Immune system

The immune system is the set of tissues which work together to resist infections. The immune mechanisms help an organism identify a pathogen, and neutralize its threat.[1]

The immune system can detect and identify many different kinds of disease agents. Examples are viruses, bacteria and parasites. The immune system can detect a difference between the body's own healthy cells or tissues, and 'foreign' cells. Detecting an unhealthy intruder is complicated, because intruders can evolve and adapt so that the immune system will no longer detect them.

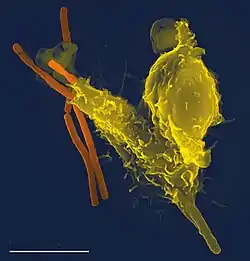

Once a foreign cell or protein is detected, the immune system creates antibodies to fight the intruders, and sends special cells ('phagocytes') to eat them up.

Innate immune system

Even simple unicellular organisms such as bacteria possess enzyme systems that protect against viral infections. Basic immune mechanisms appeared in ancient life forms and remain in their modern descendants, such as plants and insects. These mechanisms include antimicrobial peptides (called defensins), phagocytosis, and the complement system. These make up the innate immune system, which defends the host from infections in a non-specific way.[2] The simplest innate system is the cell wall or barrier on the outside to stop intruders getting in. For example, skin stops most outside bacteria getting in.

The response

The innate immune system responds very quickly to anything foreign that enters the body. When something gets past the skin, as through a cut, the immune cells work to find the intruder and to alert each other of the foreign object. Small immune cells bring other cells from all over the body to the site where the foreign object was found. Other immune cells can send out messengers to cells nearby to have them help attack the foreign object. This process can make the skin look red and feel hot. Phagocyte cells eat anything foreign that enters the body. This response is called non-specific because it responds the same way to anything foreign that enters the body from germs to a piece of dust.[3]

Adaptive immune system

Vertebrates, including humans, have much more sophisticated defense mechanisms. The innate immune system is found in all metazoa, but the adaptive immune system is only found in vertebrates.[4]

The adaptive immune response gives the vertebrate immune system the ability to recognize and remember specific pathogens. The system mounts stronger attacks each time the pathogen is encountered. It is adaptive, because the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges.

The typical vertebrate immune system consists of many types of proteins, cells, organs, and tissues that interact in a complex and ever-changing network. This acquired immunity creates a kind of "immunological memory".

The process of acquired immunity is the basis of vaccination. Primary response can take 2 days to 2 weeks to develop. After the body gains immunity towards a certain pathogen, if infection by that pathogen occurs again, the immune response is called the secondary response.

Autoimmune disorders

In some organisms, the immune system has its own problems within itself, called disorders. These result in other diseases, including autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases and possibly even cancer.[5][6] Immunodeficiency diseases occur when the immune system is less active than normal. Immunodeficiency can either be the result of a genetic (inherited) disease, or an infection, such as the acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), that is caused by the retrovirus HIV, or other causes.

In contrast, autoimmune diseases result from an immune system that attacks normal tissues as if they were foreign organisms. Common autoimmune diseases include Hashimoto's thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, Type 1 diabetes, and Lupus erythematosus.

Immunology is the study of all aspects of the immune system. It is very important to health and diseases.

History of immunology

Immunology is scientific part of medicine that studies the causes of immunity to disease. For many centuries people have noticed that those who recover from some infectious diseases do not get that illness a second time.[7]

In the 18th century, Pierre Louis Maupertuis made experiments with scorpion venom and saw that certain dogs and mice were immune to this venom.[8] This and other observations of acquired immunity led to Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) developing vaccination and the germ theory of disease.[9] Pasteur's theory was in direct opposition to contemporary theories of disease, such as the miasma theory. It was not until the proofs Robert Koch (1843–1910) published in 1891 (for which he was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1905) that microorganisms were confirmed as the cause of infectious disease.[10] Viruses were confirmed as human pathogens in 1901, when the yellow fever virus was discovered by Walter Reed (1851–1902).[11]

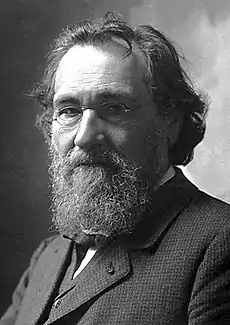

Immunology made a great advance towards the end of the 19th century, through rapid developments, in the study of humoral immunity[12] and cellular immunity.[13] Particularly important was the work of Paul Ehrlich (1854–1915), who proposed the side-chain theory to explain the specificity of the antigen-antibody reaction. The Nobel Prize for 1908 was jointly awarded to Ehrlich and the founder of cellular immunology, Ilya Mechnikov (1845–1916).[14]

Evolution

The immune system is extremely ancient. It may go back to single-celled eukaryotes which needed to distinguish between what was food and what was part of themselves.[15]

- "Genomic analysis of plants and animals provides evidence that a sophisticated mechanism of host defense was in existence by the time the ancestors of plants and animals diverged. This system, shared by plants and animals, is the Toll pathway of NFκB activation of gene function... The necessary DNA sequences are found in invertebrates, vertebrates, and plants".[15]

References

- Janeway C.A et al 2001. Basic concepts in immunology, Chapter 1 in Immunobiology, 5th ed, New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7

- Beck, Gregory; Gail S. Habicht (1996). "Immunity and the invertebrates" (PDF). Scientific American. 275 (5): 60–66. Bibcode:1996SciAm.275e..60B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1196-60. PMID 8875808. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- Kindt T.J; Goldsby R.A; Osborne B.A. & Kuby J. 2007. Chapter 1: Overview of the Immune System. In Kuby immunology (6th ed., pp. 1–22). essay, W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Janeway C.A. 2001. Evolution of the immune system. In Immunobiology ed Janeway et al. 5th ed, 597–607. New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7

- "Inflammatory cells and cancer", Lisa M. Coussens and Zena Werb 2001. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 193 F23-26.

- "Chronic immune activation and inflammation as the cause of malignancy" K.J. O'Byrne and A.G. Dalgleish 2010. British Journal of Cancer. 85, 473-483.

- Retief FP, Cilliers L (1998). "The epidemic of Athens, 430–426 BC". South African Medical Journal. 88 (1): 50–53. PMID 9539938.

- Ostoya P (1954). "Maupertuis et la biologie". Revue d'histoire des sciences et de leurs applications. 7 (1): 60–78. doi:10.3406/rhs.1954.3379.

- Plotkin SA (2005). "Vaccines: past, present and future". Nature Medicine. 11 (4 Suppl): S5–11. doi:10.1038/nm1209. PMC 7095920. PMID 15812490.

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1905, Nobelprize.org, accessed 8 January 2007

- Major Walter Reed, U.S. Army, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, accessed 8 January 2007.

- In humoral immunity, antibodies are secreted into bodily fluids such as blood and lymph.

- Mechnikov, Ilya; translated by F.G. Binnie (1905). Immunity in infective diseases (full text version: Google Books). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0548-64719-4.

- The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1908 Nobelprize.org, accessed 8 January 2007

- Janeway C.A et al 2001. Evolution of the immune system: past, present and future. 'Afterword' in Immunobiology, 5th ed, New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4101-7