

Tukwila uses a 65 nm process, has between two and four cores, up to 24 MB CPU cache, Hyper-Threading technology and new memory controllers. It also has double-device data correction, which helps to fix memory issues. Tukwila also has Intel QuickPath Interconnect (QPI) to replace the Itanium bus architecture. It has a maximum inner-processor bandwidth of 96 GB/s and a maximum memory bandwidth of 34 GB/s. With QuickPath, the processor has built-in memory controllers, which control the memory using QPI interfaces to communicate with other processors and I/O hubs. QuickPath is also used with Intel processors using the Nehalem architecture, so that Tukwila and Nehalem might be able to use the same chipsets.[43] Tukwila incorporates four memory controllers, each of which supports multiple DDR3 DIMMs via a separate memory controller.[44]

Itanium 9500 (Poulson): 2012

The Itanium 9500 series processor, code-named Poulson, is the follow-on processor to Tukwila and was released on November 8, 2012.[45] Intel says it skips the 45 nm process technology and uses the 32 nm process technology instead; it features 8 cores, has a 12-wide issue architecture, multi-threading additions, and new instructions for parallelism, including virtualization.[43][46][47] The Poulson L3 cache size is 32 MB. L2 cache size is 6 MB, 512 I KB, 256 D KB per core.[48] Poulson's size is 544 mm², less than Tukwila's size (698.75 mm²).[49][50]

Market share

In comparison with its Xeon server processors, Itanium has never been a large product for Intel. Intel does not release production numbers. One industry analyst estimated that the production rate was 200,000 processors per year in 2007.[51]

According to Gartner, in 2008, HP had 95% of Itanium sales.[6] HP's Itanium system sales were at $4.4 Billion at the end of 2008, and $3.5 Billion by the end of 2009,[52] compared to a 35% decline in UNIX system revenue for Sun and an 11% drop for IBM, with an x86-64 server revenue increase of 14% during this period.

In December 2012, IDC released a research report stating that Itanium server shipments would remain flat through 2016, with annual shipment of 26,000 systems (a decline of over 50% compared to shipments in 2008).[53]

Hardware support

Systems

| Company | Latest product | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| name | from | to | name | CPUs |

| Compaq | 2001 | 2001 | ProLiant 590 | 1–4 |

| IBM | 2001 | 2005 | x455 | 1–16 |

| Dell | 2001 | 2005 | PowerEdge 7250 | 1–4 |

| Hitachi | 2001 | 2008 | BladeSymphony 1000 | 1–8 |

| Unisys | 2002 | 2009 | ES7000/one | 1–32 |

| SGI | 2001 | 2011 | Altix 4000 | 1–2048 |

| Fujitsu | 2005 | 2011 | PRIMEQUEST | 1–32 |

| HP | 2001 | now | Integrity | 1–256 |

| Bull | 2002 | now | NovaScale 9410 | 1–32 |

| NEC | 2002 | now | nx7700i | 1–256 |

| Inspur | 2010 | now | TS10000 | 2-1024 |

| Huawei | 2012 | now | ???? | ???? |

As of 2015, only a few providers have Itanium systems, such as HP, Bull, NEC, Inspur and Huawei. Intel offers a chassis that can be used by system integrators to build Itanium systems.[54] HP sold 7,200 systems in the first quarter of 2006.[55] Most Itanium systems sold are enterprise servers and machines for large-scale technical computing, with each system costing about US $200,000. A typical system uses eight or more Itanium processors.

Chipsets

The Itanium bus communicates with the rest of the system. Enterprise server makers differentiate their systems by making their own chipsets that interface the processor to memory, interconnections, and peripheral controllers. The chipset is the heart of the system-level architecture for each system design. Creation of a chipset costs tens of millions of dollars and represents a major commitment to the use of the Itanium. IBM created a chipset in 2003, and Intel in 2002, but neither of them developed chipsets to support technologies such as DDR2 or PCI Express.[56] Chipsets for Itanium supporting such technologies were manufactured by HP, Fujitsu, SGI, NEC, and Hitachi.

The "Tukwila" Itanium processor model had been designed to share a common chipset with the Intel Xeon processor EX (Intel's Xeon processor designed for four processor and larger servers). The goal is to streamline system development and reduce costs for server OEMs, many of whom develop both Itanium- and Xeon-based servers. However, in 2013, this goal was pushed back to "evaluated for future implementation opportunities".[57]

Software support

Itanium is or was supported (i.e. Windows version can no longer be bought) by the following operating systems:

- Windows family

- Windows XP 64-Bit Edition (Unsupported; first Windows edition to support)

- Windows Server 2003 (Unsupported)

- Windows Server 2008 (Extended support until January 14, 2020.[58] Extended support will only receive bug fixes and no new features, including support for future CPUs. This is the last version of Windows still with support for Itanium. Windows Server 2008 and Server 2008 R2 got a security update in middle of 2018.[59])

- Windows Server 2008 R2 (This is the last version of Windows to support Itanium.[60])

- Linux distributions

- FreeBSD[64][65] (unsupported; was supported in 10.4[66] (to October 2018 EOL) as: "Tier 2 through FreeBSD 10. Unsupported after."[67])

- NetBSD (development branch only, but "no formal release is available".[68])

- OpenVMS I64 (to 2020[69]); an Intel 64 (x86-64) port is being developed.[70]

- NEC ACOS-4[71] (in late September 2012, NEC announced a return from IA-64 to the previous NOAH line of proprietary mainframe processors for ACOS-4.[72])

Microsoft announced that Windows Server 2008 R2 would be the last version of Windows Server to support the Itanium (support started with XP), and that it would also discontinue development of the Itanium versions of Visual Studio and SQL Server.[8] Likewise, Red Hat Enterprise Linux 5 (first released in March 2007) was the last Itanium edition of Red Hat Enterprise Linux[9]

In late September 2012, NEC announced a return from IA-64 to the previous NOAH line of proprietary mainframe processors, now produced in a quad-core variant on 40 nm, called NOAH-6.[73]

To allow more software to run on the Itanium, Intel supported the development of compilers optimized for the platform, especially its own suite of compilers.[74][75] Starting in November 2010, with the introduction of new product suites, the Intel Itanium Compilers were no longer bundled with the Intel x86 compilers in a single product. Intel offers Itanium tools and Intel x86 tools, including compilers, independently in different product bundles.GCC,[76][77] Open64 and Microsoft Visual Studio 2005 (and later)[78] are also able to produce machine code for Itanium. According to the Itanium Solutions Alliance over 13,000 applications were available for Itanium-based systems in early 2008,[79] though Sun has contested Itanium application counts in the past.[80] The ISA also supported Gelato, an Itanium HPC user group and developer community that ported and supported open-source software for Itanium.[81]

Competition

Itanium is aimed at the enterprise server and high-performance computing (HPC) markets. Other enterprise- and HPC-focused processor lines include Oracle Corporation's SPARC M7, Fujitsu's SPARC64 X+ and IBM's POWER8. Measured by quantity sold, Itanium's most serious competition comes from x86-64 processors including Intel's own Xeon line and AMD's Opteron line. Since 2009, most servers were being shipped with x86-64 processors.[52]

In 2005, Itanium systems accounted for about 14% of HPC systems revenue, but the percentage declined as the industry shifts to x86-64 clusters for this application.[82]

An October 2008 paper by Gartner, on the Tukwila processor stated that "...the future roadmap for Itanium looks as strong as that of any RISC peer like Power or SPARC."[83]

Supercomputers and high-performance computing

An Itanium-based computer first appeared on the list of the TOP500 supercomputers in November 2001.[32] The best position ever achieved by an Itanium 2 based system in the list was #2, achieved in June 2004, when Thunder entered the list with an Rmax of 19.94 Teraflops. In November 2004, Columbia entered the list at #2 with 51.8 Teraflops, and there was at least one Itanium-based computer in the top 10 from then until June 2007. The peak number of Itanium-based machines on the list occurred in the November 2004 list, at 84 systems (16.8%); by June 2012, this had dropped to one system (0.2%),[84] and no Itanium system remained on the list in November 2012.

Processors

Released processors

The Itanium processors show a progression in capability. Merced was a proof of concept. McKinley dramatically improved the memory hierarchy and allowed Itanium to become reasonably competitive. Madison, with the shift to a 130 nm process, allowed for enough cache space to overcome the major performance bottlenecks. Montecito, with a 90 nm process, allowed for a dual-core implementation and a major improvement in performance per watt. Montvale added three new features: core-level lockstep, demand-based switching and front-side bus frequency of up to 667 MHz.

| Codename | process | Released | Clock | L2 Cache/ core | L3 Cache/ processor | Bus | dies/ device | cores/ die | watts/ device | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itanium | ||||||||||

| Merced | 180 nm | 2001-06 | 733 MHz | 96 KB | none | 266 MHz | 1 | 1 | 116 | 2 MB off-die L3 cache |

| 800 MHz | 130 | 4 MB off-die L3 cache | ||||||||

| Itanium 2 | ||||||||||

| McKinley | 180 nm | 2002-07-08 | 900 MHz | 256 KB | 1.5 MB | 400 MHz | 1 | 1 | 130 | HW branchlong |

| 1 GHz | 3 MB | 130 | ||||||||

| Madison | 130 nm | 2003-06-30 | 1.3 GHz | 3 MB | 130 | |||||

| 1.4 GHz | 4 MB | 130 | ||||||||

| 1.5 GHz | 6 MB | 130 | ||||||||

| 2003-09-08 | 1.4 GHz | 1.5 MB | 130 | |||||||

| 2004-04 | 1.4 GHz | 3 MB | 130 | |||||||

| 1.6 GHz | ||||||||||

| Deerfield | September 8, 2003 | 1.0 GHz | 1.5 MB | 62 | Low voltage | |||||

| Hondo[85] | 2004-Q1 | 1.1 GHz | 4 MB | 400 MHz | 2 | 1 | 260 | 32 MB L4 | ||

| Fanwood | 2004-11-08 | 1.6 GHz | 3 MB | 533 MHz | 1 | 1 | 130 | |||

| 1.3 GHz | 400 MHz | 62? | Low voltage | |||||||

| Madison | November 8, 2004 | 1.6 GHz | 9 MB | 400 MHz | 130 | |||||

| 2005-07-05 | 1.67 GHz | 6 MB | 667 MHz | 130 | ||||||

| 2005-07-18 | 1.67 GHz | 9 MB | 667 MHz | 130 | ||||||

| Itanium 2 9000 series | ||||||||||

| Montecito | 90 nm | 2006-07-18 | 1.4 GHz | 256 KB (D)+ 1 MB (I) | 6–24 MB | 400 MHz | 1 | 2 | 104 | Virtualization, Multithread, no HW IA-32 |

| 1.6 GHz | 533 MHz | |||||||||

| Itanium 2 9100 series | ||||||||||

| Montvale | 90 nm | October 31, 2007 | 1.42–1.66 GHz | 256 KB (D)+ 1 MB (I) | 8–24 MB | 400–667 MHz | 1 | 1–2 | 75–104 | Core-level lockstep, demand-based switching |

| Itanium 9300 series | ||||||||||

| Tukwila | 65 nm | February 8, 2010 | 1.33–1.73 GHz | 256 KB (D)+ 512 KB (I) | 10–24 MB | QPI with a speed of 4.8 GT/s | 1 | 2–4 | 130–185 | A new point-to-point processor interconnect, the QPI, replacing the FSB. Turbo Boost |

| Itanium 9500 series | ||||||||||

| Poulson | 32 nm | 2012-11-08[86] | 1.73–2.53 GHz | 256 KB (D)+ 512 KB (I) | 20–32 MB | QPI with a speed of 6.4 GT/s | 1 | 4–8 | 130–170 | Doubled issue width (from 6 to 12 instructions per cycle), Instruction Replay technology, Dual-domain hyperthreading[87][88][89] |

| Codename | process | Released | Clock | L2 Cache/ core | L3 Cache/ processor | Bus | dies/ device | cores/ die | watts/ device | Comments |

Future processors

During the HP vs. Oracle support lawsuit, court documents unsealed by Santa Clara County Court judge revealed in 2008, Hewlett-Packard had paid Intel Corp. around $440 million to keep producing and updating Itanium microprocessors from 2009 to 2014. In 2010, the two companies signed another $250 million deal, which obliged Intel to continue making Itanium central processing units for HP's machines until 2017. Under the terms of the agreements, HP has to pay for chips it gets from Intel, while Intel launches Tukwila, Poulson, Kittson and Kittson+ chips in a bid to gradually boost performance of the platform.[90][91]

Kittson

Kittson is planned to follow Poulson in 2015.[92] Kittson, like Poulson, will be manufactured using Intel's 32 nm process. Few other details are known beyond the existence of the codename and the binary and socket compatibility with Poulson and Tukwila, though moving to a common socket with x86 Xeon "will be evaluated for future implementation opportunities" after Kittson.[93]

Timeline

- 1989:

- HP begins investigating EPIC.[18]

- 1994:

- June: HP and Intel announce partnership.[94]

- 1995:

- September: HP, Novell, and SCO announce plans for a "high volume UNIX operating system" to deliver "64-bit networked computing on the HP/Intel architecture".[95]

- 1996:

- 1997:

- 1998:

- March: SCO admits HP/SCO Unix alliance is now dead.

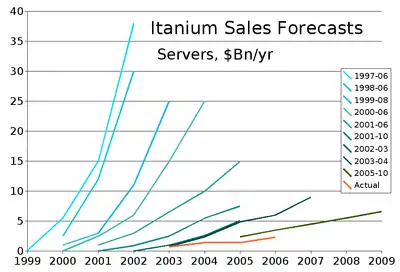

- June: IDC predicts IA-64 systems sales will reach $30bn/yr by 2001.[16]

- June: Intel announces Merced will be delayed, from second half of 1999 to first half of 2000.[98]

- September: IBM announces it will build Merced-based machines.[99]

- October: Project Monterey is formed to create a common UNIX for IA-64.

- 1999:

- 2000:

- February: Project Trillian delivers source code.

- June: IDC predicts Itanium systems sales will reach $25bn/yr by 2003.[16]

- July: Sun and Intel drop Solaris-on-Itanium plans.[100]

- August: AMD releases specification for x86-64, a set of 64-bit extensions to Intel's own x86 architecture intended to compete with IA-64. It will eventually market this under the name "AMD64".

- 2001:

- June: IDC predicts Itanium systems sales will reach $15bn/yr by 2004.[16]

- June: Project Monterey dies.

- July: Itanium is released.

- October: IDC predicts Itanium systems sales will reach $12bn/yr by the end of 2004.[16]

- November: IBM's 320-processor Titan NOW Cluster at National Center for Supercomputing Applications is listed on the TOP500 list at position #34.[32]

- November: Compaq delays Itanium Product release due to problems with processor.[101]

- December: Gelato is formed.

- 2002:

- March: IDC predicts Itanium systems sales will reach $5bn/yr by end 2004.[16]

- June: Itanium 2 is released.

- 2003:

- April: IDC predicts Itanium systems sales will reach $9bn/yr by end 2007.[16]

- April: AMD releases Opteron, the first processor with x86-64 extensions.

- June: Intel releases the "Madison" Itanium 2.

- 2004:

- February: Intel announces it has been working on its own x86-64 implementation (which it will eventually market under the name "Intel 64").

- June: Intel releases its first processor with x86-64 extensions, a Xeon processor codenamed "Nocona".

- June: Thunder, a system at LLNL with 4096 Itanium 2 processors, is listed on the TOP500 list at position #2.[102]

- November: Columbia, an SGI Altix 3700 with 10160 Itanium 2 processors at NASA Ames Research Center, is listed on the TOP500 list at position #2.[103]

- December: Itanium system sales for 2004 reach $1.4bn.

- 2005:

- January: HP ports OpenVMS to Itanium[104]

- February: IBM server design drops Itanium support.[56][105]

- June: An Itanium 2 sets a record SPECfp2000 result of 2,801 in a Hitachi, Ltd. Computing blade.[106]

- September: Itanium Solutions Alliance is formed.[107]

- September: Dell exits the Itanium business.[108]

- October: Itanium server sales reach $619M/quarter in the third quarter.

- October: Intel announces one-year delays for Montecito, Montvale, and Tukwila.[36]

- 2006:

- 2007:

- 2009:

- December: Red Hat announces that it is dropping support for Itanium in the next release of its enterprise OS, Red Hat Enterprise Linux 6.[111]

- 2010:

- 2011:

- 2012:

- February: Court papers were released from a case between HP and Oracle Corporation that gave insight to the fact that HP was paying Intel $690 million to keep Itanium on life support.[117]

- SAP discontinues support for Business Objects on Itanium.[118]

- September: In response to a court ruling, Oracle reinstitutes support for Oracle software on Itanium hardware.[119]

- 2013:

- 2014:

- December: HP announces that their next generation of Superdome X and Nonstop X servers would be equipped with Intel Xeon processors, and not Itanium. While HP continues to sell and offer support for the Itanium-based Integrity portfolio, the introduction of a model based entirely on Xeon chips marks the end of an era.[121]

References

- "Select Intel Itanium Processors and Intel Scalable Memory Buffer, PCN 116733-00, Product Discontinuance, End of Life" (PDF). Intel. January 30, 2019.

- De Gelas, Johan (November 9, 2005). "Itanium–Is there light at the end of the tunnel?". AnandTech. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- Takahashi, Dean (May 8, 2009). "Exit interview: Retiring Intel chairman Craig Barrett on the industry's unfinished business". VentureBeat. Retrieved May 17, 2009.

- "Benchmarks – Itanic 32bit emulation is 'unusable'. No kidding — slower than a P100". The Register. January 23, 2001.

- Dvorak, John C. (January 26, 2009). "How the Itanium Killed the Computer Industry". PC Mag. Archived from the original on July 14, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- Vance, Ashlee (February 9, 2009). "Ten Years After First Delay, Intel's Itanium Is Still Late". New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- Knuth, Donald E. (April 25, 2008). "Interview with Donald Knuth". InformIT. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- Reger, Dan (April 2, 2010). "Windows Server 2008 R2 to Phase Out Itanium". Windows Server Blog. Retrieved July 29, 2018.

- Timothy Prickett Morgan (December 18, 2009). "Red Hat pulls plug on Itanium with RHEL 6". The Register. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- "Oracle stops developing software for Intel's Itanium Chips". Pcworld.com. March 22, 2011. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Oracle Database 12.1.0.1.0 is planned for certification on HP-UX Itanium 11.31 Oracle November 20, 2013

- Demerjian, Charlie (May 21, 2009). "A Decade Later, Intel's Itanium Chip Makes a Profit". The Inquirer. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- Darling, Patrick. "Intel Reaffirms Commitment to Itanium". Itanium. Intel. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- Manek Dubash (July 20, 2006). "Will Intel abandon the Itanium?". Techworld. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

Once touted by Intel as a replacement for the x86 product line, expectations for Itanium have been throttled well back.

- Charlie Demerjian (September 26, 2003). "Why Intel's Prescott will use AMD64 extensions". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- "Mining Itanium". CNet News. December 7, 2005. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Shankland, Stephen (February 14, 2006). "Analyst firm offers rosy view of Itanium". CNet News. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- "Inventing Itanium: How HP Labs Helped Create the Next-Generation Chip Architecture". HP Labs. June 2001. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- "Itanium: A cautionary tale". Tech News on ZDNet. December 7, 2005. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Vijayan, Jaikumar (July 16, 1999). "ComputerWorld: Solaris for IA-64 coming this fall". Linuxtoday. Archived from the original on February 13, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Wolfe, Alexander (September 2, 1999). "Core-logic efforts under way for Merced". EE Times. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Sun Introduces Solaris Developer Kit for Intel to Speed Development of Applications On Solaris; Award-winning Sun Tools Help ISVs Easily Develop for Solaris on Intel Today". Business Wire. March 10, 1998. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- "Next-generation chip passes key milestone". CNET News.com. September 17, 1999. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- Shankland, Stephen (July 8, 1999). "Intel's Merced chip may slip further". CNET News. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Kanellos, Michael (October 4, 1999). "Intel names Merced chip Itanium". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Finstad, Kraig (October 4, 1999). "Re:Itanium". USENET group comp.sys.mac.advocacy. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- Pete Sherriff (October 28, 1999). "AMD vs Intel – our readers write". The Register. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- Berlind, David (November 30, 2001). "Interpreting McNealy's lexicon". ZDNet Tech Update. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Demerjian, Charlie (July 18, 2006). "Itanic shell game continues". The Inquirer. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Morgenson, Gretchen (October 19, 2003). "Fawning Analysts Betray Investors". New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- Linley Gwennap (June 4, 2001). "Itanium era dawns". EE Times. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2009.

- "Titan Cluster Itanium 800 MHz". TOP500 web site. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Michael Kanellos (December 11, 2001). "Itanium sales off to a slow start". CNET News.com. Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- Naffzinger, Samuel D. et al. (2002). "The implementation of the Itanium 2 microprocessor". IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, vol. 37, no. 11, pp. 1448–1460.

- Merritt, Rick (March 2, 2005). "Intel preps HyperTransport competitor for Xeon, Itanium CPUs". EE Times. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Shankland, Stephen (October 24, 2005). "Intel pushes back Itanium chips, revamps Xeon". ZDNet News. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2007.

- "Itanium Solutions Alliance". ISA web site. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Scott, Bilepo (January 26, 2006). "Computing Leaders Announce Strategy for New Era of Mission Critical Computing". Itanium Solutions Alliance Press Release. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Niccolai, James (May 20, 2008). "'Tukwila' Itanium servers due early next year, Intel says". ComputerWorld. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Gonsalves, Antone (November 1, 2007). "Intel Unveils Seven Itanium Processors". InformationWeek. Archived from the original on March 10, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- Demerjian, Charlie (May 21, 2009). "Tukwila delayed until 2010". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- New Intel Itanium Offers Greater Performance, Memory Capacity, By: Jeffrey Burt, 2010-02-08, eWeek

- Tan, Aaron (June 15, 2007). "Intel updates Itanium line with 'Kittson'". ZDNet Asia. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Stokes, Jon (February 5, 2009). "Intel delays quad Itanium to boost platform memory capacity". ars technica. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- New Intel Itanium Offers Greater Performance, Memory Capacity: Itanium 9300 Series Brings New Features (page 2) eweek.com, February 8, 2010

- "Poulson: The Future of Itanium Servers". realworldtech.com. May 18, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2011.

- "Hot Chips Poulson Disclosure Factsheet" (PDF). Intel press release. August 19, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- Riedlinger, Reid J.; Bhatia, Rohit; Biro, Larry; Bowhill, Bill; Fetzer, Eric; Gronowski, Paul; Grutkowski, Tom (February 24, 2011). "A 32nm 3.1 billion transistor 12-wide-issue Itanium® processor for mission-critical servers" (PDF). 2011 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference. pp. 84–86. doi:10.1109/ISSCC.2011.5746230. ISBN 978-1-61284-303-2. S2CID 20112763. Retrieved January 23, 2012.

- "Researchers carve CPU into plastic foil". Eetimes.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2010. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- "www.engadget.com". engadget.com. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- Patrizio, Andy (October 12, 2007). "Intel Plows Forward With Itanium". InternetNews.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- Morgan, Timothy Prickett (February 24, 2010). "Gartner report card gives high marks to x64, blades". TheRegister.com. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "Intel shifts gears on Itanium, raising questions about the server chip's future". PCWorld. February 16, 2013.

- "Intel Server System SR9000MK4U Technical Product Specification". Intel web site. January 2007. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2007.

- Vance, Ashlee (June 1, 2006). "HP grabs 90% of 'industry standard' Itanic market". The Register. Retrieved January 28, 2007.

- Shankland, Stephen (February 28, 2005). "Itanium dealt another blow". ZDNet. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- tweet_btn(), Timothy Prickett Morgan February 8, 2013 at 23:53. "Remember that Xeon E7-Itanium convergence? FUHGEDDABOUDIT". www.theregister.co.uk.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Search Product and Services Lifecycle Information - Microsoft Lifecycle".

- "Description of the security update for the Windows denial of service vulnerability in Windows Server 2008: July 10, 2018". support.microsoft.com. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- "Search Product and Services Lifecycle Information - Microsoft Lifecycle".

- "Project:IA-64".

The Gentoo/IA-64 Project works to keep Gentoo the most up to date and fastest IA-64 distribution available.

- "SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP4 for Itanium". Retrieved August 25, 2017.

- Shankland, Stephen (January 2, 2002). "TurboLinux unveils system for Intel's Itanium chip". CNet News. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- "[ia64] End of life..." freebsd.org. May 15, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "FreeBSD r268351: Remove ia64". freebsd.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "FreeBSD 10.4-RELEASE Announcement". www.freebsd.org. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- Platforms

- "NetBSD/ia64". NetBSD Foundation. Retrieved August 20, 2015.

- "HP News - HP Extends Support for OpenVMS through Year 2020". www8.hp.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- Thibodeau, Patrick (July 31, 2014). "HP gives OpenVMS new life". ComputerWorld. Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- PRODUCT BRIEF Intel® Itanium® Processor 9500 Series

- With the new CPU NOAH - 6, the next generation platform i - PX 9800 was born

- ACOS-4 news

- Barker, Matt (November 8, 2000). "Intel Announces New Compiler Versions for the Itanium and Pentium 4". Gamasutra (CMP Media Game Group). Archived from the original on August 19, 2005. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- "Intel Compilers". Intel web site. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Gelato GCC Wiki". Gelato Federation web site. Archived from the original on April 20, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Documentation at GNU.org". GNU Project web site. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Visual C++ Editions". Microsoft. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- Gonsalves, Aantone (May 19, 2008). "Computers with Next-Gen Itanium Expected Early Next Year". InformationWeek. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- "Reality Check: Straight Talk on Sun UltraSPARC vs. Itanium". January 12, 2007. Archived from the original on January 22, 2007.

- "Gelato Developing for Linux on Itanium". Gelato Federation web site. Archived from the original on May 30, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Novakovic, Nebojsa (September 25, 2008). "Supercomputing now dominated by X86 architecture". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on September 27, 2008. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- Butler, Andrew (October 3, 2008). "Preparing for Tukwila: The Next Generation of Intel's Itanium Processor Family". Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- "Processor Generation / Itanium 2 Montecito". TOP500 web site. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- HP rides Hondo to super-sized Itanium servers The Register, May 6, 2004

- "New Intel Itanium Processor 9500 Delivers Breakthrough Capabilities for Mission-Critical Computing". Intel. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- Shilov, Anton. "Intel Launches Eight-Core Itanium 9500 "Poulson" Mission-Critical Server Processor". X-bit Labs. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- Kanter, David. "Poulson: The Future of Itanium Servers". Real World Tech. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- Undy, Steve. "WHITE PAPER Intel Itanium Processor 9500 Series" (PDF). Intel. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- "HP Paid Intel $690 Million to Keep Itanium Alive - Court Findings". Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-12-06.

- McMillan, Robert (February 1, 2012). "HP Paid Intel $690 Million To Keep Itanium On Life Support". Wired – via www.wired.com.

- components, Jamie Hinks 2015-04-20T16:44:00 109Z Computing (April 20, 2015). "Intel confirms new Itanium chips are on the way". TechRadar.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - "Intel Itanium Processors Update". Intel Corporation. January 31, 2013. Retrieved February 12, 2013.

- Markoff, John (June 9, 1994). "COMPANY NEWS; Intel Forms Chip Pact With Hewlett-Packard". The New York Times. Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- "HP, Novell and SCO To Deliver High-Volume UNIX OS With Advanced Network And Enterprise Services" (Press release). Hewlett-Packard Company; Novell; SCO. September 20, 1995. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- Crothers, Brooke (October 23, 1996). "Compaq, Intel buddy up". CNET News.com. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- Veitch, Martin (May 20, 1998). "Dell will aid Intel with IA-64". ZDNet.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- Lisa DiCarlo (May 28, 1998). "Intel to delay release of Merced". PCWeek Online. Archived from the original on February 19, 2001. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- "IBM Previews Technology Blueprint For Netfinity Server Line". IBM web site. September 9, 1998. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Stephen Shankland (July 21, 2000). "Sun, Intel part ways on Solaris plans". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2007.

- Kanellos, Michael (November 14, 2001). "Itanium flunking Compaq server tests". News.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- "Thunder at TOP500". TOP500 web site. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Columbia at TOP500". TOP500 web site. Archived from the original on July 11, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- Morgan, Timothy (July 6, 2005). "HP Ramps Up OpenVMS on Integrity Servers". ITJungle.com. Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2007.

- "IBM server design drops Itanium support". TechRepublic. February 25, 2005. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- "Result submitted to SPEC on June 13, 2005 by Hitachi". SPEC web site. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- "Itanium Solutions Alliance Formed". Byte and Switch. September 26, 2005. Archived from the original on November 26, 2006. Retrieved March 24, 2007.

- Shankland, Stephen (September 15, 2005). "Dell shuttering Itanium server business". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2007.

- Preimesberger, Chris (July 19, 2006). "Is 'Montecito' Intel's Second Chance for Itanium?". eWeek. Retrieved March 23, 2007.

- "CentOS Product Specifications". Centos.org. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Ricknäs, Mikael (December 21, 2009). "Red Hat to Drop Itanium Support in Enterprise Linux 6". PC World. PCWorld Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on August 5, 2011. Retrieved March 25, 2011.

- Niccolai, James (May 8, 2009). "Microsoft Ending Support for Itanium". PCWorld. Archived from the original on April 8, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

Windows Server 2008 R2 will be the last version of Windows Server to support the Intel Itanium architecture," [...] "SQL Server 2008 R2 and Visual Studio 2010 are also the last versions to support Itanium.

- "Intel C++ Composer XE 2011 for Linux Installation Guide and Release Notes". Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- "Intel Reaffirms Commitment to Itanium". Newsroom.intel.com. March 23, 2011. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- McLaughlin, Kevin (March 28, 2011). "HP CEO Apotheker Slams Oracle For Quitting Itanium". Crn.com. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- Prickett, Timothy (April 14, 2011). "Huawei to forge big red Itanium iron". Theregister.co.uk. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- McMillan, Robert (February 1, 2012). "HP Paid Intel $690 Million To Keep Itanium On Life Support". wired.com. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- "SAP Product availability Matrix". SAPPAM web site. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- "Oracle Issues Statement" (Press release). Oracle Corporation. September 4, 2012. Archived from the original on March 8, 2013. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- "HP NonStop server update". Intel Corporation. November 5, 2013. Archived from the original on November 8, 2013. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- "HP's Xeon-based Superdome is another nail in Itanium's coffin". V3.co.uk. December 5, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

Other websites

- Intel Itanium Home Page

- HP Integrity Servers Home Page Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Intel Itanium Specifications

- Some undocumented Itanium 2 microarchitectural information Archived 2007-02-23 at the Wayback Machine

- IA-64 tutorial, including code examples at the Internet Archive

- Itanium Docs at HP

- Historical background for EPIC instruction set architectures