Higgs field

The Higgs field is a field of energy that is thought to exist in every region of the universe. The field is accompanied by a fundamental particle known as the Higgs boson, which is used by the field to continuously interact with other particles, such as the electron. Particles that interact with the field are "given" mass and, in a similar fashion to an object passing through treacle (or molasses), will become slower as they pass through it. The result of a particle "gaining" mass from the field is the prevention of its ability to travel at the speed of light.

Mass itself is not generated by the Higgs field; the act of creating matter or energy from nothing would violate the laws of conservation. Mass is, however, gained by particles via their Higgs field interactions with the Higgs boson. Higgs bosons contain the relative mass in the form of energy and once the field has endowed a formerly massless particle, the particle in question will slow down as it has now become "heavy".

If the Higgs field did not exist, particles would not have the mass required to attract one another, and would float around freely at light speed.

Giving mass to an object is referred to as the Higgs effect. This effect adds mass to any particle that interacts with the field.

The Higgs effect

The Higgs effect was first theorized in 1964 by writers of the PRL symmetry breaking papers. In 1964, three teams wrote scientific papers which proposed related but different approaches to explain how mass could arise in local gauge theories.[1][2][3][4][5]

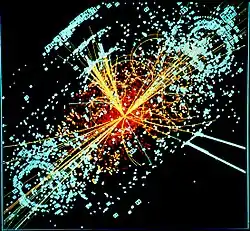

In 2017 the Higgs boson, and implicitly the Higgs effect, were tentatively proven at the Large Hadron Collider (and the Higgs boson was discovered on July 4, 2012). The effect was seen as finding a missing piece of the Standard Model.

According to gauge theory (the theory underlying the Standard Model), all force-carrying particles should be massless. However, the force-particles that mediate the weak force have mass. This is due to the Higgs effect, which breaks the SU(2) symmetry; (SU stands for special unitary, a type of matrix, and 2 refers to the size of the matrices involved).

A symmetry of a system is an operation done to a system, such as rotation or displacement, that leaves the system fundamentally unchanged. A symmetry also provides a rule for how something should always act unless acted on by an outside force. An example is a Rubik's Cube. If we take a Rubik's cube and scramble it by making whatever moves we want, it is still possible to solve it. Since each move we make still leaves the Rubik's cube solvable, we can say that these moves are 'symmetries' of the Rubik's cube. Together, they form what we call the symmetry group of the Rubik's cube. Making any of these moves doesn't change the puzzle, always leaving it solvable. But, we can break this symmetry by doing something like taking the cube apart, and putting it back together in a completely wrong way. No matter what moves we try now, it is not possible to solve the cube. Breaking the cube apart and putting it back together in the wrong way is the 'outside force'. Without this outside force, nothing we do to the cube makes it unsolvable. The symmetry of the Rubik's cube is that it stays solvable whatever moves we make, as long as we do not take apart the cube.

Creation of Higgs boson

The way that the SU(2) symmetry is broken is known as "spontaneous symmetry breaking". Spontaneous means random or unexpected, symmetries are the rules that are being changed, and breaking refers to the fact that the symmetries are no longer the same. The result of spontaneously breaking the SU(2) symmetry can be a Higgs boson.

Reason for Higgs effect

The Higgs effect occurs because nature "tends" towards the lowest energy state. The Higgs effect will happen because gauge bosons near a Higgs field will want to be in their lowest energy states, and this would break at least one symmetry.

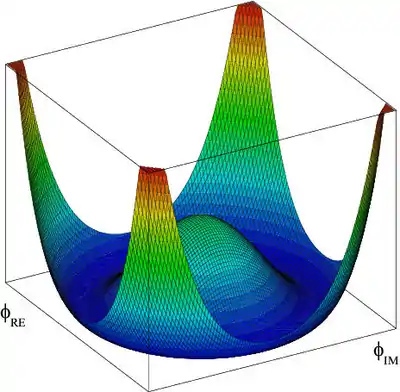

To justify giving mass to a would-be massless particle, scientists were forced to do something out of the ordinary. They assumed that vacuums (empty space) actually had energy, and that way, if a particle that we think of as massless were to enter it, the energy from the vacuum would be transferred into that particle, giving it mass. A mathematician named Jeffrey Goldstone proved that if you violate a symmetry (for example, a symmetry with a Rubik's cube would be if you state that the corners must always be rotated 0 or 3 times to be solvable (it works)), a reaction will occur. In the case of the Rubik's cube, the cube will become unsolvable if violated. In the case of the Higgs field, something named after Jeffrey Goldstone (and another scientist who worked with him named Yoichiro Nambu) is produced, a Nambu-Goldstone boson. This is an excited or energetic form of the vacuum, which can be graphed revealing that shown above. This was first explained by Peter Higgs.

References

- Englert, François; Brout, Robert 1964. Broken symmetry and the mass of gauge vector mesons. Physical Review Letters 13 (9): 321–23.

- Brout, R.; Englert, F. (1998). "Spontaneous symmetry breaking in gauge theories: a historical survey". arXiv:hep-th/9802142.

- Higgs, Peter 1964. Broken symmetries and the masses of gauge bosons. Physical Review Letters 13 (16): 508–509.

- Guralnik, Gerald; Hagen C.R. & Kibble T.W.B. 1964. Global conservation laws and massless particles. Physical Review Letters 13 (20): 585–587.

- G.S. Guralnik 2009. The history of the Guralnik, Hagen and Kibble development of the theory of spontaneous symmetry breaking and gauge articles. International Journal of Modern Physics A 24 (14): 2601–2627.